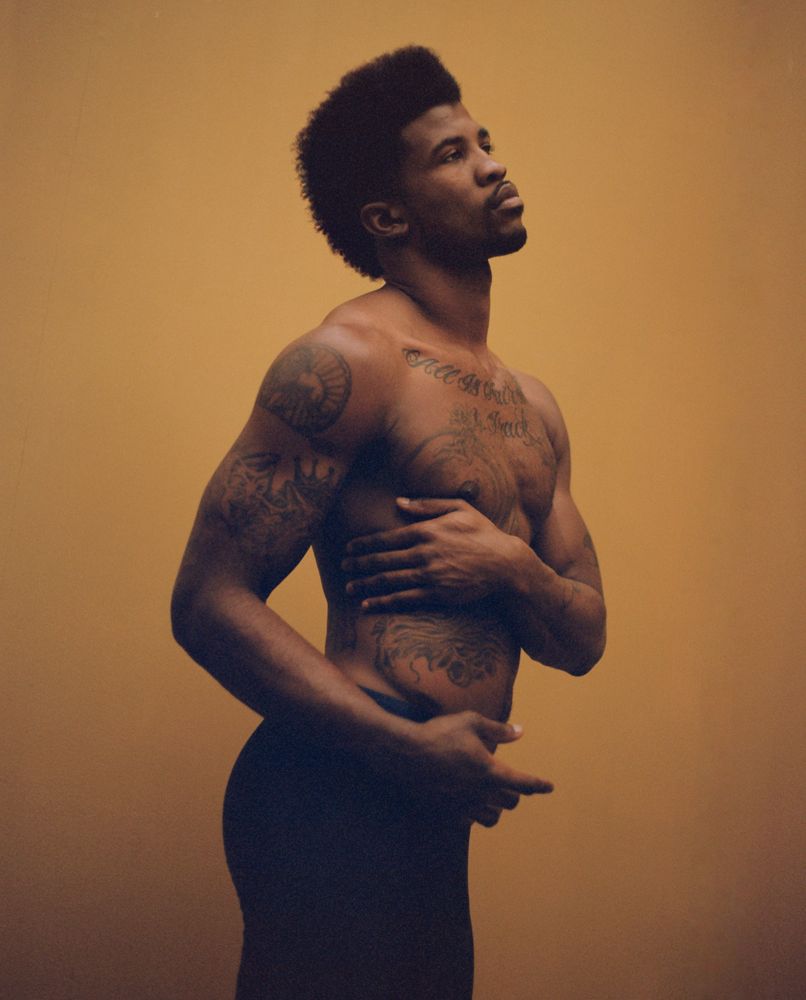

The Paralympic Champion

RICHARD BROWNE JR. IN NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2015. PHOTOS: THOMAS WHITESIDE. STYLING: IAN BRADLEY. LAURA DE LEON FOR CHANEL/JOE MANAGEMENT USING SOLUTION 10 DE CHANEL.

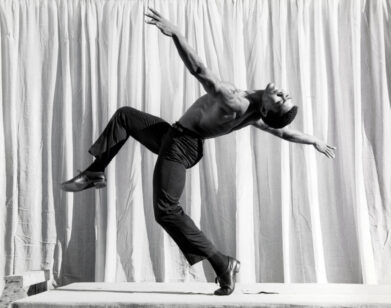

As American sprinter Richard Browne Jr. gets ready to race, the first thing you notice is his build—unlike distance runners who are small and wiry, Browne is 6’3″ and nothing but muscle. The 24-year-old Jackson, Mississippi native looks like the running back of an NFL team. Once the whistle blows, however, and Browne starts to run, the only thing you can think of is his speed. Take, for example, the 100-meter final at the 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships in Doha in October: Browne thrashed his competition, winning by more than you would think is possible in just 100 meters. Currently, he holds three T44 world records: the 200-meter sprint (21.27 seconds), the 100-meter sprint (10.61 seconds), and the 60-meter sprint (6.99 seconds). “The only sprint record I don’t have is the 400-meter,” the athlete explains. “I want that one too, to be honest.”

