Mission Possible

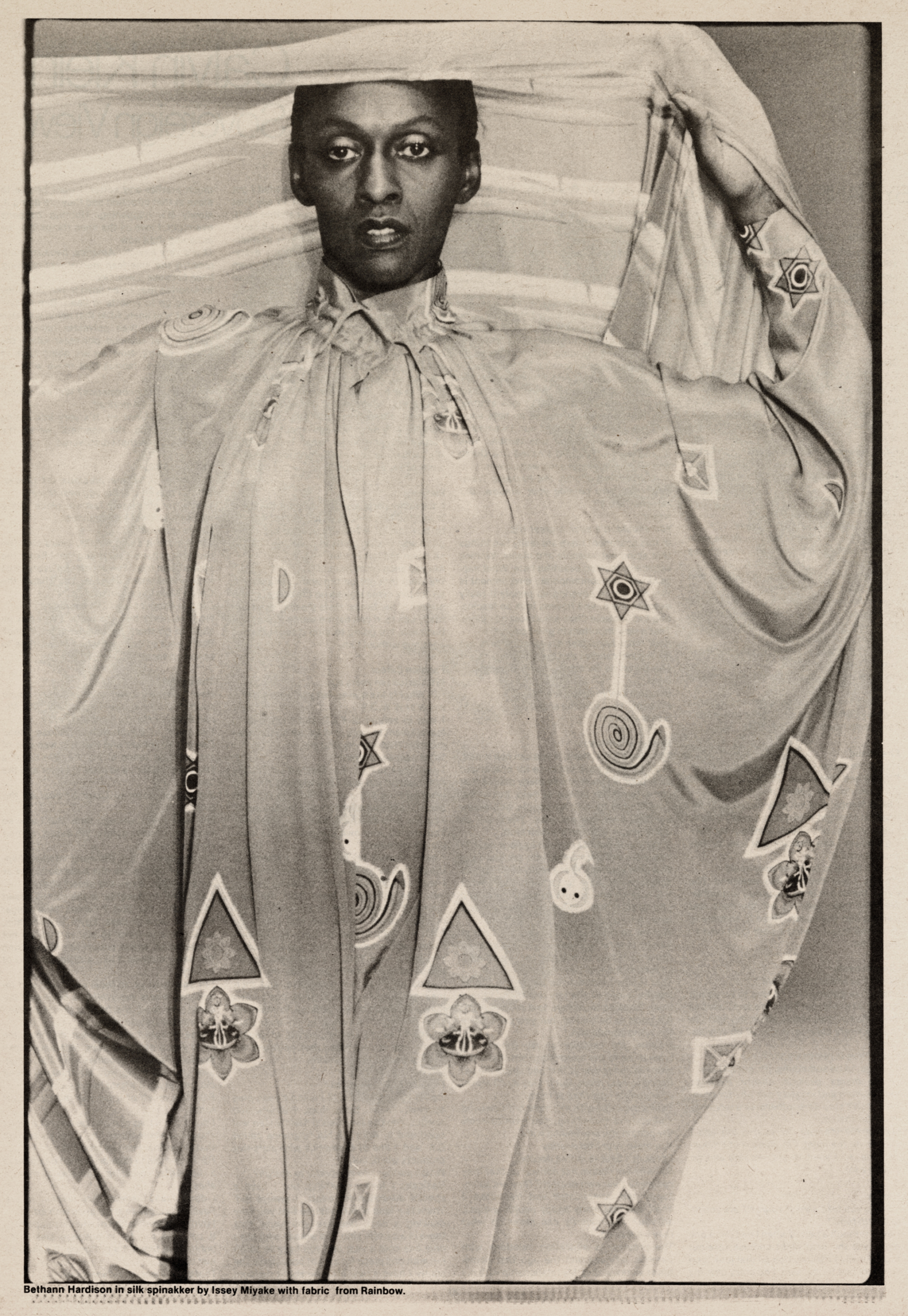

Bethann Hardison Tells Zendaya Why Her Mission Is Far From Over

In March of last year, Bethann Hardison sat front row at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées in Paris for the unveiling of Zendaya’s collaboration with the fashion designer Tommy Hilfiger. The 23-year-old actor had invited 59 women of color, among them Pat Cleveland, Beverly Johnson, and Grace Jones, to model the clothes. And while Hardison didn’t appear in the show, her presence in it was felt. Hardison helped transform American fashion in the late 1960s and ’70s, when she went from working at a button factory in New York’s Garment District to becoming an international model, after being discovered by the sportswear designer Willi Smith. The feather in Hardison’s fashion cap came in 1973 with her unforgettable appearance, alongside nine other Black models, at the historic Battle of Versailles, a face-off between American and French designers to raise money for the restoration of the palace. Hardison didn’t walk the runway so much as dance across it.

By the time her modeling career came to an end, Hardison was hard at work implementing the change she preached, first as a booking agent, then as a founder of her own agency. In 1988, she founded the Black Girls Coalition, a platform that gives voice to Black models, with her friend, the supermodel Iman. In the years since, she has become an industry oracle, guiding careers, amplifying voices, consulting for institutions that include Gucci and the CFDA, and racking up too many lifetime achievement awards to list. She recently reconnected with Zendaya from her home in upstate New York to discuss why her mission is far from over.

———

ZENDAYA: Hello, Miss Bethann.

BETHANN HARDISON: Hello, my sweetie pie.

ZENDAYA: How are you?

HARDISON: I’ve been really well, in the sense that I’ve been in upstate New York since March. Iman is not too far from here. She and I came up here together, and she hasn’t left at all.

ZENDAYA: What were you working on before this all happened?

HARDISON: I was traveling so much. I went to Anguilla, then I was home for a couple of weeks, and then I went to Egypt and sailed down the Nile. Then I went out to Los Angeles for Oscars week, and then to Italy right before the virus hit. Then I went to Chicago for Duro Olowu’s brilliant opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art. At that point, I had already been wearing masks and wiping down every surface for weeks. I’d been watching what was going on in China. Then I was supposed to be at the opening of the Willi Smith exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt museum in New York. What wound up happening is that COVID-19 hit and all the museums had to be shut down the day before the public opening. Iman and I saw it anyway, just without the public. Two days later, we came upstate.

