LIT

R.O. Kwon and Alexander Chee on How Kink Can Liberate Us

R.O Kwon. Photo by Smeeta Mahanti.

When R.O. Kwon published her story “Safeword” in a 2017 issue of Playboy, she was anxious about how readers were going to react. In it, a securely vanilla husband takes his kinky wife to see a dominatrix by the name of Mistress Ava. It was, by far, the most explicit piece of fiction Kwon had ever written. Being a woman on the internet, she says, she tempered herself to what were sure to be lewd and invasive responses to the piece. However, she was surprised to receive gracious notes from readers. Her story, about a woman freely pursuing her untapped desires, made them feel less alone.

Around that time, Kwon had read Whip Smart, Melissa Febos’s memoir about her own transformation from college student to dominatrix, and Garth Greenwell’s story “Gospodar,” in which an S&M encounter leads to trauma and catharsis. At her MacDowell residency, Kwon thought, what if there was a book where works of fiction that engaged with kink in new and meaningful ways could live together? She got in touch with Greenwell, whom she had interviewed upon the release of his first book What Belongs to You, and pitched her idea. To Kwon’s great joy, and in the spirit of the project’s playful and risqué subject, Greenwell responded, “I don’t really know what you’re asking, but I think, yes.”

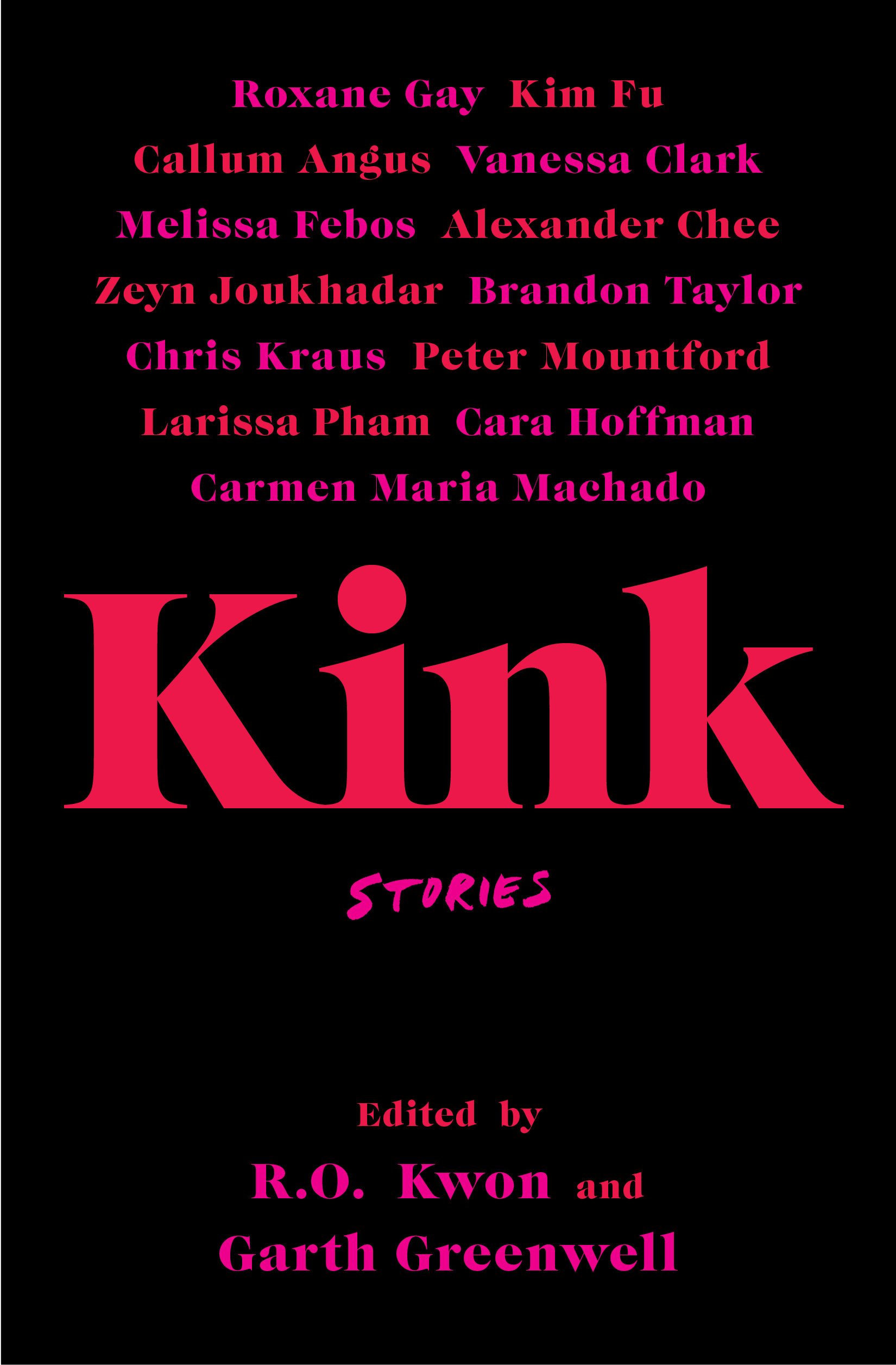

Kink, co-edited by Kwon and Greenwell (and out from Simon & Schuster today) anthologizes fifteen arresting portraits of pleasure, pain, and power. The book gathers original and previously published stories from writers who, each in their own work, push the boundaries of literary fiction and invite readers into the lush and liberating interiors of human desire. Among the contributors are Alexander Chee, Roxane Gay, Chris Kraus, Carmen Maria Machado, and Brandon Taylor. I caught up with R.O. Kwon and Alexander Chee to talk about Kink’s exciting potential for transforming literature and our disorienting culture of hypervisibility and isolation.

———

MICHAEL LONDRES: Hello to you both! I’m so excited to talk to you about this anthology.

R.O. KWON: Hi.

ALEXANDER CHEE: Hi. I have to apologize because my lunch just arrived, so I’ll be eating.

KWON: Ah, I have a bowl of Wonton soup right next to me.

LONDRES: I should have planned this better. We could have all eaten together. How is everyone doing? How is your almost one year in quarantine?

