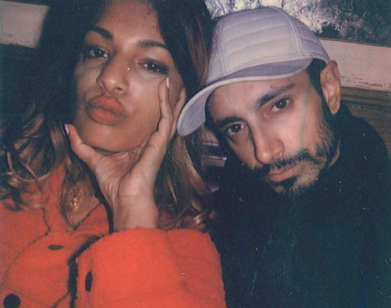

Riz Ahmed talks The Simpsons’ race problem with comedian Hari Kondabolu

Hari Kondabolu is tired of explaining racism to (white) people. The Queens-born comedian would probably rather discuss anything else, but stays focused on the issue purely out of necessity. “Telling me that I’m obsessed with talking about racism in America,” he explains, “is like telling me that I’m obsessed with swimming when I’m drowning.” You can hear the exasperation in his voice.

Before becoming a full-time standup, Kondabolu earned a Masters in Human Rights from the London School of Economics and cut his teeth as a community organizer. He’s often dubbed a “political comedian,” but the term belies his serious dedication to activism. Kondabolu has produced three incisive albums that dive deep into America’s racial psychology: Waiting for 2042 (2014), Mainstream American Comic (2016), and Hari Kondabolu’s New Material Night (2017).

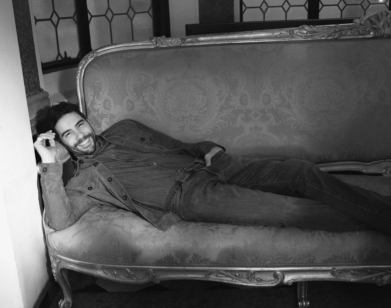

This year, however, Kondabolu is taking on Apu Nahasapeemapetilon—the Indian convenience store owner from The Simpsons. In his new documentary airing November 19, The Problem With Apu, Kondabolu explores modern minstrelsy and the history of South Asian media representation. Discussing the issue with The Night Of and Swet Shop Boys’ Riz Ahmed, he reminds us that even satirical cartoons play a role in a tangled history of power.

KONDABOLU: How strange is it, Riz, that we’re two brown men who have agreed to have a phone call where white people are listening silently, and writing down what we’re saying? And we agreed to this!

AHMED: It’s not that different to every day, right?

KONDABOLU: [laughs] If Interview wants a transcript of what we said, if they’re not sure, they can just ask the government and they’ll get it.

AHMED: If you read the small print on any of our messenger services, it’s pretty much the same thing. But it’s cool, at least this way it’s all out in the open. I want to know how you get past this as a standup [comedian] because, in a way, I think it’s the most extreme version of this. As a performer, you are seeking the validation of others, and as a standup comic, it’s binary, almost. Either people laugh, or they don’t laugh. So how do you write good material without being conscious of trying to “chase the laugh”?

KONDABOLU: It’s a sick thing, right: people are afraid of public speaking. I do public speaking, except my public speaking involves the audience only having one type of emotion and one type of reaction. If they have anything other than laughter, it’s a failure. That’s an absurd thing for a human to try to seek. The main thing to realize is that whatever I say, it’s my truth and I believe in it, and if I don’t get a laugh off that, then it’s not working.

So I center myself knowing the two things I need to focus on are “is this something I believe and can stand by,” and, “Is it making people laugh. And the people who are laughing: are they laughing the way I want them to laugh? Are they laughing at me or are they laughing with me?”

AHMED: It’s like what Dave Chappelle did.

KONDABOLU: Yeah, totally. Is it a weapon? The only difference with the Chappelle thing is that I think about it in intersectional terms, right? So it’s not just a matter of “Are they laughing at me?” But am I kicking downwards? In order to make a point about race, am I saying something insulting about women? I don’t want it to be at a cost to anyone else, and that’s difficult because I’ve narrowed the amount of things I can say to some degree. It makes my voice clear—people know my ethos—but at the same time, it narrows the playing field. I can only use this much space. But I think actually, for me, that makes it more exciting and interesting: it’s an additional challenge.

