LIT

Walt John Pearce and Honor Levy on Potties, Performance Art, and Gertrude Stein

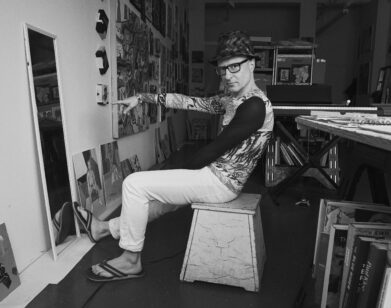

Walt John Pearce and Honor Levy in Walmart.

Writer Walt John Pearce is a big fan of big books. This weekend, he’s trading his usual reading spot, a rocking chair on his mountain-side porch, for a new project space in downtown Manhattan, and inviting others to join him. In an effort to turn our love of literature into a shared experience, he and Sam Frank have organized a nonstop marathon reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans. Ex-podcast-co-host Honor Levy checked in on Walt a few days before he made the trip down to the city. In his local Walmart, she found him purchasing supplies that will help him survive the upcoming 52-hour-long reading. Honor, whose first book My First Book comes out on May 14th, talks to Walt about roses, commas, and making friends through literature.

———

WALT JOHN PEARCE: Okay. Where are we?

HONOR LEVY: Yes. Where are we?

PEARCE: We’re in the sleeping bag aisle of Walmart in [REDACTED] New York.

LEVY: And what are you buying, your sleeping bag? What are you buying the sleeping bag for?

PEARCE: Well, we’re both buying sleeping bags. We’re both buying sleeping bags to sleep in Earth.

LEVY: On Earth.

PEARCE: In Earth, the name of the space where we’re hosting a 52 hour marathon reading of Gertrude Stein‘s fabulous book, The Making of Americans.

LEVY: And what inspired you to want to do this reading?

PEARCE: I’ve been really into happenings and performance art.

LEVY: You have been into performance art?

PEARCE: No, I’m just kidding.

LEVY: Feminist performance art?

PEARCE: I’m just kidding. I like Gertrude Stein.

LEVY: Have you read this book before?

PEARCE: I’ve read about three-fourths of it, but not in order. I like Geography and Plays. That’s my favorite Gertrude Stein book. Lucy Church Amiably is also good, and Three Lives is good as the most readable in a traditional way. But then I was googling her, and I saw that Paula Cooper Gallery back in the day used to do these every year on New Year’s Eve and I was like, “Wow, that’s an awesome idea.” Then, I saw that Sam Frank and Triple Canopy did it 10 years ago, and I said, “Wow.” So now Sam Frank is helping me. And that is that. And Paula Cooper herself is reading as well.

LEVY: Wow.

Walt John Pearce at Walmart in upstate New York.

PEARCE: Do you think we need this giant knife or the huge canteen or anything for the reading?

LEVY: Maybe to put soup in? Are there going to be snacks?

PEARCE: Yeah, I think we’ll have coffee and doughnuts maybe. Oh, there’s tea. Dean Kissick chose some English Breakfast for us, I believe.

LEVY: Nice. And what about the book?

PEARCE: What about the book?

LEVY: What about the book makes it—

PEARCE: American?

LEVY: No. What started this tradition?

PEARCE: I don’t know. I wasn’t there, but people call it unreadable. And it’s very rhythmic.

LEVY: So it’s good to read.

PEARCE: I think it kind of puts you in a trance a bit. So it’s a perfect book to read out loud for 52 hours or really any amount of hours, but ideally around 52.

LEVY: And how did you choose the different people to come and read? And did you choose sections?

PEARCE: No, there’s no sections because every reader will read for 20 minutes, so it’s impossible to predict exactly what you’ll be reading. Me and Sam Frank just made a big brainstorming list of people that were like—I like this event because I think it’s a very—I’d say it’s unifying. It’s just a nice event for literature and for—oh, what is that?

LEVY: It’s a potty for babies.

PEARCE: But what do you do when you have to empty that thing?

LEVY: I’m not sure, but it’s like a real replica miniature toilet with a realistic flushing sound. Wait. [Sound of flushing].

PEARCE: Kind of realistic. It’s a little cartoonish.

LEVY: Yeah.

PEARCE: What was I saying?

LEVY: How you chose the readers. How it’s a unifying thing.

PEARCE: Oh yeah. Well I think it’s a nice unifying event. We have cool old Language poets and, like, Fluxus people, weird downtown socialites, losers, writers, prolific writers, weird writers, good writers, bad writers, personalities, hermits. We have a little of everything.

LEVY: And we’re going to stay the whole time, yeah?

PEARCE: I’m personally going to stay the whole time. Yes.

