Superstar

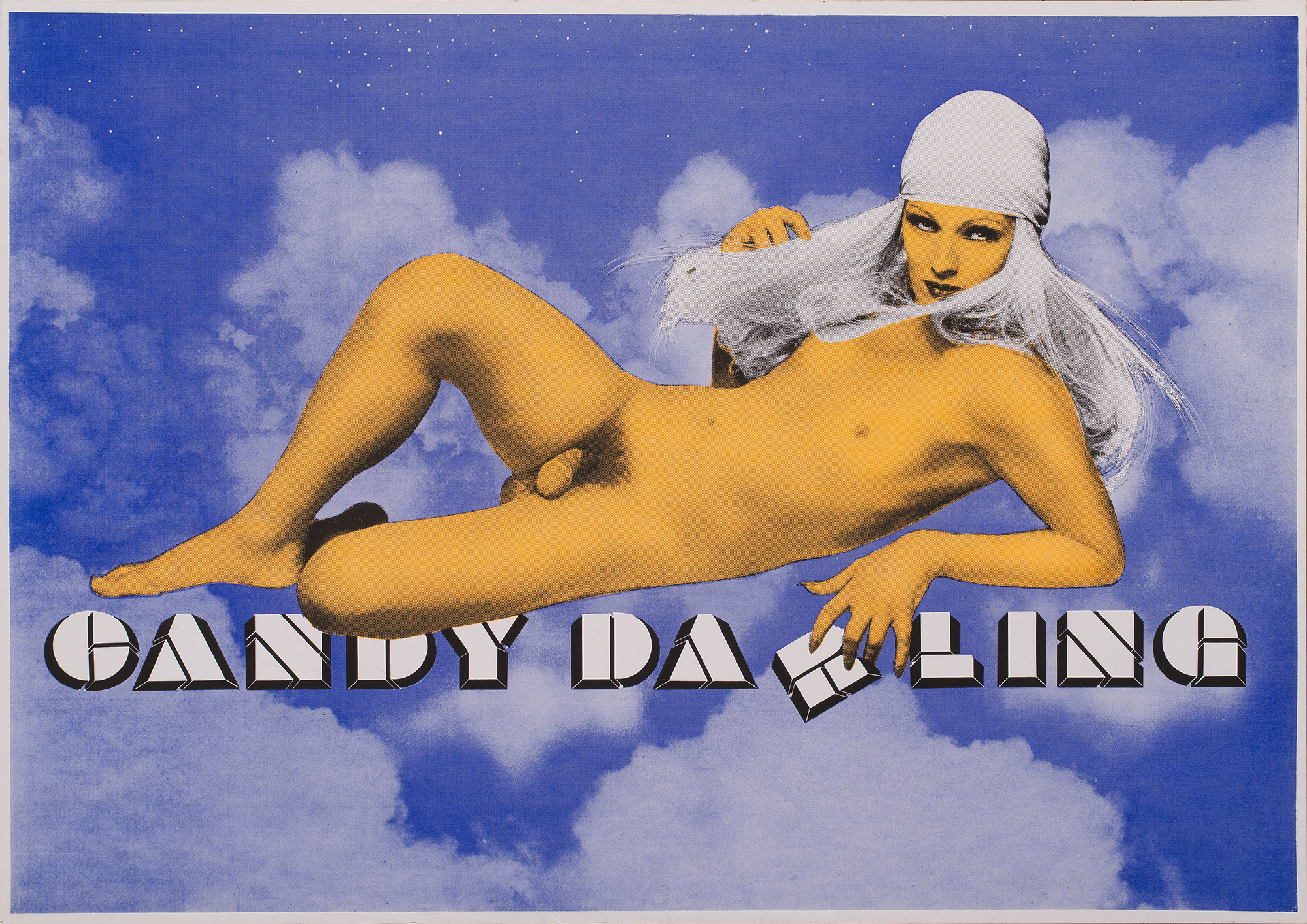

Who Is Candy Darling? Behind the Mystique of the Ultimate Warhol Superstar

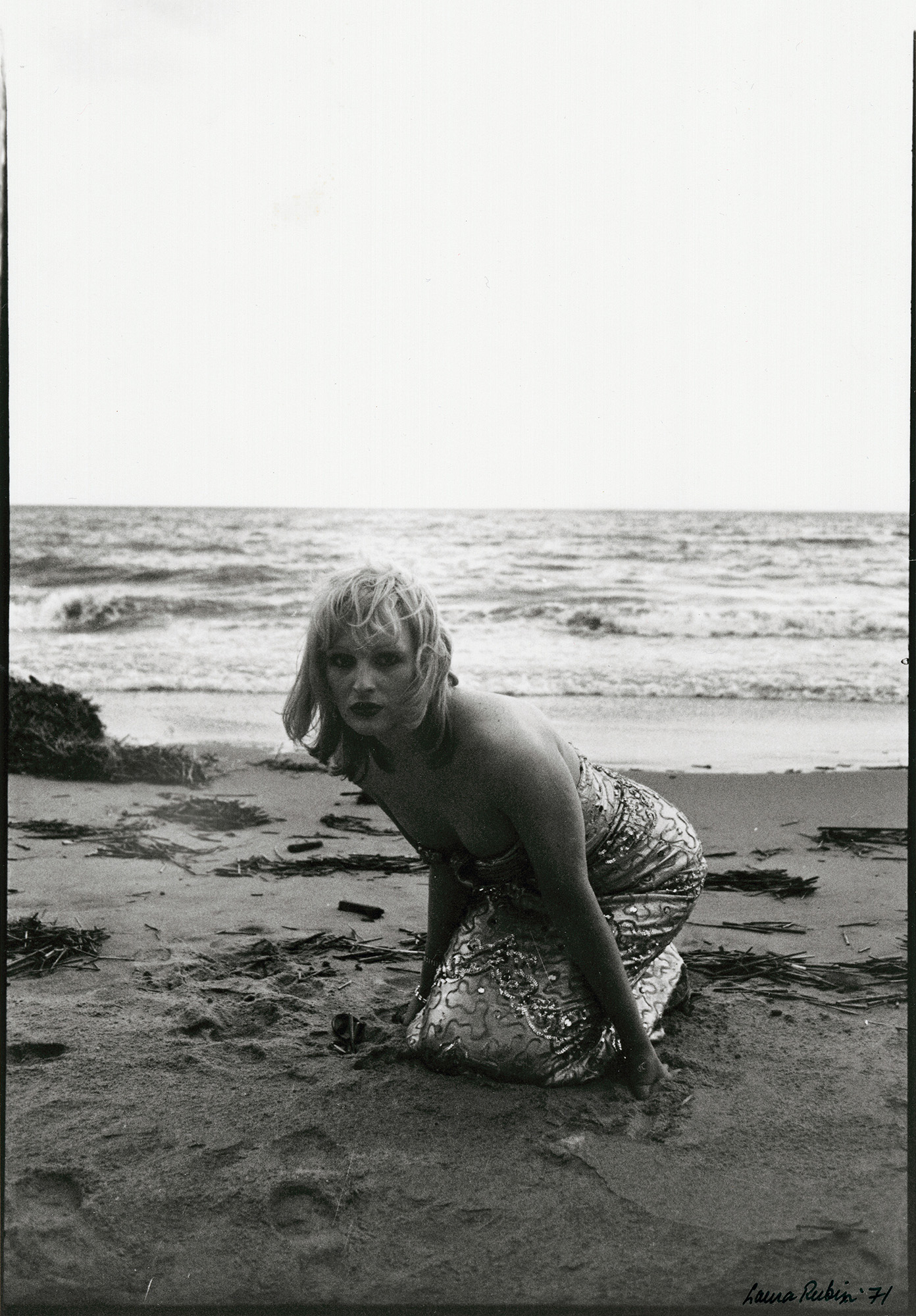

Candy Darling Silver Gown, 1971. Photographed by Laura Rubin. Courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. Gift of Laura Rubin.

