Richard Prince

I went out to California right after high school, and that’s when I first did acid, right on Sunset Strip. I was a completely clueless teenager. Drop out, tune in, turn on.Richard Prince

In the spirit of full disclosure, yes, I am good friends with Richard Prince, and, no, he never gave me more than four strokes a side. Actually we became friends quickly because in the ’80s there weren’t too many congenial bohemians a guy could play a round of golf with. We belonged to the same club once, Hampton Hills, on Long Island, and I remember the day we were on the first green putting when a guy came zooming up to us in a golf cart and said that Richard couldn’t play in the black, paint-splattered jeans he was wearing. Richard offered to take them off, but that wasn’t legal either, so he went all the way back to the clubhouse, bought a pair of shorts, put them on, came back to the green on the long par four, and sank the putt for a birdie. Years later we were sitting by Richard’s pool in Bridgehampton, New York, watching a huge plume of smoke rise from the Central Pine Barrens, where thousands of acres were aflame, and we both said at once: “I hope Hampton Hills is on fire.”

Today Mr. Prince plays at the Bridge in Bridgehampton, where he has curated the great contemporary art collection in the clubhouse. Until recently, he was club champion. I remember we were walking up a fairway there when he told me a secret: that he was collaborating with Marc Jacobs. “If this works,” he said, “I can retire.” That’s one of his jokes that won’t wind up on a painting. Some people, like him, could never retire. Sometimes I sense he thinks that the art is getting in the way of the golf and the beach, but, hey, a guy has to make a living. He’s making a living, all right. In the last decade the world has discovered what his foursome knew all along: In golf, he’s good; in art, he’s a grand master. For a while he held the record for the highest amount ever paid for a photograph-for his photograph; he wasn’t the buyer. I have to point that out because, among other things, Richard Prince is a fierce collector. If you said that he has elevated collecting to an art form, you would be accurate. You can see it in the galleries, in his plinths of stacked first editions arranged to create a certain esoteric resonance. If you know him you may have seen it in his extraordinary personal library, the building where much of his collection of books, manuscripts, art, and ephemera is housed. Like Andy Warhol, Richard Prince loves art so much he not only makes it, he buys it too. I interviewed Richard at Gagosian Gallery in downtown New York, where he showed me his new Rasta paintings. (With his Massachusetts accent, Rasta ends in r.) Richard said it was the first time he’d set foot in the gallery. Was he kidding? You got me. Sometimes you don’t know. While we were talking, his friend Leonardo DiCaprio showed up and also got his two cents in here along with a sandwich.

GLENN O’BRIEN: So what have you been collecting?

RICHARD PRINCE: Well, I’m still collecting books. John McWhinnie tracked down Carolyn Cassady—she’s living in England-so we got a whole bunch of what was on her shelf. I got Neal Cassady’s copy of On the Road, which is pretty exciting.

GO: Is it dedicated?

RP: No, I think it’s just the copy that Jack [Kerouac] gave him. Cassady wrote his name in it and read it cover to cover and made some marginal notes. But it’s getting to the point where I need to almost separate myself from the book collection because it’s becoming too much of a responsibility. I just got hold of Neal Cassady’s original manuscript for The First Third. He wrote it in ’53, and then he corrected it for, like, 10 years. I also just acquired Kerouac’s original typed scroll for Big Sur. Everybody knew that he did scrolls for On the Road and The Dharma Bums, but nobody knew that he did it with Big Sur.

GO: Big Sur might be the most depressing book I’ve ever read.

RP: Well, the scroll was twice as depressing because it’s twice as long. It might even be three times as long as the finished book—they edited it completely. What they ultimately published is about one third of the scroll.

GO: Did Kerouac’s estate just have that? Or where was it?

RP: It came from the Sampas estate [which controls Kerouac’s estate]. John McWhinnie and Glenn Horowitz [of John McWhinnie @ Glenn Horowitz Bookseller and Art Gallery in New York] are very good at locating things. They got me one of the draft manuscripts of The Road by Cormac McCarthy. It was the same thing with Hunter S. Thompson-they got me his manuscript for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I’ve also got a lot of Timothy Leary stuff. I’ve become very interested in Timothy Leary recently. I didn’t realize he escaped from jail. So I have Leary’s original little map that he made of how he escaped and where he went.

