Ramona Ausubel’s Tall Tale

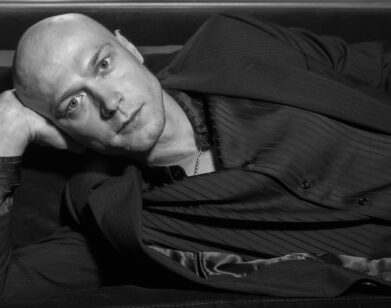

ABOVE: RAMONA AUSUBEL. PHOTO COURTESY OF TWIN LENS IMAGES

Writer Ramona Ausubel defies the harnesses of history in her debut novel, No One is Here Except All of Us. In 1939, an isolated Jewish village in Romania has a fantastical solution to the brutality of World War II: they pretend it doesn’t exist. Characters shuffle jobs, spouses, even children; they restart their lives from day one, forgetting everything that came before. It’s a nearly unbelievable premise, but the reality of the war eventually trespasses upon the village’s willed ignorance and defeats their attempt at a fresh start. Human lives are not so easily altered—and old stories are not so easily forgotten. Ausubel follows her eleven-year-old narrator into adulthood, when she flees from her reclusive village to the real world. No One is Here Except All of Us is both a tale rooted in history and a dreamlike departure from reality. With lyrical prose and a poet’s sensitivity, Ausubel weaves a story that is largely, itself, about stories.

We spoke with Ausubel about the fables that contain more truth than history books, her five-foot tall grandmother, nostalgia for an imaginary world, and her drive to squeeze strangeness and beauty onto every page.

CLARE STEIN: Your book is focused on storytelling. Since this will be published online, what do you think is the importance of storytelling in the digital age?

RAMONA AUSUBEL: I think the importance of storytelling isn’t that different now than it ever was. I think that we are all trying to fold the past into the present and figure out where we stand and pass things along. We’re doing things in a different way than we used to, but it’s the same meaning for us, I think.

STEIN: I know you began writing No One is Here Except All of Us because of your grandmother’s stories. Can you tell me more about them?

AUSUBEL: She’s a great storyteller—she’s under five feet tall now, but she used to be a whole five feet—she’s just funny and amazing and she remembers absolutely everything that’s ever happened in the world. I remember from being a little kid all the way up to being older, sitting there, completely riveted. These tales seemed impossible to me; they were from another world completely. It occurred to me when I was about 23 that these were things that happened to people who were related to me. That was really fascinating, and I felt like I needed to understand them better and understand how they could have possibly been true. That’s how I started writing about it. There was no way to go back to Eastern Europe in 1920 and talk to my great-grandmother, but I could make a version of her in my life and write about it and get to know her that way.

STEIN: At what point did you move from trying to capture your grandmother’s stories as a part of history to fictionalizing and straying away from the bare-bones truth?

AUSUBEL: When I first started writing, I was really trying to tell the stories the way she told them, and they were just not nearly as good as her versions of them. I was failing at something that she was very good at. I gave up on the project completely. About two years later, I came back to it and I realized the only way to fill the whole world in was to let go of the facts and anything that belonged to somebody else. And I took it over as my own world. I didn’t open any of my notes or listen to my interviews; I opened the computer and started inventing things from what I remembered from the stories. So the feelings of them carried over rather than the details.

STEIN: What was the most surprising part of writing without notes?

AUSUBEL: It was really surprising how much it really did feel like I was getting to know my relatives. How could I possibly know who they were? But somehow I did. And there was a feeling that they were there with me and we were inventing this world together, and I was getting to the truth even though I was writing fiction.

STEIN: Are you influenced by magic realism?

AUSUBEL: Definitely, yes, I would say I am. I love stories that go someplace that is almost like the world we know, but is one degree different.

STEIN: The novel is also motivated by some urge to capture the past—how did history and World War II influence your writing?

