Anthony Hopkins Talks to Brad Pitt About Movies, Mortality, and Mistakes

Coat by Gucci. Shirt and Sunglasses by Prada. Jeans (worn throughout) Anthony’s own. Belt (worn throughout) by Tod’s.

After well over a hundred starring roles, in a career stretching back to the 1960s, it’s a wonder Hollywood hasn’t run out of meaty, memorable archetypes for Sir Anthony Hopkins to portray. In the past, the 81-year-old Welsh Oscar winner has played more than his share of deviously brilliant psychotic murderers (The Silence of the Lambs and its sequels, Fracture); restrained, restricted Englishmen on the brink of emotional crises (Howards End, The Remains of the Day, Shadowlands, You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger); iconic artistic geniuses who defined the 20th century (Surviving Picasso, Hitchcock); and more Shakespeare characters than should be expected of anyone (Hamlet, King Lear, Titus). Not to mention the other gods of celluloid he has traded dialogue with over the years (his third movie role had him starring opposite Katharine Hepburn and Peter O’Toole in 1968’s The Lion in Winter).

Many actors would have run out of passion or punch after six decades in front of the camera. But not Hopkins, with his signature heat-seeking blue-eyed stare, slicked-back hair, and surgical yet lilting voice. His endurance may have something to do with the fact that while he looms so large on the big screen, he’s largely kept his private life private (although he has racked up more than a million followers on his cheeky Instagram account). Or maybe it has to do with learning the profession on the London stage; Hopkins has a solemn thespian’s presence and a nobility in delivery that raises the level of any material. Or maybe it’s just that Hopkins doesn’t know how to turn down a great part. The actor might have outdone himself with his latest, playing the controversial Pope Benedict XVI, who led 1.2 billion followers of the Catholic Church from 2005 to 2013 (this isn’t the first time Hopkins has played a priest, either). In Fernando Meirelles’s world-religion drama The Two Popes, which screened at the Toronto Film Festival in September, the Bavarian hardline-conservative at the top of the church goes toe-to-toe with the compassionate reformist Jesuit who will eventually supplant him (the future Pope Francis played with tremendous empathy by Jonathan Pryce). What could have been a cold, frigid, unbending character study becomes, in Hopkins’s hands, a testament to a kind of humbling and loss of self-direction. The actor spends the majority of the film dressed in white robes, a white skullcap, blood-red shoes, a gold cross, and a digital watch like a Fitbit counting his daily walking steps around the Vatican. The result is a compassionate portrait of a powerful leader lost to his age, in need of “a spiritual hearing aid” to guide his flock. And yet, the audience can’t help liking the very fallible human buried in the gilded cassock.

Hopkins first worked with Brad Pitt in 1994’s western epic Legends of the Fall. They reunited for 1998’s fantasy drama Meet Joe Black. This past October, the two veteran actors met up at a hotel in Beverly Hills to discuss, among other things, the beauty of embracing our mistakes

———

BRAD PITT: Do you believe in fate? And I don’t mean in destiny or greatness. I just mean that things are fated.

ANTHONY HOPKINS: Yes, I do.

PITT: I’ve come to believe this in the last few years. How do you describe it?

HOPKINS: I’ve been dreaming of elephants. I don’t know why. There was a film I saw, when I was a child, called Elephant Boy. The elephant would take Sabu, the main character, through the jungle, and I remember sitting there with my grandfather watching it. My impression is that I sat on this big beast, whatever it is—life. At some point, I made an unconscious choice to sit on this beautiful, powerful thing. And I just go where it takes me. I think that what happens to people like you and myself. We don’t even know why. Maybe it’s a desire to escape from something. But what I believe now is that we can’t take credit or blame.

PITT: I feel the same. Certainly the credit. The blame I’m still wrestling with.

HOPKINS: What’s the blame?

PITT: I’m realizing, as a real act of forgiveness for myself for all the choices that I’ve made that I’m not proud of, that I value those missteps, because they led to some wisdom, which led to something else. You can’t have one without the other. I see it as something I’m just now getting my arms around at this time in my life. But I certainly don’t feel like I can take credit for any of it.

