Wagner Moura and the Politics of Pablo Escobar

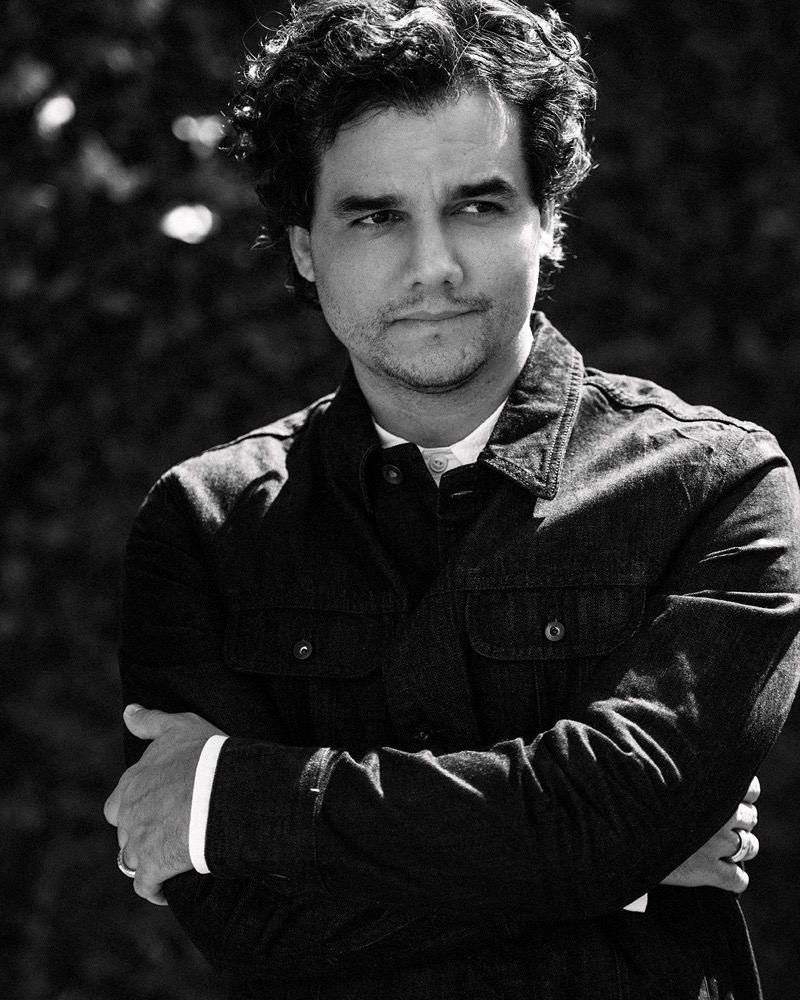

WAGNER MOURA IN LOS ANGELES, JULY 2015. PHOTOGRAPHY: BRIAN HIGBEE. STYLING: VAN VAN ALONSO. GROOMING: ANNA BERNABE FOR ART DEPARTMENT USING ORLANE SKINCARE AND LEONOR GREYL HAIRCARE.

Wagner Moura originally wanted to be a journalist. “When I thought about doing journalism, I thought I would do political stuff that would change the world. I would uncover corrupt people; I would send people to jail,” the Bahia, Brazil native explains. “[But] when I started to work at a newspaper, the kind of things I was sent to do were so not exciting. I was sent to talk to neighbors that were having a problem or the secretary of the mayor to understand why a street is blocked—things that I didn’t really care about.”

Instead, Moura became an actor. He started doing local theater for children and then moved on to Brazilian films and television dramas. In 2007, he was cast as Capitão Nascimento, the leader of a group of special-forces in Rio, in the drug war thriller Elite Squad. He was not, legend has it, supposed to be the film’s protagonist, but after wrapping, the director José Padilha re-edited the film around his performance. Elite Squad became a huge hit, and Moura one of Brazil’s biggest stars. A sequel, Elite Squad: The Enemy Within, followed three years later.