AHMED: I think that the U.S. has a slightly more advanced—or at least a more complicated—conversation around who’s fair game. In terms of “What direction can you kick in?” It seems to me the consensus is about where you sit in the power gradient. If you’re part of a relatively privileged community, then don’t get up there and start telling jokes or stories or satirizing marginalized communities that may not have access to the same stage or microphone that you have.

KONDABOLU: Exactly, exactly.

AHMED: Or carry a historical burden of being denigrated. In that context, you are not speaking truth to power; you’re compounding the worst effects of an unfair power structure. People seem to understand that a bit more in the States, whereas, over here [in the U.K.], it’s kind of an undeveloped conversation. So a famous standup comedian recently had a Halloween party dressed as Kim Jong-Il. He’s a white dude, he painted his face yellow. He put prosthetics on his eyes to make them narrower. Some people said, “Hang on a minute—you can’t do that.” And a large amount of people said, “Wait, why not? Does that mean I can’t dress up as Donald Trump and paint myself orange?” It’s really tricky to not have a way to talk with people and explain to them “it’s not like no one can dress up as anyone.” It doesn’t mean that Hari can’t get up and tell a joke about a relatively privileged community like middle-class white dudes. He can, because in that context, he’s kicking against power.

KONDABOLU: Also, who controls the images? Ultimately, we don’t control the images. This is the minimum we’re allowed to ask for: we don’t get to control most of the media. We fight to have some say in the ways we’re represented. At the bare minimum, don’t insult us in person. That’s all we ask! [laughs] Let us at least be able to function freely in the world.

AHMED: In terms of your documentary, is the dream to get to a point where there’re so many different portrayals of people of color, and they’re so frequently depicted as being as intelligent or as heroic and on equal footing with white characters that you can, quite happily, have an Apu character? And Apu stops being an archetypal, “Hey, isn’t this what all South-Asians are like?” and starts just being like, “Oh, yeah, this is just a funny dude who works at the store.” Is that a dream?

KONDABOLU: I think it’s even more specific than that. You don’t have immigrant characters with a great deal of depth, generally, especially if they’re South-Asian. I don’t see many characters where you get a sense of the immigrant experience: where you get an experience of hardship, and an experience of humor. One that’s derived not from mockery, but actual [precedent]. You don’t see that with immigrant character portrayals, and it’s not only South-Asians. When they made that character, Apu, it’s not about us; it’s about our families, man. About that generation. So to me, it’s about having a fuller voice. When I made this film, it wasn’t even about Apu. That’s the trigger: that’s the thing that many of us had growing up that would be the immediate example, and it’s The Simpsons, so everybody understands that; it’s under everyone’s nose. But to me, this is part of a larger legacy of minstrelsy, and I think it connects to the idea of like, “Why is it wrong to wear this Kim Jong-Il character?” Well, why is it wrong for a white guy to do a funny voice? It’s not our story! You’re representing our faces, our features, our stories, our voices, our families, and you’re doing it wrong! That’s what it’s about.

AHMED: But there are two different points you’re making there. One is, “Is it your story to tell?” And then the second point you’re making is, “You’re doing it wrong.” So if someone goes and does their research, puts all their time and energy into depicting things with nuance, and doing it accurately, then is it cool? Or is it still a problem of it being not your story to tell? Because if that is the case, then are the only screenplays you can write about brown people, and the only screenplays Aaron Sorkin can write are about white people? Is that a kind of creative ghettoization?

KONDABOLU: I don’t think it’s that, because it goes back to power. It’s not equal footing, so it’s not saying, “You can only write this and you can only write that.” Our stories haven’t been told by us historically, right? Like you can only write stories about your experience. When you’re a person of color in white America, you know white people. You know why you know white people? Because you can’t enjoy any kind of entertainment if you are not able to humanize white people. If you watch a film and are like, “Oh, this has white people in it? Then I’m not interested,” then you can’t enjoy anything in America!

