TELL-ALL

“I’m a Woman, Darling”: The Life and Times of Warhol Superstar Holly Woodlawn

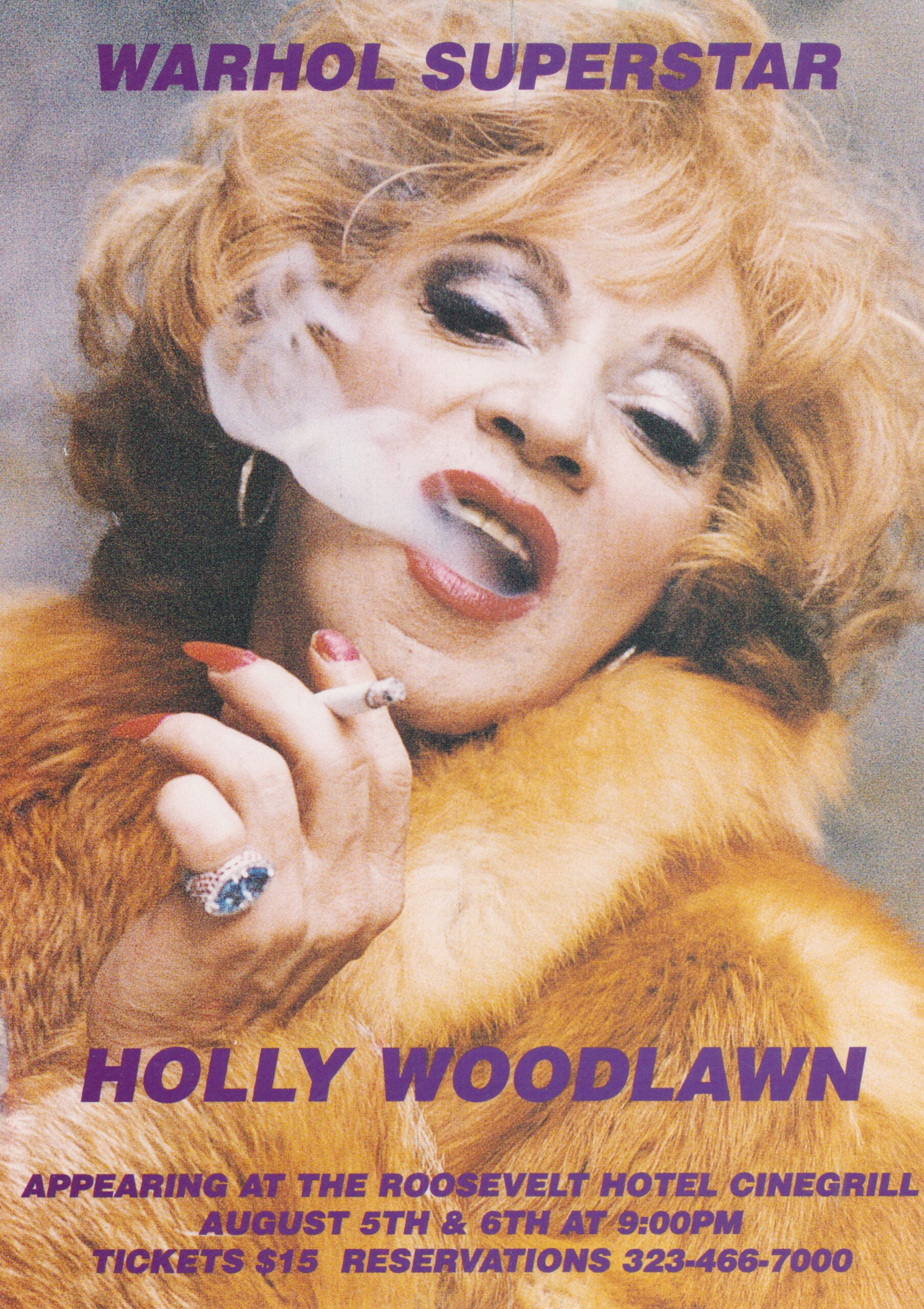

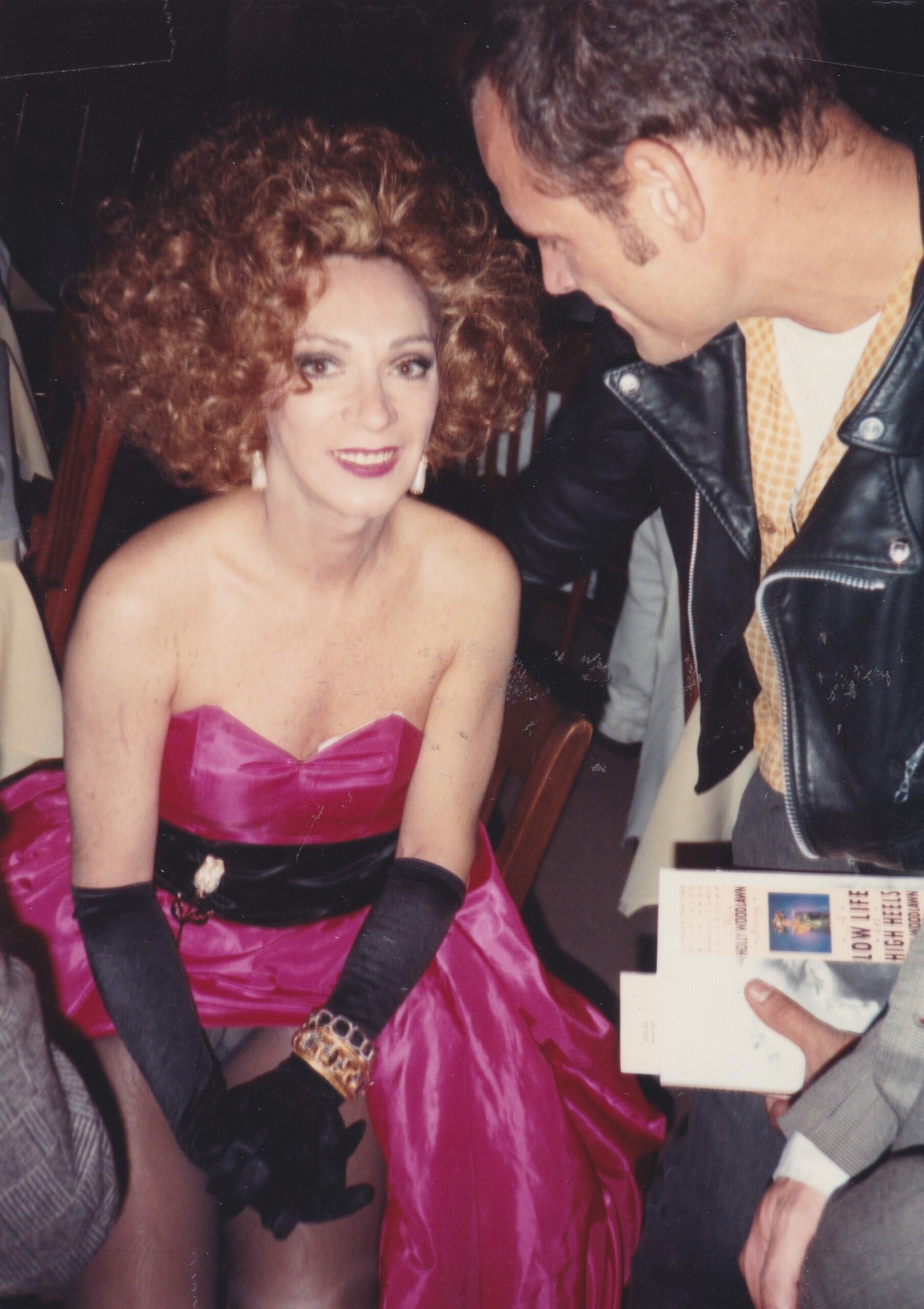

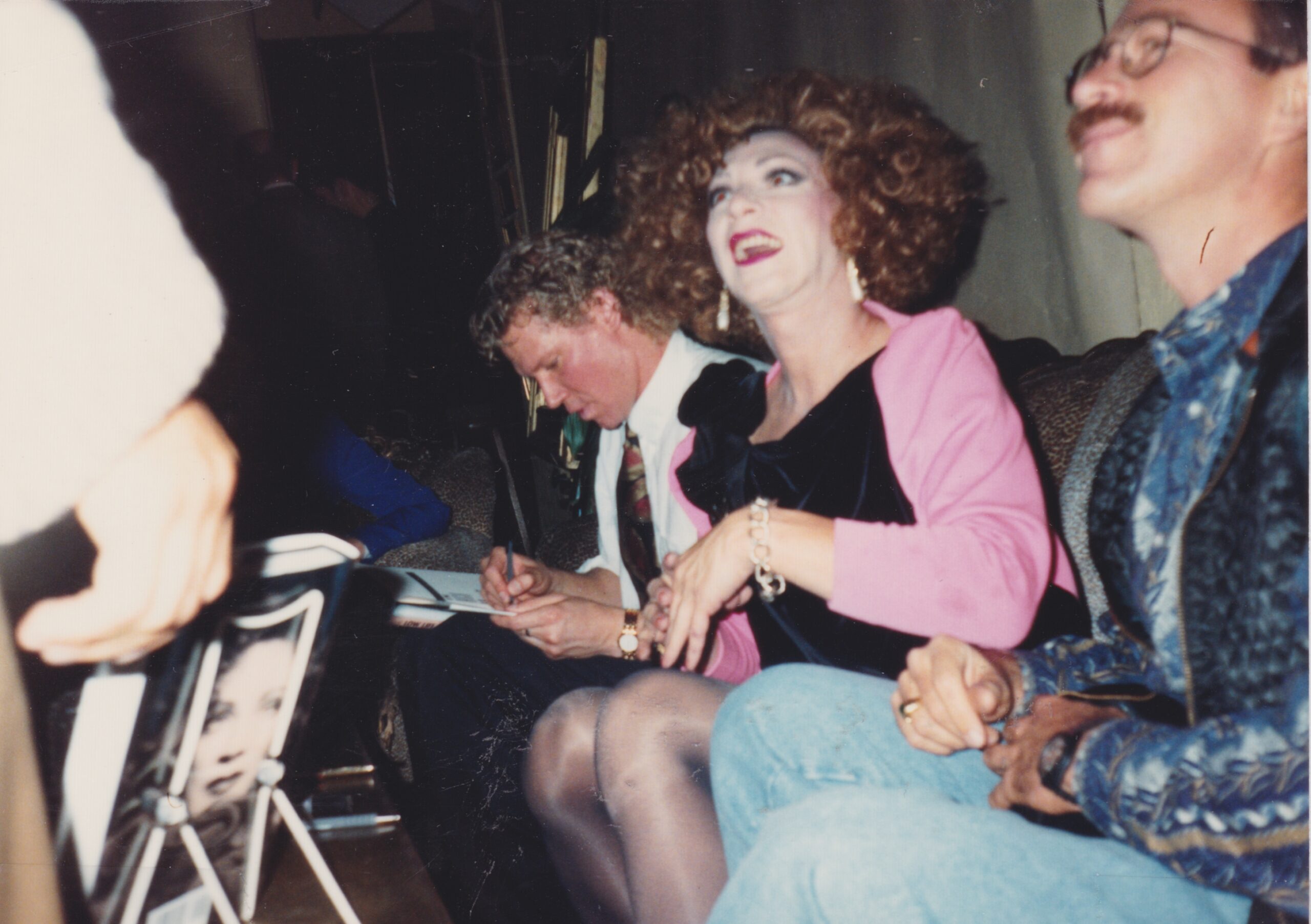

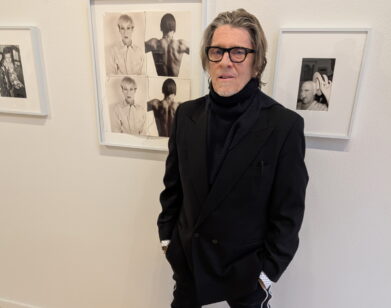

Holly Woodlawn was Andy Warhol’s spiciest superstar, the Factory’s own Anna Magnani. Following her volcanic breakthrough performance in the Warhol-produced, Paul Morrissey-directed Trash (1970), the Puerto Rico-born transgender trailblazer would be immortalized by Lou Reed in the lyrics to his 1972 hit “Walk on the Wild Side,” dressed by Halston, photographed by Richard Avedon and feted by Truman Capote as “the face of the seventies” (although rumor has it the writer may have said those exact words to Woodlawn’s peer, Candy Darling, too). By the time the naïve aspiring screenwriter Jeff Copeland encountered Woodlawn in Los Angeles in 1989, the diva’s fortunes had taken a downturn. The odd couple would collaborate on Woodlawn’s 1991 autobiography A Low Life in High Heels and now, almost a decade after Woodlawn’s death, Copeland reflects on their friendship with exasperated