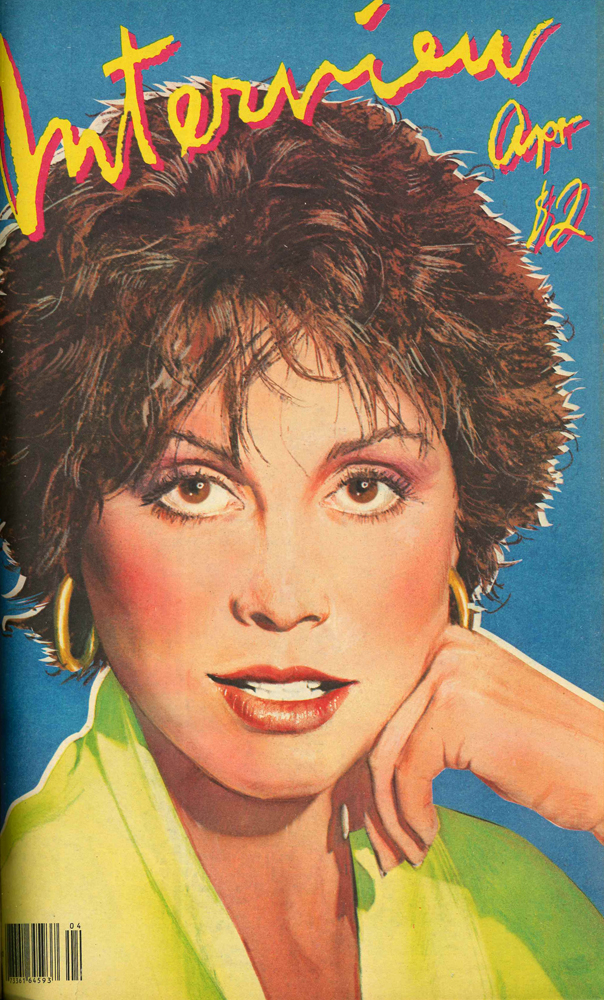

Remembering Mary Tyler Moore

Mary Tyler Moore, the pioneering actor and an auteur of modern comedy, died Wednesday at age 80 at her home in Greenwich, Connecticut. Trained as a dancer, the New York native broke out in showbusiness with her role as Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show, but cemented her status as a television icon on her eponymous sitcom, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, where her spunky character Mary Richards subverted expectations of what it meant to be a modern woman in the more-shifting ’70s. Today we revisit Moore’s April 1981 cover story in Interview, conducted shortly after her Oscar-nominated role in Ordinary People debuted, in which she runs about town with our founder, Andy Warhol, chats with a cop, and more.

The New Mary Tyler Moore

By Andy Warhol

Monday, February 23, 1981, 8:30 PM. Mary Tyler Moore is dining with Andy Warhol, Brigid Berlin, and Ara Gallant at John’s Pizza, 278 Bleecker Street, Greenwich Village. Dessert follows at Serendipity, 225 East 60th Street. Mary is wearing a burgundy plaid shirt, beige corduroys, honey-colored boots, a silver Cartier watch and silver earrings, and carrying a Louis Vuitton bag.

ANDY WARHOL: You own this place?

PETER CASTELLOTTI: Yes I do, Sir.

BRIGID BERLIN: When did it open?

CASTELLOTTI: 1934.

WARHOL: You’ve had it since 1934?

CASTELLOTTI: No, my uncles had it. They moved out for the young.

BERLIN: Is everything homemade?

CASTELLOTTI: Yes. Have you tasted our pizza?

BERLIN: No.

WARHOL: She hasn’t eaten for three months. She used to weigh 500 lbs. Now she weighs 135.

CASTELLOTTI: I don’t believe it.

BERLIN: My top weight was 260 lbs. I’ll come here on my next binge.

CASTELLOTTI: You must have a slice.

BERLIN: Do you just serve pizza? If I eat a slice, I’ll eat the whole pie. It’s all or nothing.

CASTELLOTTI: No, we have spaghetti, ravioli, manicotti.

BERLIN: What’s that big white pie over there?

CASTELLOTTI: That’s calzone. We got a write up two weeks ago in The Times in Mimi Sheraton’s column.

BERLIN: If you’re supposed to be the best pizza in New York, why has Ray’s Pizza gotten all the publicity?

CASTELLOTTI: I’ve worked here 25 years and now I’m a partner. I’m looking to expand and find a store uptown. We’re going to shake Ray up a little. We’re going to give him a run for the money.