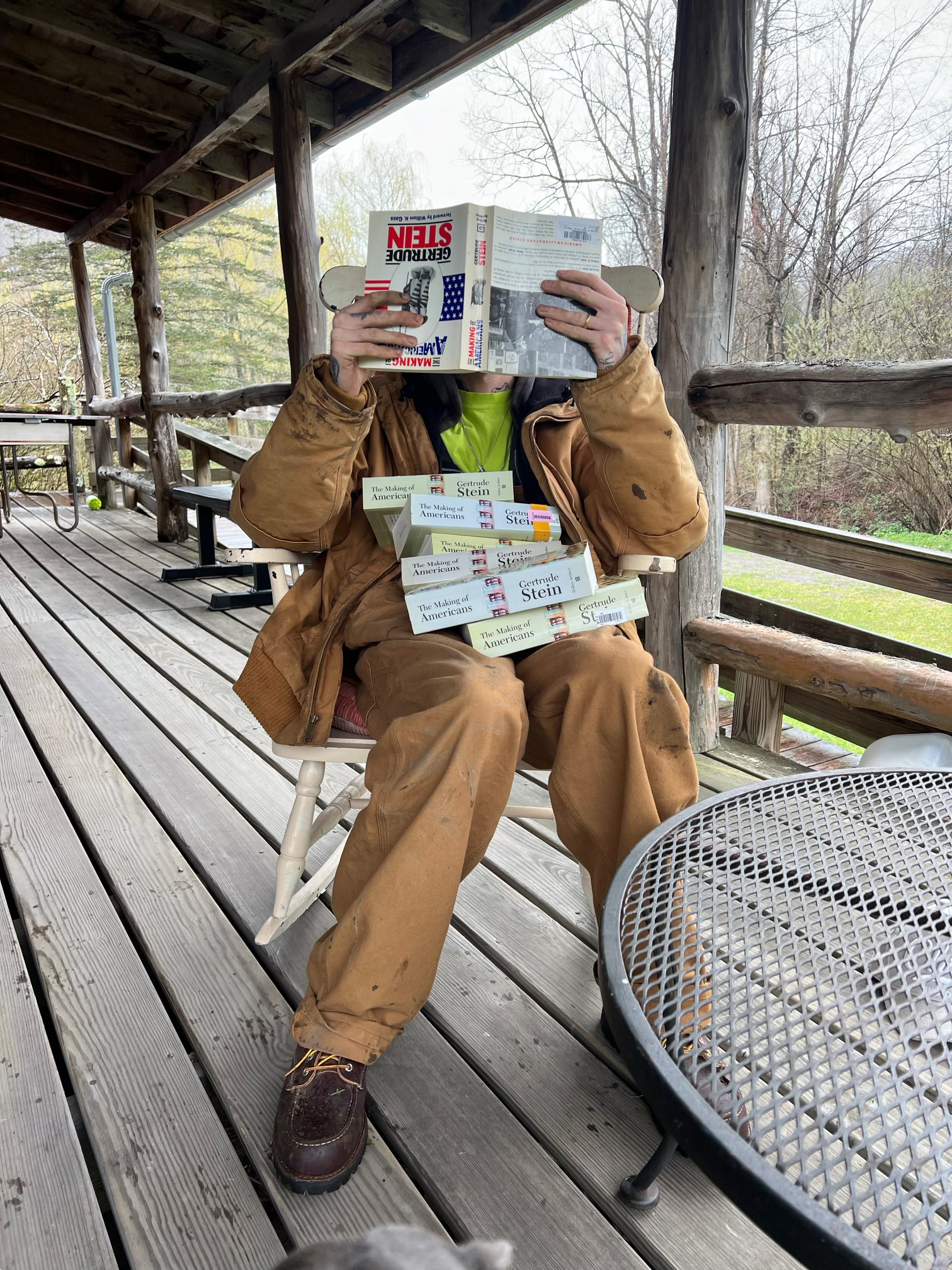

Walter John Pearce on his porch in upstate New York

PEARCE: Now, we’re in my study. We’re home from Walmart. I have to keep a big box to block the door from Freedom. So here’s one, two—

LEVY: That’s the name of the dog?

PEARCE: Three, four—yeah, Freedom’s the name of the dog. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight copies of The Making of Americans. I mailed one to Lydia Davis overnight shipping yesterday to make sure she had a copy for her reading because she actually had an abridged version.

LEVY: Oh, wow. Is that common with these Gertrude Stein books?

PEARCE: Before 1966 you couldn’t really get this text at all except for an abridged version, which is the one that Lydia had. In 1966 they put out the full version for the first time, and then Dalkey has continued to semi keep it in print, as Dalkey tends to do, for the last 30 years. That’s the version we will be using and it clocks in at 925 pages.