GO: Wasn’t Leary in the same jail as Charles Manson for a stretch? They were, like, neighbors on the cellblock.

RP: Leary was jailed, escaped, traveled across America and went to Europe, was eventually caught, and put back in jail, for a time in the same one as Manson.

GO: I interviewed Timothy Leary once in his house in Beverly Hills.

RP: Before he died? I mean, obviously, but . . .

GO: Yeah, I interviewed him before he died. [Prince laughs] It was actually a few years before he died. He seemed to be . . . drinking a lot. He was really a hustler. A networker. It was funny because he reminded me of Jerry Rubin. I met Jerry Rubin [Yippie and Chicago 7 defendant], too, after he went from being the ultimate hipster, a very underground person, to being like, [enthusiastic] “Hi, I’m Jerry Rubin!” He was then totally into networking and throwing yuppie mixers at Studio 54. He’d become a total suit and tie. Leary seemed like he was sort of going in that direction—marketing.

RP: It’s interesting how people who were once fairly radical can become, later in life, kind of conservative and not just in terms of politics—how if you’re an artist, you can start out being somewhat avant-garde and then end up doing landscapes. Sometimes the opposite can happen, but it’s usually the other way around. I mean, look what happened with Kerouac. You know, he really became kind of a Republican.

GO: Some people say he was always sort of a Republican. He was a mama’s boy.

RP: Well, some of the best artists—I mean, [Paul] Cézanne and [Giorgio] de Chirico come to mind—basically lived with their mothers.

GO: Andy [Warhol], too. But with Kerouac, I don’t know. A lot of people who took amphetamines became half brain-dead.

RP: But I think that people underestimated how intelligent Kerouac was and how well-read he was, and I think that really got to him. It’s somewhat like what happened to Jackson Pollock, too, where what he did became part of some comedian’s act—you know, how they started calling him Jack the Dripper. The term beatnik came out of what Kerouac referred to as beat, and then it became kind of like an advertising thing. There’s that famous Truman Capote quote about Kerouac: “That’s not writing—that’s typewriting.” So Kerouac had to deal with that. And if you’re someone who already has a predilection to drink alcohol, it exacerbates the whole problem. I mean, these guys were pretty thin-skinned to begin with. They didn’t particularly embrace the criticism.

GO: Being famous was different then too. Now, there are degrees of fame. There’s, like, the cable-TV degree of fame, and then there’s big fame. But back then there were maybe something like 200 celebrities and you went from complete obscurity to being on the cover of Life magazine. It was extreme. There wasn’t much mid-level fame.

RP: Well, some people are better at handling the limelight than others. I mean, you take a guy like J.D. Salinger who basically has been off the grid for 30, 40 years—has no use for it, doesn’t care about it. And then, of course, it absolutely destroyed someone like Pollock. And, in a strange way, it wasn’t so much the media that did it, but just the idea of making it and becoming successful. Look at the rock ‘n’ rollers-that’s a whole other level. You can name so many who died very soon after they had any success, whether it’s Jimi Hendrix or Gram Parsons or Jim Morrison or Janis Joplin or Kurt Cobain . . .

GO: But don’t you think that while part of that is sensitivity, part of it also has to do with how being a junkie or an alcoholic has been sensationalized? You see all the pictures of Keith Richards holding a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, and it makes people think, Well, if I want that, then that’s what I have to do.

RP: And it’s amazing how many people do it, too, how many artists and musicians and people in cinema go down that road.

GO: Maybe the difference between then and now is that the abstract expressionists were all drinking gin, and today we’re drinking barrel-fermented chardonnay.

RP: Kerouac and his buddies drank Sterno—I mean cheap, cheap stuff.

GO: In Big Sur, they drink white port, which is sort of like a grape-based paint thinner.

RP: I was just reading about this drug that I’d never heard about, this herb that you chew on or something and you have an out-of-body experience for five to 10 minutes. My stepson knew all about it.

GO: Is it divine sage?

RP: It’s something like that, yeah. It was in The New York Times the other day. But, of course, where we live in upstate New York, it’s all about these meth labs. People are mixing up the medicine, cooking it in their kitchen, and getting really strung out.