AUSUBEL: I think I am less influenced by that. I like books that take place in interesting places and times, and sometimes those times are far away, but mostly I care about the story and characters. It actually surprised me that I was writing historical fiction. I’m not a researcher. It’s not something that I’m incredibly good at. That part was challenging for me. After I had the original story down, I had to go back and make sure I was not completely wrong about all of the history. That part came a little less easily.

STEIN: In writing this book so focused on village life, do you ever wish you lived in this isolated place where there was the butcher, the saddle-maker, the cobbler… Do you ever have a strange sense of nostalgia for the world you created?

AUSUBEL: I do, sort of. I know what you mean. There’s something sweet about a world that is so defined, where everyone knows exactly what their role is and everyone works together, and it’s completely contained within itself. I did grow up in a small town and there was a tiny sense of that—not that specific—but it did feel like that family was the family that always did that one thing, and it carried on that way. So, I would say yes.

STEIN: One of the main characters is an 11-year-old girl. What drew you to that age?

AUSUBEL: My great-grandmother was adopted by her aunt and uncle when she was a little bit younger than Lena—the character based on her in the book. I started with that story. That was the first of the family stories that felt really important to me. There’s something about that age where you’re waking up to the world anyway, and then to have a huge transition, to be in a different household all of a sudden. You’re trying to understand your new family, your new role, and what it means to be passed on and also how the world works around you in general and who you are. That felt like very rich ground to begin with.

STEIN: Within the first pages of the novel, a strange woman enters the life of this village and sort of spills the beans about what’s happening outside their village life. Can you tell me more about this character—how you came upon her and how you shaped her?

AUSUBEL: At the very beginning of the book, there’s a bomb, an explosion nearby, and a huge rainstorm at the same time. After the rain has finally stopped, the villagers go down to the river and unearth this stranger who is alive and has come out of the river. She is the person who allows them to believe that it could be possible to start the world over, which is the next thing that they do. I felt there needed to be that mysterious outsider who comes to town—so many great books begin with that stranger coming to town—there has to be something that comes from the outside that allows you to make that leap, that you are going to be able to do that crazy thing that you are talking about doing. She didn’t actually come into the plot in the first few drafts, and it was much harder without her. It felt like why is today different from all other days, why would they believe that something like this could happen? I needed her to be this figure to absorb all of their beliefs. She doesn’t necessarily believe it herself, but she realizes that she is the one to hold it for everybody else.

STEIN: That stranger arriving to town is such a major trope of stories from the beginning of time. So, does your novel mirror the very traditional roots of storytelling in other ways as well?

AUSUBEL: I think it does. I don’t know if it structurally does, but there are a lot of themes about stories that get told and told again in the book, and stories that get lost and told a new way in a new generation.

STEIN: Your writing style is very lyrical and poetic. Have you ever written poetry?

AUSUBEL: I have! I started writing poetry, and didn’t actually write prose until this book. I studied poetry in college and have written poetry really seriously for about 10 years before I wrote anything longer than two pages. Then I started this. I learned a lot. I love stories but I adore language, so that is what I always come back to.

STEIN: And how was that transition from poetry to fiction?

AUSUBEL: Hard.

STEIN: I imagine!

AUSUBEL: Very different. It was hard to go from meeting fifteen perfect words to having this expanse of hundreds of pages that felt, at first, like no way this is completely impossible I will never be able to do this. Slowly, page by page… the first draft I wrote very quickly. I needed to get everything down. The thing that kept me alive, that I came back to everyday, was the words. I needed to make pages with language that seemed beautiful or strange or whatever it was. That was the fire that kept the whole thing alive.

STEIN: And you were guided by the stories of your grandmother, of course.

AUSUBEL: Exactly, yes. I had those stories in the background. They were my stepping-stones, and I wrote from one to the next.

RAMONA AUSUBEL’S NO ONE IS HERE EXCEPT ALL OF US IS AVAILABLE NOW. A FINALIST FOR THE PUSHCART PRIZE, AUSUBEL’S WORK HAS BEEN INCLUDED IN THE NEW YORKER, THE BEST AMERICAN SHORT STORIES, AND THE BEST AMERICAN NON-REQUIRED READING.