BERLIN: I’ve never been a pizza eater. I don’t like to hold it and fold it and always burn the roof of my mouth. I hate having greasy fingers. Here comes Mary and Ara.

MARY TYLER MOORE: Hi, Andy and Brigid. it’s so nice to meet you both.

ARA GALLANT: Hi. This is such a great place. What makes their pizza so good is the oven. They have this old oven that works on wood. You can’t get this oven anymore, it’s unique.

MOORE: Fifty variations, I can’t stand it. It’s like going to Madame Romaine’s for omelettes.

GALLANT: I like my pizza plain. It’s so good here. I like it in its purity.

MOORE: When you say plain, what do you mean?

GALLANT: Nothing on it, just tomatoes and cheese.

WARHOL: The white one looks really good. We should get two pizzas.

MOORE: Maybe we should get six.

WARHOL: Let’s get six.

MOORE: I have been looking forward to it for so long. He only has whole pies, no slices. That’s too bad.

WARHOL: There’s always a line around the block. Because of the rain there’s no line.

MOORE: So we came here on a good night.

GALLANT: Mary, what would you like to drink?

MOORE: Some red wine would be lovely.

GALLANT: I’ll have beer. A Bud would be great.

BERLIN: I’d like another Tab please.

MOORE: I should own stock in Tab. I go through about six a day.

BERLIN: I beat you.

MOORE: I heard about a man who lived in this enormous house who claimed that his life was saved by Tab. Do you remember when the ban on saccharin came in and they were going to take it off the market? He was addicted to Tab so he bought I don’t know how many thousands of cases and put them all in his cellar. One night his house caught on fire and what saved his life was the sound of the exploding Tabs in the basement. Other than that he would not have known and wouldn’t have gotten out. I did a similar thing when that ban came out. Not to that scale or degree, but I loaded myself.

BERLIN: I haven’t had a Coca-Cola in ten years.

MOORE: I had one by mistake the other day and it tasted very strange to me.

BERLIN: I use incredible amounts of Sweet ‘N Low and saccharin in coffee.

MOORE: I do too. Especially on those nights when I break with my discipline and have chocolate mousse, I’ll have Sweet‘N Low in the coffee.

BERLIN: I do the same thing.

WARHOL: But you gain ten pounds a night. Brigid hasn’t eaten anything but cottage cheese for months.

MOORE: What about your energy?

BERLIN: I feel wonderful.

MOORE: How much weight have you lost?

BERLIN: Thirty pounds in a month. It’s hard for me to keep it off, though, I’m a binge eater.

MOORE: Well, I think we all are.

WARHOL: She goes to AA and OA.

CASTELLOTTI: What kind of pizza would you like?

MOORE: It’s my first time, what do you recommend?

CASTELLOTTI: How about sausage, mushroom, peppers, onions, meatballs, anchovies?

MOORE: No anchovies. Do you do salad?

CASTELLOTTI: No.

GALLANT: We’ll do one of those and one plain.

WARHOL: Let’s have a calzone, too.

BERLIN: You can take home what you don’t eat.

GALLANT: Oh yeah, take home is always great.

MOORE: Do you eat it cold or heat it up?

CASTELLOTTI: Oh, it’s better cold.

MOORE: Do you think I can handle heating it up? You saw my performance with the ribs the other night.

CASTELLOTTI: Mary, you look better in person.

MOORE: Thank you… I think.

WARHOL: When did you come to New York?

MOORE: It was just about a year ago. I started with the play, Whose Life Is It Anyway? and that was only supposed to be twelve weeks. It was so successful that it was extended to four months. During that time the seduction took place and I decided I couldn’t leave New York.

WARHOL: I thought you did Ordinary People afterwards.

MOORE: No, the movie was first. I’ve been here the whole time. I’ve gone back several times for visits and to exchange winter clothes for summer clothes and that kind of thing. But the big news is that I just bought a place. I’m going to sell the house in California and become a fulltime resident of New York.

BERLIN: Weren’t you subletting for awhile?

MOORE: During the summer I was subletting from Marjorie Reed. I stayed there for three months.

BERLIN: Was that the apartment that overlooked Nixon’s backyard?

MOORE: Yes. I didn’t have the courage to go knock on his door and say I’d like to talk to you.

WARHOL: I never saw you walking in the neighborhood.

MOORE: I walk a lot. I have no problem walking in New York because I have a very brisk pace: By the time anyone recognizes me, it’s too late, I’m four blocks away from them. You must be recognized a lot.

GALLANT: Mary has a very determined walk. Her walk is very interesting.

