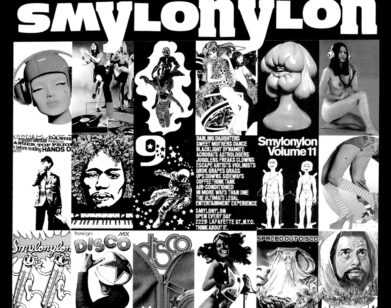

Walt Cassidy Walks Us Through the Wild Glamorama of New York City’s Club Kids

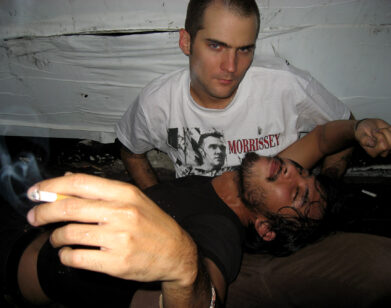

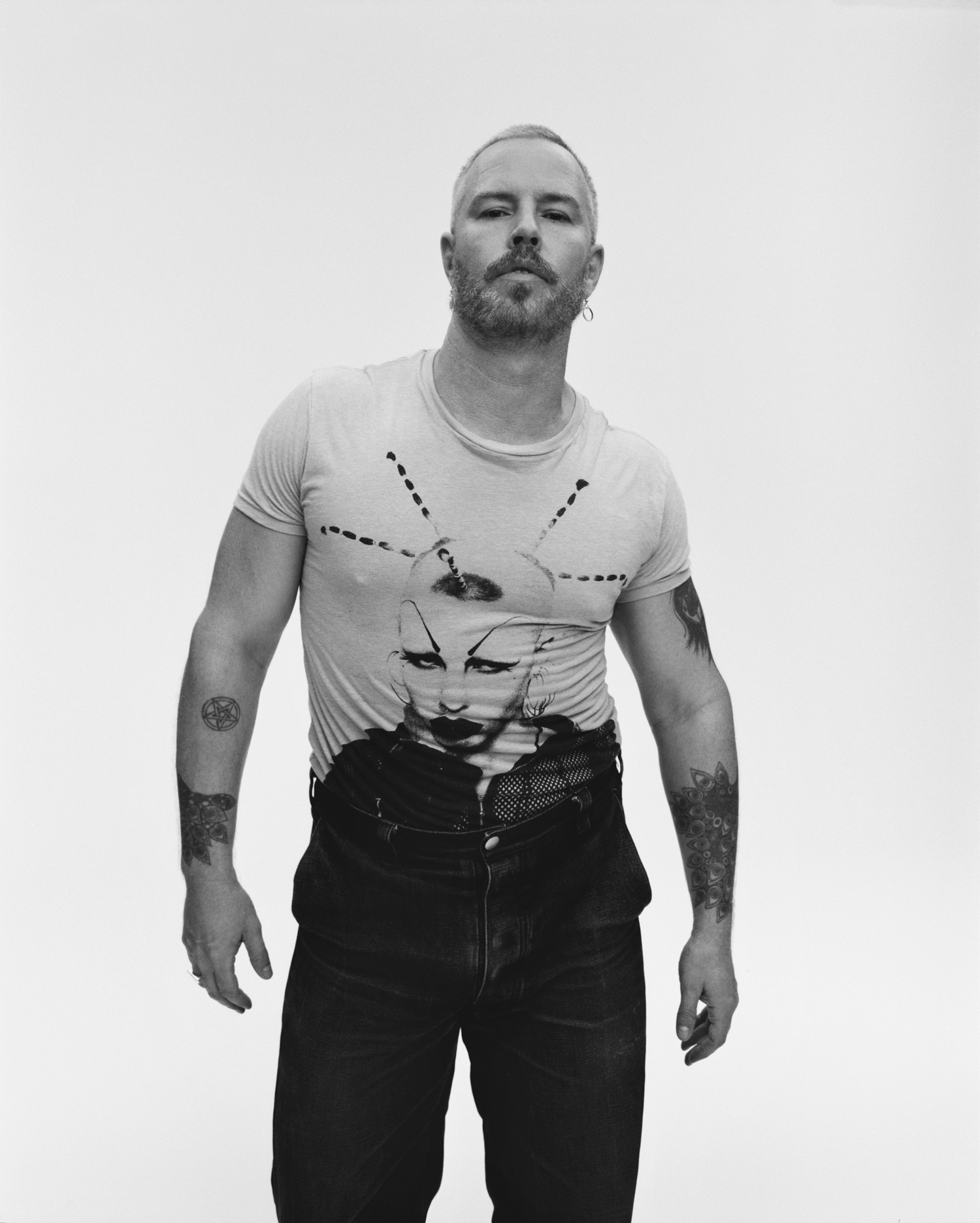

T-Shirt, Jeans, Earrings, and Ring by WALT CASSIDY STUDIO.

