Rula Jebreal

i was having lunch with the mayor of rome, and he told me, ‘A man came to my office, he was wearing pajamas and asked me to turn all the lights off.’â??Rula Jebreal

Julian Schnabel’s latest film, Miral, is a coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle in the decades following the Arab-Israeli war of 1948 and the establishment of Israel as an independent state. Based on the semiautobiographical novel by Palestinian journalist Rula Jebreal, the film explores the human side of the conflict through a narrative that spans both decades and generations: The first half of the film, set during the postwar period of the 1950s and 1960s, chronicles the real-life efforts of Hind Husseini (Hiam Abbass), a member of a wealthy Palestinian family, to establish an orphanage in East Jerusalem to house and educate children left abandoned by the fighting; the second half, which is set between 1973 and 1994, delves into the life of Miral (Freida Pinto), the young daughter of a local imam (Alexander Siddig), who is sent by her father to live at Husseini’s school following her mother’s suicide. Like the book before it, the film artfully sketches Miral’s political awakening as a teenager coming to terms with both her identity and her independence as she struggles to reconcile the more benevolently intellectual influences of her father and Husseini with the more revolutionary ones that have come to surround her—including her boyfriend, Hani (Omar Metwally), whose involvement with an insurgent group responsible for a series of car bombings draws Miral, both physically and psychologically, onto the frontlines of the conflict.

Though Miral, the book, is technically a novel, many of the details of Miral’s upbringing are Jebreal’s as well. Born in Haifa, Jebreal was raised in East Jerusalem. At the age of 5, she and her younger sister were brought to Dar El-Tifel by their father, an imam at the nearby Al Aqsa mosque, following their mother’s death. Schnabel’s film, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival last September and hits theaters this month, both dramatizes Jebreal’s book and elaborates upon it, knitting together the narratives of Miral and a number of other women in her sphere—Husseini; Miral’s troubled mother, Nadia (Yasmine Al Massri); her friend Fatima (Ruba Blal), who is imprisoned after participating in a terrorist attack; her cousin Samir’s Jewish girlfriend, Lisa (played by Schnabel’s own daughter, Stella)—as they wrestle with both the burdens of history that have been thrust upon them and the increasingly complicated and violent world around them.

Though many of the early reviews of Schnabel’s Miral focused on its reflection of the still fraught geopolitics of the region, the film, like the book before it, is more personal than polemical—a feeling intensified by the relationship between Schnabel and Jebreal, who in the course of bringing the book to the screen, saw their creative bond become a romantic one as well. The 37-year-old Jebreal has since relocated to New York City and is currently at work on a new book—her fourth—on the power dynamic that exists between politicians and the media. Interview’s chairman Peter M. Brant recently spoke to Jebreal about transforming Miral into a film and her own coming of age—as a Palestinian, as a woman, as a journalist, and as a newly transplanted New Yorker.

PETER M. BRANT: I wanted to start by talking about your background. What was it like for you as a young Palestinian woman born in Israel? I know that your father worked in the Al-Aqsa mosque, which is one of the greatest mosques in Islam and one of the oldest in the world.

RULA JEBREAL: My first memory as a child growing up is of playing in the gardens, the mosque is really a gigantic garden, probably the biggest in all of East Jerusalem. Our house was about 100 meters from the mosque. When the big doors opened in the morning all the children from the neighborhood would play there. The garden lead up to huge stairs, we would run back and forth while the guards chased us—sometimes, we would pick flowers or climb a tree, they didn’t like that, because it was a holy place. Aside from the fact that he was one of the imams who guided the morning prayers, my father was also the gardener, that was his meditation. We used to go there and help him bring the plants from one place to another. He took us to the markets to select seeds. My whole childhood was about being in that place. It wasn’t really a religious place to me. The love I felt there . . . was in contradiction with what I saw in the streets. It was a different world.

BRANT: As a young woman, what were your own feelings toward the Israeli authorities?

JEBREAL: I didn’t really have any when I was very young because I was protected behind the walls of my house, the walls of the mosque and later, walls of my school. I didn’t know that I was Palestinian. I knew that I was a girl, but the identity issues came later when I was 12 or 13—then, they came in a very strong way. You start questioning yourself: Who am I? Where do I belong? Where am I going? Why is my city divided? Why are we not allowed to enter in certain areas? We used to ask my father why the Christians lived in another neighborhood and didn’t come to our neighborhood. I think my father was trying to avoid having us think about these issues. I think the first time I really felt that I was Palestinian was a time when I was trying to go back to school with my father at night and there was a curfew for Palestinians. My father said, “I will walk first, but you have to understand, the police will not let me go. They will not let a man go, but they will probably let a young girl go, so keep moving and don’t look at me and don’t look back.” When I asked him, “Why won’t they let you go?” he said, “Well, there’s a curfew today for Palestinians.” I asked, “What’s a curfew?”