WARHOL: It’s funny when people don’t know you and they meet you for the first time and think you’re so great. When fans know you for more than three or four times the magic is gone.

MOORE: Oh, sure.

WARHOL: Why can’t it just be magic all the time?

MOORE: Well, because with fans they want you to be something super-human, something that’s impossible for any human being to be.

WARHOL: it would be great to be super-human, to give the fans just what they want.

GALLANT: You wouldn’t want to give them what they want.

BERLIN: They don’t know what they want either.

GALLANT: They have to take what they can get.

MOORE: Which is the performance… I think.

BERLIN: You were superb in Ordinary People. I really hope that you get the Academy Award.

MOORE: Thank you. I don’t think there’s any chance of that.

GALLANT: I think it’s interesting being nominated. Whatever happens in the next step happens.

WARHOL: You’re about the only actress who’s ever come from television into movies.

GALLANT: No, she did movies.

MOORE: I’ve done a few but nothing of any particular note except for A Change of Habit in which Elvis played a singing surgeon and I was a nun.

BERLIN: What year was that?

MOORE: 1969 I think. It’s been on television a lot.

BERLIN: I saw you in the Betty Rollins story, First You Cry. That was a very moving performance.

MOORE: Thank you. I cared a lot about that project. I felt from having read the book that if it were to happen to me or somebody close to me that I would handle it much better so I wanted it to reach more people which you can only do through television. There was one other movie though that I really am proud of, Thoroughly Modern Millie with Julie Andrews and Carol Channing.

WARHOL: I saw that, I liked it a lot.

MOORE: And there were a couple of other forgettable pictures.

GALLANT: It’s the forgettables that we want to talk about.

MOORE: You’re evil. I guess I’ve done five movies.

BERLIN: What are you doing now?

MOORE: I’m reading a lot of scripts and screenplays, and turning them down. I used to see that in articles about performers, actors and actresses, and I used to think, Oh come on you can’t be reading that many scripts and turning them all down. But truthfully, I’ve read 15 scripts in the last two months and each one of them I have had to say no to because they didn’t measure up to my expectations or what would interest me and challenge me. Also they were not the quality of Ordinary People. So I’m between a rock and a hard place. I miss working. It’s painful though, because I’m a real fish out of water.

GALLANT: It would be more painful if you jumped at something your heart wasn’t in.

MOORE: Of course.

WARHOL: You were in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Where did you learn to sing?

MOORE: I started out as a singer and dancer. I was a chorus girl right out of high school in television. I did a little bit of dancing and studied singing. It’s an area of performing that’s still closest to my heart.

WARHOL: Oh, then you should do a musical.

MOORE: It’s so hard.

WARHOL: It would be great to do a movie musical.

MOORE: It’s such hard work. A movie musical would be fine. I’d like to come back and do a play again too, but it’s going to take me a year to recover from emotional trauma of doing a play.

BERLIN: Do you want to do any television?

MOORE: Not unless television changes. The kinds of shows that seem to work now, the comedy shows, are those which require very little attention. They’re superficial and I like articulate comedy. I don’t know how to do the other, so I won’t consider television until the audience’s taste changes.

BERLIN: TV has gotten so boring that the only thing I watch is the news.

MOORE: I feel the same way. I have to make a few exceptions. There is still MASH, Barney Miller, and there’s a new show that comes from my production company, and I’m not touting it, but it’s just that good, called Hill Street Blues. There are one or two others that are good. But television has such a tough job they’re fighting so many distractions in a room. Kids cry or someone wants to get up and go to the refrigerator to get a Tab and it’s a tiny screen. And I see good work that has not been paid attention to. It’s discouraging. When you do film that’s it, you have a captive audience. When you’re doing a play, you also have a captive audience. It’s hard to think about going back to it. I think what television does best though is coverage of media events.

BERLIN: That calzone looks delicious.

MOORE: My weakness is pizza, any form of carbohydrate. I like junk carbohydrates, I like cheap greasy cheeseburgers, quality french fries.

GALLANT: Which are quality french fries?

MOORE: I went to a place called Max’s Kansas City the other night. They have wonderful french fries that actually have the hint of a taste of potato in them. I went on a punk rock binge on Saturday night. We went to the Mudd Club and TRAX and saw that 12-year-old Chandra.

GALLANT: How was she?

MOORE: Terrific.

WARHOL: We went down to the Rock Lounge and they had these kids there with blue hair, Levi and the Rockettes. They look like young little sons of Superman. But you never see these kids in the daytime. They must just get up at night.