HOPKINS: I’ve read you had a struggle with booze and all that.

PITT: Well, I just saw it as a disservice to myself, as an escape.

HOPKINS: It was necessary.

PITT: To some degree, yes.

HOPKINS: It’s a gift. I myself needed to hide it, years ago.

PITT: I remember on Meet Joe Black, you were talking about it. You had dumped it.

HOPKINS: Forty-five years, almost. But I’m not an evangelist about it.

PITT: Nor I.

HOPKINS: But I look at it, and I think, “What a great blessing that was, because it was painful.” I did some bad things. But it was all for a reason, in a way. And it’s strange to look back and think, “God, I did all those things?” But it’s like there’s an inner voice that says, “It’s over. Done. Move on.”

PITT: So you’re embracing all your mistakes. You’re saying, “Let’s be our foibles, our embarrassment. There’s beauty in that.”

HOPKINS: It’s great.

PITT: I agree. I’m seeing that these days. I think we’re living in a time where we’re extremely judgmental and quick to treat people as disposable. We’ve always placed great importance on the mistake. But the next move, what you do after the mistake, is what really defines a person. We’re all going to make mistakes. But what is that next step? We don’t, as a culture, seem to stick around to see what that person’s next step is. And that’s the part I find so much more invigorating and interesting.

HOPKINS: We’ve all screwed up.

Coat and Shirt by Prada.

PITT: “Fuck it.” That was one of the first things I heard you say, back during Legends of the Fall when I was just getting my opportunity. And it always stuck with me. It seems to be a theme, a guiding principle. “Fuck it.”

HOPKINS: I once asked a Jesuit priest, “What is the shortest prayer in the world?” He said,“Fuck it.” It’s the prayer of release. Just say, “Fuck it.” None of it is important. The important thing is to enjoy life as it is. Your life today, it’s fantastic.

PITT: It’s all relative, isn’t it?

HOPKINS: I’ve had such a ball in my life, and I can’t believe I’m here.

PITT: You’re as ferocious as ever. You feel as strong as ever. You’re as vibrant as ever.

HOPKINS: And you’re as easy going as ever.

PITT: Pretty much, it’s my gliding speed. But I lose it at times. I get sucked into something, and I can lose it. I take my hands off the wheel.

HOPKINS: You’re human.

PITT: I’m human. I have the privilege of sometimes getting to hangout with Frank Gehry. He just turned 90 this last year and is as creative as ever, creating some of the great buildings of our time. And it makes me think, “We’re human, we want purpose, we want meaning in our lives.” But to attain that, the key is two things: staying creative and being with the people we love.

HOPKINS: That’s it. I’m so honored that you’re doing this, because you have this natural power of life in you. On Meet Joe Black, you were very quiet and you didn’t cause any trouble. I was the troublemaker on that set.

PITT: I was actually going through a difficult time during that film. I felt pretty shackled. I didn’t feel very free.

HOPKINS: You didn’t?

PITT: Not at all. With Legends I did. I felt pretty good out there. So what was it about The Two Popes? It’s fascinating. Watching you and Jonathan Pryce was like watching Djokovic and Federer in the finals. They’re amazing scenes. It felt pretty special, what you guys were doing.

HOPKINS: Well, it was. I didn’t know Jonathan before. We had such a laugh, because he was number one on the call sheet, and I’d say, “But I’m a Sir.”