LEVY: Wow.

PEARCE: I think that Gertrude Stein is probably objectively one of the most important modernist writers and also—

LEVY: What’s modernist writer mean?

PEARCE: In a just literal sense of the modernists, per se.

LEVY: Right. Okay. Yeah.

PEARCE: There’s hundreds of pages in The Making of Americans where it’s basically 40 words total or whatever, just used in different ways over and over and over again. They’re not complicated words, but it becomes a very complicated text. I think part of the reason why she does not get the credit that other modernists like Joyce or something would get is because—

LEVY: She’s a woman.

PEARCE: Yeah, she’s a woman and she’s a Jew.

LEVY: And she’s Jewish.

PEARCE: Also her work was simply not accessible, both in the sense that I think it was kind of highbrow and also made fun of by the press. Because she was a well-known figure, her writing was not taken particularly seriously. For me the reason Stein is so important is that rhythmically it really blew things open. Coming from a writing point of view I used to like really really long sentences and I still do but I used to like long sentences with commas and Gertrude Stein called commas positively degrading which I actually agree with. I think a comma is a cheat in many ways, and if you can find a way around it, you should.

LEVY: We have to print this paragraph with no commas.

PEARCE: There should be no commas in this whole interview. I interviewed somebody for Interview a couple of weeks ago, and I removed all of the commas. [Ed note: we put the commas back in].

LEVY: This is getting too meta. You’re saying a comma is positively degrading.

PEARCE: Oh, yeah. They’re positively degrading. Gertrude Stein, when she uses a comma, it hits because she earns it. The best example I can think of earning a comma is Ezra Pound’s translation of Catullus when he says, “I hate and I love. Why? You may ask but / It beats me. I feel it done to me, and ache.” When a comma is really earned, you can feel it. Cheap writing comes from too many commas. I would rather read an “and” than a comma almost any day, and I would almost always rather write an “and” than a comma.

LEVY: But you don’t say “and” out loud when you’re speaking.

PEARCE: These rules are also meant to be broken, of course. But first, somebody had to break them, and that was Miss Gertrude Stein. It’s also remarkable how early on this stuff was.

LEVY: What year was this book written?

PEARCE: 1911, but she started it in 1903.

LEVY: I need commas.