MOORE: What do they do for a living?

WARHOL: This was a group, a really great group. They have a record.

MOORE: I’m doing so many things I’ve never done before.

GALLANT: Mary is going through adolescence. It’s really interesting.

WARHOL: You weren’t a hippie during the sixties?

MOORE: No, I was very conservative during the Sixties. I was very unaware of much of what was going on then. When you’re doing a television series, unless you really pay attention to your life, it doesn’t leave very much time for anything else.

WARHOL: Reruns are my favorite things on TV.

MOORE: Reruns are wonderful because it usually indicates that they had something going for them to begin with and that’s why you’re still looking at them. And in both my shows, The Dick Van Dyke Show and the last one, they were so well written and so good they hold up.

GALLANT: They really do hold up and then they make the transition to a classic art form when they’re in the rerun formula.

MOORE: What’s funny, is in New York, The Mary Tyler Moore Show is on from 2:00 to 3:00 in the morning and you can’t believe the amount people who stop me in the street to say that they watch it every night. I’m stunned.

BERLIN: Mary, you have such a good figure, do you do a lot of exercise?

MOORE: Yes, I dance.

BERLIN: I hate exercise, but I bought a bike last year. I rode on it once.

MOORE: I ride on the sidewalks when I ride a bike. I won’t go into the street unless it’s on a Sunday and the streets are deserted.

BERLIN: Do you ride in the park?

MOORE: I did once and I came very close to being mugged. I went down a very narrow little tree shaded path and I found myself all alone on this path and then I heard a voice from behind saying, hey lady, can I talk to you for a minute? I knew that was trouble. I just peddled as fast as my little legs could do it. So you learn what to do not to do.

GALLANT: I’d like to talk about adolescence.

MOORE: Adolescence has such a negative connotation and it shouldn’t. It’s experimentation, it’s being unsure, no preconceived notions.

WARHOL: But it also is the way you look, too. Some people look 40 when they’re 40. People look the way they’re supposed to look at any age. Gloria Swanson looks 40.

MOORE: She really is phenomenal.

WARHOL: Looking younger and being younger is the adolescence idea.

MOORE: For me, the adolescence I’m talking about is attitude and point of view.

WARHOL: But that’s the attitude you get, too, because you have the look to go with it. You could never be an adolescent if you don’t look like one.

MOORE: Maybe in adopting an adolescent attitude you then take on the look of a young person.

WARHOL: Look at those cops.

MOORE: Ooh, wow.

WARHOL: People in uniform always look so great. If he had a suit on he wouldn’t be great.

MOORE: It’s the garb of power, the guns strapped to the hip that accentuates it.

BERLIN: What’s a normal day for you in New York?

MOORE: Depending on how late I’ve been out the night before I get up anywhere from 9:00 in the morning to 10:30 and on those days when I get up at 9:00 I go over and take a dance class. I come back and then maybe I’ll have a luncheon meeting with someone to discuss a script or talk with a writer or whatever. I come back and will probably have a session with a tutor that I’ve been working with in political science. It’s a new interest of mine. It’s far too early for me to talk in specifics about what I’m doing. It’s just an interest I’m pursuing. Then three times a week I’ll have a session with my analyst, come back and answer mail and return phone calls and then have dinner with friends.

BERLIN: Do you like to shop?

MOORE: No, I hate shopping.

BERLIN: Where do you buy your clothes?

MOORE: I like boutiques, I like Emanuel Ungaro. I like Adolfo, I like Oscar de la Renta.

BERLIN: What are you going to wear to the Academy Awards?

MOORE: I don’t know yet.

BERLIN: Do you go to the Academy Awards every year?

MOORE: No, I prefer to sit home and watch it on TV. I think you get a much better view and you have friends there who you can comment on it with. I went once before, I was a presenter. It was really boring.

BERLIN: What do you collect?

MOORE: I have some snuff boxes, but it’s not a major collection. I collect books and I also have a modest collection of brass English hooks. That’s about it, I’m not really a collector.

WARHOL: It’s great not to be a collector.

BERLIN: Are you going to decorate your apartment yourself?

MOORE: No, I’ll have some help. I don’t have the time or the inclination to be as imaginative as a decorator can be. I’ll work with one on it, imposing to as large an extent as I can my own taste.

BERLIN: When are you moving in?

MOORE: As soon as the construction work is finished which will probably be ten months to a year. I want to do over all the bathrooms and kitchen. I have to re-arrange closets.

GALLANT: It’s such a beautiful apartment.

