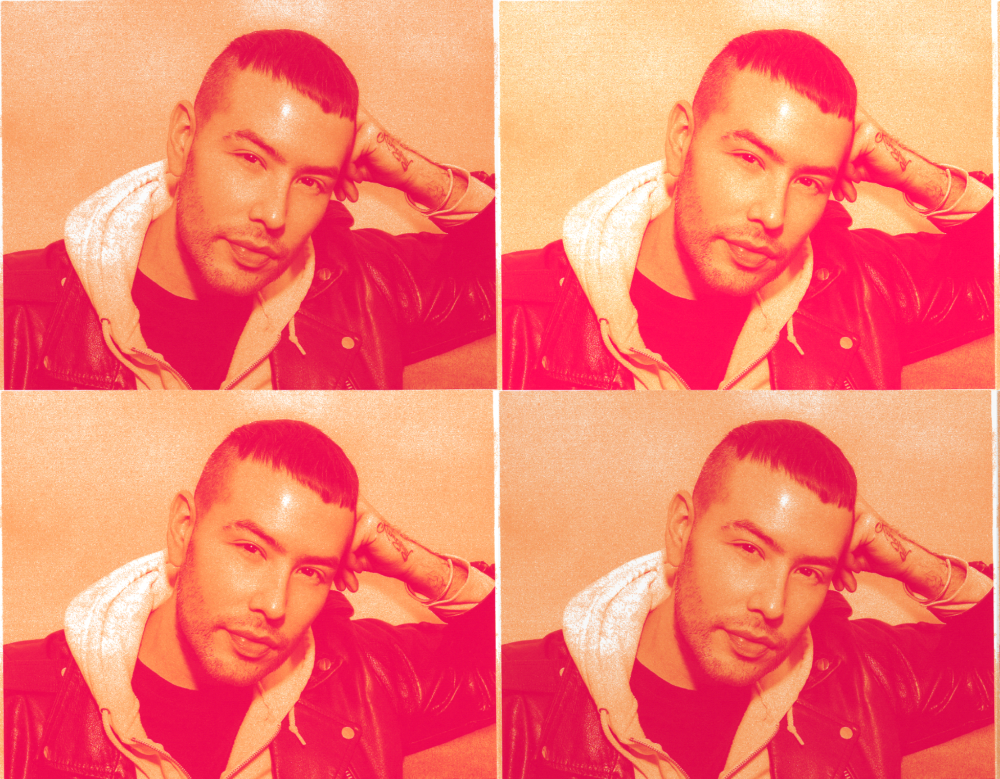

Tommy Pico’s Poetry Fuses Sex, Climate Collapse, and R&B

Photo by Niqui Carter. Art by Mark Burger.

Tommy Pico’s Feed is a madly defiant, dreamy poem. Part soundtrack featuring Beyoncé, Tears for Fears, and Aaliyah, part letter to the reader, part ode to springtime and complicated romantic love, Pico pulls us in with his irresistibly vulnerable and kaleidoscopic language. Whether smoking joints on a New York City fire escape musing about the probability of alien life, recalling the history of his ancestors, the Kumeyaay, an indigenous tribe who roamed the San Diego County area with the seasons, or waxing lustily on John Krasinski’s older brothers, Pico is on point. His sharp observations about searching for connection, American violence and cultural erasure of his people, as well as lovers, are both tender and forceful, demanding we pay attention. Pico’s book is full of knotty family history, ‘90s R&B, politics, sex, the impending climate collapse, and destruction of our planet. But through it all runs a stubborn ribbon of hope. With his poetry, Pico proclaims that he is here, still surviving, thriving, and exploring frontiers—however difficult or dark they may be. Interview sat down with the poet and spoke about feeling stuck, extraterrestrial life, American violence, romantic codependence, and catastrophe.

———

ROYAL YOUNG: The first few lines of your book are you having a conversation about writer’s block with someone. What happens when we feel blocked in our lives?

TOMMY PICO: There are many ways of being stuck. Some of them are being intimidated, or self-conscious, being under too much pressure or under the influence of some strong emotion. It happens all the time. There’s something very early on that speaks to being stuck, which is, we were afraid of having the conversation, because we already knew the answer. That happens a lot as romantic relationships are deteriorating. You don’t want to touch the house of cards, because you don’t want it to fall over, but it’s already in the process of falling. I wanted to capture a moment in a person’s life, a moment of them being a person who feels blocked and goes to a place of being more open and letting things flow.

