lit

Raven Leilani Wants to Write About Sex in a Way “That’s Ugly”

———

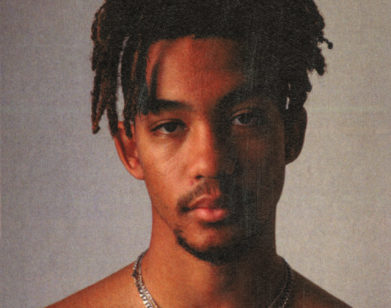

In the first few pages of Raven Leilani’s debut novel Luster, Edie, a 23-year-old artist caught in the quicksand of student debt and dead-end administrative work, meets an online lover at an amusement park. The lopsided power dynamic of their interracial, May-September romance becomes particularly glaring when set against the park’s overly plastic, juvenile locale. “He wants me to be myself like a leopard might be herself in a city zoo,” Edie remarks. “Inert, waiting to be fed.” The protagonist’s unflinching, hand-to-flame nature parallels the 29-year-old writer’s own experience with the constant self-advocacy and tolerance required to be a young, Black woman in contemporary America. “There are a lot of dreams deferred here,” says the Brooklyn-based Leilani, who spent five years after college working a number of low-paying jobs: as an archivist for the Department of Defense, a staffer at a scientific journal, and a Postmates delivery person—all while writing at night and logging a spreadsheet of rejections from literary journals. (Leilani is the author’s middle name; she decided to create a pen name to maintain “a totally antiseptic professional avatar” for her many day jobs.)

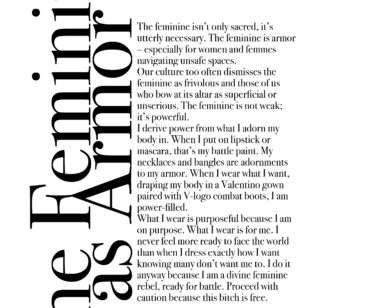

Born in the Bronx but raised in a small town near Albany, New York, Leilani found her artistic calling early on—first in painting, then in writing. Her “big, weird family,” as she calls them, were encouraging, particularly her mother who worked as a hairstylist, a seamstress, and, later in life, a mortuary technician at the Department of Veterans Affairs. It was in the first year of her MFA program at NYU that she began writing Luster, which has already caused a stir for its frank, tactile, sometimes-messy depictions of sex. “There are parts in this book that are teetering on transgressive,” she says. “But I really wanted to show what it looks like when a Black woman, who is already experiencing the subjugation of her body in the public realm, then chooses to invite that in privately. It’s tricky to articulate—but there is a freedom in that surrender.” Leilani says her goal is to write about sex in a way “that’s ugly, and by ugly I mean un-curated.” Her language is especially freeing for the female reader: Edie’s vocabulary for her body and all its functions ranges from the clinical to the pornographic, along a spectrum of words usually saved for the way men describe women, and for women to wince at. “There is a certain kind of shamelessness that I want to embrace in writing,” says Leilani. “It’s for us to claim our bodies and talk about them. It’s not sordid—in fact, it’s ordinary.”