GO: Everybody thinks that heroin is the most dangerous drug, but I think most of the celebrities who’ve died have died from mixing alcohol and barbiturates. That’s what Marilyn Monroe and Hendrix died from.

RP: Yeah, it’s sort of a strange way to die.

GO: So what else have you been collecting? I heard you bought Brigid Berlin’s cock-print book.

RP: Yeah. There were, like, three volumes that I bought. I don’t know how many volumes of the Cock Book she did—she might have done more than three. But they’re these huge compendiums of Polaroids and prints of people’s cocks. Everybody from Brice Marden and Jean-Michel Basquiat to Victor Hugo and Andy are in there. It kind of reminds me of Cynthia Plaster Caster.

GO: What do you think happened to those casts that Cynthia Plaster Caster did?

RP: I have one.

GO: You do?

RP: I have a Hendrix cast.

GO: Really?

RP: Yeah. She still makes them but I don’t know if you can buy them from her. She has a website.

GO: Is it a limited edition?

RP: I don’t know if it’s a limited edition. All I know is that it’s signed by her on the bottom, and it stands up like a paperweight. I was thinking, maybe down the line I would curate a show about the male physique. At this point, I have a fairly significant collection of pieces featuring the male nude. I have a Mapplethorpe. Molinier could be in there. I have Tom of Finland drawings. It’s just a subject that kind of took on a life of its own. So when the Cock Book came up, I just went for it, thinking that maybe it could be part of the exhibition someday.

GO: So you’ve lost interest in this penis exhibition?

RP: Well, I mean, that’s probably the defining area of the male anatomy that the exhibition would be about, but there was also a nice torso.

GO: You could call the exhibition “Little Richard.”

RP: “Little Richard” would be a great title.

GO: When I was in college, there was always this rumor that you could go to the Armed Forces Medical Museum in D.C. and see John Dillinger’s penis. It was supposed to be in a jar.

RP: That’s what I’ve heard, too.

GO: And it was supposed to be, like, 20 inches long or something like that.

RP: The things people save.

GO: So what’s the weirdest thing that you’ve collected?

RP: The weirdest? God, that’s a good question. I just bought a wax head of Leonard Nimoy as Mr. Spock. I bought it at an auction in Texas. It’s a life-size head, and it has the dirtiest, nattiest, most ugly hairpiece with the pointed ears attached to it. I had an entire kitchen built to house the head in the refrigerator. But probably the strangest thing I would’ve had, had I bid enough money on it, was a fence-it was the picket fence that the shooters who assassinated John F. Kennedy supposedly stood behind.

GO: On the grassy knoll.

RP: On the grassy knoll. It was taken down by some sanitation worker in the ’60s and then apparently put up for auction at a little place on Long Island. I was actually going to take that picket fence and put it up on its own little grassy knoll. But I didn’t get it.

GO: How would you authenticate something like that? Did E. Howard Hunt come with it?

RP: I don’t know-there are markings. But the whole idea of a conspiracy is so interesting. I have a copy of the Warren Report, signed to Darryl F. Zanuck [the film producer]. And then I have these strange films of people who have been given doses of LSD in a controlled environment. But probably the strangest book I own is a copy of Morey Amsterdam’s Keep Laughing because it was read by the CIA and it was all marked up.

GO: Really?

RP: I don’t know if anybody remembers the premise for Three Days of the Condor [1975] but the guy in the film basically read books for the CIA for a living. This is the only book in 30 years that I’ve ever found that I know was actually read and marked. And of all books, it was one by Morey Amsterdam.

GO: When I arrived at the Factory, Interview had published, like, six or seven issues and I was looking through the subscription list, and CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, had a subscription to Interview. I guess the FBI had a big Warhol file. But I thought it was so weird that our little magazine was being read by those readers.

I got an e-mail last night from someone saying, “ ‘Page Six’ wants to know if you just bought a G5 jet.” I e-mailed them back saying, “No, but I just bought a Power Chute.”Richard Prince

RP: Well, I guess they’d pick up patterns. There’s also a way of sending intelligence through these publications. I grew up in that whole conspiratorial atmosphere in the ’50s, being born in the [Panama] Canal Zone to parents who worked for the OSS [Office of Strategic Services, a World War II-era precursor to the CIA]. So I grew up with this kind of paranoia about communism. There wasn’t so much trust. You only hung out with your own kind, and it was a really suburban, white-bread type of existence. There was nothing foreign to the lifestyle. I would refer to it as a Reader’s Digest-type of existence. That was the only subscription that came to our house.

