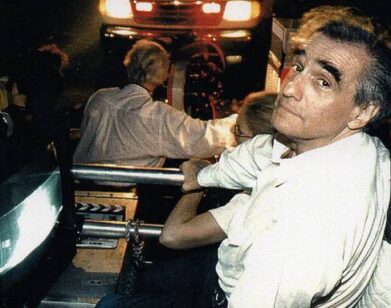

Tom McCarthy Is No Longer a Well-Kept Secret

PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

There is a vicious rumor circulating that Tom McCarthy is the writer of our generation. It’s a particularly vicious one because 42-year-old McCarthy wasn’t vetted by the literary establishment, edited, groomed, and promoted as contemporary literature’s new voice of radical narrative, before many got the chance to read him and make that decision for themselves. McCarthy’s ground-breaking novel Remainder, about a young man awarded 8.5 million pounds for an unnamed accident who spends his money re-staging and re-enacting quotidian (and increasing less quotidian) scenes of life in order feel “authentic,” was first published by Alma, a small art press, before the larger houses discovered it by word of mouth.

The British novelist is a rare example of a recent successful fiction writer to spring out of the contemporary art world, a relationship McCarthy continues to stoke as the founding member of the International Necronautical Society, an anarchic manifesto-empowered action group that promotes death, failure, and inauthenticity among its chief attributes.

His sweeping novel C, an adventure tale that also plots of the history of modern communications, arrived in 2010, and now, just last month, his novel Men in Space, first published in the U.K. in 2007, managed to get through customs. Men in Space, like Remainder, concerns itself with alienation, failure, the inauthentic gesture, and a meaningless search for meaning, but it is also astounding funny, goofy, and at times, dead serious. The novel takes place in Prague just after Czechoslovokia’s independence from its Communist regime thanks to the Velvet Revolution, and the plot follows the forgery of a Byzantine icon painting through squalid young bohemian art circles, trailing police agents, bygone cafes, a Czech mafia ring, and even through the rest of a ramshackle Eastern Europe reconstituting itself with a taste for capitalism (and art!). The writer’s gorgeous prose creates passing scenery of great beauty on the car ride to despair. McCarthy actually spent his early twenties in Prague, as a hopeful writer and nude figure-drawing model (not unlike the British expat art writer Nick in the book). McCarthy is clothed for late-winter weather as I meet him for oysters in late February to discuss writing, art, and the fetishes of great literature.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Let’s start with a clarification. Men in Space is your latest novel, but it’s really your first. Or is it your second?

TOM MCCARTHY: Men in Space is the first novel I wrote, and I finished it in ’99.

BOLLEN: It is set in Prague the same time you were living there, but you wrote it later when you were in London.

MCCARTHY: Yeah. I was in Prague from ’91 to ’93. I moved back to London in ’96. First I was in Prague and then I went to Berlin and then Amsterdam. I finished Men in Space in 1999, right before the new year. The original version has a weird history. Someone at 4th Estate [publishing house] was going to do it. The editor just said, “Yep, yup, we’ll do it,” and I thought, “Wow, this is easy.” A few weeks later, he said, “No, I’ve been overruled, I can’t do it.” This happened at three or four publishers. No one would do it. So I just put it in a drawer. I wrote Remainder, and no one would do that either. Finally a little art press did Remainder and then Marty Asher at Vintage did it. Then it kind of got published all over. Of course, when you have one thing that’s taken off, people want to do the other things. So in 2007 I revisited Men in Space—I liked it but it was too big and too bulky.” It was a first novel and I have First Novel Syndrome. So I rewrote it and I’m really glad that it worked out that way. It’s a lot leaner and a lot sharper than it was.

BOLLEN: Did it have all the discordant narrative voices from different perspectives—artist, police officer, thug—that shape the chapters from the outset? Was it structured the same way?

MCCARTHY: Oh, yeah, it was structured exactly the same. It was just fatty. There were ten-page interior monologues of Nick while he’s modeling for the art class—stuff that you just don’t really need. I had just read Infinite Jest, which I thought was brilliant, and still do, but I think there was too much of that kind of [David Foster] Wallace talk. So Men in Space came out in the U.K. in 2008. And Marty decided he wanted to publish it but after the one I was working on. That’s why it’s coming out now.

BOLLEN: I admire your determination. It’s one thing to have the confidence of an immediate first-novel success story. But I much prefer the story of a writer who keeps writing in the face of rejection, and hiding those books in drawers.

