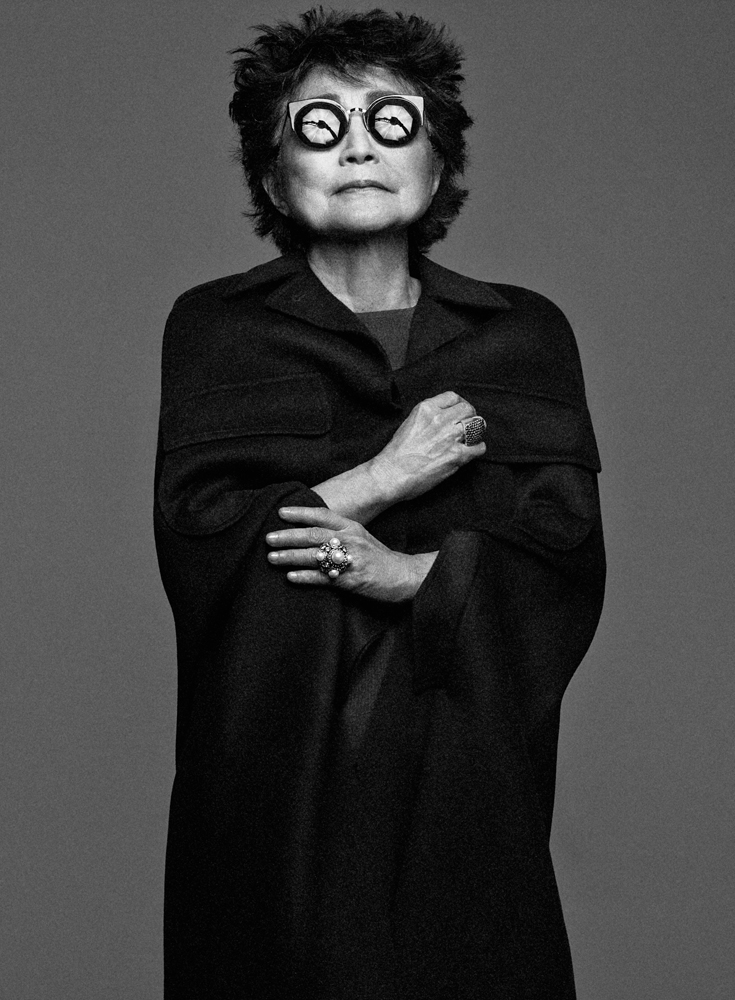

Yoko Ono

Art is life . . . It’s about living, but it’s a way of making your life elegant. Yoko Ono

It’s true that a smile can take years off a person—not that such a thing matters in Yoko Ono’s case. Ono doesn’t look 80 years old in the first place (though, remarkably, she is), and the smiles that she flashes over the course of our conversation—out of joy, or because she’s pleased with something that she’s said or heard, or even just the glimmer of a smile that creeps across her face before she laughs—render her completely ageless.

If anything is making her happy, perhaps it’s the fact that she now seems to have the world on a string. She started gathering it around her finger more than 35 years ago, when the B-52s famously appropriated Ono’s thrills-and-trills vocalization into “Rock Lobster”; suddenly, the name Yoko Ono was no longer synonymous with cacophony-as it had been throughout most of her marriage to John Lennon, her more experimental leanings repeatedly offending the pop sensibilities of Beatles fans. For years, Ono’s work—musical and otherwise—was, in large part, dismissed and derided; at best, it was often misunderstood. She was also subjected to attack after attack for what some imagined to be her role in Lennon’s life and the dissolution of his band, which was no doubt a factor in the public perception of her both as a woman and as an artist. But before her marriage to Lennon, Ono’s impact was being felt in subtler ways through the work that she accomplished in the ’60s as a proto-performance artist after aligning herself with the avant-collective Fluxus, as well as a New York experimental—arts solar system that included John Cage, La Monte Young, and George Brecht. Between them, they changed the gravitational pull of the art world. Ono provoked audiences, even daring them to join her in the making of the art in work like 1964’s Cut Piece, in which she sat onstage in a pantsuit with a pair of scissors and invited people to come up and cut her clothes. In that piece—as well as many others—she also invited them to join her in embracing the notion that art could be something that was experienced, or something that was literally broken, rather than something that was necessarily confined to the limits of a space or a frame. For Ono, it was about the breaking with tradition—including the one in which she was raised in prewar Japan—by sundering perceived barriers, forcing herself to be radical, and grappling with (and sounding the alarm for) the new.