Every era has its outrageous subcultural scene, and in New York in the 1990s that mantle indisputably belonged to the Club Kids. Known for, among other things, their deliciously cartoonish, gender-indifferent costumes (teetering on mile-high platform shoes) and their reign over downtown mega-clubs such as the Tunnel and the Limelight, the Club Kids did more than just fill the nightlife vacuum left behind after the death of Andy Warhol. They also brought a wild, joyous, youthful levity to the city through the ongoing darkness of AIDS and offered a far more inclusive and democratic, less elitist conception of the social “it” hierarchy, where creativity mattered more than cash flow. It was the perfect glittery storm of an alternative underground, commingling with techno, grunge, rave, and drag cultures. The vast warehouses of the pre-Giuliani West Side and the still-affordable rooms of the Chelsea Hotel proved the perfect playgrounds.

The main thrust of the Club Kid movement ran from 1988 to 1996. Walt Cassidy (soon to be known as Waltpaper) arrived in New York in 1990 as a student at the School of Visual Arts. It wasn’t long before he climbed the ranks and became one of the key personalities of the scene (hosting the parties, promoting their strange-is-better ethos, and, of course, getting his photo taken in all of his many extremist homemade guises). This October, Cassidy puts out his long-gestating tome dedicated to the radical spirit and wild glamorama of that unruly, candy-colored decade. Entitled New York: Club Kids (Damiani), available for pre-order now, the project is as much a comprehensive record of the aims and attitude of the movement as it is “a love story to New York, because that’s the city that allowed me to find myself and be myself.”

For Cassidy, one of the essential functions of the book is to provide a corrective to the default association of the Club Kids with the 1996 murder of Andre “Angel” Melendez by Michael Alig. “I would say a lot of the community felt our experience of the time was hijacked by that ‘Party Monster’ narrative,” he says. “That’s not the New York I knew. That narrative doesn’t include the creativity, vibrancy, and cultural impact that I experienced.” Instead, Cassidy weaves a far more optimistic narrative where a bunch of misfits made a wonderland by being themselves. Here, the eternal Waltpaper discusses the scene through a series of photos.

———

Walt Cassidy, as his after-dark alter-ego Waltpaper, photographed by Michael Fazakerley in 1992.

“Before we would go to work at night at a club, we would often stop by Michael Fazakerley’s studio in Chelsea to have our looks documented. These photographs would be used for invitations, press photos, magazine shots, and publicity stills. Michael would do a headshot, a torso shot, and a full-length shot of each of us. Our nights were very structured. After being photographed, we’d either have an Outlaw party or there would be a dinner organized at the club before the night started—that was family time and we’d usually have a celebrity guest, someone like Joyce DeWitt from Three’s Company or Weezy [actress Isabel Sanford] from The Jeffersons. There we all were eating dinner off paper plates at the Limelight with someone we’d watched on television growing up. In this portrait, the tutu I have on is made out of window-screen netting, held up by dog chains and hardware bolts. It was my version of a baby-doll dress.”

———

Lil Keni’s platforms, photographed by Misa Martin in 1994.

“The ’80s were about collectible high fashion, but we would wear these completely throwaway ensembles. We’d wander the streets in the day collecting supplies, hot-glue them all together, wear it for a night until it fell apart, and then toss it. Everything between our head and feet was throwaway. But our shoes were like our names; they were reflections of our character. This is a shot of Lil Keni’s shoes. When we started doing platforms, we’d go to a place called Alex Shoe Repair on Second Avenue and 3rd Street. At first we used Dr. Martens, because boots are really easy to platform. In a way, it was like wearing mobile gogo-dancer boxes. But eventually we experimented with sneakers, which was not only lighter than boot rubber but also more colorful. It became not only about height, but also about dimension, and that’s how you could personalize your shoes.”

———

(From left) Reign Voltaire, Julie Jewels, Waltpaper, DJ Keoki, Sacred Boy, Björk, Keda, and Lil Keni, photographed by Michael Lavine in 1992.

“Björk came to our nights around the end of her band The Sugarcubes. Some of us Club Kids actually ended up onstage at the Sugarcubes’ concert at Roseland Ballroom in 1992. Björk was really interested in techno music, and in the early ’90s techno was starting to bubble to the surface at the mega-clubs and taking over nightlife. Looking back, it was natural that Björk gravitated toward our scene. We were really outrageous, and she fit right in.”