If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard of Browne or seen him on Billboards in Times Square, the answer is depressingly simple: Browne is a para-athlete; he had one of his legs amputated in 2010, following an accident in 2007, two weeks in a coma, two months in the ICU, and 14 surgeries, and runs with a blade. “I did everything possible to save my leg,” he recalls. “[But] in 2010, I was a freshman in college and not able to live my life the way any 19-year-old would, so I decided to get it cut off. It was the best decision of my life.”

Browne wasn’t a runner before he lost his leg (he had played football, but was never passionate about it). The second eldest of 10 children, Browne planned to be a math teacher and studied physics at Morehouse College in Atlanta. Two years after his amputation, however, he took home a silver medal at the 2012 Paralympics in London. Although the United States did show Browne’s win retrospectively, they did not televise the majority of the games (NBC showed five and a half hours of taped highlights, which, when compared to coverage broadcast by Channel 4 in the U.K., seems pretty feeble).* The upcoming 2016 games in Rio will be the first time the U.S. has shown the Summer Paralympics live on television since Athens in 2004 and is slated to receive over 60 hours of coverage.

“Most people [in the U.S.] don’t know we exist—it’s worse than being ignored,” says Browne. “I remember coming back from the 2012 Games. The whole team, we flew back together, and people were like, ‘Are y’all some kind of special team?’ The Paralympic Games is the biggest sporting even in the world, we just represented our country, and when we get back to that country, no one knows what happens.”

At the moment, Browne is based in Cambridge, England, where he is working with a new coach experienced in training para-athletes Hayley Ginn. Needless to say, he is a favorite for Rio.

EMMA BROWN: Did you like growing up with so many siblings?

RICHARD BROWNE JR.: It was awesome being in such a big family. We’re super competitive amongst the boys. All of us play a different sport, whether it’s football, basketball, or track. It keeps you on your toes because you have your younger brothers that want to be better than you and then you want to be better than your big brother. It keeps us going. At Thanksgiving and Christmas we always play football and basketball. That’s the tradition amongst the boys. The girls, they’re usually girls—except my sister Cheyenne, she runs track for Ole Miss, and she’s usually with the boys. My other two sisters are super girly-girly.

BROWN: When did you start running?

BROWNE JR.: 2010. I lost my leg in February of that year and six months later I was in Edmonton, Oklahoma for my first track meet ever.

BROWN: That’s so quick!

BROWNE JR.: It was a quick turnaround. I got my walking, every day prosthetic and I was playing basketball again and playing football. My prosthesis said, “You know they make running legs. You should try it out. They have track meets.” I Googled it and came up with Oscar Pistorius and Jerome Singleton and April Holmes and Marlon Shirley. I’ve been running ever since then. I didn’t know anything about U.S. Paralympics, or any Paralympics, actually, before losing my legs. It fell into my lap. It was a gift.

BROWN: When did you first consider becoming a professional runner?

BROWNE JR.: Honestly, it was my first coach ever. I went to Disney and ran at a meet there. I think I went 11.40 [seconds in the 100 meters], which was a fast time back then but today is not very fast. He was there and he was like, “I’ve been wanting to coach a Paralympic athlete and you’re here now, so I feel like this is us crossing paths for a reason.” I’m a true believer in everything happening for a reason, so when he said that, I packed my bags and went back to Orlando to train for the 2012 Paralympic trials in Indiana. I trained hard for about two months with him, and then I ended up making the team, going to London, and winning a silver medal. You can say I turned pro after the games in 2012. It was a really quick turnaround. I went to Crystal Palace in London, England, that was my first-ever international meet, my first time out of the country in my life. The guy who beat me was actually Jonnie Peacock, the Paralympic champion, and I came in second to him again the following year.

BROWN: I was reading some of your past interviews, and a few of them talked about your rivalry with Jonnie Peacock.

BROWNE JR.: Yeah, I really don’t like Jonnie. Me and him have been in the sport together since 2011, so it’s hard to say I don’t like him as a person because we’ve really broken down doors—before us, besides Oscar, there really weren’t any fast runners. Jonnie Peacock was the first to ever really push the barriers—he went 10.85, and that was the first time we really thought a single leg amputee could run that fast. When I came along, I began to run 10.7s and that kind of fired everything up between us. I was the world recorder holder; he was the Paralympic and world champion at the time because he beat me in 2013 by .01 [seconds]. I think that race in 2013 is what really started the rivalry. It was such a close race. It was really intense World Championships because we were the favorites going in. As far as now, I love beating him. I’m not going to lie. When he’s on the track, I do push a bit harder. There’s definitely still a rivalry there.