BRANT: You were 5 years old when your father sent you to Dar El-Tifel, which you describe in your book and which we see in the film as not only a home for all of these displaced children, but also as a great educational institution. How much contact did you actually have with Hind Husseini? She’s one of the strongest characters in the book.

JEBREAL: When I was a little girl, I didn’t have much contact with her—not until I was 10 or 11. But we knew she was there. She used to come to our rooms, to our classes. But I didn’t have a personal relationship with her until later on.

BRANT: She was from a very wealthy family.

JEBREAL: She was from one of the wealthiest families in Jerusalem. . . . The beauty of this woman . . . When Hind asked people to help her with the school, she would always say, “What kind of country do we want in the future? The best resistance is these children. Investing in their future is investing in your own future. If we have our own country one day, then we will have educated people to run it and not ignorant fanatics.” Hind was terrified of the idea of that.

BRANT: As you described in the book—and Julian shows in the film—she started the school during the conflict in the ’40s after finding this group of 55 children in the streets of the Old City who she took in.

JEBREAL: When you go to the school today, there’s a stone where she wrote, “In 1948, I found 55 children in the street. The smallest one was 2 and the biggest one was 12. I decided that day I would take care of them, that my house would become their home, and either I will live with them or I will die with them.”

BRANT: Your father actually knew her?

JEBREAL: Very well. They were friends. He used to bring her children from the city and the other villages. Because he was an imam, people viewed him as a kind of authority—a religious advisor—and they would come to him with their problems. So when they’d find kids who were displaced, they’d come to him. My father would take them to Hind, they would drink tea together and talk. He respected and admired her.

BRANT: He must have if he eventually turned you over to her.

JEBREAL: Well, even though my mother had died and he knew he would be lonely without us, in his heart he felt we’d be better off in a different environment.

BRANT: You lived there basically throughout the late-’70s and the ’80s, right?

JEBREAL: I stayed there until ’93. I was 16 when my father died, and I had a choice to come back and live in his house—my sister was living at my father’s house and my aunt would take care of us—or I’d stay at the school. But I felt if my father wanted me to go to that school when I was 5, there must have been a reason—and I understood that reason when I was a teenager, because that school became the only place where I was safe. As a woman, you don’t have really much freedom of choice in the Middle East—very often, by the time they are 13 or 14, girls get married. What Husseini did with that school is gave women freedom of choice. She gave us another option.

