ORAL HISTORY

“At Night Was When We Lived”: The Life and Death of Disco Doorman Haoui Montaug

This is a story about the life and suicide of Haoui Montaug, one of the most important cultural agents of the late 20th century. Though you’ve probably never heard of him, Montaug—doorman extraordinaire, poet, activist, writer, and friend to many—was an essential part of the origin stories of so many artists, bands, actors, directors, and designers, from the Beastie Boys to Madonna.

Montaug’s connections were far and wide, and the resurrection of his legacy has been a monthslong journey that took a life of its own, stretching from the still mean streets of New York City to the lush woodlands of South Africa and the hot desert of southern California. The sheer range of contributors to the oral history that follows is a firm testament to Montaug’s electric influence, including actors such as Debi Mazar and Lisa Edelstein, journalists like Diane Pernet and Michael Musto, poets, artists, designers, and even the director of Tiger King.

While this is a story about loss, pain, and sickness, I prefer to think of it as a tale of kindness and generosity, how the human will to survive—and party—transcends societal schisms. Many of the people who spoke to me for this story broke down into tears while recalling Montaug’s infectious spirit. But all agreed that this was a story that needed to be told; not only for Haoui, but for all who were lost to AIDS.

———

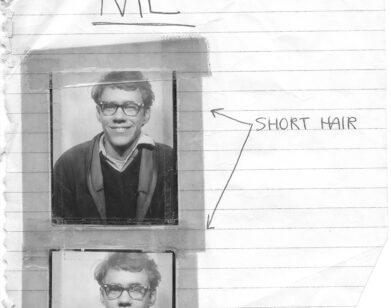

“It’s not like he didn’t try to fit the mold. But he couldn’t.”

CHRISTOPHER AARON BLACKMON: So many people I’ve interviewed about your brother knew him well as an adult in 1980’s New York, but couldn’t speak to his early years. Tell me about your brother. You both were born and raised in Brooklyn, correct?

CARRIE GOTEINER NÉE MONTAUG [HAOUI’S OLDER SISTER]: East Flatbush. Almost four [years apart]. Very small family. We lived on East 51st, between Lenox and Clarkson, so I would walk to school. And when my brother was old enough to go to school, I would walk him. And when my cousin was old enough, he lived around the corner from us, I’d walk both of them, holding their necks like this, as we walked to school, because my cousin was a little rambunctious. My brother was much, much quieter and sedate. We were the first ones, aside from my uncle, to go to college.

BLACKMON: And Haoui ends up going to Boston University…

GOTEINER: Boston University, yeah.

BLACKMON: What was his major?

GOTEINER: Early childhood education. He loved kids. He ended up working at McLean’s, which is a psychiatric hospital. He came out when he was in college. Well, he didn’t come out to my parents until later. I had suspicions for years. My brother was not an athlete. He was effeminate. Back then, you didn’t think about it. He had a girlfriend all through high school, you know, so it’s not like he didn’t try to fit the mold. But he couldn’t.

BLACKMON: What was the reaction like when he came out to your parents?

GOTEINER: It was very interesting because he didn’t officially come out. He was in Europe, and he was writing to me. And David, my husband, was reading one of his letters and left it in the bathroom while my parents were visiting. And my mother read the letter. So that’s how it came out. She was horrified. She kind of knew, but she denied it. And my father, who you think would be the one who would be more upset, was not. But my mother said, “Don’t tell anybody, it’s a secret.” And I said, “Whatever you want.”

BLACKMON: How did you feel?

GOTEINER: He’s my brother. I love him. I didn’t have any issues. [After college] he started traveling all over Europe. That’s how his name got changed to Haoui, H-A-O-U-I. [Before] it was Howard, and people called him Howie, H-O-W-I-E. But when he was in France, they spelled it H-A-O-U-I. I have some of his letters and his journals, so I know that he was in Greece, he was in Amsterdam. He lived in England for a while [in the 70s]. And the reason he was able to stay is because he “got married.” And I say this as a quote, because she wanted to come to the States and he wanted to stay in England. I couldn’t even tell you what he was doing, he was active in so many different things. He was just seeing the world. When he came back [in 1981], he moved into the Bowery in the city.

“He charged Mick Jagger or David Bowie the $6 entry.”

ERNIE GLAM [JOURNALIST AND NIGHTLIFE PERSONALITY]: I have a very distinct memory of the first time that I met Haoui Montaug, because I had just moved to New York City after I graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. One of the things that I was very excited about in moving to New York was the opportunity to go to nightclubs. Almost immediately after I moved in May of 1984, I started going to Danceteria, and the first night I was there by myself because I didn’t know anybody. All of a sudden, this older man, who was Haoui Montaug, walked up to me and introduced himself and said, “Here, why don’t you have a drink ticket? I like the way you look.” I can’t remember exactly what he said. But I thanked him. That was the reason I remember that interaction and meeting him so well, because that was like the beginning of how I learned to work the nightclub system.

DIANE PERNET [FASHION CRITIC]: I think Haoui, if I remember correctly, he charged Mick Jagger or David Bowie the $6 entry. Of course, we never paid to get in.