Now, Ono is in the midst of a remarkable late-career renaissance, if not a full-on reappraisal. There is, of course, her unlikely emergence as global dance-music phenomenon: This year alone, she has twice twirled and slinked her way past such artists as Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Daft Punk, Katy Perry, and Justin Timberlake to the top of Billboard’s Hot Dance Club Play Chart, scoring her 10th and 11th such placements there since 2003, when a remix of 1981’s “Walking on Thin Ice” made it to No. 1. (The original was the last song that she recorded with Lennon, just before his murder.) In June, she curated the Meltdown festival in London, and in addition to her son, Sean Lennon, its lineup also included artists like Patti Smith, Siouxsie, Peaches, and Lene Lovich—an assemblage of talents that have, in a lot of ways, operated in the vicinity of her shadow. Earlier this fall, she also released an album of new material with Plastic Ono Band entitled Take Me to the Land of Hell (Chimera), a varied and energetic collection of songs featuring contributions from Sean, Beastie Boys Mike D and Ad-Rock, Questlove of the Roots, Merrill Garbus (Tune-Yards), Nels Cline of Wilco, and the members of Cibo Matto, and she has been performing music from it around the world. She has continued to flex her muscles as an activist, among other initiatives, helping to lead a campaign of Artists Against Fracking. Then there is “Half-a-Wind Show,” a traveling retrospective of her more than five-decade career as a visual and performance artist currently on view at the Kunsthalle Krems in Austria, and Acorn, a new volume of pithy reflections that serves as a follow-up to her landmark 1964 artist’s book of “instructions and drawings,” Grapefruit. (Intriguingly, many of the thoughts and ideas printed in Grapefruit read now, almost 50 years later, like Tweets in search of transmission.) Ono’s iconoclasm—which, for so long, resulted in thoughtless broadsides and hurtful assaults—has led to a legacy that has now helped shape generations of artists. If not always of her time, then she is now acknowledged to have been frequently ahead of it—always outlasting and out-loving the haters. Even Paul McCartney has come around: in a recent Rolling Stone profile, in which he belatedly absolved her of responsibility for the break up of the Beatles, he called her “a badass.”

Ono, though, has continued forged ahead—one might even say pirouetted—as she has remained determined to keep moving, like she does in her new video for “Bad Dancer,” throwing herself completely into the rhythm. That indefatigable smile is visible in that video, and I certainly noticed it while in her presence. Sometimes her smile even has the effect of making you feel like you’re sitting across from the mythical feline that she refers to in her new song “Cheshire Cat Cry,” as when the subject of a younger artist being influenced by her comes up: “Maybe,” she demurs, “but I think they’re pretty original on their own.”

On “Revelations,” a song on her 1995 album, Rising, Ono sings, “Bless you for your anger / It’s a sign of rising energy / … Bless you for your greed / It’s a sign of great capacity.” When Ono and I met at her studio in SoHo, I told her that those lyrics have been a touchstone for me. She uncorked the first of the age-shattering smiles that she shared during our conversation and said, “That’s very sweet”—as if there was no other conceivable response to a world out to trip you up than to dance around the outstretched legs.

ELVIS MITCHELL: Did you record Take Me to the Land of Hell here?

YOKO ONO: Not here in this studio, but in New York City, yes.

MITCHELL: How do you work when you’re making on an album? Do you spend some time writing songs and then start to put it together?

ONO: I just get inspired, and when I’m inspired, I jot things down and put them in a pile. With this album, I was thinking that it was about time to do something, so what do I have? And then I just kind of went through the pile.

MITCHELL: Do you like playing these new songs?

