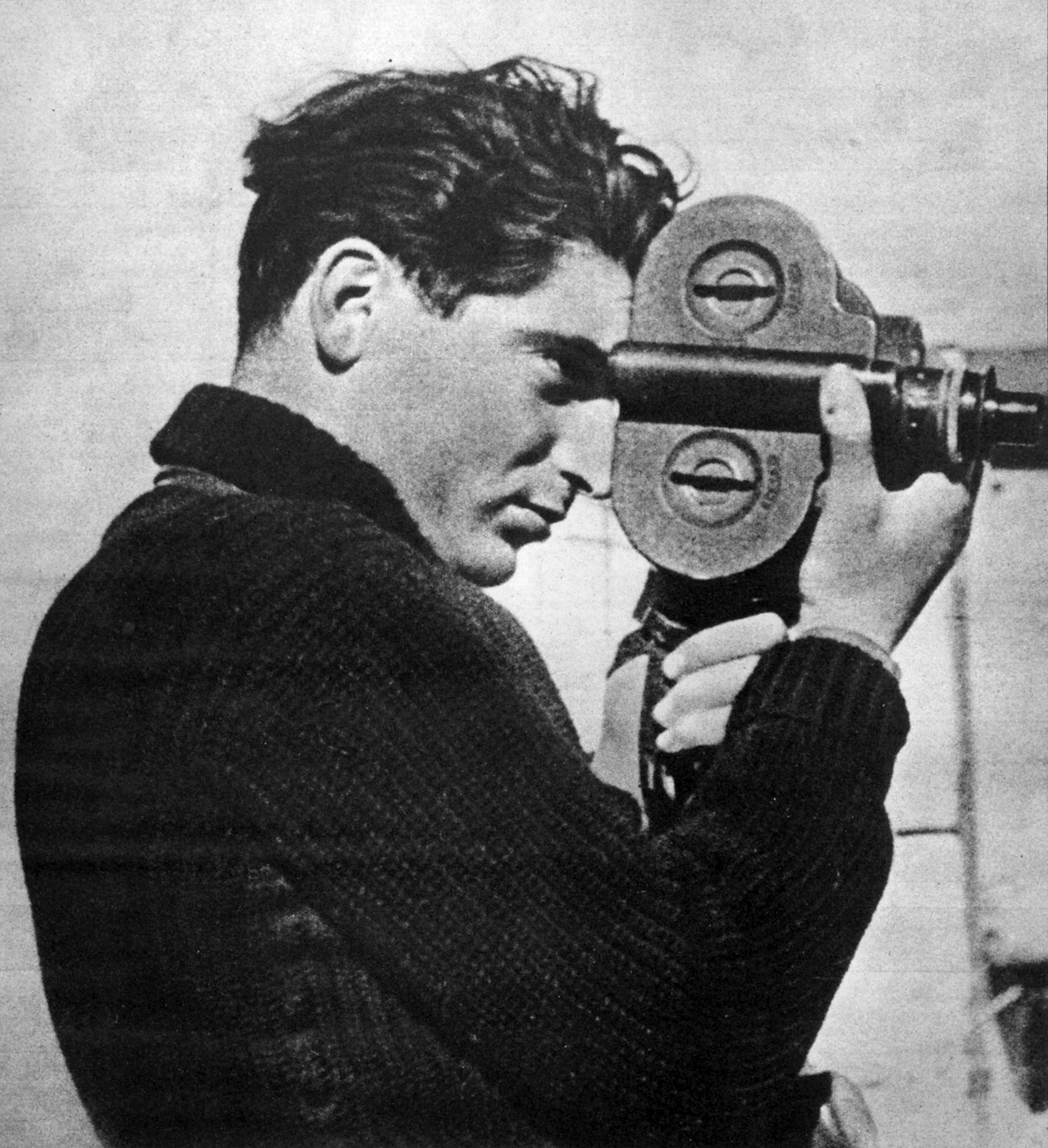

Richard Whelan on the imagined escapades of photojournalist Robert Capa

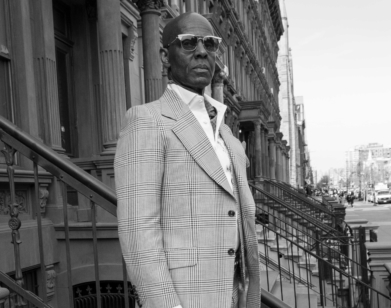

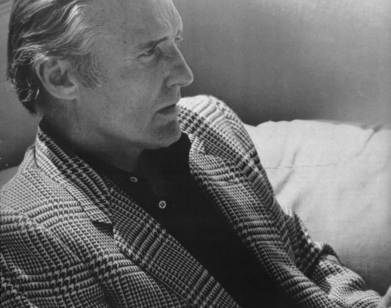

The recent barrage of interest in the real and imagined escapades of photojournalist Robert Capa is in large part due to the publication of two new books on his life: “Robert Capa: A Biography” by Richard Whelan, and “Robert Capa: Photographs,” edited by Whelan and Cornell Capa. Concurrently with these publications, the International Center of Photography opened an exhibition of Robert Capa’s photographs that will tour the country over the next two years. Whelan, who studied art history at Yale, has written extensively on photography for such magazines as ARTnews, Camera Arts and Portfolio. His other books include “Double Take: A Comparative Look at Photographs.”