LISA EDELSTEIN [ACTOR AND ARTIST]: I am pretty sure I met Haoui when he was the doorman at Danceteria. He and my friend Anita [Sarko] had a cabaret show called “No Entiendes” that I just loved. So much weird talent, I found it inspiring. I know I felt safe with Haoui, and that was saying a lot for me at that time in my life. I had gotten very famous for no particular reason, and when the New York Times Magazine did a big piece on me, my phone number and address were listed in the phone book. So I was not only dealing with the strangeness of celebrity, but also with about 40 stalkers. Haoui took me in.

DANIEL MINAHAN [TV AND FILM DIRECTOR]: I came to New York [in 1981] from suburban Connecticut. I got there in the middle of June, and through the Village Voice, found an ad for busboys at Bonds International Casino, which was a club in Times Square. It was an old department store that had been converted into a nightclub, and I got the job. Right away, I realized that there was something kind of sinister about the place. The other busboys described to me how the position had opened up: one of the busboys had been pushed down an air shaft, or fell down an air shaft, I don’t know which one. And I got this kind of a protector who stepped in, Haoui. He said, “Well, you’re not a busboy anymore. You’re going to come and work with me.” He worked the VIP entrance to the club. I was just there to run errands, to buy cigarettes for people who were playing, to do laundry for The Clash. He had me doing a whole bunch of things because I think he realized I was green.

VICTORIA SPENCER NÉE LOCKWOOD [MODEL]: I hate to tell you this, but it’s quite a blur. I had been scouted by Bruce Weber, and he wanted me to come to New York to model. I arrived and how I met Haoui, I cannot tell you, but I was part of the sort of Brit 80s. I started going to the Palladium and got in with this fashion and music subculture of expats, mostly. But something happened with Haoui and I—we became like a couple, which is strange, because he was gay. We even talked about getting married one day because, you know, it could have been useful for him and for me. But we were absolute soulmates. He was very wise and he was very calm and he was powerful, but in a gentle kind of way. And super protective of me; he adored and loved me. And I don’t know how or why, but I became his little protégé. I remember he wore these white thermal underwear and I would hop into the bed and cuddle up to him. He was like a guardian angel.

CATHY UNDERHILL [DANCER AND HAOUI’S ROOMMATE]: I originally decided to go to New York because I danced. By the time I got there, I had really sort of lost interest in that. The other reason I was going was, I heard Blondie and Patti Smith and thought “I need to be there.” And soon as I got there, I kind of landed in the middle of that whole club scene. I ended up meeting a lot of people, and then I met [John], who I ended up marrying, who was Haoui’s roommate. Through John, I became friends with Haoui. That was around 1978, probably. They got a loft together on the Bowery. I thought they were crazy, because it was so expensive. We were all working at the first Danceteria together. When John died, I just moved in with Haoui permanently.