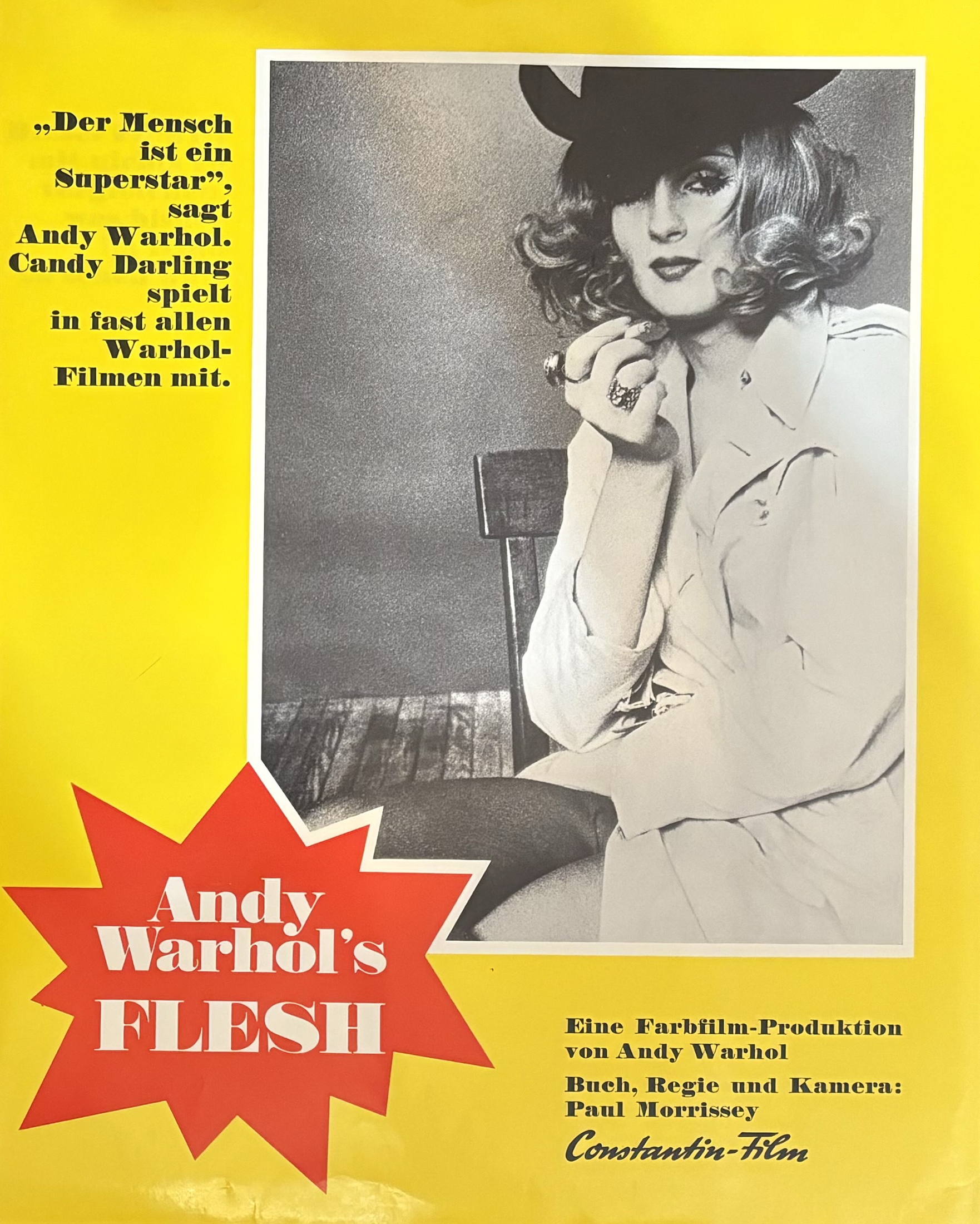

Who was the ultimate Warhol Superstar? A heavy favorite would be the ravishing blond bombshell Candy Darling. Then and now, Candy represented not only the subversive glamour of 1970s New York—and more particularly, of Andy Warhol’s inner circle of gorgeous and decadent misfits—but also willful self-reinvention. She proved that an awkward, queer kid growing up on Long Island in the 1950s could transform herself into a legendary beauty who stole the spotlight onstage, onscreen, and at an endless parade of parties. Until today, Candy Darling might have been best remembered from the Lou Reed song, or the 1973 deathbed photo by Peter Hujar, or the two Warhol-Morrissey films in which she appeared. But now, biographer Cynthia Carr has written Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar, the definitive record of her life, shading in the vulnerable, gritty, and deeply soulful individual behind the fabulous facade. Carr, who previously penned a bio of downtown artist David Wojnarowicz, chatted with Interview’s editor-in-chief Mel Ottenberg about the mystique and magic that was—and always will be—Candy.