ONO: “There’s No Goodbye Between Us” is pretty nice to play. But that’s the kind of thing that was in the pile. I think it was toward the end of the ’80s or maybe in the early ’90s when I first wrote it because a friend of mine who is a very good singer—a famous good singer—she doesn’t write her own songs, so she said, “Write one for me.” So I just wrote it. But then she didn’t use it! [laughs]

MITCHELL: It’s almost like a ’60s pop song in a way. It’s very different from the other songs on the album, but each song on the record seems different from the one that precedes it.

ONO: I like to do it that way. I like to jump around like that.

MITCHELL: I saw you do another song, “Cheshire Cat Cry,” with your son, Sean, and the Flaming Lips on David Letterman. That line, “We the expendable people of the United States / Hold these dreams to be self-destructive …” is very powerful. It feels like it relates a little bit to the anti-fracking campaign that you’ve been involved with [Artists Against Fracking, which Ono founded with Sean in 2012].

ONO: Well, I changed the words a little when I did it on Letterman. I also changed it when I put a full-page ad in The New York Times because I just didn’t want people to get so hyped up about it. But it was the first thing that I thought of.

MITCHELL: That was the first song that you wrote for the album?

ONO: The first one was probably “Take Me to the Land of Hell.”

MITCHELL: What about “Little Boy Blue Your Daddy’s Gone”? There’s that lyric, “Little boy blue / Blow your horn / Mommy’s sleeping / Daddy’s gone …” Was that something you’d worked on for a long time?

ONO: No. I don’t work for a long time on anything. [laughs] I don’t have too much time in life, you know.

MITCHELL: When I hear your voice, though—especially on a song like that one—I always find myself thinking about what a precise singer you are. Does that come from training?

ONO: Maybe. I don’t know. I mean, it was like that before training, and that’s why I went into training.

i wasn’t sure if people would get it. i wasn’t creating for people. I was creating for myself. Yoko Ono

MITCHELL: One of my favorite songs of yours is “AOS,” which is the one you did with Ornette Coleman, where you sing with the trumpet. [The song, recorded live with Coleman in 1968, appears on Ono’s debut with the Plastic Ono Band, 1970’s Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band.] You really get a sense of what a powerful singer you are and how much control you have.

ONO: Thank you. But, you know, the thing is that I was like a … People didn’t respond positively to my songs back then, as you know.

MITCHELL: Well, people who knew music responded to your songs. You must have heard from some people who liked that particular song at the time.

ONO: Right away? I don’t know. Not being appreciated for 40 years or something … It feels like I was accused of something that I didn’t do, which was breaking up the Beatles. That was like being somebody who is in prison without having done anything wrong. It’s like you’re accused of murder and you’re in prison and you can’t get out. That’s why I finally came to the conclusion to use that big energy of hatred that was coming to me and turn it around into love.

MITCHELL: When did you figure out to turn it around like that?

ONO: Well, it happened because I was kind of alone. I wasn’t valued by people, or if they did value me, it was in a particular way. So I started to feel that if no one else loved me, then I had to love myself. I thought, “Darling, you know you work so hard. You are always trying to do good. But somehow it’s not being appreciated. I feel sorry for you.” That’s what I was thinking at the time—and I kind of like myself for being that one who survived regardless.

MITCHELL: It’s interesting to hear you say that, because you’ve always seemed to be about sticking to what you believe no matter what people say.

ONO: Well, there are two sides of the coin. One side is saying, “Poor darling …” and then the other side is saying, “Hey, you know? You’re right.” [laughs]

MITCHELL: It’s good to see you smile because there has always been something playful about your work. I feel like whenever I read these pieces that you’ve done, like the ones from Grapefruit [1964] or the new book, Acorn, there is always a smile in them. I love this bit from the true or false section of your piece “Questionnaire” in Grapefruit: “All fruits are related species of banana, which was the first fruit in existence. The Bible lied about the apple because they felt mentioning the word banana too undignified.”

ONO: I like to play around. Do you know that piece I have that’s sort of like a needle sticking out of the glass, and the title is Forget It [1988]? Once you say that, nobody can forget it.