ZENDAYA: You’re so busy. You’ve been going like this since you started modeling. I not only admire that, but I aspire to that. I want to be able to move the needle forward in the ways that you have.

HARDISON: I just want to make a change. For the last two years, I’ve been focused on young designers of color, trying to help those younger brands to have stronger businesses. I don’t care if they become famous or not, as long as they can leave their business to their children. I’m so sick of people saying, “Where are the Black designers?” It’s important to know that they definitely exist. They may not be as famous as Virgil Abloh, but everyone doesn’t have to have that journey.

ZENDAYA: A lot of people must come to you for guidance in that respect, because you know this industry so well.

HARDISON: What I’ve noticed since George Floyd’s death is that the movement against racial injustice is spilling over into the fashion industry, and people are really being able to speak up. I keep reminding people that the fashion industry is a tiny island. How many people can really fit onto it? It’s a tough business.

ZENDAYA: How have you seen the industry change over the years, and what still needs to be done?

HARDISON: The designer always had his own team. He was the one who selected the models. He and his team were the ones who determined who would be presenting the collection. And because of their excitement about a girl, they created a muse. Then, over the last 10 or 15 years, we started to have outside people come in. They became casting directors for the designers and stylists, so they determined who was going to be a model. Then Eastern Europe opened up, and they scouted there. All of a sudden, the supermodel, the glamorous girl, the girl of color—she got replaced by the Eastern European model. It was Miuccia Prada who started it, and then all the other designers followed. So the girl of color got eliminated, just like Linda Evangelista would have gotten eliminated. To see how we lost that rhythm was important in getting it back, because it looked like the industry had no clue about its own history. It was important for me to remind people that in their actions, whether there’s the intention or not, if you continue to use one model or no model of color, consistently for two or three seasons, that’s racist. I think it’s more about ignorance than it is the consciousness of racism. Now that we’ve had this pandemic, that’s leveled the playing field. Everybody has been affected, whether it be a very small brand or a very big luxury one. It’s going to be interesting to see what happens, because what we were facing before the pandemic was trying to get employment for people of color behind the scenes, whether it be in magazines, on sets, or on glam teams. And I believe there will be change. I’ve seen many marches, I’ve been around, and we always had white people who participated, but never like this. We’re definitely going to come away with something.