MCCARTHY: I always wanted to be a writer. Maybe I was just arrogant. But I thought what I was writing was okay—and lots of editors did too. They just couldn’t get it past their marketing departments, which are generally more conservative. I finished Remainder in 2001, weeks before September 11, and I don’t think I started C until 2004. So there was a three-year hiatus. Instead I did art projects—I moved into the art world. Some of the stuff I was doing in the art world was literary, as far as I was concerned. I had this project at the Institute of Contemporary Arts London where we were cutting up text, very William Burroughs, and recompiling it and reading it out over the radio. It was actually through my involvement with the art world that Remainder got published. An art press did it, initially. They distributed it through art galleries and museums, but not mainstream bookstores. I detoured through the art world in order to get published.

BOLLEN: I feel like the connection between literature and the visual arts today is stagnant. There is much more of a relationship between visual artists and poets. You’re an exception.

MCCARTHY: It’s true. There isn’t as much crossover as there should be. But I think also, generally, here in America it’s different. In the U.K., if you want to talk about Burroughs, as I’ve mentioned, or Beckett, or Kafka, most people in publishing just haven’t read that stuff. They’re not interested. Whereas people in that art world…

BOLLEN: Why is that?

MCCARTHY: Publishing has gone very middlebrow. I know people keep complaining that it has here too, but in the U.K. it’s much worse. It’s turned its back on this legacy of modernism and gone into a humanist mode. I guess when people go through art school they are exposed to the history of the avant-garde, and there’s a general understanding that what you’re doing as an artist is to a large extent, not just regurgitating that history, but engaging with it. There’s this denial of that in the mainstream publishing world.

BOLLEN: I feel like I’m in a “Twilight Zone” episode with you complimenting America on its experimental, anti-consumerist tastes.

MCCARTHY: I think America is more receptive. Here, people like Ben Marcus or Shelley Jackson get published by the same house as I do. They’re within the Random House group. In the U.K., nobody will touch them, not even an independent. They’re just too left field, too weird.

BOLLEN: Getting back to Men in Space, when you were living in Prague, did you take on jobs like the character Nick?

MCCARTHY: For the first year I was in Prague, I had a grant from the U.K. government. They had this thing for a few years called the Government Enterprise Allowance Scheme, and it was a ruse to get the unemployment figures down. Instead of being unemployed, you could register as a small business. You had to come up with a business idea. For a couple of years, they decided to let artists and writers do it as there was a loophole. If you said, “I am a small business that markets literature,” they would let you go on it and would give you this stipend. It was like 100 bucks a week. It wasn’t very much. I got it and went to Prague and lived like a king on that amount of money. Then it ran out, and I was doing Nick stuff. I was modeling at the art school every morning.

BOLLEN: Do you keep any of the drawings young Prague students did of you in the nude? There might be a whole series of obscene portraits of you out in the world right now.

MCCARTHY: Yeah, I don’t know if any of those kids made it big. But there were a couple of really talented ones. It was very classical there, after years of very traditional communist pedagogy. They spend a whole year just copying the statues, then go onto live models. I modeled every day for about four hours or so.

BOLLEN: And you were also writing.

MCCARTHY: It was like an apprenticeship. I was reading a lot. I would copy out whole passages, or sit down and try to translate Rilke’s Duino Elegies. And I did write something, a novella, although it doesn’t stand up now as something—I was 22.

BOLLEN: Were some of your early notes incorporated into Men in Space?

MCCARTHY: Yeah, for sure. In fact the novella I was writing was about an art forger. It was set in London, but it had the same themes. It was based on the Elmyr de Hory art forgery scandal, which Orson Welles made that movie about.

BOLLEN: F For Fake! I love that movie. It’s one of the best documentaries, and pseudo-documentaries, of all time.

MCCARTHY: I’ve always been obsessed with art forgery and forgery in general. Even Remainder is all about doubling and repetition. So I guess a lot of that did find its way into Men in Space.

BOLLEN: I hate when interviewers ask writers if they worked from an outline, but I do want to ask that because the structure of the novel is quite convoluted, even if the plot is straightforward. Did you plot it or figure it out as you went along?

MCCARTHY: I figured it out as I went along. When I started writing, I didn’t even have the plot in place. It was just going to be a Prague novel. And then I realized I needed a plot. The first part was really difficult. It took about two years. The second half went really quickly, like six months. I always find it difficult to get that critical momentum, what they call Mach 2 with airplanes, what you need to take off.

BOLLEN: Men in Space deals with some themes familiar to Remainder, but the writing style and voice are entirely different. It’s impressive that you can switch tones and perspectives so smoothly in your fiction.