MITCHELL: But then, so much of what you’ve done has also been about seizing the moment.

ONO: Yeah. That’s all we have, moments. A series of moments.

MITCHELL: People sometimes start thinking so far ahead, though, that they get lost or stuck. But you’ve always seemed to have the ability to move past that.

ONO: Well, I think one of the things that saved me is the fact that, luckily, I see the totality. I’m always looking ahead, and if there is no possibility to look ahead, then I despise that situation.

MITCHELL: Have you always been like that?

ONO: Always, yeah.

MITCHELL: I’m looking at this new book, Acorn, which is a follow-up to Grapefruit, and I’m thinking back to the bed-ins, and even before that, when you and John were talking about planting acorns. [In 1968, Ono and Lennon planted a pair of acorns for peace at Coventry Cathedral. Then, after their 1969 bed-ins, they sent acorns to numerous heads of state, with the hope that the recipients would plant the “living sculptures” as symbols of peace. Both the bed-ins and “50 acorns tied in a sack” are referred to in the song “The Ballad of John and Yoko.” Ono repeated the “Acorn Peace” mailing in 2009.] While so much of what you’ve done has been about being in the moment, you’ve also always seemed to be planting seeds for the future in some way.

ONO: It’s very interesting because a few months ago, somebody sent me some pictures of a beautiful tree that I would guess was maybe 300 years old—it had all of these big knobs and things growing around it. So, I go, “Wow.” And this guy said that when John and I talked about planting the acorns, he thought he’d do it, too, so he did it then, and the tree in the picture is actually not a very old tree. It’s about 45 years old, not 300. So I said, “You mean a tree gets like this in 45 years?” In other words, the first acorns we tried to plant were stolen—you know, gone. But the concept is there. We planted the concept. So he grew the seeds within his garden. Isn’t that great?

john was very much like me . . . i think it was very difficult for him to stick to being part of the band. Yoko Ono

MITCHELL: That’s beautiful. I found myself thinking it because so many of the acorns that you and John did plant are, in a way, still growing.

ONO: I was able to go on and on and on doing what I was doing because what I was doing was rejected. So it’s a blessing, in a way—a very strange blessing. Because if what I was doing back then would have been totally accepted—you know, “Now, Yoko, do that one again! We love it!”—then I would have been dead as an artist, stuck in one place. But I couldn’t get stuck in one place because people kept whipping me, so I always thought, “Go on, do another thing.”

MITCHELL: It was sort of a pivotal moment when you and John started working together and did the bed-ins in 1969, the second of which is documented in the film Bed Peace [1969]. You were in bed on your honeymoon—this very private moment in your life together. It’s a thing that most people don’t talk about—that people like to keep to themselves. The impulse is to keep others out of the bedroom.

ONO: Yeah, exactly.

MITCHELL: But to say, in 1969, “We’re inviting you all in …” I mean, not that this matters, but on a very basic level, this was a moment when fictional couples in American movies and TV shows were often still portrayed as sleeping in separate beds.

ONO: I know. Isn’t that amazing?

MITCHELL: So the idea of you two, being who you were, and then getting into this bed together and inviting people to come be into the bed with you … It was a big deal.

ONO: I think we destroyed many, many myths.

MITCHELL: I was watching the “Bad Dancer” video, which starts with you painting before you begin to dance. I saw you on a British TV show a couple of months ago, and it showed some footage of you dancing as a 3-year-old.

ONO: When I hear music, my body just starts to move. It has nothing to do with training or anything. That’s just me. That’s just my body. And I was like that as a child, too.

MITCHELL: When you play music live, do you get nervous before you go out on stage?

ONO: I get very nervous before I get on the stage, but once I’m on the stage, I’m just, you know, me. Nothing hurts me.

MITCHELL: What makes you nervous beforehand?

ONO: That I want to hit that really beautiful mark, and maybe I won’t be able to hit it or something.

MITCHELL: That “Bad Dancer” video seems to involve every part of your being and of who you are. It’s like you’re throwing the entirety of yourself into it as an artist.

