q&a

The Sensual, Unsettling Art of Jared Buckhiester

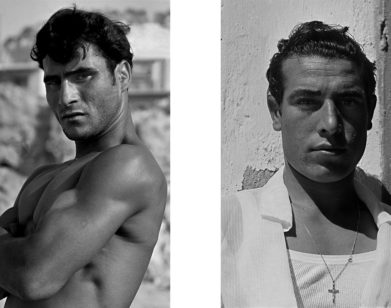

Last April, Manhattan-based artist Jared Buckhiester invited me to Fishers Island, located on the eastern end of Long Island Sound, for the installation of his latest exhibition of work at Lighthouse Works gallery. The show wouldn’t open until Memorial Day, and Buckhiester wanted my thoughts on art titles. We huddled among his works in the early spring chill of the gallery, guiding our conversation around male desire and the way it frames Buckhiester’s artistic practice. One stormy night, we watched Robert Eggers’s The Lighthouse in the spooky old house of the gallery’s residency program. The next day, we hiked out to the rocky beach near the supposedly haunted Race Rock Lighthouse. In other words, we were immersed in the ghostly maritime atmosphere of the exhibition, which is now titled “too fair-spoken man”—a euphemism lifted from Billy Budd. Buckiester’s sexy and unsettling new art pieces—which range from charcoal drawings and color photographs to ceramic figurative vessels—tackle the trouble and attraction of masculine aggression and the capacity for its inverse, tenderness. Throughout his career, beginning with delicate, intricate drawings of male bodies in scenes of intimacy and brutality to voyeuristic close-up photographs of truck drivers in transit on the highway, Buckhiester’s subjects have continually wrestled with the allure of masculinity. We spoke about “mascing up”, father-son road rage, and the kind companionship of art objects.

———

ZACHARY PACE: How has your thinking about masculinity evolved over the course of your practice?

JARED BUCKHIESTER: In my earlier work, masculinity was a default subject because my practice was a sort of revisionist history, illustrating the feminine parts of myself. What I consider the first works I made as an artist in earnest were these drawings of sissies in the rural south, from 2005 to 2009. In my mid-twenties, I started to appreciate the parts of myself that I’d had to “masc” up in order to fit in—you know, putting on the affect of not being a fag, so you can still participate. And I was fortunate—or unfortunate—enough to shift into both worlds easily. My physicality could be masc’ed up enough to where I wasn’t bullied. But these early drawings were about glorifying the feminine aspects of myself—these effeminate characters in rural landscapes doing devious things, or in loving embraces with older masculine figures.

PACE: How did these ideas come into play when you started to make photographs? I’m particularly wondering about your photos of truck drivers. How did you stage these spontaneous portraits of them at the wheel of their vehicles?

BUCKHIESTER: I’m realizing now—and maybe this is a result of being in analysis—everything depends so much on the past feeling in the present moment. Even though I began photographing the present moment, the setup of the game of making photographs of truck drivers was a reenactment. My father drove the SUV, while I sat in the passenger-side back seat to take the photo. The impulse to do it happened when he was driving me to the airport. I climbed into the backseat because the window’s bigger. It was incidental, but also deeply subconsciously driven—a recreation of something I’d done for a long time—passing time on the highway, looking at these dads on thrones on the highway. There’s trouble in the re-creation of that game: my insecurity and guilt about doing something transgressive with my dad in the car, and also crossing someone’s boundaries—invading someone’s space—the truck drivers, in particular.

PACE: You often pair your ceramic urns with the trucker photos.

BUCKHIESTER: They’re portable urinals, loosely based on Mesoamerican forms. I was playing a narrative game with myself. When editing the photographs, my visceral feeling was guilt, like I’d really done something wrong, so I followed this narrative as a game to produce an object to pair with the photographs—the impulse to make a gift as an apology. I started making these ceramic urinals—an apology and a further transgression at once. The Mesoamerican reference is to the earth that we now inhabit—the history of that earth—the transhistorical logic to desire, masculine aggression and its arousal template . . . it’s not just a gay man’s problem. It’s a forever phenomenon.

PACE: What are your artistic influences for all the symbols of masculinity—the clothing and accessories, but also the aggression and tenderness—recurring throughout your work?

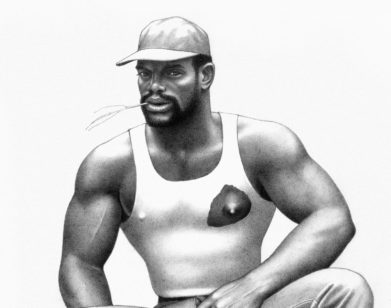

BUCKHIESTER: I’m thinking of Tom of Finland. What’s depicted in those drawings is aggression. It’s a joyful aggression. The community is formed around masculine aggression—or the performance of masculine aggression. But tenderness is being sought. All my lacy drawings of cowboys fucking in pastoral scenes or cowboys weeping in pastoral scenes are a direct response to Tom of Finland. So, it started as an extension of a lineage of erotic gay drawing and photography: Tom of Finland, Bruce of LA, George Dureau, Mapplethorpe . . . the symbols that show up in those spaces. Karlheinz Weinberger . . . the outfits are so seductive and erotic. It’s an erotic experience to draw a cowboy in a cap and chaps weeping, even if he’s not oversexualized. It’s a way of understanding desire to begin with. I grew up around hillbillies wearing boots and work clothes. It’s attached to eroticism in my memory. But in the work, I use them as graphic devices or obscuring devices. The hats are obscuring devices for the face. I use them for their symbolic potential, to point in more than one direction, but they’re still functioning as an obsessive impulse around desire.

PACE: How does all this come into play around the new work in your show on Fishers Island?

BUCKHIESTER: This work was all made from March 2020 to February 2021. The photographs were taken in 2015, but they were chosen and edited and printed this year. During that time, I was less alone than I had been, because I was living in Great Barrington [Massachusetts] with a friend—living with someone for the first time in ten years—and so I was more not-with-myself than before. I got the confirmation for the show about three months before I was meant to install it. And I had tons of work from the last four years that I could’ve shown. Because it was going to be on Fishers Island—which is, historically, this place of wealth and exclusivity—the truck-driver photographs seemed like a startling starting point to build the show around, and especially the one of the driver drinking soup that he’s holding with an injured hand. I wondered, How can I make this photograph feel okay on Fishers Island? Maybe that instinct came out of the desire to comfort such vulnerability with community because I got to feeling good about the selection for the show when surrounding this truck driver with companions. Until now, I’ve not really understood my work as having a communal impulse—but, in talking about it, I have to admit that’s what I’ve been up to all along.