MCCARTHY: I think there’s a set of concerns that I reiterate or modulate. It’s about doubling and this idea of failed transcendence. In Remainder he’s trying to get the blue goop to go up and materialize [in one scene, the narrator tries to recreate an episode at a mechanic’s shop where window-washing fluid shoots up and disappears almost by miracle], it just gushes down on him and everything just falls down—matter gets in the way. And it’s similar in Men in Space, the failed transcendence of the icon. It should be going up to plenitude, God, but instead there is this ellipse, this absence. Then there’s the political level. Eastern Europe is expecting this wonderful generation and what they get is Starbucks, [laughs]. Basically, neoliberal capitalism. There’s all there is in the end—the police agent just sitting in this junkyard, where everything seems to have fallen back. And of course the radio really prefigures Serge [the main character of C] and his whole radio and the deafness obsession. Each book suggests concerns for the next ones.

BOLLEN: It’s pretty incredible to have novelist who is part of a group that actually champions a manifesto. Are you still part of INS [International Necronautical Society]?

MCCARTHY: Yeah, that’s going strong. In fact, the collected manifestos and denunciations and proclamations are about to come out in English with Sternberg Press, a really good art press. The INS is for me a literary project, but it’s played out through the art world. There’s nowhere else it could be played out. In around 2000, I was really interested in the art manifesto as a literary form—bombastic, arrogant, funny.

BOLLEN: The Futurists perfected that genre with their manifesto.

MCCARTHY: The Futurist one is the best ever-it’s brilliant. Of course, they’re fascists, but they’re also incredibly subversive. They’re like the first media theorists. What they did pretty much opened up Roland Barthes and Derrida. It opened up great possibilities for the left, even if it was coming from the right. The Futurists, the Surrealists, the form of the manifesto and how it belongs to this early 20th-century moment of vertiginous revolutionary upheaval. I was thinking a lot about death, and reading Blanchot and other thinkers. For Blanchot, the space of literature is a deadly space, being towards death. I wrote this manifesto—I wouldn’t call it a parody, though it was obviously tongue-in-cheek—trying to use that tone of Marinetti and the Futurists but I made it so it could be about death rather than about technology. Then I just floated it around. As I said, I was quite involved in the art world. I just Xeroxed it, handed it out to about a hundred people, and a couple galleries were saying “This is conceptual art, have an exhibition.” So I appointed committees and subcommittees. I’m really into Kafka, and Burroughs, and Pynchon, and the idea of hidden networks. So I put philosophers and artists and got them to compile reports. Then we had these quite big events in galleries where we summoned other artists, filmmakers, philosophers, whatever, and we’d interrogate them aggressively.

We worked with this woman, Laura Hopkins, who’s now working with the Wooster Group. She’s a set designer. We made her our environmental engineer and she has this brilliant knack of looking at a photo of the Stalin Show Trials or the McCarthy Un-American Activities Hearings and then reproducing that space. So we turn an art gallery or a museum into a really aggressive interrogation room and we interrogated people, I mean quite seriously. It wasn’t a joke. Then we would publish reports. So that kind of took on a life of its own.

BOLLEN: Do you consider INS an entirely separate project?

MCCARTHY: It’s completely joined. Like I had the idea for C, while I was doing this INS project at the Institute of Contemporary Arts when we had a radio transmission room. I was doing all this research about the emergence of radio and its relation to death. Radio totally has to do with death, by the way. People thought they were hearing their dead relatives in the ether. And with deafness, the telephone, and Alexander Bell and his family. I mean, the father in C is totally Alexander Bell’s father. Anyhow, while I was researching the INS project, I had an idea to do C, and they go hand in hand.

BOLLEN: In America, INS also stands for our Immigration and Naturalization Service.

MCCARTHY: I actually got stopped at customs once and they opened my bag and there’s this INS card!

BOLLEN: Was the obsession displayed in Remainder for reenactments ever a personal obsession of your own?

MCCARTHY: With Remainder, it’s autobiographical inasmuch as I had that “crack in the wall” moment. I was at a party, and saw the crack, and had the moment of déjà vu. And I thought initially, “I can make an art project.” But what’s so interesting about that, you make a room that you remembered? So what? It’s only interesting if you can expand the zone all the way out to the point of ultra-violence, until you are dying in it. At that point it has to be a novel. Or a mass murder spree.

BOLLEN: I hope this doesn’t sound strange, but Remainder‘s obsessive reenactments, which involve even the smallest quotidian movements, reminded me almost of how fetishists treat sex. Now you do this to me, now I do that to you, now you put your foot here…there’s this over-rehearsed exercise to the act of sex.