But Moura, who is now 39, never lost his interest in politics. He recently became a goodwill ambassador for the ILO (International Labor Organization) and is working with them on a plan to help end slave labor around the world. “I come from a very poor state in Brazil where the labor relationships were always very wrong,” says Moura. “Brazil was the last country in the world to abolish slavery, so slavery is part of our history, of our soul,” he continues. “I started to get involved with that here as an activist when I started to realize how absurd things were. I started to support politicians who have human rights as a first action. Last year, the ILO people contacted me, which made me really proud. I am willing to do anything they want me to do because this is something that resonates a lot with me.”

These political ideals filter into Moura’s work. Tomorrow, Netflix will release their newest show Narcos, with Moura starring as the infamous Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar and Pedro Pascal and Boyd Holbrook playing the American DEA Agents sent to track him down. While in other hands, Escobar could be purely an awards-bait villain, Moura’s portrayal of him is much more thoughtful, and you begin to understand how Escobar was a populist working class hero while simultaneously devastating Colombia. Next up, the actor will direct his first film about the Brazilian dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s.

EMMA BROWN: I wanted to talk about how you got involved in Narcos. Obviously you already knew José Padilha, the show’s director.

WAGNER MOURA: Yeah. José and I, we are very good friends and we have worked together a lot. I did his first film, Elite Squad. Have you seen that one?

BROWN: Yes.

MOURA: Have you seen the sequel?

BROWN: Not yet.

MOURA: I really like the second one. The first one is about relationship of the police with drug dealers and how the police operates, but in the second one we go beyond that. It’s a film about not only the corrupt relationship of the police with the militia, drug dealers, but more than that the relationship with the politicians and the way politicians in Brazil use the police force in order to maintain the power they have here. I am really proud of that film. It’s action—kind of a boys, popcorn, cop film—but at the same time it’s very political.

BROWN: Did you ever have any politicians or policemen in Brazil criticize you for it?

MOURA: Oh yeah. José was sued by a lot of policemen here, especially after the first film. But no one won. Some police used to come up to us and say, “I like the film, because the film showed why we are the way we are, why we are corrupt, why we are violent.” The Brazilian police earn very, very bad salaries. They are badly paid, badly trained. They expose their lives every day fighting a war that doesn’t make sense. Killing drug dealers doesn’t help; it only creates more violence. When we talk about Narcos, we can also talk about that. I have a very personal opinion about the drug war. I think drugs should be legalized. If you see what’s going on, especially in countries that produce or are a way to send drugs to other countries—Brazil is a country where cocaine just passes through and goes to Europe; we don’t produce the cocaine—Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, that’s where the real violence is. There are many more people who died in this war than people that die from drug abuse. Drugs should be treated as a health problem.

BROWN: In America they have all these anti-drug PSAs that focus on, “Drugs are bad because you’ll become an addict and ruin your life” or “you’ll overdose and die.” I don’t understand why they never focus on, “You shouldn’t do drugs because children were kidnapped and enslaved on their way from El Salvador to the U.S. and died making these drugs for you.”

MOURA: Exactly. All the wars against drugs in poor South American countries, they imitate the North American approach to drugs. We know that the United States are involved in basically everything that has happened in South America in the past 50 years, especially after the Cuban revolution. They supported the right wing’s dictatorship in Chile, Argentina, Brazil…

BROWN: Nicaragua.

MOURA: With Colombia, they didn’t have dictatorship, but 80 percent of the cocaine that was consumed in the West came from Colombia, so the Americans were very involved in everything that happened in Colombia until today. That is the story we are telling [in Narcos]. José invited me to do [Narcos] because we did Elite Squad. He said, “I am going to do this thing for Netflix,” that was two years ago I guess, “I want you to play Pablo Escobar.” In the beginning, I thought we were going to do it in English. I thought, “Okay, I can speak English in an accent, no problem.” Then they decided—and I think it’s great—to do it in both English and Spanish. I freaked out because I didn’t speak Spanish at all. So I had to go to Colombia and learn how to speak Spanish. I was in a class with Japanese people, people from Germany, teenagers from China and Korea. It was a great experience, actually. It was like going back to school at almost 40.