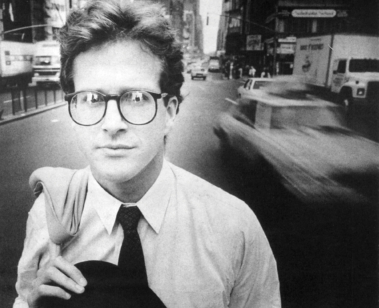

JONATHAN BECKER: What question did you ask yourself most about Robert Capa?

RICHARD WHELAN: I think it was not really any single question; it was more a sense of wanting, as any biographer must, to at least experience vicariously a life completely unlike my own; to have, through Capa, a sense of experience that I will never have directly.

JB: How did you first interest yourself in Capa? Your biography evokes Capa’s charismatic personality.

RW: As I found myself becoming more and more interested in political history and photojournalism, I was naturally drawn to Capa’s work. I met Cornell Capa on an assignment. I was doing a story about him and the ICP, but a great deal about his brother came out in the course of the conversation. I did an interview with Andre Kertesz, both of whom were very close to Robert Capa and spoke very warmly of him. So I became intrigued by the man and soon realized that he was really very little known, surrounded with myths and legends and misconceptions, and I thought that I would like to take on the biography.

JB: What did Cartier-Bresson have to say about Capa that was intriguing?

RW: Well, my favorite thing that he said—about the man, as opposed to his work—was that Capa was the truest anarchist that he had ever met. He treated everybody exactly the same, whether it was Queen Juliana of the Netherlands or a chambermaid at the Hotel Lancaster in Paris, where he lived most of the time.

JB: And how did he treat everybody?

RW: He had a really exceptional ability to be comfortable with anybody, to make anybody comfortable with him. He had a genuine liking for people, and, in fact, at one point a Camera magazine writer asked him whether he had any advice to pass on to amateurs, and he said, “Yes, tell them to like people and let them know it.” That was really his own credo. I think that comes across very clearly in his work.

JB: Charm.

RW: Yes, and his ability to put people at ease. He was not a photographer who stood aloof from his subjects and tried to catch them off guard. On the contrary, in many of his pictures there’s a sense of real rapport. He often spent time with his subjects. He’d go out drinking with them, get to know them and only then would he photograph them.

JB: What other stories led you into this, the seductive life of Robert Capa?

RW: Well, I read his own World War II memoirs, Slightly Out of Focus, which is marvelously entertaining. He actually wrote it with the intention or hope of selling it to the movies.

JB: In a way his own life is that of a performance.

RW: Well, on one level, yes.

JB: But he went on to enhance it.

RW: It’s true that he hated to be bored and loved to tell stories, loved to make people laugh with accounts of his misadventures, and there really were two people. There was Endre Friedmann, his inner self, to whom he was always true. There was a self that responded very directly to people in a very honest, unaffected way. Yet there was also this fantasy character, this alter ego, the invented Robert Capa.

JB: When did you first become aware of this invention?

RW: John Hersey wrote a story, a review, actually, of Capa’s war memoirs, entitled “The Man Who Invited Himself.” Capa and Hersey were friends during the war; they met in Sicily. Capa told him a lot of stories about his early life in Berlin and Paris in the ‘30s, and it was in that piece that Capa talks about having invented himself. He made up his own name, made up a persona and then, taking on the role for himself,

really became Robert Capa, the man he had invented.

JB: What was his most outrageous fabrication or story?

RW: The most outrageous was the notion of inventing somebody, an imaginary character, and then becoming that person.

JB: How was Endre Friedmann really true to himself?

RW: Endre Friedmann, as a teenager in Budapest, was a very politically active, politically committed, leftist kid, and that political commitment never left the man. But the character of Robert Capa was in some ways, in fact in most ways, the opposite of Endre Friedmann. He was glamorous, debonair, consorting with millionaires and movie stars, drinking champagne, living the good life.

JB: Were there any causes that he pursued later in life?

RW: He was very active in a very informal group that protested McCarthyism, and the blacklisting in Hollywood. Capa was in a precarious position as a new citizen of the United States. He came a citizen in ’46, and because travel was so important in his work, he was terrified of losing his passport. So he was cautious in his activity, but he certainly was very committed to fighting McCarthyism.