ONO: But, see, I don’t particularly consider myself just an artist. I’m a woman—I’m a human being—and there are a lot of situations that that covers.

MITCHELL: For the most part, though, people do seem to call you an artist and address you as an artist, don’t they?

ONO: No, I don’t think so. I think they first address me as the wife of John, the widow, and the person who broke up the Beatles.

MITCHELL: That was a little while ago, though, Yoko …

ONO: Five minutes ago.

MITCHELL: But even Paul McCartney is saying now in Rolling Stone that Yoko is a badass—although, it took him something like 45 years to do it.

ONO: I don’t know … It’s a strange feeling, you know, because I’ve been sort of trained … Well, not trained. I was going to say I “trained” myself—and maybe I did train myself to feel a certain way. But I just felt always frightened, struggling. But then suddenly they’re saying, “No, you don’t have to fight. We understand you!” It’s like you’ve been knocking on the door for 40 years and then someone suddenly says, “You don’t have to knock on the door—the door is already open.” Oh … Okay! So how are you going to deal with that? And I have to be very cautious. It’s better that you’re criticized than complimented as a person.

i was kind of alone. i wasn’t valued by people . . . and i kind of like myself for being the one who survived regardless. Yoko Ono

MITCHELL: You think so?

ONO: Oh, definitely, because if you’re criticized then you can use it as an experience. Compliments, you can’t use.

MITCHELL: So when people compliment you, does that make you uncomfortable?

ONO: Well, basically, there was a silent criticism that was happening, and that was very good back then.

MITCHELL: But when people compliment you now, how does that make you feel?

ONO: There are many reasons why people compliment somebody.

MITCHELL: Well, what about if someone was complimenting you because they like your work?

ONO: That’s very sweet—I appreciate that. But these days, when you go to hotels or somewhere like that, they always have a mirror, but the mirror doesn’t really reflect you. It just suggests, like an airbrush thing of you. And if you keep looking at what you see in that mirror, then you can’t really deal with your real face.

MITCHELL: As you say that, I’m thinking about how some of the instructions in Grapefruit are about breaking mirrors. There is also that song from Between My Head and the Sky [2009], “The Sun Is Down!” where you talk about throwing away the mirror. The idea of doing away with or not regarding the mirror has been an idea that kind of runs through your work.

ONO: Well, there’s that, but then, as I said before, there are two sides to the coin. You have to break the mirror, but you also have to see the mirror. You have to have that dichotomy constantly. If we don’t have that dichotomy, then we become sort of two-dimensional. We become like a painting, not a person.

MITCHELL: There’s also the precision with which you do things, and then, at the same time, the way that you also want to get lost in things. It’s like some part of you also loves the idea of contradiction. Do people—other artists—ever talk to you about that?

ONO: You know, I don’t think that I have too much time to talk to people—and that’s good, too. I don’t really believe in going with somebody to have tea and chat. I don’t do that. It’s just a waste of time. [laughs]

MITCHELL: Your work has never entirely been built around creating objects. In fact, much of it has been about burning, cutting, or shattering objects, which was sort of a radical thing to do in the early 1960s—

ONO: Maybe, but, I mean, the world is full of that.

MITCHELL: But to come out and say at that time that art is not this thing that needs to exist permanently—that it can be about a moment or an experience—was radical. You were at the vanguard of what could be called public art—art that was not just something to be shown in galleries or hidden away in someone’s home. Do you remember when that idea started to dawn in your consciousness?

ONO: About the fact that I should ask for participation? I think that notion or concept was always somehow at the edge of my consciousness.

MITCHELL: That idea is all over Grapefruit. In fact, that book, which you first published in 1964, is almost like a schedule you set out for the future. There is a section where you talk about making a painting, a design, or photograph, and letting visitors cut out their favorite parts and take them. In a way, you almost predict what you would do a few years later with Cut Piece [1964]. [In the early ‘6os, Ono performed Cut Piece in Kyoto, Tokyo, New York, and London. For the first performance piece, she sat onstage wearing a white suit and invited viewers to participate by cutting away any piece of her clothing they liked with a pair of scissors and taking it. Ono performed the piece again in Paris in 2003.]