BROWN: Who was the best person in class?

MOURA: I was a pretty good student. I did my homework.

BROWN: Did anyone know who you were?

MOURA: No, they did not, but then they ended up discovering. I didn’t want to get there and say I was going to play Pablo Escobar because I was in Colombia and I was a very skinny Brazilian guy who didn’t even speak their language, so I was kind of embarrassed to say what I was going to do there. I told them I was a student that wanted to learn Spanish. They ended up discovering what I was doing there and actually they were really cool and helpful. Colombia became a very important country to me. In Brazil we are very, very, isolated culturally—it’s a big country that speaks Portuguese surrounded by a lot of Spanish speakers, and so we didn’t have any relationship with people from Argentina or Chile. For me the greatest thing honestly about doing Narcos was feeling that I was part of something bigger than just being Brazilian—working with Mexicans, Chileans. Being in Colombia and feeling that the story I was telling resonated with me. I never felt like a foreigner there. I never felt I was telling something that I didn’t have a connection to.

BROWN: At the beginning of the show, Pablo Escobar is sort of a Robin Hood figure—you see how he is violent and creates violence, but the working class people of Colombia love him.

MOURA: He’s a very contradictory character. When I went to Colombia for the first time—even before signing with Netflix, I flew myself to Colombia. I went to this place called Pablo Escobar, which is a neighborhood that Pablo built for poor people. He gave houses to 2,000 people who lived in the town but didn’t have houses. The first thing you see when you arrive there is a big wall with Pablo’s face and Jesus Christ’s face, one beside the other. If you talk to people there, people are very lovely. Of course I didn’t tell them I was going to play Pablo; I told them I was an exchange student and I was trying to understand Colombia. They invited me in their houses, they offered me coffee, and they talked about how Pablo was good to them and you could see in a lot of houses a picture of Pablo in the living room. I can understand that, because it’s a matter of perspective. If I’m a poor guy and I don’t have anything and someone gives me my house, I don’t know if I am going to think this guy is bad. But at the same time in Bogotá, in Medellín, and in a lot of places in Colombia, everyone knows someone that was killed by Pablo Escobar or the bombs that he put in Bogotá. Colombia is very aware; they know who Pablo was, they know how bad he was, they know what he did to the country, but at the same time they acknowledge that there is a Colombia before and a Colombia after Pablo. You cannot just ignore it.

BROWN: Do you ever think about what would have happened if Pablo had become President of Colombia?

MOURA: He wanted to be a President. This is something that I love about Pablo, if Pablo had been working under shadows like most of the drug dealers do, he would be there now. The thing about Pablo is that he wasn’t happy with what he had—just being the sixth richest man in the world. He wanted to be loved, he wanted to be accepted, he wanted to be President of Colombia, he wanted his kids to go to the same school as the Colombian elite. But he wouldn’t be accepted by the elite. This left-wing kind of speech, the Robin Hood thing that Pablo had, of course he was a criminal and a mean person, but it wasn’t a false. He wasn’t false. I don’t know what kind of President he would be, maybe a very bad one, but I am sure he would do things for poor people—popular things that wouldn’t solve their lives but would help them. Maybe he wouldn’t be able to create jobs, but he would give them soccer fields, or houses, or free food once a week. But he would never be allowed to get there. He was elected as congressman—he got to the Congress—but the elite would not allow Pablo to get any higher. He was expelled from the Congress, and that’s when his war against the state began.

SEASON ONE OF NARCOS COMES OUT TOMORROW, AUGUST 28, VIA NETFLIX.