MCCARTHY: Oh, yeah. There’s a huge sexual element. Someone asked, “Why is there no sex in the book?” My answer is, “It’s all sex.” The whole thing is sex. I was looking at Sade when I was writing it. I read it when I was about 20, but I hadn’t reread it, and 120 Days of Sodom is all about reenactment. There are four libertines, four perverts, who are incredibly wealthy and they kidnap all these teenage kids. 11-, 12-, 14-year-old kids. And they take four high-class prostitutes with them to this castle, this room, and he meticulously describes the layout. It’s a room with four alcoves. And one libertine sits in each corner. The kids go on the floor, and a prostitute stands in the middle and starts telling stories. One time, she’s fucking these three guys, one time, blah blah blah. The rules are, at any point any of the four libertines can go, “stop, that bit is good, let’s do it.” They use the children as extras, and they reenact it. They also modulate it. They say, “It would be even better if, instead of four of us, there would be six,” almost like an algorithmic set of variations. So there’s this space within narrative, where you can move from being a passive listener to an active doer, or a re-enactive doer. And this is a move into violence. I think that logic is central to Remainder. It’s a sadomasochistic sex game all the way through.

BOLLEN: I suppose some might call the main character of Remainder autistic in his obsession. It’s like when you’re a kid and you must walk back exactly the same way you came, stepping on the very same spots in the ground or else the whole world will explode.

MCCARTHY: He kind of has to have OCD but not entirely. He’s stuck with impuissance. I think everyone in all of the books I’ve written is stuck with impuissance and their challenge it that they’re trying to work out, like a laboratory rat in a maze. They’re trying to work out the labyrinth like Theseus or Oedipus working out the patterns they’re in. Or in the case of Remainder, he’s not even working it out. He’s just triggering and retriggering it.

BOLLEN: What I love about him is that in all of his monumental act of creating, he’s the passive entity.

MCCARTHY: He actively creates a space in which he can be utterly passive. Even to the extent that he’s not doing actions, they’re being done. He’s being killed, guns are being fired but he’s not firing them. Yeah, it’s passivity. It happens in Men in Space as well. There is a kind of story that going to play itself out and nothing anyone does is going to change it. It’s going to happen. Again, it’s the whole Oedipus thing. It happens in Beckett as well. They say what’s happening, something is running its course-an endgame. You can’t change it, you just become passive in front of it. This mode in literature goes against the more middle-brown mode, which is about shaping your destiny, changing it. It’s almost a kind of self-help stuff. You can change your life, and I want to say, no you can’t. Even if we live in a godless universe, there are paths set, there are trajectories, like bumper cars just pulling those trajectories, colliding.

BOLLEN: You’re working on a new novel right now, correct?

MCCARTHY: It’s called Satin Island…don’t hold your breath. It’s going slowly. I’m about 12,000 words in. I’ve done about forty thousand words but only 12 of them are any good. It’s just a lot of burn prose. It’s always that way at the beginning. I just generate. It’s like all of these dot-com’s. They have all this burn money.

BOLLEN: So you’re still in development stages. I find that my favorite part is developing the characters. It’s when I need to apply them that it’s challenging.

MCCARTHY: I’m reading a lot, I’m reading a huge amount. I’ve read like The Magic Mountain, and Between the Acts, and later Renaissance stuff.

BOLLEN: Some writers find it very hard to read while writing. They are worried it will leak into their work.

MCCARTHY: I find it exactly the opposite. Because this is how I understand literature—as a kind of remix or echo chamber. What’s going on in a literary work are other literary things disinterred, cannibalized, and recombined. The narrator is an anthropologist. I’ve been reading lots of Levi Strauss and about anthropology. You read one thing and it leads you to another. I’ve been reading lots of Mckenzie Wark and Manuel Castells—kind of network thinking, systems thinking, and then hacker thinking. Not computer hacking but information hacking. For Mckenzie Wark, all art is a form of hacking, it’s a kind of breeching open of a closed system. I find that really interesting.

BOLLEN: In Remainder and Men in Space, the endings are similar. They take place in the air, up, and the main characters exist in a temporary holding pattern where their lives are presumably about to end.

MCCARTHY: They become absolutely passive and stuck in this kind of suspension. Again, coming back to David Foster Wallace, I just love the ending of Infinite Jest. It’s similar. This guy has his head frozen to a window-pane, and he can see the disaster that’s about to happen—the wheelchair assassins are coming, it’s all going to go wrong. Everyone is about to die and he’s just physically stuck to the window. I like that. That sense of looking down unable to…

BOLLEN: …intercede.

MCCARTHY: Which is like the cosmonaut stuck in space or maybe like the writer too.

MEN IN SPACE IS OUT NOW.