GO: Reader’s Digest was the biggest magazine in the world.

RP: Yeah. And it still seems kind of weird to me that someone could come out of that existence and kind of go the opposite way—you know, completely antisocial, antiestablishment, anti-Democrat, anti-Republican, certainly anti-IRS.

GO: Well, when Ted Kaczynski was a student at Harvard he apparently participated in a mind-control study where he was experimented on with LSD, and some people think that’s what made him the Unabomber. So that’s one way something like that can happen.

RP: Does anybody take acid anymore?

GO: I think so.

RP: I was the worst candidate for that kind of thing. I never had a great time on it.

GO: I took it at Woodstock.

RP: I took it at Woodstock too.

GO: It was bad. I had to leave. I didn’t want to share my blanket or be “all one.”

RP: Actually, that was one of the few times that I had a good time on it. But I didn’t like hovering above myself and looking back, or going through a door and thinking, How many times did I just go through that door? How do I get back? You know, that’s not for me. I remember that I went out to California right after I graduated from high school and that’s when I first did acid, right on Sunset Strip. I was a completely clueless teenager, you know? Drop out, tune in, turn on.

GO: Turn on, tune in, drop out, blow your mind.

RP: That’s all I knew. That’s what I wanted to do. At that point, I was a huge fan of Cream. I remember going to see them in Boston in ’66 or ’67. They were already sort of doing a much more psychedelic type of music. I liked the sound a lot. I don’t know why. There was just something about it.

GO: Well, the sound was complicated. It was a little bit like jazz—like John Coltrane or something.

RP: Well, Fresh Cream [1966] was an amazing album, but then Disraeli Gears [1967] was completely psychedelic-the songs on Disraeli Gears are a little bit more sophisticated than your garden variety pop songs. But, like we were saying, it’s interesting how someone can come out of an environment that sort of tries to shut down curiosity and imagination and channel it into something more mainstream . . . It’s funny how so many kids can just leave that behind. I mean that’s what’s sort of interesting reading about the No Wave movement in New York City in the ’70s and the early ’80s-the one thing all of the artists and musicians and filmmakers and people involved with it had in common is the sort of environment that they left behind.

GO: Yeah. We were all refugees.

RP: And they all came to New York City and disappeared into this alternative environment and started to experiment. What’s interesting to me is that it still goes on today. It might take on a little bit of a variation, but that’s what’s great about going to see new art or music or even film—the way it can now be made and distributed.

GO: But when we were coming up, I remember going to Max’s Kansas City, and all of the older artists would be sitting at the bar and the young freaks would be in the back room, but everyone was kind of in the same place, you know? Do you think that generations still have the same kind of dialogues that they did back then?

RP: I think it depends on how open you are. I mean, as an older artist, I’m fairly open. I’ve sought out and had conversations with people like Nate Lowman and Dash Snow and Dan Colen. I just met Rita Ackermann literally 15 minutes ago. But when I was younger, I was always fairly timid and withdrawn. I went to Max’s and CBGB a lot but I was always afraid—because I just didn’t fit in. One of the places that I went to was the Ocean Club—I wasn’t so much afraid there, but I could still only peer into the place where everyone ate. I remember watching Brice Marden because he had his own table.

GO: All the girls wanted to meet Brice Marden.

RP: I also remember going to Mickey Ruskin’s and seeing Lawrence Weiner and Carl Andre high-five each other. But, you know, that’s the kind of thing that gets passed on, and you start to establish your own place. That’s where places like the Mudd Club and Tier 3 and Barnabas Rex came in, because you didn’t have to stand in the wings any longer-you were a part of what was happening. I don’t have any idea where that happens in Manhattan now—I can’t even imagine that happening because who could afford to live in New York City now, you know?

GO: Maybe it doesn’t happen so much anymore.