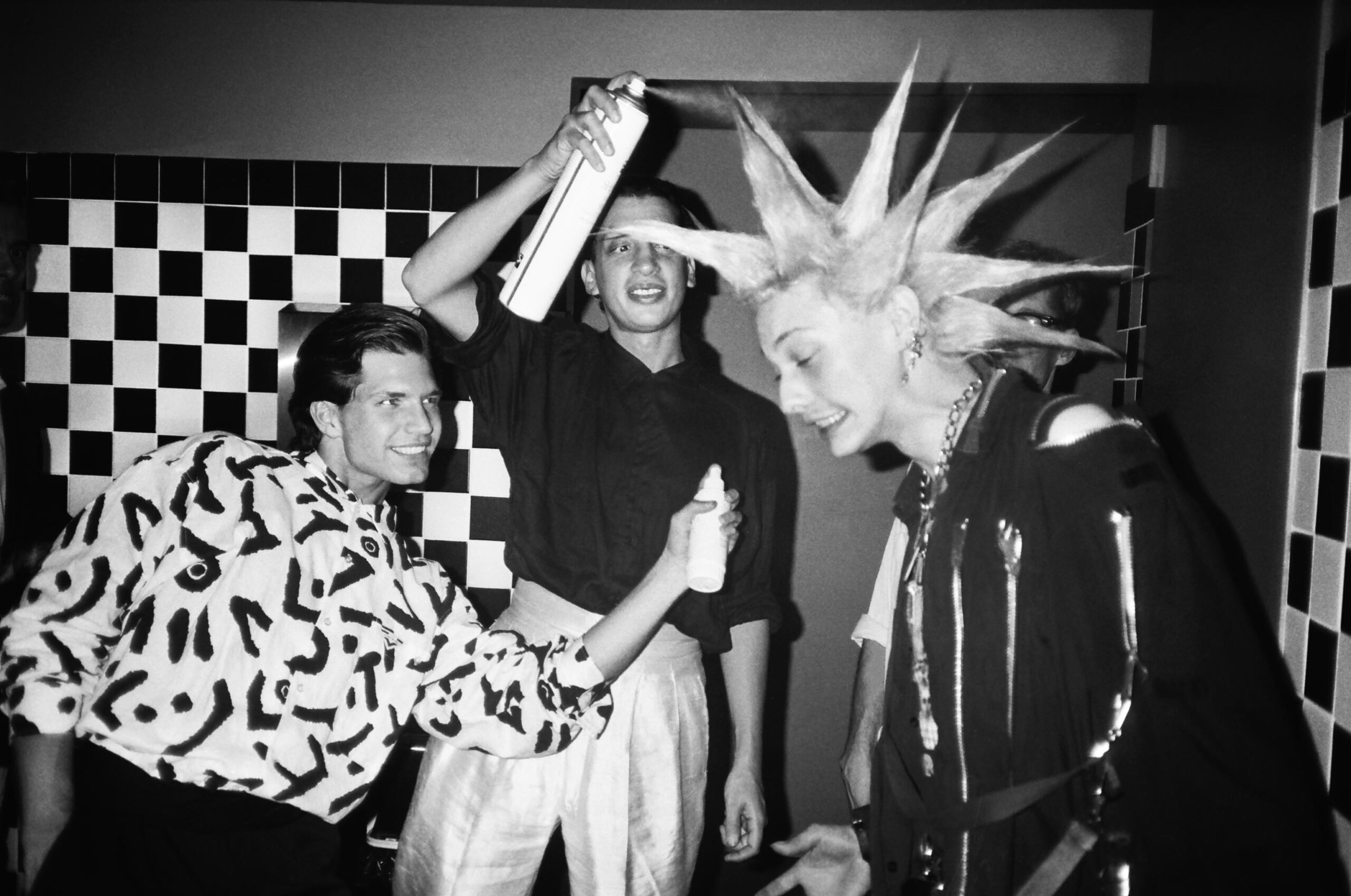

From left: Haoui Montaug, David Russell, and Michael Clancy. Danceteria, NYC. December 1986. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

DEBI MAZAR [ACTOR]: When Danceteria opened, I got a job there as the elevator operator and Haoui and David Russell were the doorman out front. He was wonderful because he had such a great personality. He was an intellectual. And to me, he was like a big brother. I felt like he was the boss, even though he wasn’t. He kept people in line, and he wasn’t a big guy. He was thin, he dressed impeccably. He was really tough.

ERIC GOODE [CLUB OWNER, HOTELIER, AND DOCUMENTARIAN]: Well, I knew Haoui. Not only did I know Haoui, I knew all the owners of all the clubs because I was deeply into that world. There were two Danceterias, one on 37th Street and one on 21st Street. He worked the door there. And that’s where he famously created that little cabaret [“No Entiendes”] and had Madonna perform. I was never a huge fan of that because I always went to Danceteria to meet girls and hang out. I never had the patience to watch performers. Then Haoui went on, of course, to the Palladium, which I think opened in ‘85 or ‘86. Haoui did the door there with Sally Randall.

MICHAEL SCHMIDT [CLOTHING AND JEWELRY DESIGNER]: I came to New York in 1983 from Kansas City and didn’t really know anyone or anything. My only real connection to the community was through bars and clubs, and that’s where I ended up meeting all of my lifelong friends. I met Haoui originally at Danceteria, which was the great club of the time. We just kind of hit it off. And then eventually we started dating…

DIANNE BRILL [DESIGNER AND NIGHTLIFE PERSONALITY]: First of all, Haoui had a fabulous sense of fashion. He always wore a full suit with long shorts, but not like Little Lord Fauntleroy or King Louis XIV. It was very funny. It was part of his shtick. He had a beautiful face—a very unusual face, but very beautiful, and big kissy lips. I always found that we were hugging each other. He was lovely.

MUSTO: I mean, I was a kid from Missouri. I didn’t know anything about anything and he took me under his wing and was very protective of me. You kind of needed that in 1983 in New York City. It was a very different time, a very different place. We started dating later, but he really was the center of the universe for everyone around the scene at that time. New York really had a few touchstone people and Haoui was certainly one of them, but that wasn’t really what drew me to him. It sort of evolved into a natural romance. It didn’t last terribly long, but it was amazing. He was very good at assessing a person’s talents and creativity, oftentimes before they saw it themselves. [It was] like he gave you permission to be something greater.

“He didn’t suffer fools.”

