RIOT GRRRL

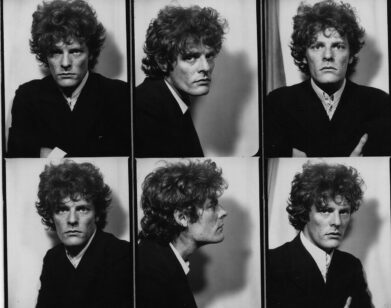

“We’re Trauma Bonding”: Kathleen Hanna, In Conversation With Brontez Purnell

“You know what they say about feminist art, right?” says Kathleen Hanna, “It’s not real—it’s just therapy!” Underneath this very bold statement sits a plain-as-day fact: which is that, honey, therapy actually works. And Hanna has been all of our punk rock therapist and father figure for close to four decades now. I think it should be known that Hanna has the same birthday as Charles Manson, but as a cult leader, she used her powers for good, being the often unwilling but nevertheless steady figurehead for the Riot Grrrl movement.

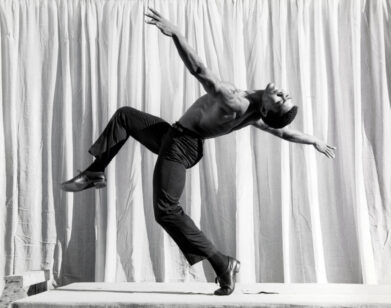

I remember being a gay bullied teen in the 90s (I know, who wasn’t?) and getting ahold of a Kathleen Hanna zine in which she explained that “being told that you’re a piece of shit and not believing it is a form of resistance.” I read that and have basically been an unstoppable cunt ever since. From the center of her message always seemed to stand the point that feminism and punk rock weren’t just political movements, but also, and perhaps more importantly, personal revolutions; a running archive of self-manifesting as a line in the sand, forever erasing and redrawing itself, and thank god. Hanna has always been a shapeshifter, staring as a photographer and visual artist, moving from Bikini Kill to her electropop solo persona “Julie Ruin” to Le Tigre and back again.

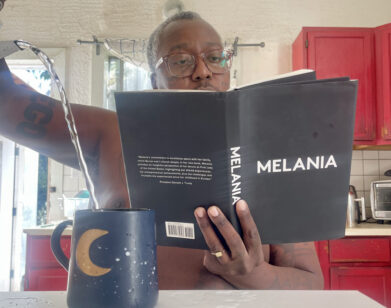

In this interview we talk about her new book Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, out today, a potent, revelatory, often bloody and heartbreaking but all in all triumphant rock-and-roll memoir. It sets a new bar for honesty in the form, like a good mix between Billie Holiday’s “Lady Sings The Blues” backed with Henry Rollins’ “Get In the Van.” History, as it does for most unwilling figureheads, has all but distorted, embellished, and even fictionalized her narrative. But she will have the final say on what her life’s been like. Here, we talk about the statement of vindication that is Rebel Girl.

———

BRONTEZ PURNELL: What’s up, dear? How are you?

KATHLEEN HANNA: I’m good. How are you?

PURNELL: I’m in L.A. for an art talk. They hired me to talk to a sculptor. Sculpture’s kinda hard for me, so I’m sitting here making sure I don’t sound like a complete dumb bitch.

HANNA: I’m going to try to make it. Sounds fun.

PURNELL: Oh my god.

HANNA: Why don’t you tell me these things in advance? I know, ‘cause I’m the same way. I don’t tell anybody shit until I’m already there. I can’t remember anything these days.

PURNELL: My friends are already so busy and I feel like I’m bothering people at this point. It’s been 20 years of, “Hey, can you make it to this show?” So let me ask you first if there’s anything you don’t want to talk about…

HANNA: Ask me anything. That’s the whole point. I wrote about everything, so you can ask me anything.

PURNELL: I’ll start by asking this. You wrote about something close to 48 years of history at once. Congratulations, that’s a fucking feat. Where did you start?

HANNA: I started how I usually start: I typed out a bunch of titles. One of the first things I typed was “Tip of the Sister Iceberg” because I was like, “What are the most important moments of my life?” I put it in chronological order after I wrote it because it was just an easier way for readers to follow the story. I’m not skilled enough to be jumping back and forth that much yet. But I started with a list of titles that were placeholders for what I have in my head, and then every day I’d look at one and I would write about that.

PURNELL: I’ve talked about this in writing classes with people, about how memory is this weird archeological dig, and it’s very fragmented. I noticed that in some of the book, there’s a lot of memoir that’s very factual, but the stories that feel more challenging do move between the performances. Let me say it like this: The miscarriage and the abortion chapter are the ones that I laughed at the hardest, and I really appreciated that. How did you protect yourself and where did you take the breaks?