WARHOL: I hate things to be redone, I would just move right in. I like the old look.

MOORE: You have more courage than I do. I need more closet space and as a result things are going to have to be moved around.

WARHOL: Make two rooms into a closet.

MOORE: There aren’t that many rooms. It’s a small apartment. It has a large living room, large dining room. It has an average-sized bedroom and a guest room and that’s it. And then there are the existing New York closets.

WARHOL: Polly Bergen is really great. She just turned one room into a closet.

MOORE: I would do that if I had the extra room.

WARHOL: I think bathrooms are great. They’re better than a living room. Cut out the living room and make it a closet.

MOORE: Have a party and invite everyone into my bathroom.

GALLANT: What are three things you want to do and have never done?

MOORE: One of them I’m going to do this week and that’s go skiing.

WARHOL: You’ve got million dollar legs, you’ve got to think about them.

GALLANT: Only good skiers get hurt.

MOORE: [Robert] Redford is a really good skier and was constantly breaking his face.

BERLIN: What was it like working with Redford?

MOORE: It was one of the best experiences of my life. He is my good dear friend and will be forever. The work experience was so professional. He knew what he wanted going in and yet he was artistically open to everybody else’s suggestion. He would constantly pick your brain and say what do you think, give me your feeling. His demeanor on the set was that of a guy who was doing his tenth picture, not his first. He was kind and considerate and confidence instilling because he didn’t ever show any of the panic that he swears he was feeling at the time. It’s a project that was very close to him from its inception. When he first read the galleys five years before that, he knew he wanted to make the movie. He was very careful with it. He’s a wonderful wonderful person. I can’t think of two other things that I’ve always wanted to do, I mean things that you can talk about in print. I would like to go out of a plane on a parachute someday. I don’t think it would ever become an ongoing hobby of mine.

GALLANT: Don’t you want to make an album?

MOORE: No.

GALLANT: Do you want to write a book?

MOORE: No. I wish that I could write though. I think that’s a wonderful outlet for an artist. You are ultimately in control. Your fate is not determined by outside influences. You can write wherever you are. I don’t think I have the talent.

WARHOL: Just carry a tape everywhere you go and a telephone plug.

MOORE: The thing is I never want to be an observer, it’s only in retrospect that I wish I had observed. I’m sort of doing a lot of the things now that I never thought I would and that I wished I had done a year or so ago.

GALLANT: What things?

MOORE: Living on my own and developing friends of my own, pursuing my own interests which are not connected with somebody else.

BERLIN: Do you find it difficult?

MOORE: Sometimes. It’s difficult and it’s frightening, but ultimately throughout it all it’s exciting and it feels right.

BERLIN: You don’t seem like the kind of person who needs to go to an analyst.

MOORE: I go to an analyst not because I need to but because I choose to and maybe that’s the difference. I don’t think I have any huge neurosis, but I have questions for which I seek if not answers at least a guidance toward the answers.

WARHOL: Doesn’t a friend tell you the answer?

MOORE: No, because each best friend will have a different point of view.

WARHOL: So will the doctor.

MOORE: No. I think they can be a little more objective than a best friend can be.

WARHOL: Only because you have to get to like the doctor and know that that doctor is your best friend.

MOORE: I don’t want him to be my best friend. The doctor that I’m going to doesn’t give me any answers.

BERLIN: I quit my analyst because he didn’t give me any answers.

MOORE: A friend will give you immediate feedback and that will be that friend’s opinion. An analyst often remains quiet and you hear what you’ve said and you gain your own insight.

WARHOL: You can talk to the cabdriver. He’ll tell you anything.

MOORE: I don’t want anyone to tell me something.

BERLIN: Andy will listen, he’s the best analyst.

MOORE: Then, too, you don’t always want to burden your friends.

BERLIN: How did you and Ara meet?

GALLANT: We have mutual friends. I like Mary’s position in life now. She’s actually building, constructing, and designing her own life according to her own whim. It is the ultimate luxury.

MOORE: It sounds wonderful. Well, if you have the ability to do that and I am blessed with that ability, it’s a crime if you don’t.

WARHOL: I watch you on TV all the time and now that it’s for real it’s getting scary.

BERLIN: TV does that. It’s much different than having fans in the movies.

MOORE: Oh, very much so.

BERLIN: You begin to really think the characters on TV are your friends.

WARHOL: I miss Rhoda, can’t you put her back on? Why did she go off?

MOORE: The audience dwindled.

WARHOL: Not me, I was watching Rhoda.