affection in his juicy new book Love You Madly, Holly Woodlawn: A Walk on the Wild Side with Andy Warhol’s Most Fabulous Superstar (published this month by Feral House). On the heels of Cynthia Carr’s acclaimed 2024 biography of Candy Darling, and the recent death of Paul Morrissey, we’re overdue for a reappraisal of Woodlawn’s life and career, too. So last month, over Zoom, I peppered Copeland with questions about his thorny but ultimately life-changing friendship with Woodlawn.

———

GRAHAM RUSSELL: So the book starts with you as a little boy in small town Missouri, obsessed with the glamour of old movies. You would eventually find your own Hollywood Glamazon, but with a twist.

JEFF COPELAND: Right. I started that story that way because I felt it was important to explain who I was as a person, where I came from, and why I would get mixed up with Holly Woodlawn in the first place. We had a lot of commonalities in that we had to escape where we were born to seek the freedom to be ourselves. She ran off from Florida to New York City. I ran from redneck Missouri to Hollywood, and it was such a hard struggle for me that, by the time Holly Woodlawn came into my life, I was just desperate for an opportunity. And she was the first person in Los Angeles to go to bat for me.

RUSSELL: I love how you paint such a vivid picture of what L.A. was like in the 1980s. You talk about the Tail O’ The Pup hot dog stand, Santa Monica Boulevard with the gay hustlers, Angelyne billboards, spotting the Lava Lady.

COPELAND: Well, Angelyne and the woman who would float down Melrose with that big horn—they were iconic of that era, and that no longer exists. Dennis Woodruff, the guy who ran around Hollywood in those crazy cars promoting himself as an actor, died recently. So all that’s going away. When Angelyne goes, I’m not sure what’s going to be left of the ’80s. I really wanted to take people on a trip back in time.

RUSSELL: One of your earliest jobs when you arrived in L.A. was a production assistant on Big Top Pee-wee, and you don’t really go into detail about it, but you must have some Pee-wee Herman or Susan Tyrrell stories.

COPELAND: Yes. Well, I started out working in the art department as a production assistant to the art director. And then once everything was designed, I transitioned over to work as Paul [Reubens]’s direct assistant for a few weeks toward the end of filming. And he was just wonderful. I mean, it was a great time. It was a circus movie, and it was so much fun. Susan Tyrrell, I didn’t work directly with her, but a friend of mine did. He would drive to Venice and pick her up, and she would have him stop off at the local market and pick up a six-pack of beer. And she would drink her beer as she was on her way to the sound stage. It was just a great experience. I loved working at Paramount. I worked at Paramount for three years as a production assistant, but I got stuck in that trench, and I really wanted to be a writer. Ironically, I worked on a gay TV show called Brothers, which was a landmark series for Showtime, and no one on that show was gay. We had a gay consultant, and I was very closeted at that time. Long story short is, I couldn’t get an opportunity. I was fetching coffee and Xeroxing scripts, and there came a point when Paul Reubens asked if I would come on board as his assistant. I actually turned him down because I wanted to work with Holly Woodlawn.