HANNA: I started doing therapy. I got diagnosed with C-PTSD and I started doing trauma therapy.

PURNELL: Wait, what? You? I couldn’t imagine.

HANNA: Good one. Insert laughter here. Yeah, you too. I’m sure you’re just on a unicycle with your clown nose rolling around town, laughing your ass off.

PURNELL: In here I am.

HANNA: All of the titles I chose were the ones that were the hardest shit to tell. I started there because for some reason that seemed easiest. I was writing about the worst moments of my life right away, and I almost had a nervous breakdown a bunch of times. I had sushi with my agent and I was like, “Hey, I’m taking a couple months away from this to just do therapy because I can’t anymore. I’m crying every day, I can’t talk to anybody.” I took huge breaks and then I barely wrote during COVID because I found myself incredibly boring. Everyone’s dying and I was like, “I can’t possibly write about myself right now.” It felt pukey. But what was fascinating to me was, while it was painful to write about the traumatic stuff, it was easy to access those memories, to go back viscerally to those places and feel the feelings and cry and feel totally nuts for a week after. I had to go back to the happy memories and pull that out of myself more than the traumatic shit. That’s what made me realize that I’m not comfortable in happiness, and happiness scares me. I always was dwelling on the horrible things that happened to me because I never processed them. I kept moving from project to project and thing to thing and helping somebody else instead of helping myself. Like, “Oh, I’ll just watch a video by Gabor Mate about trauma and I’ll be fine.” He’s sexy. I have a celebrity crush finally, after 20 years of no celebrity crushes. And it’s someone who writes books about trauma. That’s sad.

PURNELL: In terms of celebrity crushes, you’ve got the ultimate husband.

HANNA: Well, that’s the thing. I married my celebrity crush.

PURNELL: Also, he’s just a genius, right? But to go back to what you were saying, I knew I was going to get into some three-ring process circle with you, and I was trying not to–

HANNA: We’re trauma bonding. When we are writing our album, “Trauma Bonding?”

PURNELL: Oh my god.

HANNA: “Trauma Bonding in Fast Motion.” Sorry.

PURNELL: It’s only trauma bonding if we’re recreating the bad pattern we learned from parents or lovers. What you were saying before about only remembering the bad things, I was just talking about this because I ruminate on the past a lot. They say it’s part of this caveman brain thing where we live a life of defense. It’s like being a deer in the Serengeti. You can only concentrate on the things that can hurt you to keep yourself alive because if you sit in a field too happy for too long, that’s when the lion comes up. When I was writing my book, there was a picture of me and my mom and my sister right before church, and my step-dad wasn’t there, and I was like, “Oh, wait, there were happy times.” It’s just hard to remember them because they’re not the things that will keep you alive in the immediate.

HANNA: Well, it’s really hard to go there if you haven’t processed the trauma. I’m so sick of talking about trauma, you know what I mean? But I am trying to be specific about things because I feel like my brain universalized everything to be like, “Everything’s trying to kill you.” And especially when you’re betrayed by very close friends and family members and people who were supposed to be taking care of you, you start attaching family and love and food and everything to trauma. So when I’m having a family experience that isn’t traumatic, I’m fucking confused. Watching my kid, I’m seeing him be able to cry when he hears a song he loves. He said, “I’m a crier at school. People call me a baby.” I asked my mom, “Is it too early to play Cry-Baby with Johnny Depp?” You know, the John Waters movie? I was like, “He’s 10, I think he’s ready for that.”

PURNELL: I feel like that’s the age I started watching it. Well, we had no choice.

HANNA: Yeah, but we were also finger-fucking people in the woods when we were nine. The thing is, having conversations with regular people doesn’t make any sense to me because I’m like, “Oh yeah, I remember being 10 and noticing my neighbors were having a party in the basement, and that meant their kitchen wasn’t being protected.” And I was 10 and I was drinking out of my parents’ liquor cabinet, and I was like, “Ooh, if I want more liquor, I could go over.” My kid is 10 and he would never think to do that. I look at what his life is like and it’s so different. I’m trying not to be the opposite of my parents, because then I end up reinforcing them.

PURNELL: Oh, no. My mom being like, “Men are going to try to molest you because you have a fat ass,” and I was 10. Or a teacher being like, “You should read this,’ and it’s The Bell Jar and I’m 12. Going back to you calculating if the people are in the basement, you can steal the alcohol. You are a Scorpio, right?

HANNA: Yes.

PURNELL: And you have the same birthday as Charles Manson?

HANNA: Yes. We also sing and play guitar badly, so I have that going for me. Wait, who’s your celebrity birthday twin?

PURNELL: Silvia Ray Rivera and Lindsay Lohan and the guy from Curb Your Enthusiasm.