KWON: I’ve been really relatively lucky. One of the good things about this past year for me has been somehow feeling more strongly connected to my community than I ever have. With so many friends, I feel closer, even, than before the pandemic, and that has been a great blessing in this terrible time.

CHEE: The objective facts of my situation have been pretty decent in many ways, but it feels weird to now feel like I am an elite, because I still have a job, healthcare, and a home. That’s creepy in the United States. My husband had COVID early on. I nursed him through it. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. When quarantine began, I was working at healing some long-standing problems with my knees. I realized I wasn’t strong enough to get him down the stairs by myself. That was a really dark feeling. So I upped the physical therapy and now I could, if I had to, carry him out of the house. That’s a strange barometer to have for my sense of safety, but that’s where we are.

LONDRES: What has helped you get through the past year?

KWON: I have a lot of accountability systems running right now. I think I might have five or six and two of them have to do with writing, where we tell each other how much we hope to write that week. Maybe two months into the pandemic, I was joking that I can’t keep drinking as though it’s a disaster, even if it is a disaster. My first motivation was that I needed to outlive these fuckers. I became more involved in electoral work. I’ve had a lot of hesitations about it, and I wasn’t especially excited about Biden as a candidate, as a lot of people weren’t, but after RBG died, I was so grief stricken. It wasn’t just what it meant for the country, it was also about this one woman having tried so hard to stay alive, and not having been able to at the end. That was too much. Sorry, I’m tearing up a little.

LONDRES: It was an immense weight resting on a single person.

KWON: Yeah. There was this wonderful moment—by wonderful I mean terrible too—where all that sorrow gathered itself up and turned into rage. Suddenly I had energy. The best answer to feelings of hopelessness and despair is to act as though I have hope. There’s no way to work toward a better future without believing that it could be possible. Those have been the things that have sustained me, I’d say, and friends like Alex, who, the night RBG died, did such a lovely thing. People on social media were just losing it, and Alex DMed, and said, “How are you doing, love?” He was like, “Today, I’m checking in on friends. Tomorrow, I’m going to throw myself into the fight.” Ah, Alex’s wisdom, man. That was so great, Alex.