RUSSELL: Well, it paid off. It’s a total fluke that you were helping a friend who was organizing a party, and you spotted Holly Woodlawn there as a guest and became totally transfixed. You had no idea who she was, but you were intrigued by her and her androgyny. Looking back, what was it about her that you think fascinated you so much that night?

COPELAND: It was Dorian Hannaway’s birthday party, and there were a lot of TV folk there. I thought it would be a good networking opportunity, and I got transfixed with this androgynous being. I could not figure out who this person was. It was very weird, I was just riveted. My friend was standing next to me and he said, “That’s Holly Woodlawn. She’s an Andy Warhol superstar.” He was kind of dismissive, but I could not get over this character. I had no idea what an Andy Warhol superstar was. When I look back at it, it was almost like divine forces were causing me to focus on her. Because at that time, the writer’s strike was going on in Hollywood and production work had closed down. I was looking for someone to make a little independent movie with, and Holly Woodlawn just stayed on my brain. I couldn’t shake her. That movie, of course, was never made, but that was the impetus for the book. I looked her up. I didn’t have a phone book, so I called the operator and Holly Woodlawn was listed. I called her up, asked her out to dinner, and we hit it off.

RUSSELL: And that’s fascinating because, like you say, the film never happened. Instead, you wound up co-authoring her memoir, A Low Life in High Heels.

COPELAND: I think that was really fortuitous because, had I made a movie with Holly Woodlawn, I don’t think anybody would remember it. I mean, I was so naive and ignorant when I first got to Hollywood— I didn’t know what I was doing. All I knew was I just wanted an opportunity. And I did not want to write a book. I wasn’t a book writer. I wanted to be a screenwriter.

RUSSELL: It’s interesting to me that, when you first encountered and befriended Holly, you didn’t have a background in Warhol cinema or Warhol superstars.

COPELAND: Yeah, I didn’t know anything about it. I did run down to Video West because we didn’t have the internet then. You couldn’t just Google someone. They did not have Women in Revolt, but I watched Trash. I did what research I could, which was very little.

RUSSELL: In the years that have passed, you’ve now written two books about Holly. What do you think made her unique or exceptional as a Warhol superstar?

COPELAND: Now, this is a really important question. I think what made Holly exceptional was all she endured to escape the rigidity of convention. Most of those Warhol superstars were heiresses from very wealthy families: Edie Sedgwick, Brigid Berlin, Ultra Violet. Holly was from the gutter. She was a 16-year-old kid who ran away from Florida, and that was a hell of a trek. In that process, she transitioned from a boy to this androgynous waif, and even Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis did not experience that kind of journey. But she was also a standout because Holly had a very endearing personality and a great sense of humor. She was warm and compassionate. But ironically, she was also conniving. She was a thief. She did drugs and impersonated a French diplomat’s wife to go into the UN building and withdraw like, $2,000 from her account, which she got away with the first time. Then she decided to go back for another haul and was arrested. So on the night of her big movie premiere, she was in prison. I don’t know of any other Warhol superstar who had that kind of trajectory.

RUSSELL: I love how you two truly were opposites. I mean, you were a small town gay and not at all worldly when you first moved to L.A. And yet you guys struck up this incredible friendship.

COPELAND: We were total opposites. I wanted mainstream success. I wasn’t interested in the avant-garde underground film movement. I also had a strong moral compass. I was the workhorse who would get into the trenches and make things happen. And I hate to say it, but Holly was kind of a mess. God bless her. I mean, I loved her so much, but we were at opposite ends of the spectrum. I would’ve never stolen my mother’s jewelry and hawked it to hop a bus and get to Georgia and hitchhike the rest of the way to New York. I honored my parents. I wanted to make my parents proud, and I know Holly loved her parents, but she was such a little troubled teenager. When Holly turned 16 and discovered the gay beach in Miami, she would steal her father’s car. She had a duplicate set of car keys made. Her and her friends would take his car and go out and party. I would’ve never thought to do that.