BROWN: But it’s just on the track?

BROWNE JR.: I wouldn’t go out for a beer with the guy, but it’s mostly track. We’re very, very different people. He’s more the true British guy and I’m the American loud-mouthed jock. Our contrasting styles make it a rivalry; it’s the American vs. the Brits. It’s just a lot of different layers to the situation. But it’s awesome for the sport. Since the rivalry started the world record has dropped two-tenths of a second, and it’s only been over the last year and a half. It’s been pretty quick in advancing the entire sport, and now you have the younger guys—Felix Streng from Germany, Arnu from South Africa—who are wanting to run fast.

BROWN: Looking at videos of you racing the 100-meters in Doha, you won by so much it’s hard to imagine anyone being a threat. Is there anyone you’re looking out for in Rio?

BROWNE JR.: Not in the 100 meters. You have Jarryd Wallace, my fellow American, and he ran 10.71 in the Pan-American games this year in Toronto, but honestly I feel like I’m a head above the rest at the moment. Even with my performance in Doha, I was only working with my new coach in Cambridge for about three weeks and we changed so much and got so much faster. I went from 10.72 to 10.61 over three weeks, and it was a few technical changes here and there in form—we didn’t really train hard. Now that we have better form, we can train hard and get faster. I really haven’t had any consistent training because I keep having kids. [laughs] I have three beautiful kids and they push me very hard.

BROWN: How old are they?

BROWNE JR.: Three, one and a half, and then my new son are only about two months. I have two boys and a little girl. I won’t have a family as big as my family, but at this rate…but it’s been amazing. The only thing I don’t like is I made the sacrifice to move to Cambridge for my career, London being the epicenter for para sport. It’s been a good move for me, but it’s been hard to be away from my kids.

BROWN: Is your three-year-old old enough to understand what you do?

BROWNE JR.: He is a track fanatic. He does, “Set, go!” He loves to get into blocks with me. He was at nationals with me. He came to worlds with me. He loves track and field. I remember calling him right before the 100-meter final [in Doha], because he went home, and he goes, “Go Da-da, go!” Now my daughter’s starting to say, “Set, go!” Hopefully I’ll have a couple of runners in the 2036 Olympics.

BROWN: Do you think the Paralympics should exist separately from the Olympics? Or should there be Paralympic events in the Olympics?

BROWNE JR.: The only reason I would say keep it separate is because we are separate. No matter how hard I try, I can never be as good as a Bolt.

BROWN: You’re pretty close.

BROWNE JR.: I’m close. I want to get even closer. But despite how good we are, our disability will always limit us. We can get very, very close to that limit, but it’s still going to be there. It’s one of those situations where I do think we should remain separate and let us be our own entity. I just think the people who are in charge can do better things to get us to the world. The American public really don’t know what para sport is. They think we’re part of the Special Olympics—and nothing against the Special Olympics, but being mentally and physically disabled is different. America as a whole needs to wake up, not only to disabled sport, but disability in general. We’re bigger than our disabilities. Everyone out there has a story, but we’re bigger than our story.

BROWN: Did people treat you differently in your day-to-day life after you lost your leg?

BROWNE JR.: Definitely. I think the biggest thing to get used to was being stared at because you have one leg or you have a disability or you’re in a wheelchair or you’re blind. Any Paralympian you talk to, no matter what their disability is, I think that’s the biggest part—just being different from the general public. Then after you get past that, it’s, “Oh wow, you’re an athlete on top of that?” You don’t want people to be like, “Oh, that’s so great, we’re just happy that you’re here,” because you’re good at what you do. It’s a catch-22; you don’t want to just be looked at because you are disabled but you are disabled so you have to be looked at. It’s really hard to deal with mentally—you really, really want to be looked at as a normal athlete, but you’re not a normal athlete, so how do you go about it?

BROWN: But you look like an athlete. You like an Olympian.

BROWNE JR.: The rigorous training that we go through is the same that a [Usain] Bolt will go through, Justin Gatlin, Allyson Felix. I literally trained with Gatlin for a year. Everything he did, I did. He had the best season of his career; I had the best season of my career. We do everything an able-body does, it’s just we have one leg or are in a wheelchair or whatever the case might be.

