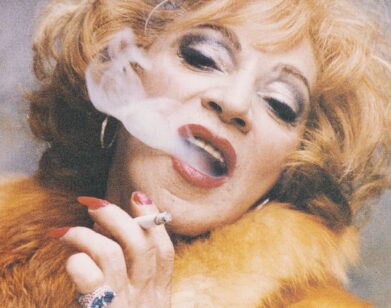

Tao Lin

ABOVE: TAO LIN IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2013. STYLING BY MIGUEL ENAMORADO. JACKETS: BLK DNM AND CALVIN KLEIN JEANS. PANTS: CHRISTOPHER KANE X J BRAND. GROOMING PRODUCTS: BUMBLE AND BUMBLE, INCLUDING STYLING LOTION. GROOMING: KENSHIN ASANO FOR BUMBLE AND BUMBLE/L’ATELIER NYC.

On Easter Sunday this year, 29-year-old novelist Tao Lin is playing a slot machine at Resorts World Casino in Queens, betting the maximum amount on each spin. In the parking lot outside the casino, Lin took 10 milligrams of Adderall, and now he’s trying to lose all the money he has in the slot machine so we can begin this interview exactly 30 minutes after he took the drug, which is when, he says, he’ll be at his most effusive. In five minutes, he loses his $20 and smiles, so we walk around the casino, looking for a quieter place to speak.

Lin is unquestionably one of the most loathed young novelists in America today. He grew up in Orlando, went to NYU, and has released five books since 2007: a story collection, a volume of poetry, a novella, and two novels. He has attracted an army of vocal detractors because of the self-promotional tactics he uses to attract attention and make a living (a few of the more salacious examples include publicly cataloging his drug use, e-mailing Gawker to ask them to write about him, and releasing Bebe Zeva, a 2011 feature-length documentary shot with his MacBook’s camera). What he embodies is what the old both hate and envy about the young: a belief that every little thing that happens to them will be of interest to everyone. Lin tweets things like “Person averted their sight as I walked absently up a down escalator while maneuvering my iPhone so the display wasn’t sideways/upside-down,” and his books are written in a variant of that style.

Lin also has evangelical fans. He’s attracted a following of eager acolytes who write in a similar vein and buy the items he sells online: recorded conversations with himself, bits of art, things from his apartment, sundries he has shoplifted. (He estimates that he has sold around $10,000 worth of stolen batteries.) Miranda July called his work “moving and necessary,” and Bret Easton Ellis recently tweeted about Lin’s next book, Taipei (Vintage), out this month, “With Taipei, Tao Lin becomes the most interesting prose stylist of his generation, which doesn’t mean that Taipei isn’t a boring novel.” Through the stream of mundanity, Lin’s writing is hypnotic, tragic, hilarious, confounding. Taipei is a thinly disguised work of fiction that parallels the past few years of Lin’s life: his book tour, his trip to Taiwan to visit his parents, his shoplifting, his drug use. It’s aggressively robotic, but also heartbreaking. His previous book, 2010’s Richard Yates, about a 22-year-old Manhattan author and his girlfriend, a 16-year-old high school student living in New Jersey, is the only book I can remember that brought me to tears.

After Lin loses his $20, we walk through the casino as he takes photos with his iPhone and occasionally giggles at them. He’s 5’8″ and wears a pair of black dress shoes, ripped black pants, and a crewneck sweatshirt. It’s comforting to be around him because he seems incapable of anger or reproach. Even though there’s a constant stream of fury leveled publicly at his writing and at him personally, I’ve never heard or read him say an unkind word about anyone. I’m jealous of a few things about him, but this trait especially.

Three minutes before half an hour after Lin took the Adderall, we get a table at the steakhouse in the casino and order dinner. He notes that the chicken is the only organic item on the menu and orders it.

TAO LIN: I want to wait for the Diet Coke. I feel like I want the Diet Coke to be here before we start.

DAVID SHAPIRO JR.: All right.

LIN: It would probably be good to ask me questions that don’t require a lot of thinking, you know? Things with concrete answers, like “What did you do today?” “What blender do you have?” “What did you eat today?” “What’s a memorable e-mail you’ve gotten in the last week?”

SHAPIRO: [laughs] Why?

LIN: Because I really want to get it right. [Diet Coke arrives]

SHAPIRO: I’m going to ask you questions that may be invasive. You can answer them in any way you think appropriate.