It’s about trying to create a new experience for everybody . . . reality can be elastic, and i want to see how elastic it can be. Yoko Ono

ONO: I know. Amazing, if you think about it … I just liked the idea that I wouldn’t control the whole thing. In Grapefruit, I’m saying to cut all the red parts so that what happens is not controlled. But just by saying that, just by giving that instruction, I’m sort of freeing the piece to other people.

MITCHELL: When you performed Cut Piece for the first time, was it about letting go of that control and allowing other people to be a part of it as well?

ONO: I just thought it was a good idea—that’s all. I thought it was a good idea as art. I mean, for the “bottoms” film [No. 4 (Bottoms), 1966, an 80-minute film that consists solely of close-up images of naked buttocks walking], people ask, “How did you do that film?” Basically, I saw an image of it, just that bottom, and I’m seeing the full part filling the screen, and I’m thinking, There’s not a film where one object is filling the screen. Usually the object is somewhere in some kind of landscape or against the wall of a room or something. But there is usually something in the frame that is not the object. So I thought it would be very powerful to do something where it was all the object. So it’s all just sort of art ideas.

MITCHELL: You’ve always invited people to be part of your work, though. That feels like a very generous impulse to me.

ONO: Well, that’s the danger of suggestion, you know. So when I first thought about it, I was like, “Am I going to let people participate in the work?” I was just not sure because artists don’t want to do that—they usually want to just perfect something and never let people touch it. So I thought that’s why this could be good, because it’s very different. It even goes against my feelings—I don’t want to give up the control. So it must be good.

MITCHELL: So in a sense, you were even rejecting your own feelings as an artist to do that.

ONO: Yeah. Isn’t that great?

MITCHELL: It must have been scary, too. What was it like the first time that you invited someone up on stage with you or to participate in a piece?

ONO: Oh, it was very scary. It is very scary. But it’s also like some kind of scientific logic. From the beginning to now, I’ve had the same relationship with it.

MITCHELL: You’re asking for the unpredictable when you give up control—you don’t know what you’re going to get. Do you like the sense of scariness that comes with that?

ONO: No, I don’t, because I’m a person who believes in great taste, and with anybody who is going to come in and participate, if I don’t think that this person has such great taste, then what am I going to do? But in a way, it goes against my snobbery, so it is very good. [laughs]

MITCHELL: Do you feel like you’re a snob by nature?

ONO: Well, maybe that’s too unkind a word for me. It goes against my pride. But it’s almost like giving love.

MITCHELL: And trust.

ONO: An artist doesn’t have that kind of love. It’s kind of like before having that love, artists have more love for themselves. But the pride that I have maintained—or retained—is in the fact that I could even go against myself to create a very beautiful thing, which was the format of the art.

MITCHELL: More than making things, art, for you, seems to be about the way that you live your life.

ONO: Art, for me, is about survival for my mind—like, if I don’t do these things, then I might become insane or something. So it helps you keep your sanity just to do it. You have to release your emotion in order to keep your sanity.

MITCHELL: There’s so much in Grapefruit about freedom and being free.

ONO: Exactly.

i was accused of something that i didn’t do, which was breaking up the beatles . . . it’s like you’re accused of murder and you’re in prison and you can’t get out. Yoko Ono

MITCHELL: In the early ’60s, it was still a fairly subversive thing, though, to say that you should take a painting, cut it, set it on fire, step on it, hammer nails into it … Do you remember how people responded back then when they first saw these things?

ONO: Well, I gave a show in June 1961. It was very hot—there was a heat wave in New York City later that summer. But only about four or five people came to see the show, and I knew their names—they were all very close friends.

MITCHELL: But even going back to the “instruction” paintings and earlier pieces, where you were asking people to participate, there has always been a fluidity to your work. When I think about some of the work that you did with Fluxus …

ONO: Well, if you don’t have fluidity, then I think that you are finished in a way.