RP: Well, if you’re an artist or someone creative, it’s all about cheap rent and not having to work for a living. That’s what it’s always been about. Unless you’re a trust-funder or you somehow score a great part-time job or you work for another artist, you’re going to go where you can afford to live. I remember coming to New York. The plan was to come here for three months-if I could last that long. I remember saving $2,000 and saying, “Well, I just want to check it out.” I’d read about this thing called SoHo and I just came down here . . . I sublet an apartment from this guy who made porno films, and he charged me $140 a month. I was outraged because it was a roach-infested, tub-in-the-kitchen piece of crap, and I was used to paying $60 a month in Boston. And I couldn’t afford it. But I couldn’t find anything cheaper. So I guess it’s all relative.

GO: So what’s your rent now?

RP: I don’t rent, and I don’t own, and I don’t have a mortgage.

GO: Yeah, I know.

[Leonardo DiCaprio enters.]

LEONARDO DICAPRIO: ‘Sup, buddy?

RP: Do you know Glenn O’Brien?

GO: Hi.

LD: Hi, how are you?

GO: Good, nice to meet you.

RP: Leo, this is his magazine. [shows DiCaprio a copy of Interview]

LD: Right. I was speaking with Mr. Tony Shafrazi about that.

RP: You want something to eat?

LD: Sure, I’ll eat something. Tobey [Maguire] can’t make it until later now.

RP: That’s all right. [looks at plate] I don’t know what that is but it’s—

LD: Fishy?

RP: I don’t know. Is it fish?

GO: I think it’s roast beef, isn’t it?

RP: Is it roast beef?

GO: Ham?

RP: Ham? Turkey?

LD: Is this eaten?

RP: Nope.

LD: I’ll eat this. The magazine looks great, though.

GO: Thanks.

LD: It’s going back old-school now, right?

GO: Yeah.

LD: That’s great.

GO: Somebody e-mailed me that Kanye West has a blog and on the blog today he says Interview magazine is the shit.

RP: Oh yeah? He just got arrested.

LD: Kanye West did? What for?

RP: Paparazzi.

GO: Punched a photographer at the airport, allegedly.

LD: Good for him.

RP: Yeah, more power to him. But that’s the weird thing about celebrity. I got an e-mail last night from someone saying, “ ‘Page Six’ wants to know if you just bought a G5 jet.” I e-mailed them back saying, “No, but I just bought a Power Chute.” Ultimately, though, people stop talking about what you do and start talking about your lifestyle. Luckily for me, I don’t really have a lifestyle.

GO: But you were prepared for fame from years of lying.

RP: Well, that’s true, yeah. I mean, it gets back to that issue of how you deal with it. Obviously, the art world is a bit smaller than the music world, and the music world is a bit smaller than the cinema world. But the art world is pretty tight even though the biggest thing that’s happened to it is the auctions, which are the only reason people on the outside know anything about it.

GO: But in the old days people knew who Picasso was, right?

RP: Well, the way you would know if someone is famous in the art world is that you would ask your mother. My mother knows who Picasso was. She knows who Warhol was.

GO: What about Julian Schnabel?

RP: No.

GO: [in funny accent] You know, Mom, that guy in the pajamas?

RP: But she knows who Rauschenberg was. My mother knows who Larry Rivers was, which is interesting. I think Larry Rivers was one of the most underrated artists.

GO: She knew him because he was a looker. Do you get people coming up to you more now than you have in the past?

RP: I’ve had to put up security at my house upstate—you know, it’s on a dead-end dirt road in the middle of nowhere. Leo just went up there, and he can attest to the fact that I live in the middle of God only knows where. But we had a guy from Germany come down the driveway the other day.

LD: [in German accent] Mr. Prince! I love your work! A moment of your time, please!

RP: [laughs] Exactly. But I think with success you do get a little more guarded and you start to change your friends. You become more isolated. And you start hanging around with people who have money! I think that’s the biggest thing. Once you do get a bit of change in your pocket, you start hanging around with other people who have some change. It was kind of strange to all of a sudden go from one extreme-Manhattan-to where I went, upstate New York. But I did it because I was dying in the city. I couldn’t take it. I couldn’t take one more dinner party. I couldn’t take one more party, period.