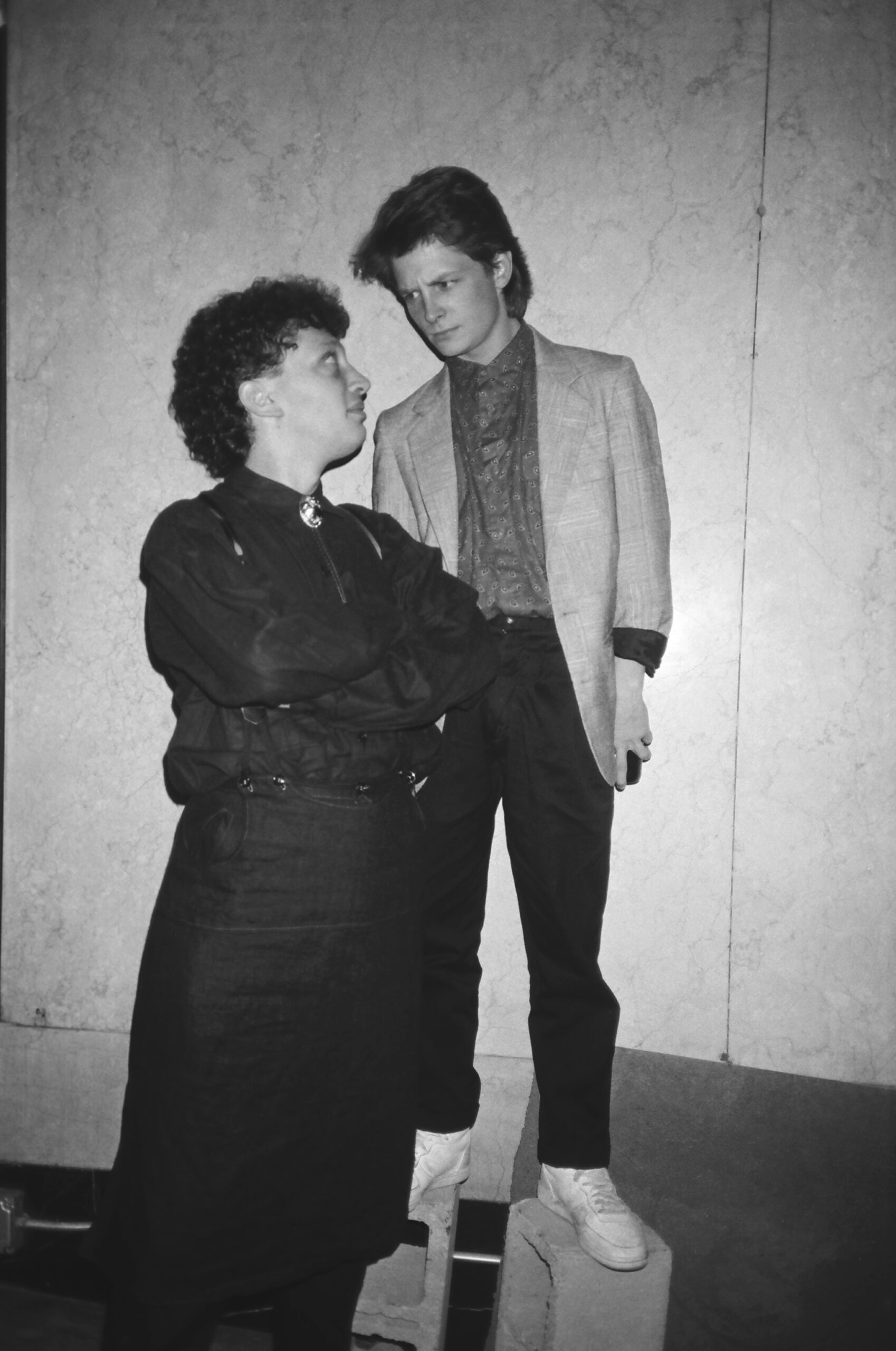

Haoui Montaug and Dianne Brill. William Burroughs Party, Limelight, NYC. February 1984. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

UNDERHILL: It was a time of massive culture shift. Up until then, we had The Eagles. Music was boring. There was something in the air that said, “We really need to change this.” The clubs were meeting grounds of like-minded people who had picked up on the same cultural information and wanted to find it.

MINAHAN: [In New York], I landed this apartment on Avenue C in 1981. You can imagine what that was like, one of those ones with the tub in the kitchen. To me, it was an adventure. But now that I think back, you know, there was some crazy Vietnam vet, who lived upstairs and forced his way into my apartment one night.

BRILL: I came to New York realizing when I got here that this was Oz. I realized I’ve been looking for this place. Am I the right girl in the right place at the right time? We will see, but it sure feels like it. In those days, you could get an apartment. You had an incredible amount of time to be creative because you didn’t have to worry about what your rent would be every month. So it attracted people from all over with great ideas and new thoughts and new looks and new smells. But in all our languages and different backgrounds, we had the unity of this scene of people who went out at night. Because at night was when we lived.

SERGE BECKER [CLUB OWNER, ARTIST]: It was 180 degrees the opposite of Zurich, where I’m from. Zurich was all bourgeois, clean, pristine, perfect. And New York, it was in complete decay and dirty and dilapidated and almost third world-like—dangerous and so exciting. I met my first cockroach, you know. Sex was another part of why it was so exciting because it was just so free. It was a supermarket. I would walk down St. Mark’s [Place] and the payphone would ring. And it’s just some guy on the fifth floor looking down who has the number of the phone booth, offering a blowjob.

GOODE: You have to remember that New York was almost bankrupt in the late seventies under the Koch administration. New York was crumbling and burning. The authorities had bigger fish to fry than to worry about nightclubs in lower Manhattan. The classic cliche sort of gay scene was in the West Village. Christopher Street, obviously, and the Piers, all the leather bars. New York City was the wild, wild west in those days. You could open a club without any permits or law. You know, you could just do it.

SCHMIDT: We kind of bombarded the Lower East side with our creativity, and we could get by because, back then, you could live in New York and not have any money. It was not an easy place to live in by any means. AIDS was just starting to happen when I got to New York, and for a young gay person to arrive then was the worst thing in the world. But it was also one of the last great times. It was one of the most vibrant times in New York City history for all forms of the arts.

Haoui Montaug in the bathroom of Palladium, NYC. June 1985. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

MICHAEL MUSTO [ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALIST]: Back in the day, it wasn’t a matter of just lining up and pulling out your credit card and getting into a club. You had to be picked and chosen. There was something kind of exciting, or demoralizing, about that whole situation. But the door-person was all important because they literally handpicked the crowd. Haoui knew the importance of his job, but he also had a great sense of humor about it. If you crossed him or were obnoxious or didn’t belong there, he could just cut you down with one sentence. He didn’t suffer fools. You couldn’t con him into thinking that you were fabulous if you weren’t really fabulous.

GLAM: Certainly at the time that I arrived in New York in 1984, door people were very important. They wielded a lot of social power. It wasn’t like nightclubs of today, where everybody’s inclusive.The DJ was mixing the music, the bartenders were mixing the drinks, and the doorman was mixing the crowd.