LIN: Okay. I’m going to try to be funny.

SHAPIRO: You’re very frank about almost every aspect of your life: drugs, money, sex, etcetera. You don’t seem susceptible to feelings like shame or embarrassment. What kind of question would make you embarrassed or uncomfortable?

LIN: Uncomfortable? Just, like, if you asked me a question involving other peoples’ information. I don’t know if they would be okay with me talking about them or not.

SHAPIRO: Nothing personal about yourself?

LIN: No.

SHAPIRO: I saw you recently tweeted a screenshot of your bank account balance, which was, like, negative $1,300 or something. How did you get it that low? Don’t they stop at or around zero?

LIN: Well, I sent a $1,200 check for my apartment maintenance. I guess that went through. And I already had, like, a negative-$100 balance, so it went down to negative $1,300. I’ve just been waiting on two checks, like around $5,000 each, for a month or something. Every day I’m thinking, “It’s gonna come today.” The checks are from my literary agent for sales of my book to the U.K. and France.

SHAPIRO: Tell me about what you’ve done so far today.

LIN: I woke up around 3 p.m. That’s about average for me. I go to sleep around 6 a.m. or 7 a.m. And then I ate, like, 30 oranges. Or not 30—like, 10. Small clementines.

SHAPIRO: Is that normal for you?

LIN: Yeah. After that, I went on Facebook to sell some early drafts of my book, because I wanted money for the casino. I think I’ve made like $200 so far. After I sold the stuff, I wanted a vegetable juice because I feel more energized and healthy if I have that, so I took a cab to Organic Avenue on 9th Street and got the juice and a coffee. I drank the coffee while I was on the train to come meet you.

SHAPIRO: Tell me about your financial philosophy.

LIN: It seems like for the last 10 years, I’ve just been investing in the future. Like, any time I get any amount of money, I take taxis and stuff. I just think, If I take this taxi, I’ll save 10 minutes. And in 20 years from now, I’ll be able to make, like, $1,000 in 10 minutes. Or $100. But now it’s only going to cost me three more dollars to take a taxi than to take the subway. I just keep investing in the future, and I haven’t reached the point where I’m not doing that.

SHAPIRO: When were you last supported by your family?

LIN: They paid for college and then gave me money for Christmas and stuff. The first five years, they’d give me $1,000 on average for Christmas and my birthday. But after that, they started giving me less. My brother gives me, like, $300 every year. My brother and my parents also own my apartment, so I only need to pay $526 or something every month for maintenance.

SHAPIRO: What do your parents do?

LIN: It seems like they just hang out around the house.

SHAPIRO: Professionally.

LIN: They’re retired now, but my dad was a physics professor at a college in Orlando. He also started three different companies over the last 20 or 30 years, related to laser eye surgery. He invented one of the techniques for using lasers to correct nearsightedness.

SHAPIRO: Do you speak to your dad?

LIN: We e-mail, like, once every three to five months. Usually, he’ll e-mail me something funny and aloof. He’ll talk about the dog they have: “The dog has been eating a lot. It bites me at night.” And then, like, a non sequitur. Or that will just be the end of the e-mail.

SHAPIRO: Do you reply?

LIN: Yeah, I’ll just be like, “That’s funny.”

SHAPIRO: What does your dad think of your writing?

LIN: One thing I remember is that he read one of the stories in my story collection Bed, from 2007, and in the story, the person goes to a Leftover Crack concert, and it quotes their lyrics, specifically their song called “Fuck America.” My dad e-mailed me, “You can’t say that,” or “Don’t say that.” At other times, he’s said, “I just don’t get it.”

SHAPIRO: Tell me about your first job.

LIN: It was delivering pizzas at Domino’s. I was 17 maybe. I liked it a lot. Just driving in the nice weather and listening to music.

SHAPIRO: What were the advances for each of your books?

LIN: Every book before Taipei was between $500 and $1,500. Taipei was $50,000.

SHAPIRO: Did you expect it?

LIN: The way bigger advance? Yeah, because before this book, I didn’t have an agent, and all of the books except one were with Melville House, a small press.

SHAPIRO: Why didn’t you have an agent?

LIN: When I started I had an agent, but he couldn’t sell Bed. He sent it to 20 editors or something. So we parted ways. But did I expect $50,000? Yeah, because it doesn’t seem like more than I should get. It just seems average, like what I should get.