BROWN: How did you meet your new trainer Hayley Glinn?

BROWNE JR.: I’ve actually known Hayley since 2012, we met through Jonnie Peacock—she was around the games and we built a relationship over the last three or four years. She’s pretty much the most knowledgeable person in the planet when it comes to running mechanics with a blade, and I’m at the point now where I’m pushing conventional knowledge—no one thought an amputee could run faster than 10.5, and now it’s, “Oh, when is Richard going to run 10.3, 10.2.” And she’s the coach that’s going to get me there because I have to worry about different equipment. Unlike an abled-body, I have my prosthetic leg to worry about and I have to change the angles on it to be able to do certain things. Just those extra idiosyncrasies that an able-body doesn’t have to worry about and a normal coach wouldn’t know, she knows everything about. We made a couple of changes here and there and I dropped a tenth of a second so it’s been working pretty well.

BROWN: Do you customize your running leg?

BROWNE JR.: Everything is pretty much custom on my running leg, [or] any prosthetic. A lot of amputees don’t know that they can be as finicky and as particular as they want to be about their prosthetic. I’m one of those people who is very particular. You could put a penny in my leg and I would feel the difference. You get very, very close with your leg. My leg even has a name, we call it Earl. My leg is my livelihood, my best friend, my training partner. My leg is the most important piece of equipment I have, without it I can’t run. We do very, very strenuous testing and working with my leg—the angles and how it fits and all those different things.

BROWN: What made you finally decide to move to Cambridge?

BROWNE JR.: I hit a wall. I got to 10.7 and I couldn’t go any faster, which is fast enough to beat everyone I’m racing against, but I like to push—I want to go faster. I’m going to go 10.2 in Rio and 20.1/20.2 in the 200. Alan [Fonteles Cardoso Oliveira] from Brazil says he’s going to go 19 seconds. In the 100, I don’t have any competition. In the 200, it’s going to be a battle between me and the Brazilian and he’s the hometown favorite. I love going to Rio; I’ve been Rio about four or five times over the course of my career and it’s absolutely beautiful down there and the people are super supportive of Paralympics, but him being the hometown favorite…I remember running against Jonnie [Peacock] in 2012, and when they called his name the crowd erupted, the ground shook under my feet, and I can remember saying, “Wow. I really hope America gets the Olympics before I retire, because to run in front of your home crowd, that has to be amazing.”

BROWN: In one of your interviews, you said you preferred the 200-meters.

BROWNE JR.: Oh, definitely. The 200 is my baby. I love the fact that I can actually race. The 100 is pretty much get out and go; it’s over before you can even think. In the 200, you have time to prepare. It’s still an all-out sprint, but it’s a tactical race.

BROWN: Is it hard not to get complacent when you win a race by so much?

BROWNE JR.: At first, it was. But I remember Gatlin pulled me to the side one day in practice and was like, “When you’re the best at what you do, you have to race yourself. Every day you wake up and look in the mirror, and that’s your competitor. You’re still not the best in the world, because you’re looking at somebody every day that you can be better than.” My mom, as well. If I brought home a B, I got in trouble. My first grade that wasn’t an A was my freshman year of college. I remember quitting track when I first started running, and she was like, “We don’t quit things. That’s not something that you do in anything you do.” I know what goals I want to accomplish: I want to break the 10-second barrier. I want to break the 20-second barrier. When I see 9.9 come across the clock, I’ll stop. But until then I’m going to keep training hard and I’m going to push those conventional theories that “amputees can only run…” If it’s not me, I do think an amputee could break 20 seconds or 10 seconds.

BROWN: Why were you considering quitting running?

BROWNE JR.: It was really hard, just getting up every day and putting your body through that voluntarily. Track isn’t like other sports; other sports natural talent takes over at some point. Sprinters are born—you can’t make someone into a sprinter. I was born with all the right muscles and nice levers, but now I have to train those things and my body has to be very coordinated and all those things that you can’t just do by going out on the track. You have to train your body for that. I think that’s the hardest part. Everything had come easy to me for the first 19 years of my life. Now that I was actually having to work hard at something, I didn’t know how to feel.