MOORE: It did very well while she and Joe were married. When they got a divorce and Rhoda struck out on her own that’s about the time that the viewer dropped it.

WARHOL: Can’t you get her married again?

MOORE: I don’t think she would like to go back to television anymore than I would like to.

BERLIN: It was funny that you never got married on your show.

MOORE: We felt that would have been compromising what the show was about. Her life focus was on things other than a permanent sexual romantic attachment, which in a way parallels my views these days. I’ve had that and now I’m about other things. To have compromised that on the show would have been another series altogether.

CASTELLOTTI: Wouldn’t you like to take that home?

[Leaving John’s]

MOORE: I certainly wouldn’t. I have to fit into ski clothes on Wednesday.

WARHOL: Can l take your picture with all the cops?

MOORE: Sure. It was so funny, the other night I was surrounded at a restaurant by the Mafia, now I’m surrounded by the cops.

GALLANT: With your new approach to life and your freedom do you feel that in your personal relationships with men and women you have to be leery or fearful?

MOORE: I don’t think I have to be fearful of it, but I certainly think I have to be aware of the potential inherent traps that I might fall into based on past performance which was to be always exclusively tied to one person.

BERLIN: Do you want to get married again?

MOORE: No. I think marriage, in its loosest sense, is people committing to each other saying I love you and I like being with you and that is wonderful. I don’t see the need to formalize it unless you plan to have children and you want the fair distribution of assets. I also don’t think you should ever expect forever in anything, in either platonic friendships or sexual friendships.

GALLANT: The most sadistic thing that somebody could say to me is I’ll love you forever.

MOORE: I wouldn’t want to enter into a relationship in which there was this inhibiting factor that said it can never be forever.

BERLIN: Do you have a boyfriend?

MOORE: No.

BERLIN: Were you going out with Warren Beatty?

MOORE: Warren and I are friends. I don’t answer any questions about my personal relationships. I spent most of my life while I was working married so any of the personal questions were fairly easy to respond to because there was never any question of my privacy, his privacy; that was no book, we were married. There were certain private areas. But now that I’m a single woman and I do have relationships with people from time to time, I find I can’t respond to questions about those personal relationships.

BERLIN: You and your husband, Grant Tinker, are still very close.

MOORE: Oh, yes.

WARHOL: You’re still going on together with your business?

MOORE: Oh, sure. Our company’s going to do a movie here in New York. I’m not involved in it.

WARHOL: But it’s still your company isn’t it?

MOORE: Grant’s and mine and two other people.

WARHOL: How did that happen? That’s a really hard thing to do.

MOORE: Well, it really started with Grant. CBS asked me to do a series and obviously we needed somebody to produce the series, so Grant came into the company from Twentieth Century Fox and said, alright, we’ll make this show and it was successful and then came Rhoda, Phyllis, and the rest of them. It started with his expertise because he’d been at NBC and he’d been at Universal and was thoroughly knowledgeable in that area which I have not been. I would like to be more involved as time goes on.

WARHOL: Could you be?

MOORE: Oh, sure. In the sense that I would surround myself with people who know what they’re doing.

WARHOL: Are you President, Vice President?

MOORE: I’m Chairman of the Board.

WARHOL: Do you have a studio?

MOORE: We rent space in Studio City and Hollywood.

WARHOL: Can’t you get Mary, Phyllis, and Rhoda back together again?

MOORE: Why would I want to do that? It wouldn’t be good for the audience.

WARHOL: I watch The Brady Bunch and it’s good for the audience and it’s so much fun.

BERLIN: I don’t think it would work today.

MOORE: I’d be playing the same character that I did for seven years. It would be like asking you to paint the same Campbell Soup can again.

WARHOL: But I do. It’s great. Everybody does the same thing over and over again. I like to do the same thing every day. Well, I’m different. I like to paint the same painting. If I had my way I’d paint Campbell Soup cans every day. It’s just so easy and you don’t have to think. It’s just too hard to think.

MOORE: What areas do you do your thinking in? You’re obviously a thinking person.

WARHOL: No. I just do the same thing every day.

MOORE: Don’t you ever get bored?

WARHOL: No.

MOORE: You know what we need now, is a hot fudge sundae.

WARHOL: We can get it at Serendipity.

MOORE: Oh, Serendipity, I have been spotted there from time to time.

GALLANT: We can go there now for dessert.

MOORE: With a side of salad?

BERLIN: Could you eat salad now?

MOORE: Yes, I could.

WARHOL: Isn’t there a better place for salad?

