O De Richard Schechner

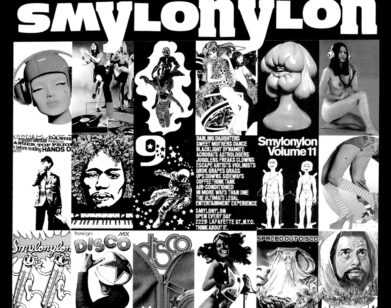

ABOVE: A SCENE FROM RICHARD SCHECHNER’S IMAGINING O.

As a key figure of the avant-garde and experimental performance art movement in the later half of the 20th century, director and writer Richard Schechner’s works quickly became synonymous with the inherently daring, the sexual, and the collaborative. He founded the legendary SoHo-based Performance Group in 1967—which was arguably to experimental theater as Monty Python was to comedy—that pioneered progressive (and very erotic) productions that altered preconceived and traditional notions of space, movement, and interaction. Steadily working in the years since, he was also one of the founders of the performance studies department at Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, considered one of the best training grounds in the country for aspiring performance artists.

His newest work, Imagining O, brings him out of the five boroughs and into New Jersey as part of the Peak Performance series at Montclair State University. Based on Ophelia in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the protagonist, O, in Anne Desclos’ erotic French novel Story of O, Schechner created and re-envisioned an original and experimental play that again goes beyond the “normal” constraints of a stage. Without giving too much away, the entire performance venue is, quite literally, a platform that beckons—and requires—intimate performer and audience interaction. Nowhere is safe, not even the lobbies or hallways, from the sexuality and artistry of the performers.

Interview called up the busy octogenarian last week for a quick chat while he was in the midst of final rehearsals.

DEVON IVIE: How are the rehearsals going?

RICHARD SCHECHNER: Do you know anything about farms? When you cut off the chicken’s head and it still runs around for awhile? Well, that’s me. [both laugh]

IVIE: What inspired you to combine characters from works by Shakespeare and Desclos? How was this conceived?

SCHECHNER: I’ve long been very devoted, interested in, and obsessed with the probing of Hamlet and I’ve done three productions, if this one counts, in a variety of ways: “African American” Hamlet and “gay” Hamlet. And as I kept working on Hamlet, I realized that Ophelia is an extraordinarily important character who isn’t really given the chance to give her own voice, or not much of it. I wondered what would Ophelia look like if there were no men responding to her, and if it was only her voice? So I stripped her lines out of the play and made an Ophelia monologue. I saw that monologue with her being very polite to Hamlet and obedient to her father, brother, and the king—she was a strong young woman but kind of “owned” by these men around her and not treated well.

At the same time, I thought about Pauline Réage’s [the pseudonym Desclos used while writing Story of O] or Desclos’ novel, and I happened to come upon this interview with her in The New Yorker where she explained who she was, why she wrote it and what it’s about, and it struck me that there was a similarity between the characters of O and Ophelia. There was that convergence. Ophelia is not very erotic, but O is, and it’s a very articulate and a very beautiful novel. At the end, she’s “given permission” to commit suicide, and even at that moment she doesn’t have total agency—she asked Sir Stephen if she could commit suicide.

And there was an irony in the word “O,” eau, which in French means water. The character O is eau and Ophelia drowns in a lot of eau. So this struck me also. I decided to play with these things and make a performance in which these varieties of women were “suffocated” to some degree, were exploited, and came together at a level to explore the ramifications of these things. And then the opportunity arose to do a workshop investigation of these themes at the University of Kent [in Canterbury, U.K.], so I decided to do that. It was out of that workshop that I made this text and then collaborated with [co-director] Benjamin Mosse. We explored these themes and found them to be very fruitful.

IVIE: Imagining O is part theater, part dance, part installation art, and also incredibly interactive with the audience.

SCHECHNER: And site-specific. It includes all of those things—there are several scenes where the audience’s job is simply to watch and listen. And the audience is a group and the performance is a group. And for other scenes there’s a lot of one on one, with one spectator and one performer. That’s quite unusual in the theater.

IVIE: Did you find it difficult to seamlessly incorporate all of those elements into one show?

SCHECHNER: [laughs] Everything is difficult, and who knows how successful we’ll be. But we’re trying. It’s like ordinary family life—sometimes you’re alone, sometimes you’re with one other person. I wanted to break through that barrier and allow for a wide spectrum of participatory spectator and performer interactions.

IVIE: What do you hope viewers will take away from this performance?

SCHECHNER: That’s the kind of question that’s in a sense not proper for me to answer. I would say an experience that moves them, an experience that stimulates them to think, and experience that helps confront their own imaginings. I wanted to further stimulate that distance. Also, the simple matter, I want the audience to come away that they had a good time. Even if that good time was not always pleasant. Sometimes you can have a good time that’s not pleasant—it’s not like Disneyland, I’m not asking for that. And something that they can think about.

IVIE: What traits do you think a potential performance artist needs to possess in order to succeed?

SCHECHNER: If we really knew that, there would be nobody new arriving on the scene because people would only learn what their teachers teach and wouldn’t really advance. Looking back at the history of art, like abstract expressionism or conceptual art, each group of pioneers were not “successfully educated” and rejected their education and had other ideas—they didn’t even knew what these ideas were at a certain point. I think a great education is one that stimulates a student to do his or her own work.

IVIE: What would you say is the biggest misconception of performance studies and performance art?

SCHECHNER: Hm. What would you say?

IVIE: I feel sometimes that when people hear something is “performance art,” they automatically assume it’s going to be quirky or odd, which is an unfair assumption.

SCHECHNER: I would agree with that. I think that people sometimes confuse the innovative with the strange, the weird, or the unfamiliar. Things can be unfamiliar and that can be quite good. At the same time, there is bound to be more failure than success. When you go beyond the “boundaries,” you’re sometimes going to fall off the edge. You can’t expect that experimental performances or performance artists will have the same number of hits in the Broadway sense. You have a taste: you want to go see something that may be new and that may fail, or you want to see something that’s tried and true but familiar to you and kind of boring. It’s like a seesaw—you can have high excellence but not much innovation or have high innovative and sometimes fail.

IMAGINING O RUNS TONIGHT THROUGH SEPTEMBER 13. FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT PEAK PERFORMANCES’ WEBSITE.