SHAPIRO: Did you find the New York Times review of your last book, Richard Yates, hurtful?

LIN: No, I felt it was expected. [pauses] But I was almost shocked that the review ended with a line like “By the last 50 pages, when a character said they wanted to kill themselves, I knew exactly how they felt,” which just seemed shockingly insensitive, because the characters in the book are suffering big time. One of them is eating a lot and throwing up every day, and she lives with just her mom, who has another child who is going missing all the time. So it seemed insensitive for the reviewer to say that. It was, like, a punch line. I mean, I don’t know … After some thought, it seems normal. That’s how people are.

SHAPIRO: When was the last time you cried?

LIN: I don’t remember, but I have a note on my phone: “Times I’ve Cried in the Last Year.” [pauses to look at note on phone] I cried when my ex-girlfriend sent me a text message saying how much she liked my present to her.

SHAPIRO: What was your present?

LIN: It was a book I made about her. I spent a lot of time on it and she seemed extremely happy. Oh, and the movie Looper. Whenever Bruce Willis and his wife or girlfriend were in bed together, I’m not sure if I cried, but I had to try really hard not to. And when Joseph Gordon-Levitt said, “Then I saw it …” and he was talking about how bleak the future was going to be, and then he killed himself, I cried then.

SHAPIRO: Tell me about your marriage. And tell me if I’m going too far.

LIN: Oh, no, no … I had known about Megan on the internet since, like, 2008, and we’d talk sometimes. Then I met her in person and we started hanging out a lot, and one night it was really cold here and we were like, “We should go somewhere warm.” So we decided to go to Las Vegas, and it was even colder there. One day we saw a sign for a marriage chapel, and one of us was like, “We should get married.” And we were like, “All right, let’s do it.”

SHAPIRO: Did you think it would last?

LIN: No. We were talking about how long it would last, and we estimated five months.

SHAPIRO: How long did it last?

LIN: Probably six to eight months? But we’re still married. She looked into it, and you have to pay money and go somewhere to get a divorce.

SHAPIRO: Was it a stunt? You broadcast it so much on Twitter and in your writing online …

LIN: It was a stunt between us two in a way, but not with the outer world. It was just funny. I don’t think it meant anything to either of us. She’s had another relationship begin and end since then. And so have I, I guess. We still talk through e-mail sometimes—just, “Will you sell me Adderall?” or something.

SHAPIRO: What would you estimate the cost of your drug use is monthly?

LIN: The last year, probably on average $300 a month.

SHAPIRO: How often do you use heroin?

LIN: The last two years, probably 25 times. If I’m with a girlfriend, after using it we want to just sleep. That’s usually the situation. It feels good to sleep on it.

SHAPIRO: Have you had any unsettling experiences with drugs?

LIN: One time, three months ago maybe, someone else’s drug dealer came to my place, and he had a lot of different drugs. He said one was crystal meth, so we bought it. It was just me and two other people, and we used it. I was expecting to have more energy, but instead I couldn’t move and was face down on my bed. I kept telling the other two people, who seemed like they weren’t as affected, that I thought I was going to die, but they didn’t believe me. They thought I was being lazy, just laying there. But then I was fine. I think it was ketamine. And then just two times when I’ve taken too much heroin, I’ve thrown up for a long time. That’s it I think.

SHAPIRO: Do you believe you’re depressed?

LIN: No. I don’t have a definition for depression. I’m productive, and that’s not a sign of depression, right? And I don’t have weeks where I don’t leave my bed. It seems like depressed people have those.

SHAPIRO: Are there aspects of your life that you would not commodify?

LIN: I would have to look at each instance. But I think mostly the commodifying comes after I’ve done something that has some other value to me. That’s why I don’t have any money, haven’t had money for so long. Does that make sense? Like, I look at what I’m already doing, and then I take that thing and try to make as much money as I can from it.

SHAPIRO: If you were offered a well-paid job and its only stipulation was that you could not write, would you take it, or would you continue to do what you do?

LIN: If I thought that in the long term I would be able to write even more if I did it, then I would do it.

SHAPIRO: What other jobs would you take?

LIN: I don’t really know. I like part-time jobs in restaurants. I don’t know … Because I feel like I’m troubled by my life a lot of times.