MOORE: Inside this tiny body is a truckdriver.

WARHOL: Mary, where’s your voice from?

MOORE: Brooklyn.

WARHOL: You’re from Brooklyn?

MOORE: Yes.

WARHOL: No you’re not.

MOORE: I’m born of impoverished nobility, but yes, from Brooklyn. I was born and grew up for two years at 491 Ocean Parkway. I went to St. Rose of Lima Grammar School. And then we moved to Flushing. Lived there for a couple of years and back to Brooklyn. And when I was eight we moved to California. So I really consider myself a Californian, but I have those great comedic roots in Brooklyn.

BERLIN: I love your crow’s feet, I think they’re absolutely marvelous.

MOORE: Oh, shut up.

BERLIN: It’s a compliment. They make your eyes look so big. I’ve always wanted them.

MOORE: You want them? Here, take them.

BERLIN: I think they add such character to a face.

WARHOL: I disagree. Do you know Frank Sinatra?

MOORE: No, he lives on my floor at the Waldorf.

WARHOL: I think he’s so good. I almost became a Republican. I go to all these thousand dollar a plate dinners because he would sing at them. He is just terrific.

MOORE: I saw him perform in person once and it was mesmerizing. I keep hoping run into him in the hall so I can spend some time with him because I really do love his work.

WARHOL: All the cops are singing. Gee, maybe they could ask you some questions. Would you do that?

MOORE: Sure.

WARHOL: Would you interview Mary Tyler Moore for us?

COP: Anytime. Would you like to ride my horse tonight?

MOORE: Oh, could I? I’d love to ride your horse. I just started horseback riding. Do I really get to ride a horse?

COP: If you want to.

MOORE: Are you all on horseback?

COP: Yes.

MOORE: Where do you have them tied up?

COP: They’re hidden.

MOORE: Are they English or Western saddle?

COP: Western.

MOORE: I started riding in Central Park. Is that a bad idea?

BERLIN: I’ve been warned off it.

COP: Central Park is beautiful because they’ve got about seven miles of bridle path, but the problem is it’s changed. Somebody is liable to drop a rock on you.

MOORE: I heard about that.

COP: You don’t want to go there. You really don’t.

MOORE: We’ll meet here three times a week and ride on your horse.

COP: When you’re in LA and you’re going down the freeway and you get stuck, I want you to say you’re a very good friend of Nick Williams of the New York City Police Department and here’s his card.

MOORE: Oh great, thank you. But I’m a New York resident now. I have a stepson who is a cop in Los Angeles.

COP: We were invited to the Inauguration by Reagan to ride in the unit.

MOORE: I don’t think there’s anything quite as dashing as a cop on horseback. To me it’s wonderful.

COP: It’s great. It’s becoming more and more popular.

MOORE: What happens if you’re on horseback and there’s an emergency, there’s somebody mugging somebody, and you’ve got to jump off the horse and save this person, what happens to the horse? Do you ride two by two?

COP: No problem. We generally ride alone. You get used to it. You deal with it, no problem. Sometimes you just hand it to some passerby. It always works out. We’re down here all the time. Greenwich Village and Times Square. I love Times Square. And the Village is great once you get these streets down. The people in the Village are very nice people. I’m in the Village ten years. We had a stable on 55th and Tenth but that closed.

MOORE: Do you ever get a chance to open the horse up, to really canter?

COP: Sure. If you have to get somewhere in a hurry you canter. I rode several times with Jackie Onassis and the secret service man was running along.

MOORE: Well, we have a choice. We can either ride horses or go get a hot fudge sundae. I want to have a hot fudge sundae on a horse.

COP: Vince Sardi is an auxiliary mounted cop. He’s a friend of ours. He rides with us. He’s been influential in trying to get us a stable located in midtown on 42nd and Eleventh Avenue. That’s what we need. He donated a horse to us. We named him Sardi. The theater district has been helping us out tremendously. They donated a horse, the St. James. And they donated another horse, the Shubert. “21” donated a horse. The garment district donated two horses, Markup and Markdown.

MOORE: How much does a horse cost?

COP: Anywhere from $500 to $5000. The New York Times donated a horse, Front Page.

MOORE: Someday I’ll donate a horse and you can call her Mare. Well, we’re off to get hot fudge sundaes. It was really nice meeting you. Thank you so much.

COP: It was a pleasure.

BERLIN: It’s pouring rain.

FRANK SINATRA [on the jukebox]: “These vagabond shoes.”

CASTELLOTTI: Good seeing you, Andy. My pleasure.