———

MEL OTTENBERG: Hey, Cynthia.

CYNTHIA CARR: Hi, Mel.

OTTENBERG: I loved the book. Oh my god, it’s an essential read for anyone interested in queer culture and New York history. I feel like it’s really written for the fans.

CARR: I think so. Also, I found out lots of things that people didn’t know. That world, especially the Warhol part of it, has been so covered, but still there were things I hadn’t known before.

OTTENBERG: I read it over the Thanksgiving holiday, and I’ve been skimming it again in advance of this call. It really is amazing how much dense, interesting information there is. If you’re interested, it’s all here. Thank you.

CARR: I worked on it for 10 years because the information was not that easy to come by. When I wrote about David Wojnarowicz, it was the same thing. It’s important to me to find what I think of as these hinge points in someone’s life. Like, you turn this way instead of that way, or this decision is made that’s so crucial for the rest of the person’s life. I think those show up here.

OTTENBERG: Why Candy now? Did you do it timed with the 50-year anniversary of her death, or did it just happen that way?

CARR: It just happened. I never thought I was going to spend 10 years doing this, that’s for sure. It started because her friend Jeremiah Newton called me. We had both been part of this odd downtown award ceremony called the Acker Awards, which was giving out awards to people who were keeping the downtown boho spirit alive. Jeremiah won for his documentary called Beautiful Darling. And then I won for my book on David Wojnarowicz. The next day, Jeremiah got my number, called me, and said, “I don’t know who you are, but when you came up on the stage, I realized you’re the person who should write about Candy.”

OTTENBERG: Oh wow.

CARR: I went over to his apartment to talk to him. Jeremiah had a lot of material. What intrigued me was, here’s this glamorous figure who knows Salvador Dalí, goes to Mick Jagger’s birthday party, and she’s at all of these fashion events. And then when she goes home to Massapequa Park, her mother is telling her, “Don’t let anyone see you. Don’t answer the door. Don’t go get the mail.” There’s that contrast, and I thought, “Whoa, there’s a story there.” It intrigued me that there was a real pathos in that life. I didn’t realize how difficult it was going to be. Jeremiah had some of the material in a top drawer of a dresser—some of her journals, photos, and letters. And he had some things at his house in Cherry Valley, where Candy is buried. But the rest of it was in boxes and boxes of her stuff at his apartment—Christmas cards, old tax documents, mixed research he was doing on Isadora Duncan, and, “Oh, it’s a letter from Candy.” Everything was just mushed together. He started telling me from the start about Candy’s interest in Christian Science, and that really surprised me. I don’t think people know about that. And he said, “She has this Mary Baker Eddy book, and she wrote in it, and she wrote comments in the margins and made underlines.” I looked for that book for years, and only found it when Jeremiah, at some point, went into the hospital. He may have been on the verge of getting evicted because of the squalor in the apartment, and he hadn’t been able to get out of bed. It was really a mess. A couple of people went in while he was in the hospital and took everything out and put it in storage, then put in a new floor in his living room, and painted. And then started bringing things back, although a lot of it was ruined and ended up in a dumpster, including some things of Candy’s that I had found and copied and then brought back to him. I saw everything that came back to his apartment, and a lot of Candy’s things got lost and are just gone.

OTTENBERG: But you found the book?

CARR: Yeah.

OTTENBERG: So you started with Jeremiah’s material, which contained a lot of interviews he did, and you went on your own from there.

CARR: I interviewed something like 92 or 93 people, some of them multiple times. The transcript of just my interviews with Jeremiah is longer than the book. But I was lucky because Jeremiah had done a lot of interviews in the 1970s because he was going to write her biography, and that was of crucial importance. Most of those people were dead by the time I started. He’d never even listened to those tapes, but I transcribed them.

OTTENBERG: I live a block from the Marlton Hotel, and I really enjoyed reading all the stuff about the neighborhood, like all the cruising fags on Greenwich Avenue. I had no idea! Tell me, who were the most memorable interviewees? Did you interview Gerard Malanga?