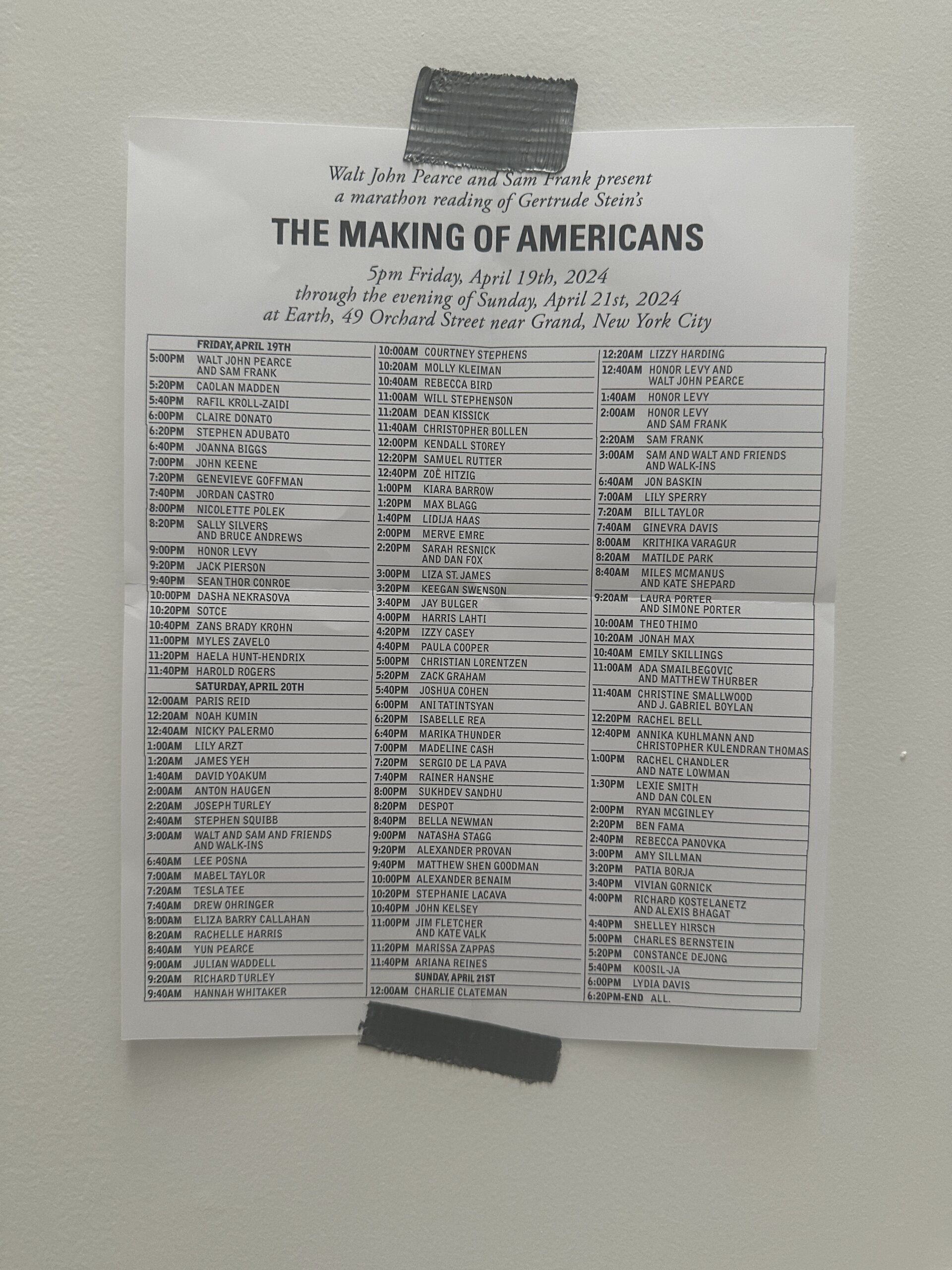

Making of Americans line-up at Earth.

PEARCE: Another interesting thing about her is that everyone loved The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Stanzas in Meditation came out at about the same time, which is the opposite style. It’s a very normal book in a way, and it caused the press to say that she’s joking and making fun of you in her other work.

LEVY: For not understanding?

PEARCE: No, no, that she actually is a really good writer and all this other stuff she’s putting out is a prank. But she did not believe that at all. She would say things like, “Everything I’ve written I mean exactly as I’ve written it.” One of my favorite quotes of hers is her response to someone asking about, “Rose is rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” I think it must be from an interview, but they ask her about it, and she says, “Listen, I’m not an idiot. I know people don’t talk like that in real life.” But not in the last 100 years has the rose looked so red in English poetry.

LEVY: What’s that mean?

PEARCE: She’s saying she knows people don’t say, “And a, and a, and a, and a, and a, and a, and a,” but the fact that she did it makes the rose—

LEVY: Even redder?

PEARCE: As fragrant as it could ever be in poetry.

LEVY: Wow. That’s cool. Got any other favorite quotes?

PEARCE: Of Stein? Yeah, let me get my phone. There’s a good one about romanticism. Do you like romanticism, Honor?

LEVY: Like the romantic poets?

PEARCE: Yeah.

LEVY: Like Keats and Shelley and stuff?

PEARCE: Yeah.

LEVY: Yeah. I don’t know any of the terms, I don’t know what postmodern means. I don’t know what modern—

PEARCE: It doesn’t mean anything. I know what modernism is, I think.

LEVY: Yeah, I know.

PEARCE: Postmodernism I usually just call New American modernism because it’s all just American guys that wrote big books.

LEVY: Who are you talking to about this stuff?

PEARCE: I’ve been meeting a lot of really cool people lately who actually love to talk about this stuff. Through this event, too. It’s so fun when people respond and they say, “Oh, I love this Gertrude Stein quote.” And I say, “Wow, that’s so cool. I also have Gertrude Stein quotes that I love myself.” Anyway, you like romanticism, Honor? Keats, Yeats?

LEVY: Yeah. That’s different.

PEARCE: Keats, Yeats?

LEVY: They’re totally different. Yeats.

PEARCE: Yeats? Yeats?

LEVY: Yeats. Okay. Well, are you doing a Gertrude Stein thing, repeating stuff?

PEARCE: No, Yeat like the rapper.

LEVY: Oh, Yeat.

PEARCE: Yeat.

LEVY: You should have invited him to read.

PEARCE: Here’s Gertrude Stein on romanticism. “Romanticism is then when everything being alike everything is naturally simply different, and romanticism.”

LEVY: That’s great. Should we end there?

PEARCE: I guess. Did we say enough? Did we even say anything?

LEVY: I feel like we did. I don’t know. I have no idea.

PEARCE: Me neither. Do we ever say anything?

LEVY: No. When you and I get yapping, we don’t say anything.

Walt John Pearce and Sam Frank present a marathon reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans. 5pm Friday, April 19th, 2024 through the evening of Sunday, April 21st, 2024 at Earth, 49 Orchard Street near Grand, New York City.