Andrew Richardson Shows His Softer Side

In 1998 Andrew Richardson launched the now infamous Richardson magazine—a radical publication about sex, fetish, desire, and porn stars. Speaking about sex in an analytical and academic way, Richardson is more an anthropology experiment than a titillating porn rag. In the new issue, A6, the magazine takes on its most challenging theme to date: Love.

The cover of A6 sees the skin-headed porn star Belladonna smiling her signature gap-toothed smile, shot by Terry Richardson. Previous issues, which dealt with themes including feminism and the male gaze, have featured greats like Harmony Korine, Steven Klein, Mario Sorrenti, and Bruce LaBruce, offering their take on extreme sex for Richardson‘s beautifully printed pages. And though there have only been six issues in its 14-year lifespan, the magazine’s transgressive, punk ideals have turned Andrew Richardson into something of a counterculture icon.

Born in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, the dashing Mr. Richardson has lived in New York for over 20 years and works primarily as a fashion stylist. (Fun fact: he worked on Madonna’s Sex book back in ’92.) The latest issue of his sex mag features an investigation into the BDSM empire Kink.com, a photo essay by Dan Colen about his friendship with Dash Snow, writings on love by Dennis Cooper and drawings by the Chapman Brothers, to name a few.

Interview talks with him about love, sex, and the makings of what he has called America’s first “asexual sex magazine.”

KARLEY SCIORTINO: Why love?

ANDREW RICHARDSON: I thought it was the most difficult subject we could deal with. We made associations to fraternal love, love of and a loss of love, or one could say atypical concepts of love. It turned out more counter-love, in a way.

SCIORTINO: Do you believe in love?

RICHARDSON: Well, I don’t really know what love is. There are many languages that use multiple words to describe love, in order to capture the nuances of the feeling. But we good Anglo-Saxons just have one blanket term for the emotional reaction to intimacy. A friend of mine once told me that his parents, who are still together and have a very good relationship, never use the word, and I think it’s probably a good idea. I think if you don’t say it and instead just behave in a loving, considerate, respectful way towards the person you’re with, that it’s much better than saying “I love you” to compensation for less than excellent behavior.

SCIORTINO: And when people say “I love you,” too often it loses its meaning and becomes cringey.

RICHARDSON: Yeah. I’ve been in situations where I’ve felt extremely euphoric—those moments when you just want to cut yourself open and become one with the other person. And when you feel that way using the word “love” can feed the high. But demonstrative love is the worst thing in the world.

SCIORTINO: In this issue, you published excerpts from Dennis Cooper’s novels and poems that pertain to love. Often, his depictions of love and obsession are similar to what you just described—wanting to cut someone open and crawl inside their body, to get at what’s “inside” a person. It’s a good analogy.

RICHARDSON: I was watching an interview with a porn star recently who had done lots of extreme scenes, and the interviewer asked her, “Now that porn has reached such an extreme level, what’s next?” And she said, “Maybe people will start cutting each other open and fucking the wounds.” Now that would be impractical, but I get it.

SCIORTINO: Do you think that’s what Bruce LaBruce was getting at with all his zombie porn?

RICHARDSON: Yeah, but Bruce is so smart that when he does something like that you think, “Oh, I’ve figured it out,” but then some much deeper, significant reason is revealed to you that makes you realize just how superficial you are.

SCIORTINO: David Foster Wallace wrote a famous essay about the porn industry after attending the 1997 AVN Awards. One of his conclusions was that all of the clichés about porn are true, and that the people involved are quite stupid. Do you think that’s accurate?

RICHARDSON: Well, that conclusion is a bit easy, isn’t it? In my experience, people in the porn business have often surprised me by being smarter, more ambitious, or more in control of their careers and lives than one would presume. And maybe going to the AVN Awards isn’t the best place to get an idea of who the people in porn are. That’s like going to the Oscars and seeing a drunk actress make a fool of herself, and then thinking all actresses are drunken fools. It’s difficult to write about porn, because it’s something that’s quite sensational and quite loaded. When our magazine interviews porn stars, our aim isn’t to be mean, or to expose them for being clichés. We just show them for who they are.

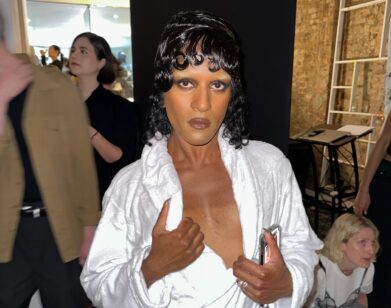

SCIORTINO: Why did you choose porn star Belladonna for the cover of this issue?