CARR: I did. That took a while to arrange because he wasn’t that willing.

OTTENBERG: Yeah, I figured.

CARR: It turns out he didn’t know Candy all that well. He was sort of on his way out at the Factory by the time Candy was part of it. But he took photographs of her, and lived near these friends of hers named Jim Hanafy and Leonard Barton, a couple she lived with for a while. So he was in that milieu. But one of the most crucial interviews came from Jeremiah’s tapes. He interviewed Candy’s mother. He also had some notebooks and letters that Candy’s mother had done, and it was touching, this part where Theresa Slattery, or Terry, as she was known, made notes about what she had gone through dealing with Candy’s transition. She transitioned in 1960 or something. Transgender people just were not visible at that point. TerryThat was a restaurant called Casey’s. wrote this whole account of taking Candy to a doctor and being told, “You have to allow Candy to be Candy, because sometimes people commit suicide if they can’t be who they are.” Terry really did listen to that, and she tried. She also had this sort of shame about the neighbors, but at the same time there was a part of her that I think was proud of Candy’s beauty and what she had accomplished. I think it was a very hard path for Candy’s mother. So it was very important to get those interviews and the material that Jeremiah had found.

OTTENBERG: Who else?

CARR: Another key person from that part of Candy’s life was Lorraine Newman, the beautician who hired Candy after she quit school. Candy went to beauty school for a while and was working for Lorraine. They became very close. Lorraine was very accepting of Candy as she was. She was talking to Lorraine about what name she should have, and Candy was one of the choices. As far as I know, she did not talk about that kind of thing with her mother, but she did talk to Lorraine about that. One person who ended up giving me a lot of information is Agosto Machado, who met Candy when she was hanging out with street queens. That’s another part of Candy’s life that people really don’t know about. Agosto was part of Vain Victory, the Jackie Curtis play, which was very important. He knew her till the end so he was an invaluable informant.

OTTENBERG: Fantastic. For Candy, there are eras, right? There is the street queens era. Then she graduates to Warhol, and he loved her more than any of the other Superstars. He cried when he found out she had cancer and no one had ever seen him cry. All that I found very, very interesting.

CARR: That’s the thing, I feel like you see a different version of Warhol in this book. He really liked her and he cared about her. Also, he was giving her money, and he has that reputation as a skinflint. If she was looking shabby he’d give her $50. I got that from an unpublished diary page at the Warhol Museum. I asked Jeremiah about it at one point, and Jeremiah said, “Well, the trick was to not ask him.”

OTTENBERG: Right.

CARR: I talked to Jane Forth, who was a Superstar. She worked at the Factory as a receptionist, and she didn’t remember very much about dealing with Candy at all, but I made some comment about people asking for money, and that she remembers. She said, “Oh my god, I couldn’t believe how many people came to the Factory wanting Warhol to give them money.” I’m sure that Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis did go ask for money and probably didn’t get much.

OTTENBERG: There’s a part in the book where Warhol is at a diner with Flawless Sabrina and Warhol tells the owner of the diner to give her ten thousand dollars.

CARR: And he did. That was a restaurant called Casey’s. Flawless Sabrina aka Jack Doroshow wanted to finish making her film called The Queen [directed by Frank Simon].

OTTENBERG: It’s an instance of Warhol being really selfless in that situation and not eating that whole moment up.

CARR: Right. What Flawless said was that Warhol thought the documentary should be done by people who had more clout than he could offer. They’d take the film more seriously than if it was a Warhol-esque sort of thing. And Flawless said, “I thought that was very insightful on his part.”

OTTENBERG: As a creative person, one of the things about your book that struck me was seeing someone who never had a stable life, who really wants to be a star, and is really doing a lot of creative stuff. Someone not necessarily with the most planned-out life choices, just doing the next interesting cool thing. Meaning she’s not just going for fame, she’s also really involved in the underground off-off-Broadway theater scene. Do you think that she was doing that because she was passionate about it, or was it just right in front of her, or did she see it as her key to fame and fortune?