SHAPIRO: Why?

LIN: Just, like, it seems like for the last five years, the goal has always been to gradually reduce drug use, get into a relationship that will last, and get a mind-set where I feel like I’m happy or something.

SHAPIRO: Are you happy?

LIN: It seems like I’m not. Because if you look at my tweets and what I think and say, it seems like I’m worried about what’s going to happen. For instance, regarding drugs: just the existence of drugs seems troubling to me. And then it seems like time is starting to move faster. It just seems like I’m moving really quickly towards death while not becoming happier. So that’s something to look forward to, to see what that’s like. But I’m not confident that it will make me happier. But at least it’s something different. And then there’s the thing with my writing where I don’t feel good repeating myself. I just don’t feel good if I’m repeating myself. So that’s getting harder to navigate.

SHAPIRO: How does your new book reflect that?

LIN: It takes the prose style that I used in my first two fiction books, and that I used in my story collection Bed, and puts it into a novel. I haven’t done that before. And it’s the first novel where I talk about drugs a lot, and it has passages about what I think about death and stuff. Basically, it’s just really bleak and depressing. If I want to write another book, I will want to write about my life, but I don’t want to keep doing that. I feel like I need to change my mind-set gradually into something else, like someone who is in a long relationship and seems happy.

SHAPIRO: Tell me about teaching your creative-writing class at Sarah Lawrence College. Did you enjoy it?

LIN: No. The class was called “The Contemporary Short Story.” It was really hard because I’m a shy, nervous person, and because I don’t like teaching with “terms.” I didn’t teach them, like, “This is first person, this is second person, this is foreshadowing,” or whatever, so no one probably felt like they were learning anything. But I feel like teaching in that way reduces the concept to a term.

SHAPIRO: How were your student evaluations?

LIN: Maybe half of them liked me.

SHAPIRO: And the other half?

LIN: Thought I was completely incompetent. There would be long silences during class that were my fault. I’d be like, “All right …” and a long time would go by. And I’d be like, “This is my first time teaching,” and I just wouldn’t know what to say. Like, “Did you guys like this story?” Someone, in the evaluations, said that it seemed like I didn’t have a wide knowledge outside of short stories, and they thought I should. I remember one time the person who wrote that evaluation started talking about Aztec poetry, and I was like, “Yeah, I think I’ve heard of that,” but I guess since I didn’t know a lot about it he didn’t like that. A reporter at the New York Observer e-mailed to ask if she could sit in and observe a class. I was like, “I’m not sure this is right or if it’ll be good,” and finally she convinced me. I remember she said, “This will be good press for the school,” which seemed right. And then she wrote an article that made me look like the worst teacher, like I was mean to the students. And the thing I liked the least was that it made it seem like I was shit-talking George Saunders. I wasn’t. Then the class found out about the article, and some of them were really angry, and I wrote a string of really long e-mails apologizing. I probably should have asked the class. And then there were about five more classes after that. Those were really hard. Two or three of the students would have excuses like, “I’m going to see this person read. I won’t be in class.” And I immediately wanted to explain to George Saunders that I like his writing a lot and that the article was inaccurate in making it seem like I didn’t, but it took five months for me to write to him. I e-mailed him two weeks ago, and he was nice. He was like, “I get it. Journalists do that.” But the article—I should have expected it to be what it was—it talked about me eating Adderall off the floor of the train. When the Adderall fell on the ground, I picked it up and ate it, because I was going eat it. I would put that in an article too, because it was funny and notable and stuff, but it just reflected horribly on me as a teacher.

SHAPIRO: What else do you regret doing?

LIN: I don’t think I understand the concept of regret. Because if I regret anything, that would mean, like, I hate myself. Right?

SHAPIRO: But aren’t you saying that you regret agreeing to the Observer story?

LIN: I don’t regret it; I just think if it happened now, I would do it differently. But to engage with feelings of regret would … I don’t understand how I would do that. Because that would mean that that action affected how I am today in a bad way, so I need to, like, fix something now. It just seems too complicated. I don’t know how to incorporate regret. But I’ll say, like, “It affected me that way,” “I learned this,” “Next time maybe I’ll do it differently.”

DAVID SHAPIRO JR. IS A BROOKLYN-BASED WRITER.

To read about 10 of Tao Lin’s favorite things, click here.