ZENDAYA: I sure hope so.

HARDISON: We as creators can make change, but the bigger problem is the political administration that we now sit with.

ZENDAYA: I think that a lot of it, too, for me, is that at the end of the day, I’m just an actress. I love what I do, but I’m not an organizer and I don’t do the groundwork. It’s about understanding your place and deferring to people who have a deeper understanding.

HARDISON: But that’s your activism: admitting what you don’t know and making room for those who do know. I’m always going around correcting the fact that everyone refers to me as an activist. There are moments when I’ve had to be an activist, but an activist has to remain active. Oftentimes, once I see that I’ve got the world where I want it to be, I lean back. I’m always an advocate, but activism? That’s a career.

ZENDAYA: Absolutely.

HARDISON: I love that you said, “I’m just an actress.” You want to stay in your lane, but also be clear about how you can help. That’s how I feel, too.

ZENDAYA: It’s one thing to see change, but to be a part of it is a whole other thing.

HARDISON: Very true. Every step I took, I was nervous going in. Nothing I ever did was done with great confidence. But you know your destiny. I went up against the international industry of fashion because I knew I could make a difference. I was sure of that. But some things, as I went along in life, I didn’t know. I was just hoping.

ZENDAYA: A lot of the young models coming up now, specifically young Black models, really look up to you, and I know you continue to have relationships with them and mentor them. When we did our show [Tommy Hilfiger’s TommyNow presentation in September 2019], you came backstage and you gave the girls a talk. I’m not a model, but in my industry, it’s been more difficult being able to find mentors, people who are willing to reach out to you and give you knowledge. And from what I know, modeling is definitely a tough industry.

HARDISON: Mentors in any industry are rare birds. They’re not the norm. I really do have a kinship with the girls because they don’t know the history I know. When I started the Black Girls Coalition, it was like I was celebrating them. People think we started it because we were talking about racism. That wasn’t how it started. It started because I wanted to celebrate these girls who were working in editorial. We were runway models, and then eventually we got eliminated because Calvin Klein started booking the print girls to do the runway. It changed everything. Even as a model agency owner, I had to say no to certain girls I liked because I knew I didn’t have the market to be able to sell everybody. But I want to celebrate them and let them see each other and work together, because women don’t always work well together. Then you think about models—“Oh my god, you’re going to have them together? And they’re all brown?” There’s competition in that.

ZENDAYA: We’ve talked about that as well, the concept that within our communities, there’s always only space for one.

HARDISON: Yeah.

ZENDAYA: It’s heartbreaking. There should be room for more than one. We should be able to open the door and let there be a flood. The idea that there can only be one at a time breeds hurt and pain and competition. What else do you want to do?

HARDISON: My documentary [Invisible Beauty] has been dormant for about six or seven years, but now, we’ve picked it back up. The film is really about me. Before, it was about the industry. I was just exposing what was going on, the lack of diversity. But now the film tells my story. And then there’s my book. I’m going to do it, because I know how to wrap my mind around it now. And I’m happy to be working with Gucci. I knew the old Gucci family back in the day, the gangster ones. So I like [Gucci’s creative director] Alessandro Michele and [Gucci’s CEO] Marco Bizzarri. They’re very forward-thinking. Everybody else is going to Florida to retire, but I would never. Here I am, still being asked to do things, and I’d happily do things with people who are trying to help make change. I really do appreciate that. That’s my personality. I don’t need a lot of sleep and I don’t need a lot of fluid. I just need enough fuel to keep the body going.

ZENDAYA: That sounds like a good plan. Fuel the body and keep going.

HARDISON: Forward.

———

Photography Assistant: Sam Waxman