CHEE: Thank you. I remember that night I was very aware that my women friends would probably need checking in on. One of the first things I did when the pandemic began was checking in more with my Asian-American friends and community, because of the attacks on us. I also started doing this thing. People made fun of me, but I don’t really give a shit. I was growing vegetables out of scraps from the kitchen, and I developed what I called “carrot beach”. My mother had given me this glass cocktail snacks divider. At an ordinary party you might put Chex mix, peanuts, and wasabi peas. Instead, I had carrot tops, bok choy, and scallions. In the middle of winter, and as the death toll started to go up, it helped to wake up and see things grow a little bit every day. When spring came, we planted a genuine garden, and I was able to plant a number of those plants that I had shepherded through the winter. Whether or not I ever ate anything, it really gave me this moment of pure connection to life in a way that so much of the landscape wasn’t offering me.

LONDRES: Let’s get to the big question: what is kink?

KWON: When Garth and I started thinking about our vision for the anthology we agreed that it was important that we not define kink. When we emailed people to ask if they may want to write for us, we said, “Would you be interested in writing a story that engages with kink as you understand it?” The last thing we wanted to do was play any sort of gate keeping. The problem is that the words “nonnormative” and “nontraditional” are often used to describe kink. But what is normal? The best definition, the only definition that makes sense to me is, kink is open to a wider variety of possibilities of what sex can be. It doesn’t fully satisfy me yet, but…

CHEE: Hm. I like it though.

KWON: I should mention, Garth is the one who said that first. I should credit him.

CHEE: Within a culture that still largely supports a kind of compulsory heterosexuality, the state advantages certain kinds of families over others, and seeks to define our relationships to each other in those ways. I think of queerness, for example, as a revolution that begins around your awareness of how your desires don’t fit into those categories. But then saying that it’s about varieties of pleasure makes it sound like some sort of sexual Etsy. Exploration of kink, to my mind, is about exploration of the self in relationship to things that are connected to desire and pleasure that might not technically be codified as sex, per se, but that can reshape you, or your relationships, or your sense of where you fit into the larger world.

Alexander Chee. Photo by M. Sharkey.

LONDRES: What is the state of sex in contemporary fiction? How would you describe the literary culture that the anthology is responding to?

KWON: I, from the start, was interested in pushing back against what I’ve seen to be the dominant narratives of what kink is. The example I always give is that, in books, TV, and movies, when a character is a serial killer, the game I play is, how long before we find out that they are also kinky? The other popular depiction of kink is emotionally stunted billionaires. And that’s about it, serial killers and billionaires. Some of the most unappealing people you could imagine. I feel as though kink jumped quite fast from being very taboo, and not something that was talked about, to being a joke. With this book, I was interested in going back to the part where it’s about people, about human beings.

CHEE: I think for myself, as a gay writer who came up through the nineties and the oughts, and whose first novel was tagged as being sexually explicit in ways that were considered groundbreaking at the time—I don’t know if you guys remember this, but Amazon decided that a whole category of books were pornographic and disappeared them from searches.

KWON: Oh my gosh.

CHEE: Yeah, my first book was one of those books. I got to experience, in a kind of literal way, that sort of techno prudery. It was very clear to me that there was a way that I could be honest about gay men’s lives in a pornographic magazine, for example, that I couldn’t in a literary magazine. And so, the question became, do I want to write something that’s honest, and then have it essentially be shunted into this niche, or do I want to publish something that is literary, quote, unquote, which meant the sort of tasteful, fade to black whenever sex might appear?

LONDRES: Or pan to billowing curtains.