MITCHELL: When you met George Brecht and La Monte Young and the other people involved with Fluxus, did you connect with them right away?

ONO: Well, some of what we were interested in was the same, but we were all very different people.

MITCHELL: Do you remember the first time you met La Monte?

ONO: All I remember is that he took off his sweater, and he was wearing a shirt that had all these holes and ripped parts. I saw that and said, “Well, that’s cool.” But we were the kind of people who didn’t discuss so much about art or philosophy. We worked. I didn’t really even listen to other peoples’ music back then. Whenever I did, I did mostly just by chance. I found other stuff was boring—that’s why you make your own. Everything was of me and natural to me. That’s why things happened. Art is life … It’s about living, but it’s a way of making your life elegant.

MITCHELL: Is that important to you—to live your life in an elegant fashion?

ONO: Yes, it is. I mean, we could be monkeys and just eat bananas and scream all day or something. Or we could have coffee in the morning. We created a thing called culture and civilization, and now we’re about to lose it because we’re trying to destroy everything. And I kind of miss it. I miss culture and civilization.

MITCHELL: Is that what you grew up with, that kind of culture?

ONO: The culture that I was brought up with was not like this. This is like a rebellion to that culture.

MITCHELL: Still, even though you rebel against that culture, it is a strong part of who you are.

ONO: Yes. It’s an almost annoyingly strong part.

MITCHELL: Was it difficult, then, for you to decide to reject it?

ONO: No, because even just recently, I thought, Well, I don’t want to start thinking like my mom … You do get like that.

MITCHELL: You’re the last person I would expect to hear say something like that.

ONO: I know. Just being honest! [both laugh] But it’s about trying to help create a new experience for everybody—the kind of world we’ve never encountered before, to stretch reality. Reality can be elastic, and I want to see how elastic it can be, you know? I don’t know why I started to create … Well, I think one thing I know is that I didn’t want to repeat what was in the culture already. I wanted to go forward.

MITCHELL: When did you figure that out?

‘Am I going to let people participate in the work?’ i was just not sure because artists don’t want to do that—they usually want to just perfect something and never let people touch it. Yoko Ono

ONO: I know that you’re going to think that this doesn’t sound real, but it was when I was 4 years old. I kept thinking about all these incredible things. Some of them were not incredible, but I thought they were incredible, like, I went to my mother’s garden and saw some plum trees and some apple trees, and I was saying, “Why don’t we put the two seeds together and we will have apple-plum trees?” I was thinking that this was a real discovery … But it’s interesting, because instead of just thinking about it, I was also always thinking, Well, we have to tell this to the world. [laughs] We have to share the discovery. Granted, I didn’t share my discovery when I was 4, but you know …

MITCHELL: When you were making the kinds of statements that you were, early on—even in the instructions in Grapefruit about prizing the moment and not worrying about owning things—did you think people would reject those ideas in the way they did?

ONO: I wasn’t sure if people would get it. I wasn’t creating for people. I was creating for myself.

MITCHELL: But then, at the same time, you were also talking about the importance of sharing your art. I mean, that book is referred to as a book of “instructions”—for other people.

ONO: But the sharing automatically happens.

MITCHELL: It seems to have taken a while, though, for people to be able to share what you had to say back then.

ONO: I think that some artists have pride, though, in going into the future. I was always comparing myself to Madame Curie. I was just discovering, discovering, discovering things, and I would write down my discoveries for people to see 10, 20, 100 years later. That’s how I was looking at it. So I was not accommodating the people of that particular time.

MITCHELL: You really weren’t. [both laugh] But was not accommodating them something that you enjoyed doing or something that you felt like you had to do?

ONO: Well, see, that’s the difference between entertainment and art. People just love to be entertained, and in order to entertain them, you have to do things in a way that they understand. So automatically, you have to go to a certain place, and I wasn’t doing that. But then, also, I really think that any invention or discovery cannot be done unless you are totally free—free of those people.

MITCHELL: I think there are some people who have this thing where, from the very beginning, some part of them rejects convention. You seem like you were one of those people, like you couldn’t help yourself.