As a person of color, you are forced to humanize white people: you’re forced to understand their lives, their stories, their complications, their culture. You have to! Not only for survival, but also to just enjoy anything. Meanwhile, if there’s a person of color in a movie, and it was originally thought to be a white character and it’s now a person of color, everyone flips out. “This isn’t supposed to be a person of color!” “I can’t relate to this!” “This is a black movie because there are black actors!” Meanwhile, we don’t call these “white movies” because we have to humanize them. We have to humanize white people. That’s why I think it’s different. We can tell our authentic stories, because we know our stories. And we know your stories, because we grew up reading your stories. We have seen your stories. You’re the majority: we know you. That’s different, man. There’s a big difference when you’re talking about cultural things, where we have a double lens and we can do both.

AHMED: When you get this kind of pushback, against arguments to do with cultural appropriation, and people say, “Well, you’re just kind of a creative segregationist,” what that argument is totally blind to is historical context. Historically, certain people and certain voices have been silenced: certain stories have been marginalized. I think it’s about access: certain people haven’t had the mic. If we live in a world where there is an equal chance of your show getting green-lit or your wife-counterpart getting a show green-lit, or a woman of color, or a trans artist getting their story told, and it being celebrated, then cool! You go write a Korean story. I’ll go write a Jewish story. Woody Allen can write about being a Sikh guy. Cool. But the reality is that we don’t all have equal access to the tools of storytelling, and the platform of storytelling.

I think being mindful of who has the opportunity to tell these stories is a big part of the conversation. If it was a level playing field societally, but also historically and in terms of who has access to tell stories, then it would be a different conversation. Given that it isn’t, I get [people’s] sensitivities. And, in a way, I don’t even think they’re sensitivities. They’re corrections. We need to kind of make some systemic corrections, you know?

KONDABOLU: Definitely historical corrections. How about this? Give 50 years where only people of color are allowed to make film, TV, and art.

AHMED: [laughs]

KONDABOLU: Just give us 50 years where we’re the only ones who are allowed to profit from art, and then you can do whoever you want. In fact, I’ll buy you the paint. Whatever you want. Just give us 50 years. 50 years. That’s it.

AHMED: Okay! That’s not a bad deal, man!

KONDABOLU: No, I think it’s a reasonable deal! Because think about it, after the 50 years are done, you have all these white people talking about how awful those 50 years were. They’ll make tons of Oscar-winning films about those 50 years and the depression of art. Then they’ll make a ton of money afterwards! Think of it, it’s like our story. Like this Apu thing, man, for me, I’m happy I made this film, but it’s so corny, because we’ve been talking about this for 30 years!

AHMED: Yeah, you don’t want to have to be doing this.

KONDABOLU: Yeah, there are so many other things I want to talk about, but I’m telling people because they’ve never thought about it. I wouldn’t mind naming the film “I have to explain this to you?!” Like, this seems so obvious. You have to tell your stories because they didn’t let us tell it before!

AHMED: There’s a sense of catch-up.

KONDABOLU: Exactly. It’s a historic correction. Like, let’s fill in that gap now. To a lot of people, this is old! We’ve discussed a lot of this stuff already. Now, this is more for everyone else to get to.

AHMED: I can totally understand your point. I can relate to the sense of like, “Man, I don’t want to have to be talking about this stuff!” With political art, in a way, you’re campaigning or lobbying for your own irrelevance. You’re trying to get to a point where the points you’re making are passé and people are already clued up on that, and it’s not opening anyone’s eyes anymore, and it isn’t a conversation that needs to be had. I feel similar to that when I give talks or sometimes in my music, I’m like, “Man, there are other things I’d also like to be talking about. Not only something that’s important to me and that I have no choice but to be interested in.” At a certain point, you feel straitjacketed into the burden of representing, and throwing up a fist because someone has to.

THE PROBLEM WITH APU PREMIERES NOVEMBER 19, 2017 ON TRUTV.