JB: Was he involved in Hollywood?

RW: He met with Ingrid Bergman in Paris in 1945, and followed her to Berlin, where she went to do a USO tour. Once the war was over, he followed her to Hollywood and toyed with the idea of having a career out there, got a job as an associate producer, director and writer, but Hollywood just wasn’t the place for him. He knew a lot of people in the movies, had a lot of friends who were directors and actors, but professional his involvement was pretty…

JB: But he loved the ambiance.

RW: He didn’t love the ambiance; he loved a lot of the people, individually. But actually, he hated Hollywood, he hated California. He felt bored and restless, and he’d drink too much. He complained that California was a bad place to have a hangover because the sunlight was so bright.

JB: And how long did this go on with Ingrid Bergman?

RW: It went on altogether for about two years. She was still married to Petter Lindstorm, and she writes in her memoirs they’d been having a lot of trouble. She makes it quite clear she was prepared to marry Capa, but he told her he wasn’t the marrying kind, that he really felt he couldn’t be pinned down. If an assignment date or an assignment came up, he wanted to feel free to take it. She felt that she really couldn’t continue the relationship on those terms, so they broke off in ’47.

JB: Then two years later she ran off with Roberto Rossellini.

RW: Yeah, I think Capa had really planted the seeds of change. He had talked to her a lot; he told her that she had to change her life, that the way she was living was ridiculous; she was working too hard. She didn’t seem to have been able to take his advice right away, but it certainly registered. It’s an interesting side point that Capa was one of the people who suggested that she go see Open City, the film that convinced her that she simply had to work with Rossellini and led to her meeting with him.

JB: So Capa followed Ingrid Bergman to Hollywood, where she was living still with her husband?

RW: She was, but Capa managed to see relatively little of her. He spent a good deal of time on the set of Notorious, which she was making with Hitchcock in the spring of ’46, and then that summer when she was working on Arch of Triumph, he shot stills for Life and other magazines. It was difficult for them to spend much time at all together. Irwin Shaw tells that they had some trysts out at his house on the beach in Malibu—but aside from that, they had very little time alone together. They also managed to spend time in New York while Ingrid was on vacation, and that was really probably the best time that they had together.

JB: What else did he do in his six months in Hollywood?

RW: Well, he was supposed to spend time in the screening rooms, watching classic films, and watching in the cutting rooms and learning the technique of making films, watching on the sets and so on. The whole business just bored him terribly, and Charles Collingwood, who was out in Hollywood at the same time, remembers they spent most afternoons out at the track. They had long lunches at Mike Romanoff’s and spent a lot of time at friends’ houses, dinner parties, everything except work. But he was always fascinated by the movies. In 1941, when Hemingway sold the film rights to For Whom the Bell Tolls, he thought that Capa would be the perfect person to play Rafael, the gypsy, and Capa loved the idea. It just didn’t work out. Somebody else was cast.

JB: How did he know Hemingway?

RW: He met Hemingway in Madrid during the Civil war. They quickly became good friends.

JB: He took some of his great pictures during the Spanish Civil War.

RW: He certainly did. He was really one of the first photographers to take the 35-millimeter camera, which was so easily maneuverable, right up to the front line of action. The camera simply hadn’t been available in previous wars; no war had been covered that way. So the photographs he brought back created a sensation.

JB: What made Capa so suitable to be a war photographer?

RW: A number of things. He loved adventure. He had always tried to make his life as exciting as possible, and he could certainly find all the excitement at the front that he wanted. Beyond that, he was a gambler by temperament; the danger of the front attracted him. And I think most importantly, he had a tremendous personal stake in the war, in the Spanish Civil War to begin with, as the first war against fascism. It

was a war in which he had a real commitment. He felt passionately supportive of it—and so it was this culmination of political commitment, passion, bravery, intense sympathy for the people he saw at the front, as well as a great level of camaraderie that he found. As a homeless, more or less refugee, the intense friendships that he formed at the front meant a tremendous amount to him. There was a great deal that suited him temperamentally to be a war photographer.

JB: You seem very confident of your own perception of his personality.

RW: Well, I interviewed about 150 people who knew Capa. So much of the biography, many of the personal insights, are based very directly on the memories of people who knew him well. I read everything I could find about him. And also a very strong sense of the man comes across from his photographs.

JB: And your being such close friends with Cornell Capa must have enhanced your sense of Capa’s personality.

RW: Absolutely. Cornell naturally remembers his brother vividly and was very generous in sharing his memories, his insights. He also has the archive of his brother’s papers, all his letters, all the vintage prints of his photographs, contact sheets, caption sheets, and so Cornell’s cooperation was essential.

JB: Was it Cornell Capa who helped you discern some of the fabricated parts of his life from the real parts? How did that come about?