RUSSELL: It’s funny how you mentioned that you couldn’t Google people back then because that really comes across in the book. Like, you didn’t realize she had a criminal record. You didn’t know about the sex work and the extent of the drug and alcohol abuse.

COPELAND: I didn’t know. And you know what? I was such a square. I was a real conservative, gay little square. When I first started hanging out with Holly, it was challenging for me to wrap my head around her gender fluidity. For some reason, it bothered me, and I don’t know why that is. Over time, what happens is you become fond of the person, and suddenly it doesn’t matter if this person is a man or a woman—or sometimes a man, and sometimes a woman. It didn’t matter at all, but at first it did. I mean, I would call her Hol’. I don’t even know if I go into that in the book.

RUSSELL: Oh, I think you do. You give a real sense of having had a sheltered life up until that point, and you were experiencing real bohemia for the first time.

COPELAND: Gosh, the idea of being a prostitute was so far from my reality. I love the early chapters in Low Life, when Holly is on the streets, because I’m fascinated with the underbelly. I’m fascinated with the fact that she was doing drugs. I would’ve never thought to do drugs. I only smoked pot once, and I was 24 years old, and it gave me such a sinus headache. I never did it again.

RUSSELL: Another funny thing is there were no cell phones at the time, so Holly would vanish for long stretches.

COPELAND: Yes, that was horrible. When Holly Woodlawn disappears out of your life, what do you do? I actually ran around and knocked on doors at her apartment complex. I got on the phone. I was just connecting those dots on this wild goose chase. And I tracked Holly down in Miami, Florida, but Holly was unstable, right? People kept saying, “Oh, Holly Woodlawn is a mess. Stay away from her.” But I liked her so much as a person that I thought… It wasn’t that I thought I could save her, but I thought I could instill some stability into her life. Because at that time, Holly was 42 years old. What kind of future did she have as a washed up alcoholic Andy Warhol superstar? That was bad news.

RUSSELL: Speaking of which, you did try to get her into AA, but she didn’t stick with it. And the alcoholism did hinder her later on.

COPELAND: Well, it was unfortunate because Holly’s alcoholism led to very bad business decisions. When A Low Life in High Heels came out, it resurrected Holly’s fame. She was back in the limelight again. But when that limelight starts to fade, you’ve got to have a backup plan. I thought Holly’s backup plan was fashion design, because she had gone to school and studied that. But there were other influences, people who told her, “Honey, you’re an Andy Warhol superstar. You don’t have to get a job.” That filled Holly’s head, and she was very easily misguided. Once I was out of her immediate sphere of influence, she just fell down the rabbit hole of self-destruction. I mean, she worked with Teresa Conboy for a while, and that was good. But like I said, other influences just fueled her alcoholism because she was fun. It was so much fun to hang out with Holly and party and drink wine, but it ultimately undermined her in the end. It was heart-wrenching for me to see, so I had to distance myself.

RUSSELL: She did show a real commitment to showbiz, even if it was the absolute fringes of showbiz. She was hustling and scraping and appearing in student films, for example. I think normal civilian life was not of interest to Holly Woodlawn.

COPELAND: Right. But the thing is, what are you going to do for health insurance? What are you going to do to pay your rent? I am all about being creative and being an artist. But if you don’t have someone who can support you—and Holly didn’t—that’s kind of a train wreck. Here’s the shame, the big rub that I think what bothers me most—Holly was so well-connected. If she applied herself and was diligent, she could have had a great career. But she didn’t.

RUSSELL: After Trash, there should have been so many great opportunities for her, and for whatever reason, they didn’t materialize. I mean, we all like to think that Candy, Jackie, and Holly were friends— and they were— but they were complicated frenemies because they were all competing for the same scraps, for the limited opportunities that there were for people like them at the time.

COPELAND: Well, first of all, the shitty truth is, Holly wasn’t a great talent. Her acting was inconsistent. Sometimes she was really good, and sometimes she wasn’t so good. Her singing was the same way. We’d be driving down the street and Holly would break into song, and I’d nearly run off the road because the note she hit was just so ear-piercing. But I think, yes, the opportunities were limited. RuPaul was the one who skyrocketed, and Holly couldn’t compete with RuPaul. There was no way.