BROWN: Did football come easily to you?

BROWNE JR.: Yes. I played football my entire life. I didn’t have to go to practice. I could just go to the field and be better than everybody out there. I never wanted to be a professional player. I didn’t think that was in the cards for me. I probably had the ability, I started on the varsity team as a freshman, so I was always good at it, but I didn’t want to work hard. When I lost my leg and track was placed in my lap, it was the universe showing me, “You need to work hard at something.” I don’t think there is such a thing as having a life plan; you pretty much have a purpose in life, and I think this is my purpose—not to be great on the track, but to be someone who touches people’s lives. I’ve taught kids how to walk, run. I’ve shown people that there’s life after disability. I’ve walked into a hospital and people are crying because they just lost their leg, and it’s like, “Look at me, you can walk around.”

I think my biggest goal in life, even with that photo shoot we just did, is to show that you can still love yourself, you can still be an awesome person and whatever you want to be despite your physical disability. Especially when it comes to physical appearance, because I know a lot women, their biggest hang-up is that you’re changing physically how you look. As soon as you look at me, if I have on shorts, you can tell that I’m disabled and you’re going to judge me by what you see before I say anything, before you know who I am. It’s the same for every physically disabled person—anyone sitting in a wheelchair, wearing a prosthetic, blind. Before you see us, you have a pre-conceived notion of “Aww” or sympathy; it’s just how humans are. Especially with kids, because kids are mean. And I have three. To grow up being a kid and being different, I’ve talked to kids who try to hide their prosthetic with things like long socks, but I let kids know that you don’t have to. People say I’m flashy and I’m a showoff on the track—it’s not that, I’m just really showing appreciation for being alive and the opportunity that I’ve been given: to travel the world running track, to do something I love and get paid for, to touch people’s lives every day. It’s one of the best feelings in the world. A little girl told me once, “I want to cut my leg off just like you.” She wore braces because she didn’t want to get her leg cut off, but when she saw me, she was like, “I’m going to get it cut off now.” When you can show people it’s okay, that’s the best thing.

BROWN: Did anyone do that for you?

BROWNE JR.: Actually, no. I’ve always taken things in stride. I grew up, not hard, [but] my mom worked three jobs to take care of us. We didn’t have everything we wanted but we had everything we needed, so I’ve always learned you do the best with what you have. I had that instilled in me as a young child from my mom and my grandmother and I’m thankful for that. I’ve always been a kind of in-your-face guy, but I began to tone that down for some odd reason, I don’t know what it was, and people really noticed it. People want a show, people want to have somebody to look to and have that thought of, “It’s okay, I can be as strong as I want to be.” Some people need that person, a role model. I don’t like being called a role model, I don’t like being called an inspiration, but those are the things I am now because of what I do. It’s really just kids. I’ve talked to women about their legs, and I’ve talked to some guys. Most guys are more concerned about things they can do: “I want to be able to go back to work, and am I going to be able to walk?” You can do anything you want to do with a prosthetic; it’s just those mental things.

BROWN: Are you close with your mother?

BROWNE JR.: Not very close. The only reason I’m not close is because of my accident. She still feels like it’s her fault. She was there when I initially had my accident. The thing is, she did so much for me. She took care of me when I was fighting for my life—literally—every day. She lost her house because I was in the hospital for about three months straight. I lost so much blood that no doctor wanted to touch me. They were like, “He’s going to die.” So my mom had to beg doctors to operate on me, because everybody thought I was a hopeless case. So for her to go through that, she’s amazing. But she’s so scared. She saw me fall on the track—she’s super supportive of my career, she has all my medals and my pictures and my posters, but she’s just like, “Richard, I want you to come home so I can take care of you for the rest of your life.” Like any mother would. I have kids and as soon as they fall I just want to take them and hold them. But being a parent, you have to let your kids go at some point.

FOR MORE ON RICHARD BROWNE JR, YOU CAN FOLLOW ON HIM ON TWITTER OR VISIT HIS WEBSITE.

For more from our 16 Faces of 2016, click here.

* This article previously incorrectly stated that the U.S. did not televise the 2012 London Paralympics and has not televised the Paralympics since Athens in 2004. They in fact showed 5.5 hours of taped coverage for London and televised the Sochi Winter games in 2014.