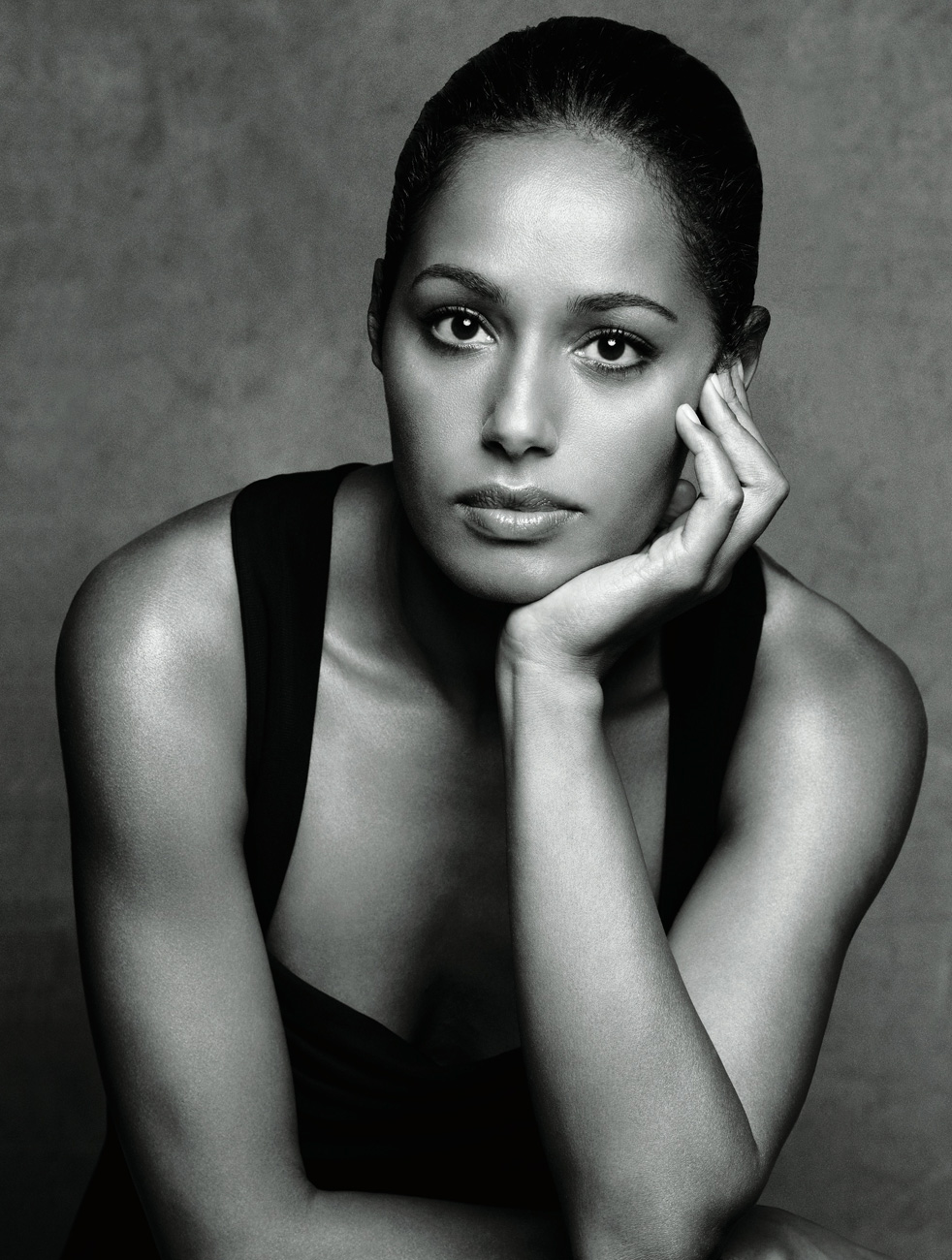

Photo: Rula Jebreal in New York, September 2010. Dress: Azzedine Alaïa.Cosmetics: Aveda, Including Petal Essence Eye Definer In Black Orchid. Hair Products: Aveda, Including Smooth Infusion Glossing Straightener.. Hair: Didier Malige/Bryan Bantry. Makeup: Virginia Young/Streeters. Manicure: Megumi Yamamoto For Rossano Ferretti Ny/Susan Price, Inc.

“i was with my friend and we heard shooting. i was terrified. we were hiding behind a trashcan and the noise was so loud i could only hear my heartbeat.”Rula Jebreal

BRANT: Your father was also an enormous influence. In both the book and the film, he emerges as a very solid figure. There is a strength to him—and also a solitude. But there’s also a lot of love.

JEBREAL: And also a lot of tolerance. My father’s biggest achievement with us as children was that he taught us that everyone is human and equal, even your enemy has the same needs and wants that you do: understanding, love, inclusion. The fact that he loved my mother without judging her . . . What happened to him was even worse than what happened to me as her daughter. She was his wife, but she was promiscuous. She drank alcohol. She insulted him. She insulted all of us. But he loved her. Despite it all, he tried to help her right up until she died. He thought that he could save her—and I understood that. But he couldn’t. At least he gave her the gift of a family.

BRANT: The kind of dysfunction that you had going on in your family, and then to have tragedy hit when your mother took her own life, could have set you off down a very dark path. But it obviously inspired you to go in a different direction.

JEBREAL: I got that impulse from my father. He was my mother’s home, the one place that she knew she could be safe. It was all a journey of faith for him, and I think he felt like if you don’t find more love and understanding at the end of a journey like that, then you are lost—and if you only find hate and resentment, it will destroy you. I believe that.

BRANT: When you were a teenager, you wound up coming in contact with some more revolutionary minds—some people who were more interested in attaining equality or advancing their cause through the use of force and grabbing what they felt they deserved. How did you react to that?