RICHARDSON: People in the office had been talking about her for ages and it just seemed like the right thing to do. I would have put her on the cover had we not taken a hiatus from publishing the magazine in 2003—she would have followed Tera Patrick—but that didn’t happen. I think it’s interesting that her success was an accident of fate. About ten years ago, Diane Sawyer interviewed Belladonna for Prime Time, they followed her around for two years, and in her final interview she broke out in tears, and did all the things that porn stars are supposed to do—she gave the sensational interview. And the show gave her so much exposure that she became a huge success.

SCIORTINO: It humanized her.

RICHARDSON: Yeah, it showed her to be vulnerable and conflicted, and maybe that was an unconscious turn on for a lot of people. And by doing that she changed the perception of what a porn star is—within the industry and outside of it—on its head. Really she was the right girl, right place, right time.

SCIORTINO: You interview porn stars in the way a culture magazine would interview an actress. What was the idea behind this?

RICHARDSON: When I came to New York in 1989, I started listening to Howard Stern. Porn wasn’t readily available; to get it, you had to go to some dodgy store and have a shame attack walking in and out. It felt a bit dangerous, like scoring drugs or something. And so I knew about porn stars mainly from listening to Howard Stern. What we do with our cover girls is an extension of, or a recontextualizing of, the Howard Stern interview. Except where Stern asks very puerile questions and can be a bit juvenile, we deal with it more analytically. We’re trying to find out who these women are, but without being flippant or crude about it.

SCIORTINO: Is it correct to say that Richardson deals with the psychology behind the people who are involved in porn and the sex industry?

RICHARDSON: That’s one aspect. People often call it a porn magazine, but outside of the cover star I don’t think the magazine really deals with the porn industry. We deal more with people like Annie Sprinkle, who come from the world of porn but have radicalized it.

SCIORTINO: Because you have been exposed to so many different avenues of sexual behavior through the magazine, has it changed the way you think about sex, or affected what you are into personally?

RICHARDSON: It’s definitely informed me about what’s potentially on the menu. When you enter this somewhat isolated world, stuff that would be shocking to civilians becomes no longer a big deal. You realize it’s all “just fucking.” But I think a lot of the change that’s happened within me is more to do with the way people’s perceptions and expectations of me are different, now that I’m publicly known for making a sex magazine.

SCIORTINO: So basically now people think of you as a sophisticated bachelor who fucks lots of porn stars.

RICHARDSON: Yeah, like a low-rent James Bond, I suppose. But I’m probably a lot more sensitive than people imagine.

SCIORTINO: You have lots of feelings.

RICHARDSON: When I’m not compartmentalizing them, yeah. But I enjoy that confusion, because I’m into provocation. At heart, the magazine is really about provocation and confrontation; sex is just what we use to provoke. Because if you pontificate about sex in a fanatical way, you’re a joke. But if you’re analytical about sex, it makes people very uncomfortable.

SCIORTINO: Are you trying to piss people off?

RICHARDSON: Well, I think when you are a provocative person, you need a negative reaction, or you need to be misunderstood, in order to then come back in quite an articulate way and explain just how wrong the other person is. Most of the work that I enjoy from people, whether it’s film, painting, photography, or writing, is fueled by anger more than it’s fueled by love, or a desire to share. Deep down I’m just a middle-class boy from suburban England, so part of me is very conservative. So in a way I’m seeing how far I can push myself, or the audience, to a point where I don’t go to jail, but I push some buttons. It’s the erotic attack. I’m trying to shock my parents, ultimately.

SCIORTINO: So what was your introduction to sex, being a suburban British child with parents in the Church of England?

RICHARDSON: It was from a Harold Robbins book, when I was about 16. I had seen porn before—I’d looked at some porn magazine under a bush at school or whatever—but that book was my first real introduction to sensational descriptions of fantastical sex. Like Helmut Newton sex.

SCIORTINO: One of the main stories in this issue is about your trip to the Kink.com armory in San Francisco. Can you tell us about that?

RICHARDSON: The story is about extreme sex practices, and the modern evolution of porn and fetish. I am interested in how extreme sex is commercialized in the online world, and how fetish is the only thing in porn that’s really growing right now, whereas the more conventional idea of pornography is sort of dying.

SCIORTINO: Fetish is so mainstream now.

RICHARDSON: It is. I worked as an assistant on Madonna’s Sex Book in 1992, and at the time that was pretty radical, now everybody knows about bondage and fetish. It’s in fashion; a lot of what is edgy about fashion comes from the fetish community.

SCIORTINO: So in a world where extreme sex is becoming more and more commercialized, does Richardson need to make extreme changes in order to keep being transgressive?

RICHARDSON: It’s like religion in a way: religions shouldn’t change. They should be what they are, and when they’re out of date they should stop being. Richardson is what it is, there’s a rough formula to it, and when that’s no longer relevant I’ll stop making it and start doing something else.