HANNA: That’s all I need.

PURNELL: Yeah. Makes sense. I was going to ask you how you feel being a Scorpio has affected your art career, but I don’t want to fucking put you through that. But this is also what I want to say. Beyond that pesky feminism thing and your leader status, there is a significant portion of your book where you are writing about this bygone culture of kids hopping in vans and making music. And Bikini Kill, y’all had this weird thing where your name was everywhere, but it didn’t really translate to money in the same way. Do you feel like now that y’all are touring that you’re finally getting your flowers from that time and all the fucking shit that y’all had to go through? All the abuse and all the unfairness?

HANNA: Yes, definitely. When I left Bikini Kill, I wasn’t in a good place. It was not a good band for me to be in. I was physically and emotionally exhausted, and the way people treated us was absolutely obscene. So now to go on tour with Bikini Kill, to be older and able to have real conversations with my bandmates and to be able to turn lemons into lemonade and make jokes about the fucked up shit like, “Remember that time when that guy spit a beer in your face?” That is really healing and awesome. Also, to have the support of having an actual crew and having the basic things you need to work. We still do have fucked up shit happen on tour like everybody, and we’re still exhausted and all that, but it’s almost like being in a normal band. I’m having that experience of not getting treated like total garbage all the time, and to be able to do it with two people who were also treated like garbage next to me for years and years. And we let our relationships go to shit because we were constantly fighting the outside world. But now we’re able to look at each other and be like, “Hey, how’s it going today?” And I can say, “I need to cry before this show.” Or I tell them, “I’m remembering this time when this happened and I need to talk about it.” Or my voice teacher was murdered, and that comes up a lot because I’ll be having a hard day with her death, and I’ll talk to them about it. I never could do that in the nineties. So now I feel like I’m getting some rich person spa healing treatment by going on tour with Bikini Kill.

PURNELL: Another thing I wanted to ask is, I feel like now music becomes exponentially harder. The idea of even pushing an amp, the idea of playing for a group of punk rockers. I’m only 42, I have nothing to complain about, but sometimes I’ll be thinking, “Well, there’s Kathleen, there’s Toby, there’s all these other people still doing it.” Where do you find the energy? Also, given physical histories, illnesses, your drive to keep going is remarkable.

HANNA: I’ve wanted to sing since I was a little kid. That was my safe place from my dad. I would go in the basement and listen to records. I would make up dances and sing to Kenny Rogers and the First Edition. All day at school I would be staring off into space, thinking about the routine I was going to do. We moved a lot, and my dad hated me and was mean to me. So it was like I had this thing that was mine and it was the place that I went for joy. I was sick for a really long time and I was bedridden, it was awful. Not being able to perform told me I really wanted to and really needed it as a person, as an outlet.

PURNELL: Yes. And I wanted to ask you about the future. Do you see more writing? I was reading this and thinking it would be really funny if there was, I don’t know, a history biopic or a murder mystery noir written by you.

HANNA: I do want to know what the sequel should be. What would be the next book be?

PURNELL: Well, the thing about the memoir that’s really funny is, some people say that memoir is fiction in a way, because when you remember something, you’re not just remembering it, you’re remembering the last time you remembered it and the time before you remembered it.

HANNA: Or the photograph you saw of it.

PURNELL: Totally.

HANNA: I wrote a novel that I didn’t finish. It’s probably really bad. I wrote it when I had Lyme disease, because I had to have something to do while I was slobbering in bed. It was about this girl who was kidnapped by her uncle and sexually assaulted for two weeks. It was pre-internet, so it was like a “baby Jessica falling down the well” type of story where the whole nation was looking for her. Then they made a movie of it, and it’s about that girl going to college and trying to be incognito, and then someone sees the made-for-TV movie about it and puts two and two together. And then that woman becomes obsessed with her story and starts one-upping her. It’s all about the thing like, being so attached to this Riot Grrrl thing, but not making any money. Everywhere you go, you have this one little catchphrase, but you’re not making any money off it, and your life is fucked. I always relate to those people who get internet famous and then they don’t make any money off it, because I feel like that’s what happened to me. It’s a terrible novel. I should have never even mentioned it.

PURNELL: No, you need to finish that shit. I’ll read it right now.

HANNA: But again, it’s about dealing with family stuff that you can never say aloud.

PURNELL: Oh, for sure. Fuck them. Is there anything else you’d like to add before we go?

HANNA: Just I hope I get to see you tonight.

PURNELL: It’s near West Adams.

HANNA: I don’t know where that is because I drive places by my navigation. I hope I will make it because I would love to see you in person and listen to you talk. And you don’t even have to say hi to me, I’ll just be there masturbating in the back–

PURNELL: Oh my god, you sound like an old client of mine.