CARR: First, she was completely accepted as who she was in that world. Her first play was the Jackie Curtis play Glamour, Glory and Gold. Then when he was doing Vain Victory, Candy wanted to be part of that. I don’t know what other options she would’ve had. I think she wanted to be on the stage and this was her chance. She wasn’t getting other offers, but I think she also really enjoyed working with Jackie, at least at the beginning. Jackie changed a bit, too. But this was a way to get noticed. And at the time of Vain Victory, she already had worked on the film Some of My Best Friends Are…, and Flesh, and a few other plays. So she already had recognition as a Superstar. And a lot of important people had seen her in Glamour, Glory and Gold. That’s how Warhol saw her, and Werner Schroeter probably saw her in Vain Victory. It was a big hit downtown.

OTTENBERG: I’ve got a Warhol itch. Particularly the films. Women in Revolt, Flesh, Heat, and Trash are being remastered.

CARR: Oh!

OTTENBERG: I have the DVD of Women in Revolt. I was gonna watch it last night before this interview.

CARR: I read the script for Women in Revolt in Jackie Curtis’ archive. George Abagnalo, who worked for Paul Morrissey and who appears in that film, told me that Morrissey would tell people, days or even a week ahead of time, what the scenes were going to be about and who was in them. I think Jackie wrote her own scenes, because often, they’re very funny.

OTTENBERG: They worked on that movie for a year.

CARR: Yes. Very long for a Warhol film. There’s a quick turnaround on most of them. I think Flesh was filmed in the summer while Warhol was in the hospital, and then it premiered in the fall. It was done really quickly.

OTTENBERG: Why do you think that nearly 50 years after her death, Candy remains?

CARR: Her beauty probably has something to do with it.

OTTENBERG: Yes. I wrote down this part she wrote in 1967 in a letter to her cousin Kathy: “You must always be yourself no matter what the price, it’s the highest form of morality.” So cool to hear that from 1967, like, “I am Candy Darling no matter what.” And they went hitchhiking in ’67 to Chicago in women’s clothes! These girls are tough.

CARR: In that era, people who were openly gender-nonconforming in any way, whether they were drag queens, or trans people, or whatever, you had to be really tough. It just was required because you took so much shit. And that statement from the letter, to me, that’s the core philosophy of Candy. You have to be yourself no matter what. I love that.

OTTENBERG: She was not lucky in love, but wow, the Roger Vadim gossip is amazing. Was that known before or is this your bombshell?

CARR: I had not known that before, no. I think they had sex one time, and I think it was not something that Candy wanted to repeat. But I think she thought, “Okay, it’s the casting couch and he’ll put me in a movie.” That was the approach there. But he was not interested in putting her in a movie. That’s when she was doing that play called The Reunion, where she plays a 70-year-old woman, which I don’t think she would’ve ever agreed to if she hadn’t thought that “Vadim is going to come and see me and he’ll see how great I am.” But the thing about Candy was that she constructed this persona, and it was really hard to get past that. She would not open up to many, and you can’t be intimate with someone if you don’t let them see inside. She was really cloaked most of the time. People did not get past that. So that would make it hard to have a truly intimate relationship with someone, I think. It’s sad. Other people, like Holly Woodlawn, for example, handled it differently. But Holly was like a devil-may-care kind of person, and Candy was not. When they were both working as secretaries somewhere in downtown Manhattan, Jeremiah told me Candy was very worried that she was going to be found out as not a cis woman. He said Holly, on the other hand, didn’t give a fuck. “Let them find out, I don’t care.” So that was a big difference between Candy and Holly. Candy would not have wanted that to be known.

OTTENBERG: Both your book and Beautiful Darling nail the frustration and despair of being admired, but never quite achieving the validation that comes with financial and mainstream success. Being adored, but having a sense of emptiness and loss that’s so profound. Candy’s depression is so relatable.

CARR: Yeah, and most people never knew about it. She was writing stuff in her journal that reads almost as a death wish.

OTTENBERG: I wrote this down from her journal: “I am suffering again. Desperately desire lover. Want to please a man. Despise my body. Will appeal to God to help me.” Who can’t relate to that in some way? What creative person can’t relate to a lot of her trials in New York City?