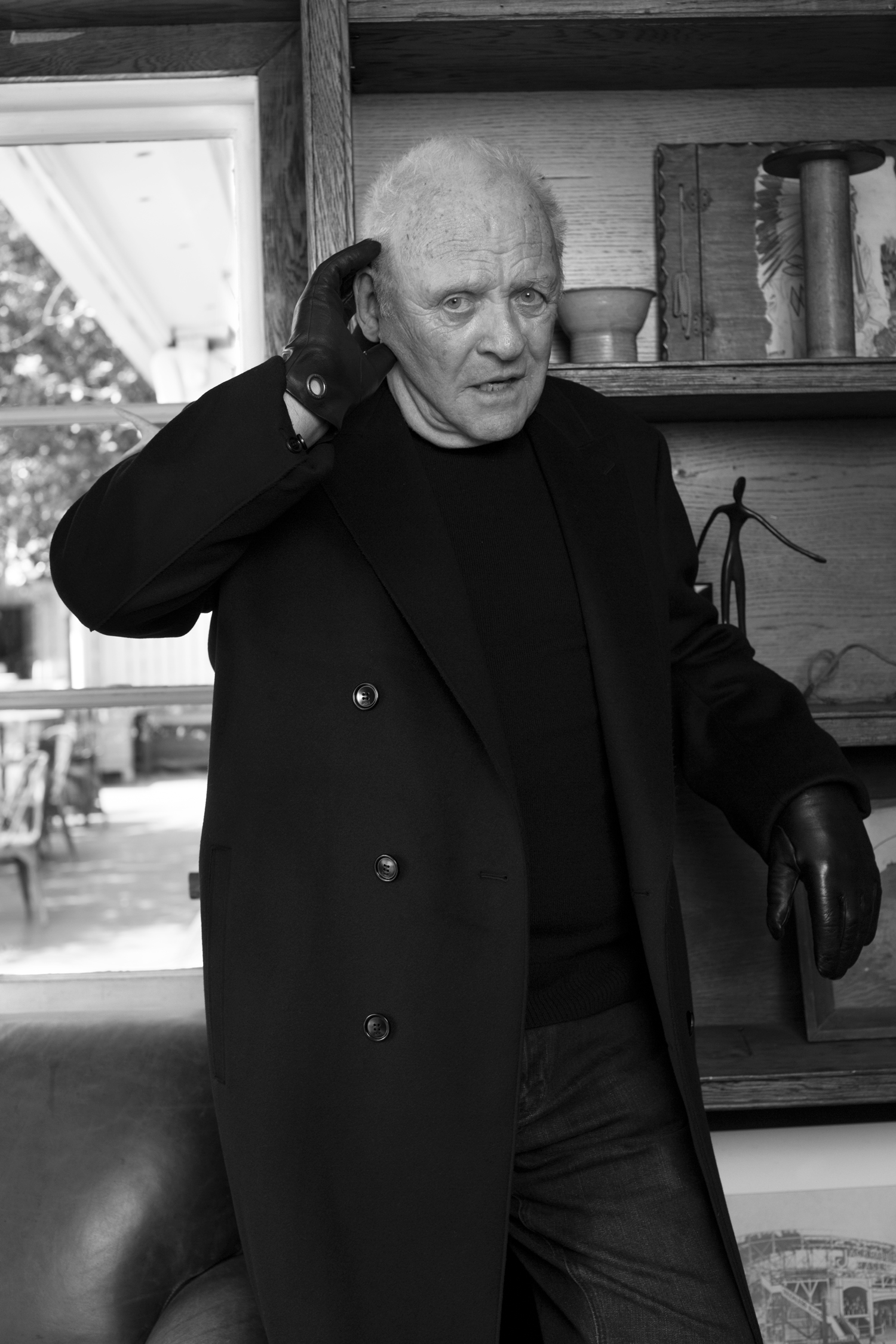

Coat and Sweater by Dior Men. Gloves by Balenciaga.

PITT: [Laughs] That’s great.

HOPKINS: My agent phoned, and he said, “The Pope.” And I said, “Okay.” I did a bit of research—not research, but I tried to figure out the truth of it all, without going in too deep. I arrived in Rome, and it’s like John Wayne said. Spend one year in Monument Valley and you don’t have to act.

PITT: There are some longer scenes, which I still adore, but which don’t seem as palatable anymore in the cinema experience. I understand that The Two Popes will come out in theaters, and then on Netflix. I really like that we have these streaming services, because I’m seeing gutsy material. I’m seeing material that studios aren’t able to gamble on. Through streaming services, artists are the ones who are able to gamble. I feel like cinema is being reduced more and more to spectacle, something more sensational. I don’t mean that as a negative, but I’m seeing more thought-provoking pieces like The Two Popes being done, and I’m pretty grateful for it.