JEBREAL: Well, everybody in my neighborhood was involved. Everybody. But it didn’t start in a violent way—it started out as a pacifist movement. In the beginning, we would sing and make speeches about what we thought was right for our country, about freedom and democracy. It was all about our dreams. But the Israeli military response was so tough that the violence escalated. Everybody where we lived, though, was involved in one way or another. I remember one day, when I was 17, I was with my friend and we heard shooting. I was terrified. We were hiding behind a trashcan and I remember that the noise was so loud that I could only hear my heartbeat. That was my first time at a manifestation but we got used to it. After my experience there, I became a pacifist.

BRANT: Who was responsible for making the decision that you would leave the region and go to Italy on your own?

JEBREAL: Me. I went to Mama Hind after my father died. She said, “What do you want to do with your life? Would you like to study abroad? You will go away for a while and come back, and you will have more

distance.” I said, “Okay.” I didn’t believe that would happen, but then she called me one day and said, “You’ve been selected for a scholarship in Italy.” Soon after I left.

BRANT: Was it her who suggested you go to there?

JEBREAL: No. The European countries used to give scholarships to students in the Middle East. That year it was Italy.

BRANT: When did you start working as a journalist?

JEBREAL: I got my first job, at Il Messaggero, in ’99. It was a privilege to even get this job. When I was hired, the director of the paper said, “Listen, if you even get to write, it will be a big deal—and don’t expect front page or anything like that. You should be very happy if you are on the 10th page.” I did a story about drugs and universities—how students buy drugs, where people sell them. That was the first article I wrote. Eventually, I was writing for three newspapers before I moved into television.

BRANT: You were the only foreign anchorwoman in Italy—and one of the best-known journalists, period—on Italian TV. How did you get into television?

JEBREAL: In 2001, after September 11. I started as a regular guest on TV shows because I had experience in the Arab World. In less than a year I was hired by another station. I went to Omnibus on La7 in 2004.

BRANT: Your Omnibus show was a serious one. You interviewed a lot of notable people—including [Italian prime minister Silvio] Berlusconi.

JEBREAL: I’ve interviewed Berlusconi three times.

BRANT: How did you come to write Miral?

JEBREAL: A publisher came to me. They said, “We’d like you to write a book about how an immigrant became an anchorwoman in Italy.” I didn’t want to write about that exactly. If it was about me, then I had to tell the story of Hind, my father, my mother. . . . So I started writing the book that eventually became Miral. My publisher told me in 2003, “If we sell three thousand copies we’ll be very lucky.” It became a bestseller in Italy. It has since been translated in 12 countries including China, Russia, and India.

BRANT: I wanted to talk to you a bit about how you developed Miral as a film with Julian Schnabel. As you know, I’ve seen Julian’s film now several times and I’m a great fan of it. But the reviews I’ve read of it that I have trouble with are the ones that try to impose the larger political aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict onto what is really a coming-of-age story. There is also the other aspect of the project, which is your personal relationship with Julian and how close you’ve become in sharing this journey of making Miral into a film. When did you first meet him?

JEBREAL: 2007. I met Julian before I met him.

BRANT: What do you mean?

JEBREAL: I was having lunch with Walter Veltroni, the mayor of Rome, and he told me, “A man came to my office, he was wearing pajamas and asked me to turn the lights off.” [both laugh] I said, “Sounds crazy!” He said, “No, he is an interesting artist. His name is Schnabel. You should go and see his show at the Palazzo Venezia.” I did. We met. I knew he was a movie director as well as a painter. A screenplay had been written by another writer based on my book. I asked him to look at it. Three weeks later, after reading the script, he asked if he could read my book so I sent him Miral. He said the book seemed more like a script than the script, and he thought it was a movie.

BRANT: Did you work on the script together?

JEBREAL: Yes. He has a very specific way of describing details. There were things that I left out of the book that I didn’t want to deal with. He asked me to revisit those places, those feelings. In fact, I made an addendum to the book that made it more like the film. He helped me build on what I had initially written. Sometimes he was very tough. He wanted to understand everything, how the history of the conflict in the region has affected people. He really wanted to understand where I was coming from.

BRANT: For centuries, political scientists and historians have described the Israeli-Palestinian situation as an almost impossible one. But what I think is great about both the book and the movie is that neither of them are really about Judaism and Islam.

JEBREAL: The book is not an accusation.