———

(From left) Astro Erle, Waltpaper, and Desi Monster, photographed by Tina Paul at Limelight in 1992.

“This is a photo of Astro Erle, me, and Desi Monster. We formed a trinity that could always be found on the main dance floor, in the belly of the beast with all the dancing boys, while many of the other primary Club Kids preferred to be tucked away in VIP lounges. We each offered different but complementary elements with our identities. Desi was the larger-than-life, friendly cuddle monster; Astro Erle was a futuristic cyber hellraiser; and I was the earthy faerie tribal witch doctor.”

———

Sacred Boy, photographed by SKID in 1992.

“This is Sacred Boy from an art exhibition in New York called Nocturnal Oddities at Willow Gallery in Soho in 1992. The Club Kids were on display as art objects. Sacred Boy was really into prosthetics and was a great makeup artist. He would juxtapose these violent images with this religious, Catholic School boy uniform. But this photograph illustrates that part of the charm of the Club Kids was that underneath all of the looks, we were really a bunch of cute boys and girls. Everyone was pretty attractive. A lot of us were also art students. That exhibition really showed off the range of creativity in the group. Desi and I staged a weird performance of an abortion, where Desi was the fetus and I was this Saint Sebastian–type figure.”

———

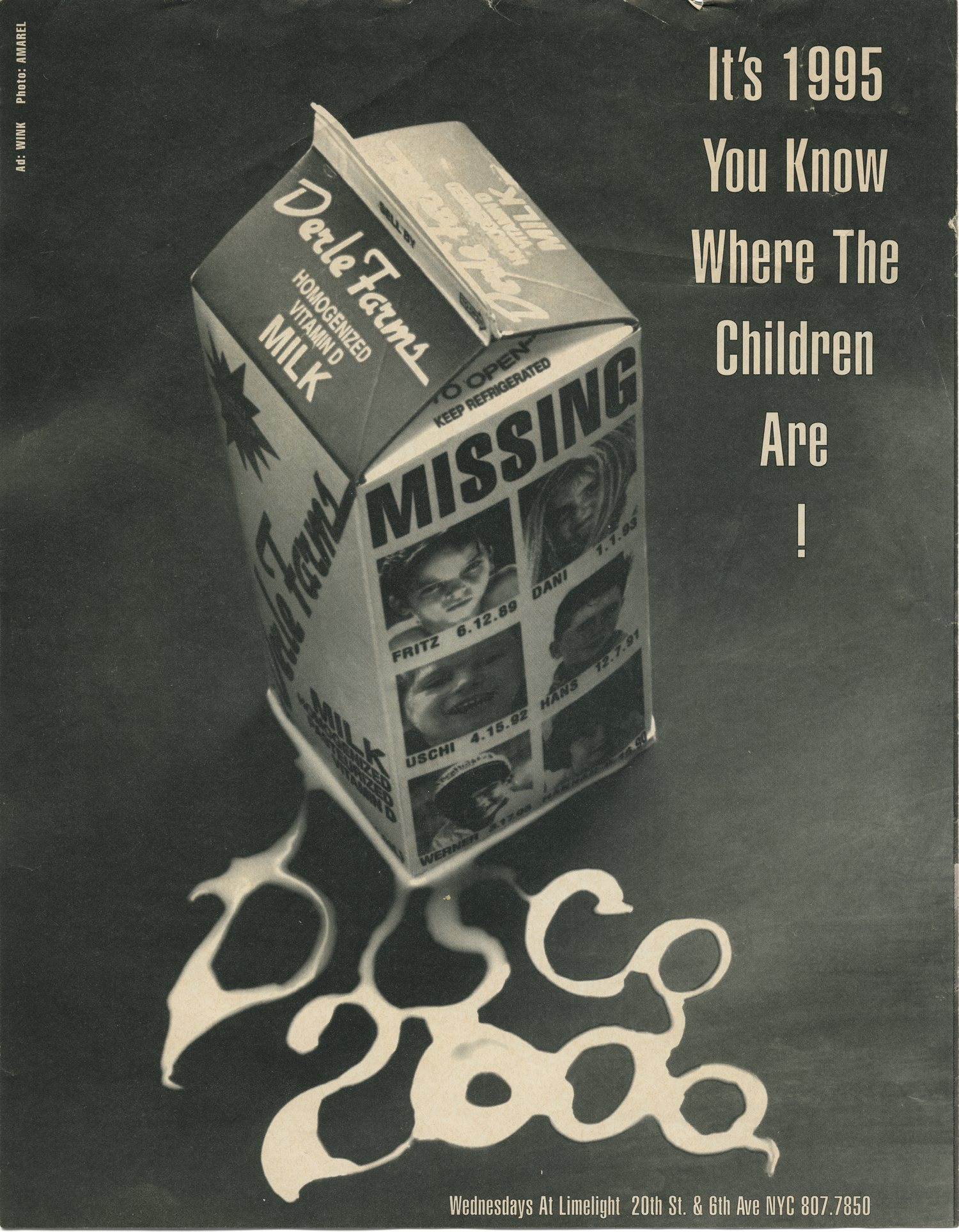

A Disco 2000 party flyer by Gregory Homs from 1995.

“This is a piece of art by Gregory Homs, who really created all the branding and visuals for the mega-clubs. He did the advertisements and promotional materials, and he designed the Club Kid trading cards. Disco 2000 was the quintessential Club Kid party. It was held at Limelight, Peter Gatien’s flagship. Disco 2000 was hugely successful and ran for a long time. This ad is riffing on the question for concerned parents that was in the culture at the time: ‘Do you know where your children are at night?’ It was a fun play on that idea.”