HOPKINS: It’s wonderful. I watched The Tree of Life again, and then I went back into The Thin Red Line [also directed by Terrence Malick], on streaming. I’ve watched some amazing series, British things, episodical things.

PITT: Killing Eve was good.

HOPKINS: Have you seen Happy Valley?

PITT: I haven’t.

HOPKINS: I’m not a great fan of going to movies anymore. Except, for example, I went to see Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood. I’m not great at going to see the green screen films. I’ve been in a few of them and they’re fun, but they don’t grab me. I’m a bit too old for that.

PITT: It’s exactly that. It’s fun.

HOPKINS: People ask me questions about present situations in life, and I say, “I don’t know, I’m just an actor. I don’t have any opinions. Actors are pretty stupid. My opinion is not worth anything. There’s no controversy for me, so don’t engage me in it, because I’m not going to participate.”

PITT: I feel the same. I don’t care. I’m glad things are always evolving and changing, and complaining about it won’t do any good. You work with what you have. Like digital, they’re doing amazing things with it, so I don’t lament that film is being used less and less. What about the responsibility you feel when playing a real-life character? There’s no way to get the actual life, beat-by-beat, of a person, but you aim for an essence, correct?

HOPKINS: Oliver Stone gave me the part of Nixon, and I remember thinking, “Why would he give me that part?” And he said, “Because I’ve read interviews about you being a loner. That was Nixon.” So I watched a lot of Nixon films. I went down to Yorba Linda, California, to see the house where he was born. Bill Clinton told me that when he became president, he would phone Nixon every week.

PITT: Really?

HOPKINS: He’d ask him about China and Russia. Clinton said this of him: He was a brilliant politician, but there was something in him that was so insecure. And Oliver just tried to portray the man as he was—neither good or bad, but a man who makes mistakes, as we all do. I found it very emotional to play him, because I could feel what it must have been like, the disgrace of having to resign. And then the humiliation of having to say goodbye.

PITT: Getting on the helicopter.

HOPKINS: And then I read about his wife. She couldn’t bear to look down at the lawn of the White House as they took off.

PITT: It’s a fascinating story from a humanistic point of view. The indelible moment for me was when he—you—have the moment of, “Why don’t they like me?”

HOPKINS: That’s it. You can see the pain in him, and you think, “Well, am I better than him? No. I’m not better than him. I’ve got my own immoral quirks.”

PITT: In some way, it comes back to fate.

HOPKINS: Yes. Why do we do the things we do? We have no idea. I don’t know why I drank all my life. I did it because it was the only thing I knew. I look back now and I think, “Well, it wasn’t bad, but I don’t want to do it again.” I caused a bit of damage then, but I’ve made my apologies to people for doing what I did. It’s all part of being alive. And whatever power there is in us, it’s forgiving. It’s over. Forget it. Just move on.

PITT: I find that beautiful. And it makes me think of how prone we are to want to see things in black and white, and not really investigate the grays.

HOPKINS: There’s a wonderful Marlon Brando documentary, and there’s one scene of him with his father. He’s the greatest actor ever, but his father never even gave him acknowledgement. There’s a shot of his father, sitting down next to his son, and Mike Wallace asks, “So, what do you think of your son’s success?” And his father says, “Yeah, it’s okay.” And you see the hurt in Brando. I cried. The thing about me is, I cry at the drop of a hat, because everything moves me, because I’m getting old. Inside, we get the wallpaper stripped off all of our defenses, bit by bit, clawed away. Do you cry often?

PITT: I am quite famously a not-crier. Is that a term? I hadn’t cried in, like, 20 years, and now I find myself, at this latter stage, much more moved—moved by my kids, moved by friends, moved by the news. Just moved. I think it’s a good sign. I don’t know where it’s going, but I think it’s a good sign.

HOPKINS: You’ll find, as you get older, that you just want to weep.

PITT: Really?

HOPKINS: Yes. It’s not even about grief. It’s about the glory of life.

PITT: I see as much joy in your face as on the day I met you, if not more. I’ve been playing with sculpture in a sculpting studio the last few years, and our mutual friend said you’ve been painting like a banshee. What is it about that? To me, it’s another form of creating, but why is it meaningful to you?