UNDERHILL: Lots of people felt like Haoui was one of their best friends, and they weren’t wrong, except that there were hundreds of them. What he really regarded as his job was to hook people up. You know, “If you want to do this, I know this person who can assist you to do this.” There was this constant exchange of favors for people.

EDELSTEIN: I honestly don’t remember a lot of the 80’s. It was a bit of a whirlwind for me, I just wanted to experience everything. But Haoui’s loft on the Bowery was like a retreat. I remember going to dinner parties there, sometimes even sleeping over. It felt like a big den of people from all walks of life who loved each other. This is, of course, from the perspective of a 20-year-old.

Haoui Montaug and actor Michael J. Fox. Palladium, NYC. September 23 1985. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

GOODE: The Bowery was, in those days, mostly Irish alcoholics. And then it changed towards the middle of the 80s to crack and heroin. That was the Bowery that Haoui lived on: from the alcoholics to the crack to being sanitized by the Giuliani administration. Haoui never really got to see the sanitized part cause he died almost right when that was happening. He lived in the epicenter of downtown New York, right in the middle of everything.

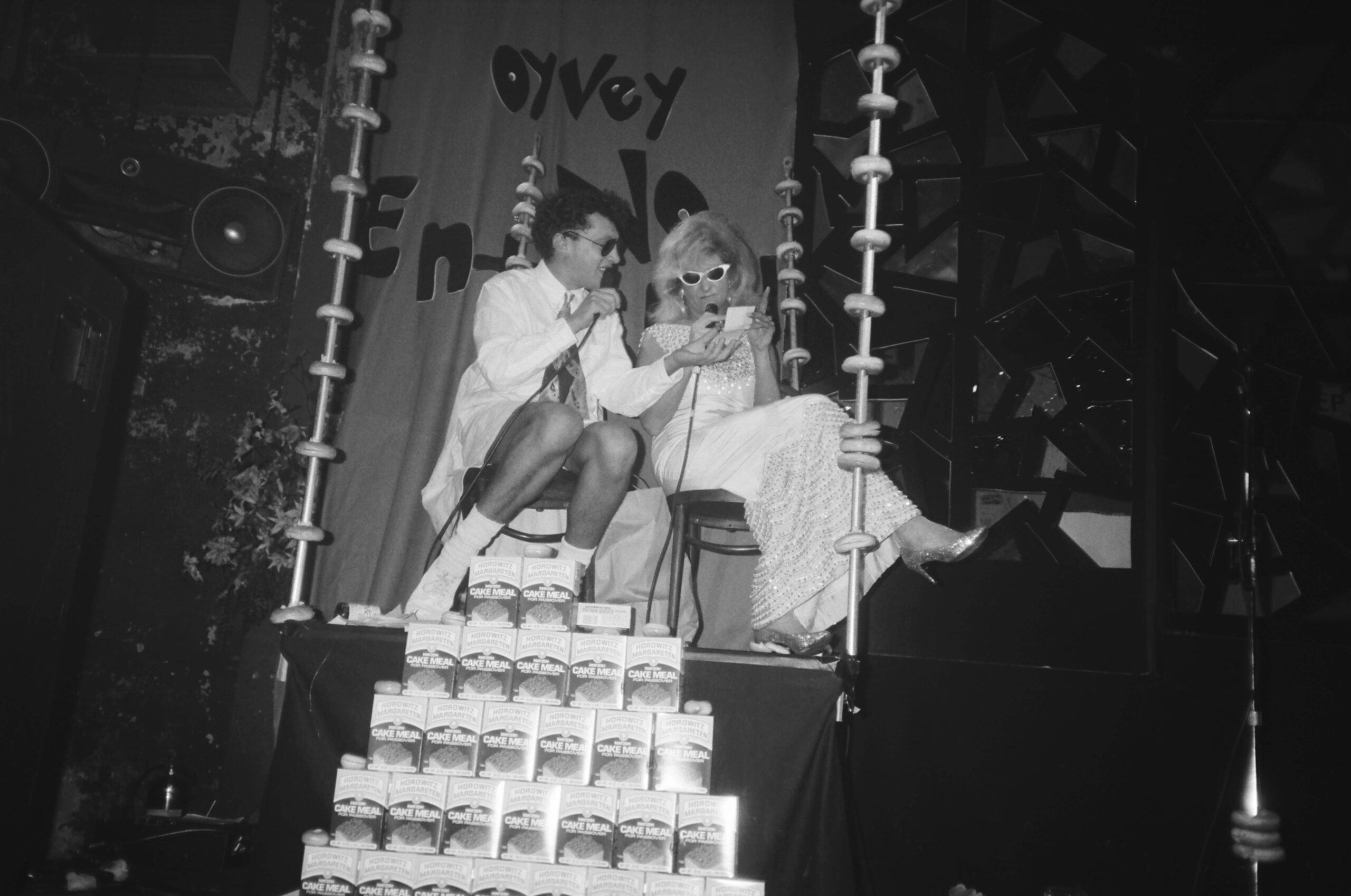

GLENN BELVERIO [JOURNALIST AND PERFORMANCE ARTIST]: Haoui really had a vision of these up-and-coming acts. I don’t think the audience always agreed, but Haoui really had this skill of choosing acts, like Karen Finley and RuPaul. He had RuPaul on stage in 1986. It was right when RuPaul moved to New York from Atlanta, when RuPaul was really kind of punk. But Haoui had this prophetic vision of these DIY homegrown icons; he knew these people were going to become superstars. I remember being at some of those events, and the audiences were really bitchy and cynical. He had a hard time getting people to get excited that Madonna was coming on. They were like, “Who’s this lady? The song sounds really mainstream.” It wasn’t this kumbaya moment; the audience was kind of split.