WARHOL: We’ll be back.

MOORE: We have a car.

[In limousine en route to Serendipity]

WARHOL: They were cute.

GALLANT: Who said New York isn’t friendly?

WARHOL: Isn’t New York great?

MOORE: It is the most friendly place. In fact, it’s getting too friendly in certain respects. The Information Operators who give you the number say, “Have a nice day,” and cause you to forget the number they have just given you.

WARHOL: Oh, I know.

MOORE: I love the rain. What’s nice about the rain is you don’t feel you have to live up to anything. Everything around you is so grey and wet and damp and dreary that you don’t feel you have to smile and percolate as you do on a sunny spring day. I can hardly wait to get to Serendipity and have a bowl of coffee. That’s the way they serve it, in a stemmed bowl.

WARHOL: Coffee never used to keep me up at night, now it does.

MOORE: It’s just the opposite for me. I can have expresso, cappuccino at 1:00 and I sleep just fine.

BERLIN: Because I’m almost fasting, have so much energy. I wake up at 5:00 every morning. I feel like I’m on speed. There is a high to fasting.

MOORE: I’ve never tried it. I wonder what it would be for a diabetic, which I am. I wonder if you can go on a fast?

BERLIN: Do you take insulin?

MOORE: Yes.

WARHOL: How do you take that, by pills?

MOORE: No, by injection. There’s no cure for diabetes, there’s only control by insulin.

BERLIN: You’re having a sundae tonight do you have to take more insulin?

MOORE: Yes. When I go home I’ll take a little extra. Eating sundaes is something you can’t do every night.

WARHOL: But I thought you can take pills now.

MOORE: It depends on what kind of diabetes you have. There’s maturity onset diabetes which means that people usually are not metabolizing sugar because they’re eating too much sugar and so if they then regulate their intake of carbohydrates they can control it with pills and exercise. Then there is what they call juvenile diabetes, which is what I have, and that means that the pancreas is producing no insulin. It’s not just not producing enough, but none so you have to inject insulin.

BERLIN: How long have you had it?

MOORE: About 15 years.

WARHOL: God I just started buying sun dried papaya, it’s so good. They come in big orange strips.

MOORE: That’s concentrated sugar and it would be the worst thing in the world for diabetic or for anyone who is allergic to sugar to eat.

[At Serendipity]

MOORE: Now I’m counting on you, Ara.

GALLANT: We’re going to split whatever it is. You know the size of those things.

BERLIN: I’d never let anybody share dessert with me or even have a taste.

MOORE [to waiter]: I’ll have the dietetic hot fudge sundae. Vanilla ice cream with hot fudge, whipped cream and nuts.

WARHOL: Oh, can I have half a sundae?

MOORE: I want the half size, too. I didn’t realize you could do that. And could I have Sanka with Sweet’N Low?

BERLIN: Mary, what are your favorite restaurants in New York?

MOORE: I like Le Relais.

WARHOL: Where do you sit, in the back?

MOORE: You know the partition that separates the bar from the restaurant with the milk glass? That’s my favorite table. Well, now, John’s for pizza. I like Mr. Chow’s.

WARHOL: The ice cream here is great.

MOORE: Now it’s over for me and I don feel any better or any happier for having eaten that.

BERLIN: I don’t call that eating a sundae. You have one taste. I would have finished two by now. So you’ve given up your house completely?

MOORE: I’m going to sell it.

WARHOL: Can’t you just keep it for investment?

MOORE: No.

WARHOL: Is it in Beverly Hills?

MOORE: Bel Air. It’s a lot to keep it going

BERLIN: Do you want a country house here?

MOORE: I think I will eventually. I’m going to look at places when I get back from skiing to rent for the summer.

BERLIN: Where do you want to go?

MOORE: I don’t know. I want a place right on the water. I’m going to be looking as far east as Quogue and as far south Fire Island. Maybe this time next year I’ll buy a place.

WARHOL: Montauk is really beautiful.

MOORE: I was there for five days last year. I stayed at Guerney’s Inn.

WARHOL: I have a house right near there. I rent it to Halston. Dick Cavett is right next door.

MOORE: I talked to Dick the other day and he was trying to lure me there.

WARHOL: You can have a lot of privacy there. But Easthampton and Southampton are so much fun.

MOORE: One thing I know I don’t want to do is to go out there with a lot of cocktail frocks.

BERLIN: Nobody bothers you out there. Most people I know out there never leave their houses.

MOORE: That’s the life I want to lead.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1981 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.