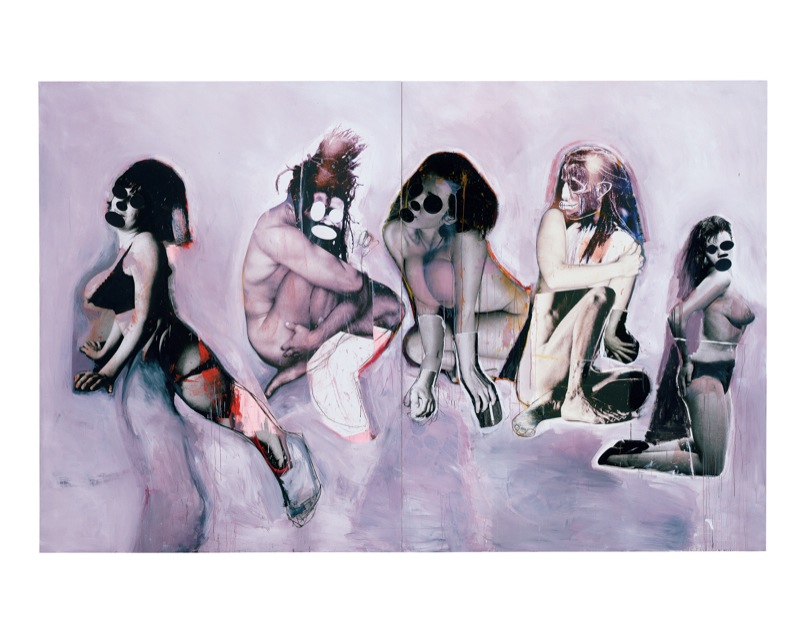

The Rastas and the lesbians started starring in these pictures and were kind of like bands-there are, like, five people to a picture, and every picture has a title to it. It sort of becomes an allegory. It’s just something I needed to get out of my system.Richard Prince

GO: Also, you were clearly hypersensitive. Richard had three floors in his building so that nobody would be above him and nobody would be below him-so he didn’t have to hear anybody walking or playing music.

RP: Yeah, I was very sensitive about noise, which, if you’re going to live in New York, is crazy. But I paid so much money for that situation. And then I ended up renting to the strangest people. I rented to the woman who played Laura Palmer on Twin Peaks, Sheryl Lee. But I do remember things about living in New York . . . I remember being at the Odeon one night and going down to that basement and pissing in one of those old toilets up against the wall with the ice. It was called pissing on ice-that was the expression. A really good restaurant pours ice in their toilets, at least on the men’s side.

LD: Is that true?

RP: That’s the mark of a very upscale restaurant. It’s not true anymore but it used to be.

GO: They still have it at P.J. Clarke’s, I think.

RP: Apparently, it takes away the ammonia smell of urine. I used to write under the pseudonym of

Fulton Ryder, and I wrote a little essay called “Pissing on Ice” that was published in Real Life magazine.

GO: Hilton Rider?

RP: Fulton Ryder.

GO: Fulton. So how did you get into these Rasta pieces that you’re doing now? I know a little bit about it.

RP: That was just from hanging out in Saint Bart’s for the last 12 years.

GO: And we all know how many Rastas there are in Saint Bart’s . . .

RP: There aren’t that many Rastas in Saint Bart’s, but I picked up a book on them. It’s a very foreign subject for me. And, you know, I just love the mysticism—the kind of religious, musical definition of Rastafarianism. It’s a very defined type of culture that I didn’t really know much about. But I loved the look, and I loved the dreads, so I just started fooling around with this book, drawing it like I did with the de Kooning paintings. I did some collages. And then I wrote this proposal, which I pitched to Hollywood. It was called Eden Rock. The story was basically about a guy who lands in Saint Bart’s, gets off the plane, is immediately told that there’s been a nuclear holocaust in the rest of the world, and he looks at his family and says, “We can’t go back.” So he and his relatives take over a hotel—they take over Eden Rock. Then there are some Rastas on a cruise ship. Three days later, some locals attack the cruise ship and they start throwing people overboard. And these are huge cruise ships down there-like, multi-level cruise ships. But the Rastas escape, and they take over their own hotel, the Manapany. And then there’s a lesbian group of girls who escape and they take over their own hotel, the Guanahani. So everybody has their own hotel, and that’s where the video game rights come into this pitch. We got a ghostwriter to do the story, and it’s being published, and eventually, hopefully, it’ll be totally fucked up by Hollywood. But I don’t care because it’s all under a pseudonym. My name is not attached to it.