YOUNG: Does this help in claiming your own power?

PICO: Yeah. There’s also this aspect of it that there is no arrival. It’s constant work. Because once you get unblocked from one thing, there’s another thing there to take its place. There’s no moment where everything is perfect and great. I mean, one of the most shitty things about going to the gym is that you have to keep going. You don’t go to the point where you don’t have to go anymore. That’s not the point of the gym, or writing, or life, or love.

YOUNG: We definitely live in a world where we are trained to believe in these cathartic moments, but no one ever talks about what happens after them.

PICO: Yeah, human beings are storytellers. And there’s got to be an end to the story.

YOUNG: Your friend in the book suggests aliens visited us millions of years ago, thought “This rock is trash,” and went on their way. Let’s talk about extraterrestrial life.

PICO: For me, it was a little bit of a metaphor for dating. Like, this person is going on all these dates with all these exoplanets. They’re searching for alien civilization and by the end, he realizes maybe he’s not ready for romantic love. Maybe civilization is actually super rare, maybe life is super rare. What if we’re the only outpost of life in the universe? Would that make you appreciate life more, or become more nihilistic?

YOUNG: I’d love to talk about you being ancestrally from the desert. You have a line, “drought made me restless.”

PICO: I’m Kumeyaay, so my nation is from the desert, going back before recorded history. There is something that, I don’t know if it’s genetic or spiritual, or what it is, but I feel my body was made for a desert. My body was also made to roam. Kumeyaay people constantly migrated around what is now San Diego County with the seasons. San Diego is very dry. It wasn’t meant for sedentary cities. If you’re a human being in that climate, you’re constantly searching for water. That’s another type of journey. I wanted to create other instances in the book of a journey that doesn’t have an end, that is constant.

YOUNG: You talk about not having a food history.

PICO: That’s a big part of imperialism, colonization and indigenous genocide both of lives and cultural genocide. Another way to subjugate a people is to estrange them from their ways of gathering and preparing food and making them dependent on the occupying force for that nourishment.

So, I didn’t have any food stories, these generational recipes. One of the projects for the book was making myself cook with people in their kitchens and tell me stories of the dish they were preparing. It was through them that I started to also gain food stories. That was really important for my spiritual life. It felt better in my spirit that I had shared these stories with people.

YOUNG: When you talk about nourishment, that is two-fold. There’s the food itself and then the stories and cultural histories attached to it, which come with its own kind of soul nourishment.

PICO: Yes. The idea of that being stolen from a people is so cruel, on top of literally trying to eradicate them. The fact that we survived is a miracle to me. This is me making good on that miracle.

YOUNG: Does death add to our search for connection?

PICO: Death has loomed over my entire life. My first memory is at a funeral. Non-native people don’t really understand how we just deal with death on the daily. It’s so constant. I’m not talking about the prospect of death and old age. People die on my reservation in their 40s. That’s the average. So, as a person who is 35, I feel like I’m making all this stuff and working as hard as I am because in my mind, I’ve got five years left. I know that’s not practical, but that’s the lesson I learned growing up. That’s my formative experience. I don’t feel like I have time to waste.

YOUNG: How does American violence affect us?

PICO: Well, it’s sewn into the fabric of the United States in ways that I think people at large are unwilling to face. Now, the seams of that are coming apart. Everyone sees it now. The idea of America as not being a violent place is really at the root of that. There’s some kind of American exceptionalism, that America is great. No, actually the real history is that this place is built on indigenous genocide and black slavery. The Earth is soaked in our blood.

We have a legitimized wave of white supremacy in the current political sphere. And people are like, “I don’t know my country anymore.” But for me, I’ve always known those people. I went to school with those racist, Nazi, KKK people. I’ve known them my whole life. This isn’t a surprise to me.

YOUNG: Your therapist, Dr. John, asks, “Does it all have to be codependence or isolation?”

PICO: [Laughs.] That is the 69 million-dollar question. I would like to imagine that exists. I really would. I didn’t have the healthiest of models growing up. I felt like I was around two people who were committed to making each other miserable, while in love. In tackling the question of if there’s a fertile ground between codependence and isolation, I’d rather just surrender to the isolation. I just have catastrophic imagination when it comes to romantic relationships.

YOUNG: Is isolation all that bad? Can’t we still find poetry within ourselves?

PICO: That’s what I’m proposing. That there are so many different types of connection. So many people are walking around with pain they don’t know how to talk about or how to place. Finding moments of connection can become moments of salvation, and moments of creative vigor.