———

The crowd at Club USA, photographed by Tina Paul in 1992.

“Club USA was the pinnacle of the scene. It’s when the vision really gelled. Club USA was located in an old theater in Times Square. Its interior was designed by Eric Goode, who was behind clubs like Area. The décor was playing off of Times Square and American commercialism with an explosion of corporate logos and advertising. There was a mural of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese, and there were also VIP lounges designed by Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler. This was during the reign of the supermodels, so fashion was really peaking and there was always a strong fashion crowd here. It was also during the height of heroin chic, so there was a lot of heroin going on at the time. Club USA was the crescendo and it also marks the end. It had reached full blossom, and in many ways we had done everything we could do. We worked every look. We tried every drug.”

———

The Club Kids made many appearances on talk shows such as Geraldo, The Jane Whitney Show, The Richard Bey Show, The Joan Rivers Show, and The Phil Donahue Show.

“These are screen stills from many different talk shows of the era—Geraldo, The Phil Donahue Show, The Joan Rivers Show. The Club Kids not only laid the seeds for self-branding but also for reality television. We were all about accessibility. We wanted to be a part of the mainstream vernacular. We weren’t trying to stay obscure and hidden away in a club. We were aggressive about wanting to be a part of society. The talk show circuit became an avenue for opening up the conversation. We knew we were being shocking, but it was always peppered with humor and I think that’s what made us palatable to middle America. It was like, ‘Wow, there’s this really freaky group in New York, but they’re funny and witty.’ We weren’t an elitist movement. You could conceivably see us on one of these shows, come to New York, do a look, turn up at one of our clubs, get in, show up, and participate.”