UNDERHILL: At Peppermint Lounge, Haoui did a show called “I Don’t Know,” which was the precursor to “No Entiendes.” When Peppermint Lounge closed, he eventually relaunched it at Danceteria. It’s always about how he gave Madonna her first show—and yeah, he did. But it was also people doing really dreadful stuff. He let the Beastie Boys do a Hasidic rap, which was one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen in my life. It was definitely performance art. Put seven people in a caterpillar suit and see what happens.

“It was invisible, but it was deadly.”

From left: Calvin Haugen and Haoui Montaug. Limelight, NYC. May 1984. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

MUSTO: In 1982, we saw the first cases of AIDS. It wasn’t even called AIDS at that point. I think people were calling it “gay cancer.” It was so horrific that young people were getting these awful symptoms and dying a quick, grisly death that we prayed it would just go away, that it was just some horrible glitch and would disappear. But it kept mounting and mounting.

PERNET: First, I lived on 873 Broadway, which was across the street from Warhol’s Factory. And then I was living above ABC Carpets in a loft with a boyfriend. But I remember my neighborhood, by 1987, all the clubs were closing.

ANN MAGNUSON [ACTRESS AND CLUB OWNER]: Henry Post had worked at the Soho Weekly News then moved to New York Magazine. Suddenly he got sick, and then we didn’t see him, and then he died. And then Klaus Nomi got sick. And then more people got it. And by the late 80s, panic set in. Like, “Oh god, we’re all gonna die.” When I finally got tested, the fact that I didn’t have it. It was like, “But why am I spared? And all of these people [including] my brother, why are they dying?”

SCHMIDT: It was just starting to happen when I got to New York. Slowly, one by one, people would sort of fall away. I remember one of the first people I met in New York was Martin Burgoyne, who was Madonna’s best friend and very close friends with Haoui. I adored Martin in the limited amount of time that I knew him. And one day, he just was gone. In the beginning, it was very subtle, like a gas that moved through the community. It was invisible, but it was deadly.

KENNY SCHARF [ARTIST]: People started dying, and “free love” abruptly stopped. So here I am, in 1985, and it is kind of fabulous. But at the same time it’s horrific, because I’m often going to visit someone in the hospital. So, this is the life that we were living. We had no choice. It was very bittersweet. It was like, “Well, I want to enjoy all this fabulousness. But I can tell that so-and-so is with us drinking champagne and they obviously have AIDS.” It’s hard to not be able to do anything to help anyone, especially back then. It was tough, I’ll tell you, even just thinking about it.

UNDERHILL: People would try to cover up their Kaposi sarcoma [scars]. That was a thriving industry for a while, makeup artists showing how to cover up your kaposi. In the beginning, everything was kind of going along as normal and people were getting sick. Then, my best friend got sick. I ended up nursing him. And while I was nursing him, Haoui was paying my rent. Maybe I was working one night a week somewhere or something. But, you know, Haoui made it possible for me to take care of him.

GOTEINER: [I hadn’t seen] my brother for a while before, so I hadn’t noticed his complexion was off. He had some of those markings from Kaposi sarcoma, and he lost weight. I am a straight woman, but I am very into following what’s going on in the world. And, you know, I told him to be careful. And he said, “It’s too late.” Because he was promiscuous, you know. He didn’t have one set person, but most of his friends were women. I already had suspicions because of the way he looked that he was ill. Probably a year-and-a-half before he died, he told [my mother and I] when we were at a wedding. I guess he wanted me to be with him when he told my mom.

RUSSELL: He didn’t even tell me right away. We took a trip out to California [in the late 80s] to see a mutual friend of ours and he’d just gotten the slightest sign of KS on his face. We didn’t really talk about it a lot. He didn’t want anybody to be worried about him, or that was my take on it. He continued to work, but then he got weaker. He started to lose weight, and his feet started swelling, and eventually he wasn’t able to work. Also, he no longer had the will to work. That was hard for him, because he was such a social person and thrived on being at every opening, at the door of the best clubs, and hanging out with the most fabulous people at the time. Then, all of a sudden, that became not an option.

“He was going to deal with it on his own terms.”

UNDERHILL: He spent weeks before he died with people coming through the [Bowery] apartment. Like, it was so important to him that people felt okay with his decision. He would spend hours on the phone with people who were trying to persuade him out of it– telling him he didn’t have the right to do that, telling him that he should fight on, trying to make sure that everybody felt OK with his decision. Because he was okay with his decision. When John died, one of the things that [Haoui] said to me was, “Don’t ever let this happen to me. I will not go out like that.” Cut to eight years later, those words suddenly were relevant. I never had any doubt that Haoui knew what he was doing or that he was making this decision based on a split second. When it became clear that he was not going to be well, then he started to say his farewells. [That] went on for literally weeks, people were just coming through the apartment.