RW: A lot of that came about, really, from checking the verbal accounts that I got from people against Capa’s own caption sheets, where he noted down the heard facts that sometimes later got elaborated in the re-telling into slightly altered stories. I spent a lot of time doing research with regimental histories of the units that Capa was with and discovered the actual circumstances in which many of the photographs were taken.

JB: Was Cornell Capa himself surprised to find some of the discrepancies?

RW: Yes, I think he was quite surprised. He has said that for him, the joy of my having done this book is that he’s learned a great deal about his brother.

JB: What was his relationship with the woman [Gerda Taro] with whom he conjured up the name Capa?

RW: At first, actually, before they became lovers, she became his manager, more or less, and this relationship maintained some of that, and so she was involved in the whole conception of Robert Capa. She was working as a photo agent in Paris at the time, and so it was she who worked to build up the reputation of this imaginary photographer called Robert Capa.

JB: What did they do in Paris together?

RW: Cornell had gone to Paris with the hope of studying medicine; that didn’t work out, so Capa arranged for Cornell to be apprenticed to a Hungarian photographer.

JB: Who?

RW: His name was Emeric Feher, otherwise not really known at this point. Capa and Cornell set up a darkroom in the bathroom across the hall in the hotel where Cornell was living, and Robert Capa would send his film back from Spain—by that point, he was beginning to cover the Spanish Civil War. Cornell would develop the film, print it in the bathroom, and then take the wet prints to his job, where they had an electric print dryer. His pay consisted entirely of the right to use this print dryer. He was finally fired for using too much electricity.

JB: He was a devoted brother.

RW: They were devoted to each other, yes. Bob Capa did everything he could to encourage Cornell, to inspire him, and Cornell, for his part, was very proficient technically very early on. He helped his brother to master the art of flash, for instance. Then Cornell came to New York before Bob Capa. Also Cornell spoke English, so he adapted much more easily to America. When Bob Capa came to the United States at the outbreak of World War II, Cornell was very much his guide to American customs, his intermediary in his dealings with Life magazine and agents and explained to him the ins and outs of the American photographic scene.

JB: What was of interest to Capa in New York?

RW: He was fascinated by American culture and approached it almost as something of an anthropologist. American culture was so alien to him, he found it terribly amusing, but he never really felt at home here. He was a European at heart, and in particular he really was a Parisian. Paris was his spiritual home.

JB: Who were Capa’s direct influences?

RW: His earliest influences were from the school of Hungarian socially concerned photography, which had in turn been greatly influenced by Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, the two great reformer photographers in the United States. When Capa arrived in Berlin, he soon found a job at the Dephot agency, which was the leading agency representing photojournalists. The agency was headed by Simon Guttman, who was one of the great formers of the tradition of modern photojournalism in Germany. Capa worked at first in the darkroom of the agency. When he moved to Paris in ’33, he soon met David Szymin, later David Seymour, who worked under the name Chim; he met Henri Carier-Bresson, and most importantly, he met Andre Kertesz, who was a great influence on Capa.

JB: Friendships were formed among certain photographers in Paris at this time that actually led to the foundation of Magnum.

RW: He became very close to Cartier-Bresson and Chim, and the friendship lasted. After the war, the three of them, along with two other photographers—George Rodger, an Englishman, and Bill Vandivert—formed Magnum.

JB: And later on, how did Magnum figure in his career?

RW: Magnum had been founded as a photographer’s cooperative agency, as a convenience, really, for the photographers—a central agency to arrange assignments and have work developed, sell the work to magazines. And Capa, who was a very wonderful businessman, very enterprising, got along fabulously with editors and had a lot of ideas for others. He found himself drawn more and more to Magnum as a businessman. In fact, rather than being a support to his career, Magnum really became pretty much of a burden for him. He found himself doing less and less photography and more and more business. By 1952, he was becoming pretty sick of that. He was bored with the kind of assignments he was doing—he’d been doing a lot of movie publicity stills, a lot of travel pieces for Holiday magazine, which he had enjoyed, but it wasn’t really what he did well. He was getting restless. During 1953, he had a year of crisis; he had a terrible ordeal with his back, and the United States State Department revoked his passport for several months…all of this provoked a general crisis, a re-evaulation of where he had been recently and where he was going. He began to feel that he wanted to get back to war photography, which was what he really did well. So in the spring of 1954, when he was in Japan and Life needed a replacement of their photographer stationed in Indochina, they contacted Capa and asked him whether he would take the job for 30 days. He accepted immediately; it was just the sort of thing he had been looking for.

JB: And, of course, it led to his end.

RW: Yes, in Indochina during a fairly routine French operation to evacuate several small forts that could no longer be defended against the Viet Minh guerrillas, Capa walked out in a rice paddy beside a convoy that was stalled by sniper fire and stepped on a landmine.