———

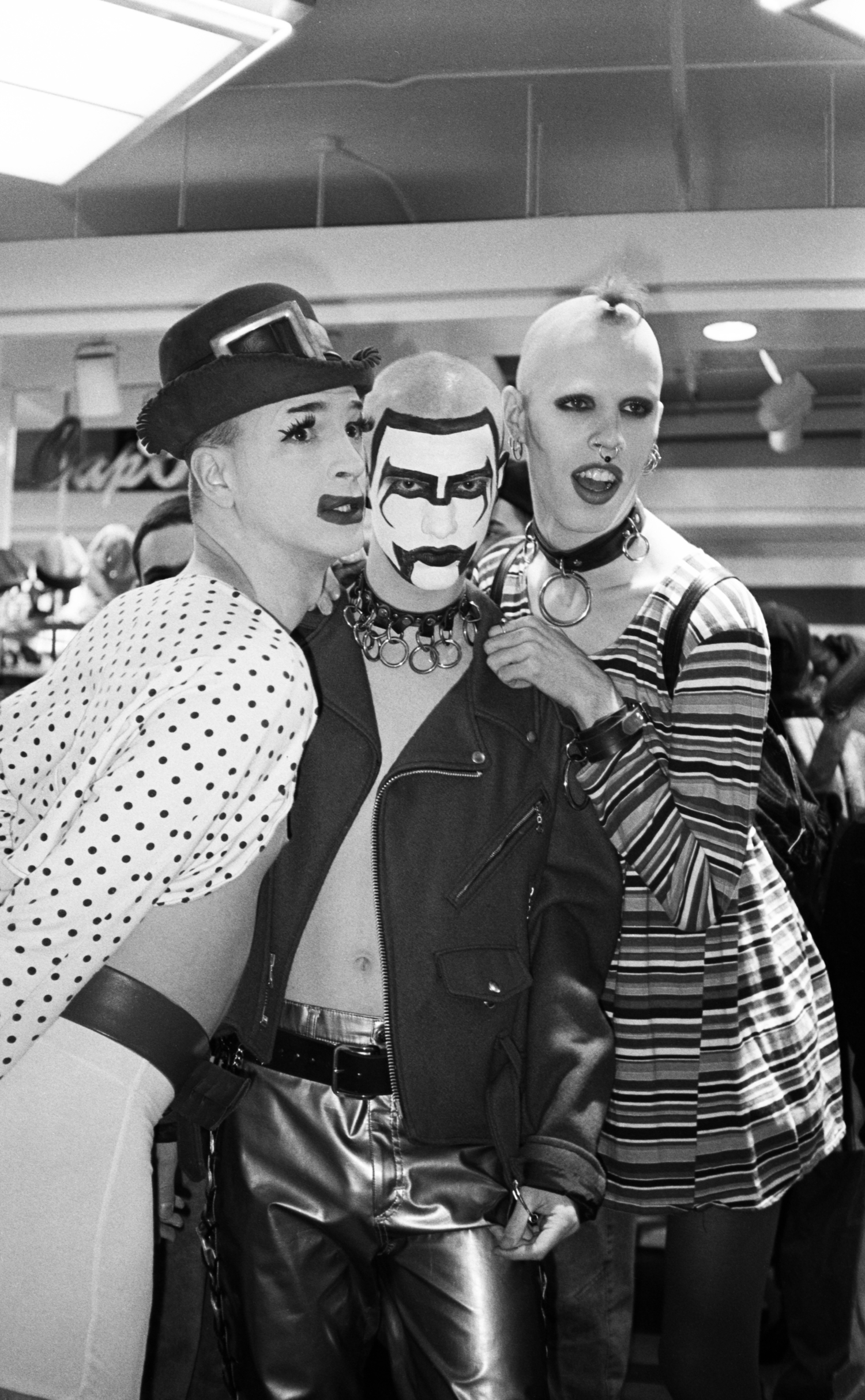

(From left) Michael Alig, Christopher Comp, and Waltpaper, photographed by Catherine McGann at a Macy’s rave in 1992.

“This is Michael Alig, Christopher Comp, and me at a Macy’s rave. The fact that we were throwing a party at Macy’s shows just how far we had made it into the mainstream. In a way, the Club Kids were like the Old Hollywood studio system. There was machinery around us—photographers, PR people, security—all out to promote our characters and protect us. I remember showing up at Macy’s and it was the first time people asked me for my autograph. Michael was obviously an essential part of the Club Kid movement. I wouldn’t want to erase him from the narrative. His vision and mentoring role was undeniable. He was a bit older than we were and he took care of us. He was never covetous of the spotlight. He wanted us to be presented as a group. There was definitely a pecking order, an inner circle, but Michael was all about the Club Kids as a family. I think his great sadness is that he ultimately brought so much pain and drama to the rest of us. I don’t think it was ever his intention to do that. To this day he’s still very protective of us. A lot of the time he had to protect us from himself.”

———

Chloë Sevigny, photographed by ZAK at the Chelsea Hotel in 1994.

“With the incoming rave scene, style boundaries began to soften into an ambiguous gender-fluid style, which melded references to Club Kids with skate, indie, hip-hop, and grunge. Fashion brands began casting ‘street models’ in shows and campaigns. I met Chloë [Sevigny] early on, and we modeled together in various editorials that showcased rave vs. Club Kid style. Back in the day, we would do random photo shoots for no reason other than to hang out and be creative. The photographer ZAK was living at the Chelsea Hotel, where I also resided during the ’90s. Chloë would stop by regularly and hang out. We had the balcony that held the famous neon sign, and we’d installed a giant white fiberglass pet lion named Leo. One day we had a stash of Valium, so we all popped a pill and decided to do a photo shoot. My roommate Johnna Davis styled Chloë from our closet, I did her makeup, and ZAK shot the pictures. While we did stuff like that for fun, we also knew that our lifestyles and identities articulated something special. We believed in ourselves, despite not knowing where our paths would eventually lead us.”

———

Grooming: Adam Markarian using Wella Professionals

Photography Assistants: Geoffrey Voight Leung and Stephen Wordie

Fashion Assistants: Malaika Crawford and Dominic Dopico

Special Thanks: Jack Studios