SCHMIDT: He decided to take his own life. He tried one night and it didn’t work. He didn’t want to hear it. In fact, it was a betrayal if we said, “Haoui, come on, it’s a sign. There’s so much that can happen.” He was angry and decided that he wanted to take his life. He even said to me, “Look, Michael, if you don’t want to be a part of this, that’s fine, but I don’t want to hear it.” That woke me up because I knew he meant what he said. If I wanted to be a part of that—which I did, of course—then I couldn’t fight him on it. It wasn’t for me to tell him what to do. I really wanted to be there with him. So I was.

PETER NOLAN SMITH [POET AND BUSINESSMAN]: I was in Singapore and called him. I wondered how he was doing. And he said, “Not well. I’m going to commit suicide.” I asked him to wait so that I could say goodbye, but he couldn’t. He described watching The Simpsons surrounded by friends doing drugs. I responded, “I love you. I’ll see you in the future, maybe in my dreams. We’ll always be together in eternity.”

Haoui Montaug and Anita Sarko onstage at “No Entiendes.” Palladium, NYC. October 1986. Photo by Patrick McMullan. Copyright Patrick McMullan.

RUSSELL: Anita Sarko was one of his best friends, and she could not believe that he would even think about doing it. We were all like, “You’ve got to think about this more.” He wasn’t really interested. He wasn’t having it. During that time, he’d seen people, [who] suffered long-term in the hospital, and he wasn’t going to be that person. He wasn’t going to be those people that wasted away in St. Vincent’s Hospital. He was going to deal with it on his own terms.

SPENCER: We wrote letters or we called each other. Because after New York, I moved to Paris, and after Paris, I moved to England. I remember him coming to London and seeing him. I realized that he had the lesions. It was heartbreaking. We never even spoke about it. It’s almost like he couldn’t tell me.

GOTEINER: [I saw him] a couple of days before he died. He knew that it was coming close to the end. He said, “I’m not doing well,” and we made arrangements to see him so he could say goodbye. He wouldn’t want me to be involved. I don’t know if he died of natural causes or not.

BLACKMON: Oh, you don’t?

GOTEINER: No, I know he was very sick. He had accidents, he was losing his self-respect. And he said that he didn’t know how long he could last.

BLACKMON: I do know how he died. It’s very well known in his friend circle. The information is out there. So, I’m just letting you know that it’s well known. Do you want me to tell you?

GOTEINER: Sure, yeah.

BLACKMON: Haoui called several people to say goodbye. He invited people over to his apartment. And he overdosed on some barbiturates. Friends were there to call the police, that’s how that happened. He was in his apartment.

“He wasn’t raging against his fate.”

SCHMIDT: It was cautiously celebratory. We laughed, we told stories, we relived memories. We celebrated his life, and he was in a surprisingly upbeat mood. It was a Sunday. I reached out to a mutual friend of Madonna’s and had her call him. She expressed how grateful she was to him. And, you know, he enjoyed that.

UNDERHILL: I cannot remember what the episode [of The Simpsons] was. I just remember everybody on the couch, huddling around Haoui. I was sitting at the back, watching and thinking, “I cannot believe it’s such a shitty episode.”

MAZAR: I was young, and I had never been around somebody who was about to die by doing it electively. It wasn’t a happy occasion for me at all. I have a memory of him saying “I love you” and going over to him in bed and kissing him. I remember that smile. And then I left because I couldn’t deal.

UNDERHILL: I was seven months pregnant at the time. I don’t remember the next couple of days afterwards, but then we started planning his memorial service. At St. Mark’s Church, we got a bunch of people who had done “No Entiendes” and David and I went out and bought toys to throw into the audience. It was the perfect way to send him off. He would have wanted people to be enjoying his legacy, not crying. Haoui was so clear about what he wanted, and so clear about leaving, whereas most people are not. For some reason, the grief was easier. He wasn’t raging against his fate. He wasn’t angry. He wasn’t miserable. I mean, I’m sure he was. But he wasn’t denying what was happening.

RUSSELL: There were still four of us there and, needless to say, we had to call 911. The EMTs came, and I think that they had become kind of used to scenarios like that. They were compassionate about it. There was no heavy-duty questioning of why we were there or who found him, they could just tell. The pill bottles were there. They collected his body and that was the end. The next day, having been up all night, we were tapped. We were all really exhausted, physically and emotionally. For me, it took a few days for it to all settle in. We were all pretty young, and nobody in my whole circle of friends had ever experienced anything like that at the time, you know? We’d already been through our fair share of seeing people die, but no one in our close circle had chosen to die by his own hand. I often wondered, “Did I not try hard enough to convince him not to do it?” Then eventually, you realize that wasn’t going to make any difference.

SCHMIDT: I still have feelings about the urgency of [AIDS], but there are tools now to prevent it and keep it under control. People view it now as a manageable situation, and I only wish that those medications had come much sooner because maybe Haoui would still be with us.

GOTEINER: When my daughter was turning 16, Haoui bought my daughter an answering machine, the most outrageous phone that you’ve ever seen. It lit up in all different colors, something that only he could have picked out. Right around the time he died, the machine stopped working. I don’t believe in karma or anything like that, but I thought that was very strange.

“Dancing on the lip of a volcano.”

MUSTO: I remember, initially, it was reported that Haoui died of AIDS. I had to tell my editor, “He didn’t die of AIDS. He killed himself because he had AIDS.” They corrected that in The Village Voice.