CHEE: Right. My story in the anthology is one that I wrote at a time when I was really trying to push at those limits inside of myself. It was written just after I published my first novel, and there was still this way that I was like, what is it like to write “cock”, to use the language of porn in a story? It was funny to see the review of Kink in The New Yorker, where the critic, who I like quite a bit, Katy Waldman, called my story “unapologetically porny”. I was like, “Yes, I am not apologizing for anything.” But also, it strikes me as a part of, to invoke Garth, how the culture’s fear of bad taste is something that can really trip you up as a writer. I am often encouraging my students to err on the side of excess, to rid themselves of this idea of what is in good taste as they approach describing things as they are. That includes desire, and sex, and kink.

LONDRES: Pornography, romance, literary fiction—where do the boundaries lie these days? Where do the stories in this anthology feel most at home?

KWON: I know they’re useful, but I don’t find any of these labels satisfying. That said, I do also know that, where I feel most alive is in fiction. It is the temple at which I serve. I’m interested in writing that is as obsessed with language and humanity as it is with anything else. I wanted a book that meaningfully engages with kink, and often, when I want something and I can’t quite think of an example of its existing, I feel tempted to do something about it.

CHEE: I suppose, for me it’s also, in terms of the story I contributed, about asking people to reconsider why they think something might be pornographic versus literary, and why they might condescend to porn. I think there’s something about those narratives where you connect to the somatic experience of the body really powerfully in a way that is threatening to some people. I recommend everyone read Angela Carter’s The Sadeian Woman. It’s a short book where she discusses the Marquis De Sade as the first moral pornographer, because he gave desire to women in his stories, which I think is such an interesting thesis to expand upon, especially from a writer like her.

KWON: Oh my god, I’m getting a copy today! It’s my next read. I will also add that I don’t quite understand why reasonable people believe sex should be in any way separated from other human experiences, in terms of its fitness for the page. Having sex with someone, even just wanting sex, that is a position of such vulnerability. And why, as fiction writers who spend as much of our time as we can thinking about people and how they are, why on earth would we cut ourselves off from this entire segment of human experience that means a great deal, in one way or another, to everybody.

LONDRES: R.O., in the intro to the anthology, you and Garth write that “Kink in these stories is a way of processing trauma, and also of processing joy, of expressing tenderness and cruelty and affection and play.” I would imagine that writing about kink is its own catharsis. How was it entering this territory in your writing for the first time?

KWON: Generally, when people publish short stories and they post a link online, most non-writer friends are not going to click on it. With this story I was like, I have a story in Playboy, it’s called “Safeword”. So many non-writer friends ended up reading that story. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll put it this way, I think part of what I love so much about fiction, and part of why I still really consider myself a novelist who sometimes writes non-fiction is because I love that sort of curtain of plausible deniability that fiction gives. It lets me be so much more honest. It lets me dig so much deeper.

CHEE: I was in an epistolary relationship when I was in my early 20s. I had moved to San Francisco, and I was working at a bookstore, and engaged in a lot of activism. I met someone at a meeting. We became pen pals and I wrote him absolutely filthy letters about what I would do to him if he was in San Francisco. I wrote my first poems as someone who was in love, and so I started out as a love poet. Then love, or at least desire, turned me into a sex writer. The letters worked. We ended up together in a relationship for three years.

LONDRES: That’s next level. Beats sexting.

KWON: Imagine… I wish you’d publish those letters, Alex. Damn.

CHEE: I think he has mine and I have his. It was really about creating an imaginary space where he and I could be together because he lived in New York and I lived in San Francisco. I learned a lot about sex writing in the process.

LONDRES: Let’s get into some of the stories in the anthology. In Larissa Pham’s “Trust,” Callum Angus’s “Canada,” and Roxane Gay’s “Reach,” it’s interesting that sex is the language that comes easiest to the couples in the story, and it ends up being the tool that allows them to communicate what can’t be put in words.

KWON: Well, when there is sex in a scene, that is often a time of maximum vulnerability. And times of maximum vulnerability are so central to what fiction is interested in, or at least the kind of fiction that I personally am excited about.

CHEE: That’s what’s so interesting and weird about it to me. In some ways it’s an introduction to all these categories of feelings that exist outside of those state recognized relationships and desires. The language around that as a result is difficult to find. It makes me think of a new writing exercise that I have for my students that came from a trip to a scent shop with Carmen Machado. There was a fragrance there called Violence, and we were like, “Oh my God. What does violence smell like?” That became the writing prompt.