CARR: I did speak to someone who was a pretty good friend of hers about the Lou Reed song. “Candy says, ‘I’ve come to hate my body. And all that it requires.’” The friend said, “Oh, she didn’t hate her body.” I said, “Well, she wrote it down. It’s in her journal.” It’s a refrain that constantly comes up. Even though she’s beautiful, “Am I beautiful enough? Am I feminine enough?” This kind of thing was coming up in her personal writing all the time, right from the start. There’s this part of her where she’s so confident, but underneath it all, no, she really isn’t. And that part, she does not let people see. There’s the grandiosity, and then the flip side of it is all the uncertainty that was always there.

OTTENBERG: The creation of Candy is a mood board of Old Hollywood. Do you recall any of the specific references of movies that really created the voice, the look?

CARR: Her favorite movie was Picnic with Kim Novak. And she loved Kim Novak, she was her favorite actress. I put this at the end when she did that interview with Julie Baumgold, she explained it really well. Let me just find that. Hang on.

OTTENBERG: Of course.

CARR: She said to Julie Baumgold about Kim Novak, “There was always something frozen about her. She had to squeeze it all out. She was so scared, and that’s the way I was all my life. Everyone always told me I was beautiful, but I felt frozen, just like Kim. There was always something wrong with her, something slightly unacceptable.” It’s also interesting that she told Julie Baumgold that she identified with the lead character in I Passed for White, a film that I know falls into the kind of “tragic mulatto” category. But for Candy, it was about having a core identity that she often had to keep secret.

OTTENBERG: What was the biggest surprise that you learned about Candy?

CARR: Candy believed in god, but she had been raised Catholic and she wasn’t going to be a Catholic now that she wasn’t going to be accepted there. She started going into all these, what I call metaphysical sort of approaches to religion, where it’s about mind over body, and that’s at the core of what Christian Science is. And the Mary Baker Eddy approach, I guess, was the closest to what she really wanted. But I was amazed by that, that she was on this kind of spiritual quest through her life. I think that’s another part of Candy that no one was aware of.

OTTENBERG: As far as writing goes, is editing all of the material down excruciating? Is that the fun part? Because what I love about the book is the detail. You’ve got Candy’s birthday party in 1970 where Jackie smears the cake and there’s drama. If you’re into that stuff, it’s there. But is that just a talent you learn over time, writing these detailed biographies, of what to put in?

CARR: That moment, to me, says so much about Jackie also. But yes, it’s important to me to put in that kind of detail to really bring out who the characters are and what the scene was. I think it’s crucial.

OTTENBERG: What do you think was peak Candy?

CARR: I’d say that the year would be 1972, when she’s in that picture in Vogue. Women in Revolt is opening. She goes into the Tennessee Williams play. She’s on the cover of After Dark. The Death of Maria Malibran, the Schroeter movie, opens at the New York Film Festival. That’s sort of a peak year for her. And in ’73, she’s in The White Whore and Bit Player, the Tom Eyen play, but she’s starting to get sick. You can see that, even though she doesn’t talk about it very much. Then she opens at Le Jardin in June, and that’s not exactly a success. That appearance there where she’s doing Cabaret doesn’t exactly work. And by September, she’s in the hospital. So ’72 is really a peak year, lots of Candy stuff is in the air.

OTTENBERG: One last question. There’s a lot of descriptions of photography in the book. Is there one particular picture that you feel like she’s the most seen in?

CARR: I really like the Laura Rubin picture. I made a Xerox, I’ve got it hanging on my wall here, of Candy on the beach looking like a mermaid washed up on the shore. There’s also a Peter Beard one. Those are my two favorites. But there are tons of pictures of her out there, as you know. And there are some that haven’t been seen very much. Anton Perich has some interesting ones. But those are her pictures with Warhol.

OTTENBERG: I like the Cecil Beaton one where she’s smiling. When we were going through pictures for this story, the one you’ve got blown up on your wall is the one we’re going to blow up the biggest because she looks really beautiful, like a doll of today. She looks like Candy Darling, but she seems relatable in a way that is still very glamorous and cool. Thank you so much for talking to Interview about the book. People are going to love it.

CARR: You know, she interviewed for Interview. She did those interviews and was interviewed by Interview herself, so I think it’s totally right to be here.

OTTENBERG: The book, the specifics are such a gift. I mean it.

CARR: Well thank you, I really appreciate it.