EDELSTEIN: I’d grown used to this horrible parade of illness. Haoui knew he was positive, but he wasn’t symptomatic for a while. Once the kaposi sarcoma showed up, his attitude quickly shifted. By then, we’d seen so much death. Misery, isolation, no access to good healthcare, no insurance. During the AIDS crisis, I learned quickly not to judge the choice of suicide. It was the only control left for some people. And Haoui was extremely clear on his choices. He was not depressed. He just did not want to go down the road he knew he was on and saw no other possibilities available to him. He didn’t want to put it off. He had a plan, and he was enacting it.

JAMES ST. JAMES [ENTERTAINER]: So much of that period was, you’d wake up every day and you’d get a phone call and hear someone else had passed away. You never got numb to it, but it just became a part of life in downtown New York in the late 80s and early 90s—person after person after person. Your nightly activities: you would go to a memorial service, and then an art opening, then a dinner party, then to a club, and then to an after-hours club. It became a part of everyday life that you were paying respects to someone, and then you’d have to go to a party.

BRYAN RABIN [FILM PRODUCER AND NIGHTLIFE PROMOTER]: When people are sick or dying, there is a smell of somebody starting to decay from the inside out. When you’ve lived through that, all of those sensory things come back to me. I became a nurse; I was changing lines; my boyfriend was dying in the house and we had to keep it a secret. Who’s prepared to do that at 25? It was all shrouded in secret, and it was all shrouded in so much shame and rage. Because those fucking hideous Reaganites—I despise them—they laughed. That moron [Ronald Reagan] did not mention the word AIDS while everybody was dying.

MUSTO: The horror of the situation was that President Ronald Reagan willfully turned a blind eye. He just didn’t care. We were being called sinners who deserved it, that this was god’s punishment. And at the same time, the nightlife was extraordinary. The survivors were kind of holding onto each other for dear life and bonding in the club. It was very important for us to be together every night.

RABIN: 1992 was really a seminal year, because a lot of the DJs started going down. A lot of things are hard for me to remember; my brain did that, I think, for protection. You see that the body is completely ravaged but the human spirit does not want to go. None of those people wanted to go, even if they said they were tired. So we had to keep saying, “We’re going to be sad, but we’re going to be okay.” My boyfriend held on for three days with that death rattle. On morphine and hydration, we had candles going, and we were holding vigil with flowers all over his body. I was laying on top of him when he took his last breath. And it’s not like the movies, I’ll tell you that. When the big exhale happens, they just cease. But I felt his spirit go out the back through me. There are no words to describe what I felt. There’s electricity in our bodies that leaves. I’m not sure what it was, but I will never forget that last moment. I relive that as both a beautiful moment and as a nightmare.

MAZAR: My New York was over after a lot of these people died. It was just a fabulous time, and then it all started changing. I will always love New York, but my New York changed after that era.

JAMES: It’s hard to explain. I think that so much of the extreme happiness and frenzied nightlife was because you were dancing on the lip of a volcano. You didn’t know if tomorrow was guaranteed, so you had to appreciate every minute that you had. Your emotions were sort of up and down. When you were down, you were really down; when you were up, you were really up. I don’t know that you can separate the two when you think about the 80s.

GLAM: The heaviness of AIDS lifted because anti-retroviral drugs emerged in the mid-90s. They helped a lot of people survive. You saw a lot of people die until about 1996 and, all of a sudden, people stopped dying. It just kind of seemed like it went away, even though it really didn’t.

SCHMIDT: In the mid-90s, I saw Grace Jones perform, and she did something that was so astonishing and so beautiful. This was at the Palladium. Midway through her show, she said, “I’d like to stop and take a moment because being in this room brings back so many memories. We’ve all lost so many people, so many great friends and loved ones. I think that we should call out their names.” She started calling out the names of all the people that she had loved and lost, and everyone slowly started to do the same. When I called out Haoui’s name, it was such a profound experience. It was so cathartic to feel the presence of these thousands of people. To feel that they were there in the room, it was a beautiful way for me to remember someone who changed my life.

UNDERHILL: When [my husband] died, I was 23. John’s death was absolutely fucking horrible. One of the things [Haoui] said to me, like pretty much as soon as I got back from London, was “don’t ever let this happen to me. I will not go out [like that].” Eight years later (or however many years later), those words suddenly were relevant. I never had any doubt that Haoui knew what he meant. This was something that he had thought about. He had decided what was acceptable for him and what was not acceptable.

RANDY BARBATO [CO-FOUNDER, WORLD OF WONDER]: Just sitting here, thinking of anyone who was at the point that they were so sick and made the choice to end their lives, I salute them. They made the choice to live their lives out loud. And, you know, I don’t judge. I don’t judge anybody who was on their deathbed and made the choice to end things on their own terms.

SPENCER: I came back to New York to attend Haoui’s memorial and there were hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people there. I remember staying in the Mercer Hotel and crying my heart out. I think he’d be proud of me now that I’m clean and sober and I’m living a good life. I think he’d be proud that I’m still alive, actually. Haoui would still be in my life today if he hadn’t gone. He still is in my life, in a way. I could have married Haoui. He asked me to marry him, you know. I wish I had.

GOTEINER: I think of him often, what he would think about this situation or that. He said something to me that I think is very important. He said he had no regrets. He lived more in his 39 years than most people live in a lifetime, and I keep that with me all the time. I never think, “Why did this happen to him?” Because what’s the point? It’s not going to bring him back. So when I think of him, I just remember the good.