GO: Fulton, uh . . . Ryder?

RP: Fulton Ryder is the pseudonym. So anyway, the Rastas and the lesbians started starring in these pictures and were kind of like bands—there are, like, five people to a picture, and every picture has a title to it. It sort of becomes an allegory. It’s just something I needed to get out of my system. The pictures are very quickly done-they’re not really thought about—and there’s a collage element to them that’s very primitive. Paste-up, cutting with scissors, and squeegeed on with paint. It’s something that I can do myself, and I like that aspect of it. I don’t need assistants. I don’t need anybody. “James Brown’s Disco Ball” is sort of the working title of the whole body of work, although “Ding Dong the Witch Is Dead” is another title that I’m thinking about. And then my contribution to the Rastas was this introduction of the guitar.

GO: Is it always the same guitar or are there different guitars?

RP: No, there are different guitars. I cut out the little section of the guitar and pasted over their midsections, so it’s like the new fig leaf.

It was kind of strange to all of a sudden go from one extreme-Manhattan-to where I went, upstate New York. But I did it because I was dying in the city. I couldn’t take it. I couldn’t take one more dinner party. I couldn’t take one more party, period.Richard Prince

GO: What about the eyes?

RP: I had done the lozenge eyes for your book of poems a long time ago. I also did a whole portfolio of historical Jesus paintings that I put these lozenges on. And then, of all people, Marc Jacobs was in the studio, and I must have had one of these lozenge faces out, and he says, “What’s this? I’ve never seen this before.” He really liked it, so he made some jewelry with it. It sort of got me thinking about them again. The other thing is that a lot of the imagery is black-and-white, so the lozenge is almost like one of those old black bars that they used to put over women’s faces in porn magazines if they didn’t want to be identified. I like the idea-it’s almost like it has this kind of relation to the nurses’ mask [in Prince’s nurse paintings]. It’s a way of making it all the same and getting rid of the personality. It also comes out of the de Kooning paintings. It really morphed out of that because right at the end of working on the de Koonings, I started to use images of black women with a black-and-white process. I liked the skin tone that came out of the ink-jet process-it was just something accidental.

GO: Why did you get sick of doing the de Kooning paintings? It seemed like you did more nurse paintings than de Koonings.

RP: Yeah, I did do more nurses, but with the de Koonings, I’d just done it. I didn’t like the idea that, in the end, I had to pay attention to someone else’s work. And I wanted to get rid of the color. So the thing is that, you know, two years of doing the de Koonings was enough. It was enough of my attention. The Rastas came really fast. And they’re going to be over really fast, too.

GO: The last time I was at your house on Long Island, you had this Velvet Underground painting up. And then I saw it on an auction link right after that.

RP: That’s because it was donated to the red auction. I still occasionally do a Velvet Underground painting. I’ve done a Sonic Youth painting and two of The Band. Those are the three bands that I’ve done.

GO: I was listening to Sirius Satellite Radio the other day and “When I Paint My Masterpiece” came on. What a great song that is! The Band and Bob Dylan. Dylan wrote it. The Band covered it. Then Dylan and The Band did it together.

RP: The Band had great songs. They had great album covers, too. I remember the second album [The Band, 1969] that came out with them standing in the field, sepia-toned. They looked like they were out of that McCabe & Mrs. Miller [1971] western with Warren Beatty. It was a very simple cover, just them staring at the camera. You really couldn’t tell who was who.

GO: Did you ever go up to Woodstock when they were living up there and hanging out?

RP: We go down to Woodstock like once every two months. It’s pretty near where we live. I’ve always wanted to go back to the field where the original festival took place in Bethel [New York], Max Yasgur’s farm. Apparently they have a marker there now and it’s a public space. I always wanted to go back there. I wanted to go back to that field and take a photograph of it. The same place where I took my one photograph of Woodstock.

GO: With the one frame that you had left in your camera.

RP: You don’t believe that, do you?

GO: After all these years, there are a couple of things that I’m still not quite sure about.