RUSSELL: What’s interesting reading Love You Madly is how Holly genuinely was gender-fluid, as we would say today. She would live and dress as a man when life dictated it, and then reassume a female identity when she was able to again.

COPELAND: So here’s what that’s all about. Holly always referred to herself as a woman. “I’m a woman, darling.” She said it all the time. I always referred to Holly in the feminine sense, even when she was dressed as a man. But Holly never wore women’s panties. She always wore men’s Calvin Klein underwear. When Holly was not in Hollywood regalia, she lived as a guy. Holly, because of her androgyny, did not attract gay men. But as a beautiful woman, she attracted straight men with a bisexual itch.

RUSSELL: I know we’ve both read Cynthia Carr’s latest book about Candy Darling—

COPELAND: I love it.

RUSSELL: Candy Darling seems like she was quite tortured about her sexuality, whereas my surface level impression of Holly is that she wasn’t tortured in the same way.

COPELAND: No, Holly wasn’t. What I get from Candy Darling is she was indeed really tortured about having a penis. Holly, I know for a fact, loved having a penis. She never would refer to that as a flaw. And it’s funny because gender-fluid wasn’t a term back in 1988 when we met. Holly really got upset with people because of the way they tried to pinpoint her. They called her a drag queen. She wasn’t a drag queen. She really wasn’t a transvestite. I mean, Holly was just Holly. She got tired of people trying to label her. Sometimes she was Holly Woodlawn, a glamorous Andy Warhol superstar. And then sometimes she was just Holly Woodlawn, the guy who lived next door.

RUSSELL: You don’t really sugarcoat at all that A Low Life and High Heels was very successful, but you two did fall out once big money was at stake with the film rights.

COPELAND: Yeah, something terrible happened. That was the big irony. It was just so unfortunate what happened, because here’s the deal. When Madonna comes out of the woodwork and attaches herself to A Low Life in High Heels, that news goes around the world, and the party invitations were nonstop. Holly was on top, but unfortunately there was so much frustration and disappointment that surrounded the possibility of the movie being made. It just went on for years, and that was too bad. I don’t want to talk too much about it because it upsets me.

RUSSELL: But what I would say is the book ends on a positive note because you two do reconcile before she dies.

COPELAND: Oh my god, absolutely. I remember when Holly did die, and I was telling a very close friend of mine about Holly’s death. Her response was, “Well, do you even care?” It hit me like a knife in the chest that someone would think that I wouldn’t care because Holly and I had been through so much hell, but I never once stopped caring about her or her well-being. My first decent break came when I was 30, and I celebrated by buying groceries for Holly. I brought them over to her house because she was desolate, and it was very painful for me to see what she was going through because of the choices that she made. She had Madonna in her camp, yet she was scrounging around on the street trying to find cigarette butts. It was just horrible.

RUSSELL: It is a warts-and-all kind of portrait, but at the same time, her joie de vivre comes across so powerfully in the book. I love the idea of her as your sort of fairy godmother or Auntie Mame figure. So I’d love to know, what do you feel like she taught you?

COPELAND: Well, the big life lesson is the importance of forgiveness. Don’t hold a grudge, because me and Holly went through some bad shit, but I wanted this book to be a celebration. I look back at my career and none of it compares to the magical whirlwind that I experienced with Holly Woodlawn. She said to me, “Darling, I’m going to be your Auntie Mame.” It was the power of her celebrity. She took me under her wing to the most fabulous parties because she was always invited. When was I ever going to hang out with Bob Colacello or go to Allee Willis’s celebrity-studded parties? But with Holly Woodlawn, I went everywhere. That was the Auntie Mame influence.

RUSSELL: A Low Life in High Heels ends with her giving advice. After she’s lost all of her belongings in a fire, Holly decides all a girl needs in life is a pair of heels and a pack of cigarettes.

COPELAND: Yes, a pack of cigarettes. That about sums it up, because Holly was always smoking nonstop.