ONO: Exactly. That’s a good way of putting it.

MITCHELL: Were your siblings like that?

ONO: No. My brother and my sister were both very different from me. I’m the Robinson Crusoe, alone on the island that I was born on.

MITCHELL: Did that ever feel lonely?

ONO: Again, I think that there are two ways of going. One is to be so upset about being alone or loneliness so that you start to change yourself. And then the other is that you just get used to the situation. But each time you discover something more, you move away from other people, you become more distant and different.

MITCHELL: But at various point in your life, you’ve found other people who were on similar paths, whether it was with Fluxus or with John or with the musicians you’ve played with for a long time. You’ve found these small tribes and made yourself a part of them.

ONO: John was very much like me.

MITCHELL: Did you see that in John immediately?

ONO: John was like that, and I think it was very difficult for him to stick to being part of the band.

MITCHELL: When you met him, was it like you showed him that door he’d been knocking on that he didn’t realize was already open?

ONO: I didn’t have to open it. John opened it and came in.

MITCHELL: From the outside, it seemed like John was an entertainer who was ready to be an artist when he met you.

ONO: Well, he was an artist from the beginning, so there was a certain loneliness that he was feeling in the band probably.

that’s the difference between entertainment and art. People just love to be entertained, and in order to entertain them, you have to do things in a way that they understand.Yoko Ono

MITCHELL: When you and John first started to work together with Plastic Ono Band, what was the atmosphere like? Was there a sense of fun in doing it, or were you consciously trying to push boundaries?

ONO: Sense of fun … Ha-ha kind of fun was not there. It was more like when you’re mediating in Zen. You’d feel sort of like a different kind of pleasure, I suppose.

MITCHELL: Maybe “fun” is the wrong word. But did you find a pleasure in doing something new together and trying to break boundaries?

ONO: Yes, definitely.

MITCHELL: It’s interesting, though, to hear you talk about how that Beatles chapter still casts a shadow for you, because, to me, it felt like people who didn’t understand you didn’t want to make the effort to see you or hear you.

ONO: Well, I was so different from them in a way. But John saw the difference. It’s almost like a certain animal that cannot respond or have life in any other way. So, you know, sometimes you’d feel, Oh, god, this is not very good for me, and that’s the thing that is creating this gap. You can call it a difference or a gap or whatever.

MITCHELL: You must be very happy then with this traveling retrospective, “Half-a-Wind Show,” that’s in Kunsthalle Krems, in Austria, right now—that you’ve arrived at a point now where people can appreciate what you’ve been doing all of these years. What’s it like for you now to have that happen?

ONO: I just feel very, very good that a piece like Half-a-Room [1967] can now be shared. When I created Half-a-Room, I never thought people would understand it. I wasn’t getting along with my husband, and then one morning, I woke up and saw that the other side of the bed was empty. I thought, “This is incredible. I could just make half a room.”

MITCHELL: Even with something so personal as Half-a-Room, there’s an invitation for people to fill that part of the space. Does it feel odd to you to be part of a big exhibition that’s going around the world?

ONO: No. I have so many different ways of being creative, I suppose, and what I’ve realized is there’s a big difference between sending your art in a statement or something like that, and sending yourself there. When you send yourself somewhere, then you are sharing your information uncontrollably—like all yourself. You’re already communicating things with other people on the level of what they want to be communicating without asking my consent. So when I’m just standing there, I’m very aware that 80 years of my experience is what I’m giving. You see, no matter what we try, everything we make automatically changes.

MITCHELL: You were talking earlier about how criticism can be good for you, but it seems like at least some of the criticism that you’ve received at various points was in a key that you couldn’t hear.

ONO: It’s strange that you’re saying that because John used to love watching the TV without putting on the sound.

MITCHELL: And the people who thought of you as the woman who broke up the Beatles or the woman who didn’t understand music weren’t really looking at or listening to what you were doing—they were just paying attention to what other people were saying. But it seems like you were built, on some level, to not care about what other people say.

ONO: I know. Isn’t that funny?