BRANT: You know, we don’t look at George Stevens’s The Diary of Anne Frank [1959] as the quintessential historical documentation of World War II. It is, though, a story that humanizes what was a terrible moment in our history, and I think that your book and the movie Miral humanize the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a similar way. Nevertheless, you have people across the spectrum of beliefs, from Zionists to radical Muslims, who are looking at this film through the lens of other issues that are not in the story. Both sides are guilty. But I think that those sorts of critiques are coming at the film from the wrong direction. It’s an artwork.

JEBREAL: I think the film is also a love letter from Julian to his mother.

BRANT: I knew Julian’s mother, Esta. She was a very wonderful woman, very intelligent. She was the head of her chapter of Hadassah and very much involved in Judaism.

JEBREAL: You know, one day, I told Julian, “I’m happy to go to Israel with you. I cannot wait. We both come from there.” “I come from New York City,” he says. I said, “Yes, you come from New York, but you have roots in Israel. You have memories there even before you have been there. This movie is about your love for this country because you care about the destiny of its people.” He had his own daughter, Stella, play the only Jewish girl in the movie, which is his way of representing the way he feels about that character—there’s a love and a connection. The girl’s name is Lisa. She is tolerant, peaceful and open-hearted.

BRANT: The story is in many ways about a kind of love. How did Julian wind up casting Freida Pinto in the film?

JEBREAL: We were in Israel in pre-production already when Freida entered the picture. We had cast everybody except Miral. It was hard. Julian and I had a very specific idea of what we wanted for Miral, and we’d met many girls and couldn’t find what we were looking for.

BRANT: What was it that you were looking for?

JEBREAL: We needed a girl who had innocence and was smart enough to understand the different emotional levels of each scene. We needed someone who understood the character’s metamorphosis, that she’s evolving and becoming more aware both sexually and politically. We needed an actress and we needed someone real.

BRANT: So how did Freida come to you then?

JEBREAL: We had seen Slumdog Millionaire [2008]. When we were casting Freida was in Los Angeles on the press junket for the Oscars. Julian asked the film’s director, Danny Boyle, if he could put her on tape. We sent Freida some scenes and Danny very quickly filmed her reading them and sent it to us. One scene she was talking to her father, Danny played her father on the tape, and the other was the one where he is dying and she tells him that she loves him. We looked at each other and without saying a word we knew that she was our Miral. We had no doubt.

BRANT: Did Freida have a lot of questions for you?

JEBREAL: They were mostly about the culture. She was very careful in asking private details even though I told her everything. At one point, Julian had to leave for New York so Freida stayed in the house with me. We were alone together for almost a week. She would wake up in the morning and we would have breakfast, and I would read the papers and I had the feeling that she was observing me the whole time. But I didn’t feel like she was invading my privacy. I remember one day we were on the terrace and I was looking at the light and I said, “You know, this kind of light you will never see anywhere else except here. You look at the walls of Jerusalem and when you think of how many wars were fought inside of them, there’s a mixture of the saintly and the diabolic that inhabits this place.” Freida started telling me about India and about the problems with Pakistan and Kashmir, and we discovered that there were so many things we had in common. I think she was able to tap into the soul and the psychology of a girl living in a war zone. You can also lose yourself so easily. I don’t know if it was a huge learning process for Freida or if she instinctually knew it, but she was so dedicated to transforming herself into that character. She did it. What is art? She’s like the best artists. They transcend nationality and identity.

BRANT: So how do you like living in New York City now?

JEBREAL: It’s very challenging. [laughs] What I love most about New York is that I can walk in the street and nobody is looking at me as if I’m different. In my country and in Italy, you have to choose sides. I was a famous journalist and I was also an immigrant and ultimately I never stopped feeling like I was a guest. You can come from China, Russia, any place, and you can be a New Yorker. You can say what you want to say here, really express yourself. At the same time, there’s something that scares me. It’s the way media in the United States presents the rest of the world. I feel like people in America are getting a completely different picture of what’s going on in other countries than what is reality. There’s a deformity in the information that the public is receiving. It’s contained in kind of a bubble—and one day this bubble will explode.

BRANT: Would you ever be interested in working on American television?

JEBREAL: Absolutely, yes. I hope there’s a window that opens in American television where the rest of the world is viewed in a less censored light. There is something about the world outside the United States that is not understood here—that seems threatening to Americans. So it’s time to show the American audience what their country’s relationship is to the rest of the world, as well as what’s really going on in America, which I believe can be done in a great way.

Click here to read more about Rula Jebreal.

Peter M. Brant is the chairman of Brant Publications.