LONDRES: Brandon Taylor’s “Oh, Youth” and Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror,” among others, demonstrate how traditional power structures are upended in the realm of kink. In these stories, youth, wisdom, economic privilege, even the very desire of your lover, are all leveraged as the characters see fit. What gives kink this power?

CHEE: I’ll approach it a slightly different way. Any time you don’t understand a relationship, or you’re like, “Why are they together?” Usually there’s that one thing that one of them likes that the other one knows how to do. That can keep you in a relationship for a very long time.

KWON: Wait, I fucking love that! Oh my gosh, like one hook.

CHEE: One hook. Even though that person may not seem very beautiful, or confident, or powerful, they will do that thing. Carmen’s story very much seems to me to fit that kind of a connection where the two lovers in that have this powerful attraction to each other. It seems like we know which one is the more powerful, and which one is the less, at the beginning. And then there’s a switch in the middle because the narrator, at some point, comes to understand what she possesses.

KWON: What can be marvelous about kink is the way it can transmute what could register as negative into joy, into pleasure, into connection. It can turn experiences of subjugation into a place where the power balance feels better. There are all these examples of people’s bodies eroticizing what we fear, and I just think it’s a miracle that we can do that. I was just looking this up yesterday. It doesn’t seem like any kind of a surprise that rape fantasies are some of the most prevalent fantasies among women. It’s something like, in the various studies, it averages to four in 10 women have occurring rape fantasies, and the assumption is that it is actually much higher because a lot of people don’t want to tune into it, and that’s, of course, rooted in all the ways in which it has been and is dangerous to be a woman in the world. And that’s terrible, but there’s something just also moving to me about that.

LONDRES: “Oh, Youth” and Vanessa Clark’s “Mirror, Mirror” blur the lines of transactional sex and genuine love and companionship. And R.O., your story “Safeword” complicates sex as both play and skilled labor. With the fall of porn Tumblr, gentrification of OnlyFans, deplatforming of sex workers on social media—not to mention the persistent narrative that conflates sex work with human trafficking—why is our culture still so antagonistic toward sex work?

CHEE: Obviously, the culture has a problem with sex work, but I think what we see here is a problem with sex that sex workers are made to pay a price for. This is something I wrote about in my second novel, The Queen of the Night. This way in which what was called the Demi Monde in Paris wielded this political power. These sex workers had the secrets of powerful people because they tended to the pleasures those men could barely admit to themselves, that they needed to live. That’s where the power comes from, and the trouble, also. It’s that slipperiness that Reese was talking about, where someone goes from being the powerful one to the helpless, and back again. This fluidity. That’s what they want, and it’s what they fear, and sex workers can offer that. They are both sought out for it and condemned for it.

KWON: I don’t quite understand why, as a country, as a society, as a world we don’t listen more to marginalized people about what they want for themselves. I feel as though all the sex workers I know and follow are so clear. Decriminalization, period. I can’t get my mind around why that argument is not compelling enough to people.

LONDRES: Congrats to you both on the anthology. I loved so many of the stories in it. What are you currently working on?

CHEE: I’m working on a new novel and another essay collection. The novel is something I’ve been working on for a very long time in a sort of background kind of way. And I’ve always told myself that I would get to it later, and so here we are. Now is later. That’s actually been kind of interesting and terrifying to address.

KWON: I’m working on my second novel. I’ve been working on it for five years. I was like, I really want this to be a six-year novel because my last one was a 10-year novel. It’s about two women. It’s about a photographer who becomes obsessed with a ballerina, first professionally, and then personally, romantically. With this book, I think the central question for me, or central fascination is, I feel, as a woman that there are things I am encouraged to want and there are things I am judged for wanting. Things I’m encouraged to want are having children, being a wife, being a daughter. What other people want from me is to take care of others. I’m interested in that because I feel I have to defend almost any other kind of desire, if it has to do with artistic ambition, if it has to do something with my body. Sex, food, any of it. The men I am close to do not seem to feel this pressure. I am fascinated by that, and also pissed off.