HOPKINS: It’s meaningful to me because it keeps me out of trouble. It keeps me off the streets. Before Stella and I got married, she found scripts of mine with drawings in them. She said, “I want you to do some pictures for the wedding, a party gift.” I said, “I can’t.” She said, “Well, what are these? Just do them.” She had them framed and given out. And then she said, “Right, now I want you to start painting.” I said, “I can’t paint.” She said, “Will they put you in jail? Paint.” So I got a studio with canvases and I started painting, and I started selling them. And in the studio, in Malibu, I had some paintings hung up there, by the pool, and Stan Winston, who was a bonafide artist, came over for a barbecue, and he came into the studio to have a pee. I happened to be in there, and he said, “Who did all these?” I said, “I did.” He said, “Why are you pulling your face like that?” I said, “Well, I have no training.” He said, “Don’t take one lesson. You’ve got it. You’re an artist. You can paint. I couldn’t do that because I’m an academic painter, but you’re free.”

PITT: Isn’t it exciting when you realize that there’s so much to be discovered, and new things that you love doing?

HOPKINS: People say, “What’s your vision?” I say, “I don’t have any vision. I go in, look at the canvas, and just plop paint on it.”

PITT: How long can you lose yourself in there?

HOPKINS: All day.

PITT: I find that some days in the studio are arduous and lonely and monotonous, and other days I find it sensuous and beautiful—things are flowing, and it’s sublime.

HOPKINS: Beautiful, isn’t it?

PITT: As actors, what we do is a team sport. Making a film takes everyone. And we contribute what we contribute. Sometimes it’s going to be better than what we gave on the day. Sometimes it’s weaker than what we gave on the day. But it’s a team effort. I was really struck by this longing, this need to do something autonomous. I feel like it’s spiritual.

HOPKINS: It’s important to do it for the passion, the sheer enjoyment, the life force, but to not take it too seriously.

PITT: Fuck it.

HOPKINS: Fuck it! It works. I think, sitting here, that it sounds very touchy-feely, but it’s that infant side of us. I carry a photograph of myself in my phone, of when I was just a little boy on the beach. I look at him and I say, “We did okay, kid.”

PITT: When you say that, I don’t think you’re talking about worldly success.

HOPKINS: No.

PITT: I think you’re talking about the game of being human.

HOPKINS: Well, it’s such a mystery when our first memories are made. I can remember that day on the beach with my father. I’d been crying, because I’d lost a little candy he had given me in the sand. And that frightened little boy—who was destined to grow up and be an idiot at school, clueless, alone, lonely, angry, all those things—I look at him and say, “We did okay.” And the fact is that one day we’ll be gone. Our parents are gone. Most of my friends I’ve known have gone. I was driving around Venice the other day, and I thought, “It’s all a dream. What a struggle it all is. It’s all an illusion, but it’s the glory of life, the sheer glory of looking for it in everything.” And I’ve become aware of that now, more than ever. It’s in there. It’s in my cat, it’s in my dog, it’s in you. How could it be otherwise? I watch my cat jumping to a little pinch on the fireplace. Now, he can’t write a book, he doesn’t know anything about philosophy or mathematics. But how the hell does he do that? That is totally awe-inspiring.

PITT: What I hear you saying is that as we get older, we get out of our minds, and we’re able to witness the beauty and the wonder that we’re surrounded by in every minute detail. We miss that when we’re young.

HOPKINS: We’re too busy.

PITT: With our own hubris.

HOPKINS: But that’s a necessary part of growing up. Are you feeling that rising power of life?

PITT: Very much so.

HOPKINS: It shows in you.

PITT: I really feel it outside. I feel it in nature, which I did have moments of when I was a child. But I’m so much more aware of it now, and more in tune with it. There’s so much mystery and so much wonder, and I’m good with that.

HOPKINS: It’s great, isn’t it?

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Grooming: Sonia Lee for Exclusive Artists using Alba 1913.

Photography Assistant: Alexandre Jaras.

Fashion Assistants: Abi Arcinas and Christina Corso.

Production Assistant: Jack Tavcar.