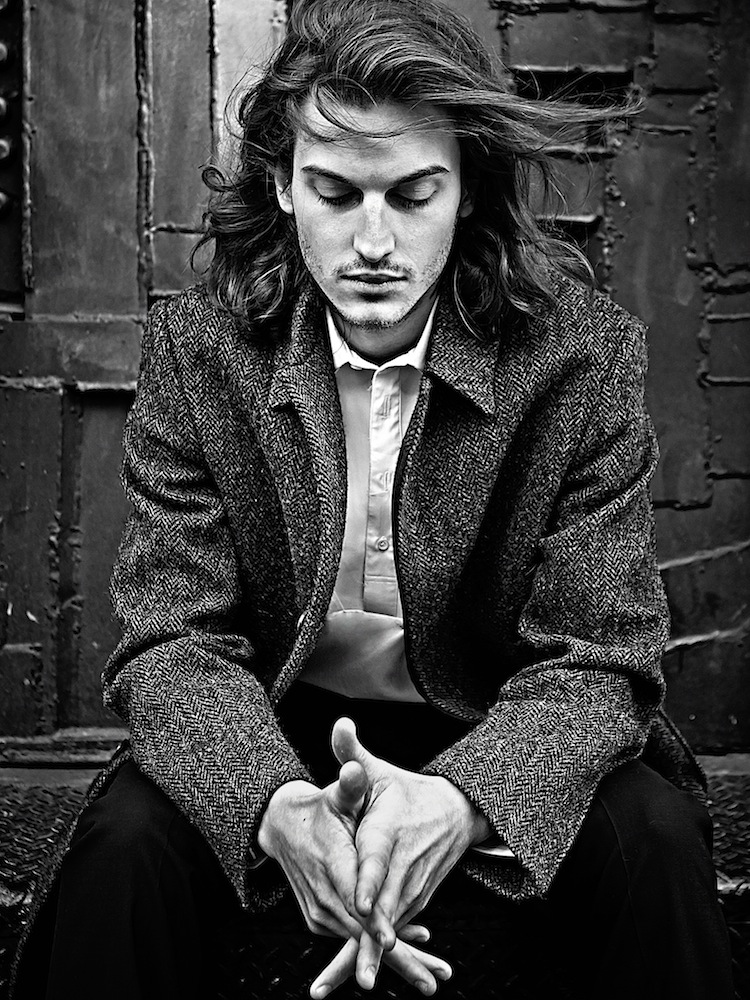

Peter Vack, in Focus

ABOVE: PETER VACK IN NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2014. PHOTOS: HAO ZENG. STYLING: JESSI JACQ. GROOMING: JENNIFER BRENT FOR EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS USING BUMBLE & BUMBLE AND HARRY JOSH PRO TOOLS. PHOTO ASSISTANT: BRIAN JONES. DIGITAL TECH: SIMON INGALL.

When it comes to 20somethings in New York, Amazon Prime’s new show Mozart in the Jungle is the antithesis of Girls. The protagonist Hailey, played by Lola Kirke (yes, sister of Jemima), knows exactly what she wants to do: play oboe with the New York Symphony, which recently replaced its longtime conductor (Malcolm McDowell), with an eccentric former child prodigy, played by Gael Garcia Bernal. Hailey’s a little less certain about how she will get there, or if she’s worthy, but her end goal is clear. The same goes for her love interest, Alex (Peter Vack), who is studying ballet at Julliard. “There are a lot of shows about young people that are interested in the question of ‘What am I going to do with my life?’ and ‘How do I fit into the world?'” explains Vack at a café in New York. “All of these characters are extraordinarily disciplined, passionate artisans. It’s cool to get to play a character who is young and living in the city and—although there are questions as the season goes on—knows what he’s going to do.”

Like his character, Vack always knew what he what he wanted to do. In his junior year of high school, the New York City-native transferred to the Professional Children’s School to have more time for acting. By the time he got to college—he studied theater at USC—he’d already been in a soap opera (As the World Turns), done several TV guest spots (including every actor’s rite of passage, Law & Order: SVU), and appeared in Richard III at the Public Theatre.

The full season of Mozart in the Jungle was released yesterday. Created by Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, and Alex Timbers, the show also stars Saffron Burrows as a cellist and mentor to Hailey, Debra Monk as an unimpressed senior oboist, and Bernadette Peters as the head of the Symphony. “It was a very good energy,” Vack says of the cast and crew.

EMMA BROWN You’re from New York originally, right?

PETER VACK: Yes. I was born in the West Village, and then when I was about four my family moved to what they joke is the suburbs, the Upper West Side. I lived there for most of my childhood. Then I went to school in L.A. and lived there for a bit. But now my whole family lives in Brooklyn. I live in Bushwick, my parents live in Williamsburg, and my sister lives in Crown Heights.

BROWN: Williamsburg seems very hip for parents.

VACK: My parents are actually very hip. They’re way hipper than me.

BROWN: Is your sister in the industry?

VACK: Yeah, she’s an actress as well. And a writer. She’s moving into making experimental videos. She just had the family act in one last night. She would give us random directions and film it on her cell phone. I don’t know how she’s going to use this footage, but we’ll see. It’ll be fun.

BROWN: Is she older or younger?

VACK: Younger, though now people are thinking we’re the same age, or that she’s older, which I don’t think she loves. I’m four and a half years older than her—it’s an interesting age difference. Growing up it feels like a big rift. Then you get older and you realize it’s not. But for a while there, we really didn’t have much to do with each other—mostly because I should have been a better older brother. I’m making up for lost time. I want that in print so she can read it.

BROWN: And your dad was an actor as well.

VACK: Yeah, when he was younger than me he came to New York to be in musicals and was in a number of them. He was in the chorus, but this was a time when he didn’t have an agent, he was just going to open calls, and he had and still has an incredible voice. I think he probably would’ve advanced in the world of acting, but he, at that time in his life, didn’t feel he could fully commit to a creative life—he had this voice in the back of his head that said, “I need to make money.” So that propelled him to open up an ice cream parlor, which then spawned into a number of different food businesses and took over his life for 20 years. He’s also gifted at business, which is a blessing and a curse, because if you have the kind of mind that he does where you can do anything very well, that in its own way is sort of limiting. Not limiting, but sometimes it’s nice to think, “Oh, I can only do this one thing.” Instead of feeling like, “I could theoretically, maybe, if I applied myself, could be successful in a number of different fields.” That can be overwhelming. Sometimes it’s nice to have this myopic vision for your life and that’s the only thing you can imagine yourself doing.

BROWN: Lola Kirke is also from New York. You must have had a lot in common when you were working on Mozart.

VACK: We did. My character is actually from Nashville and I remember when we auditioned, one of the notes was it seemed that we were too much New Yorkers—something about our energy seemed very New York. I had to dial down my New York energy in order to get the part.

BROWN: How do you do that? I wouldn’t even know where to start.

VACK: I have a subtle accent. Turning off some of the neuroses. [laughs] As hard as that is for me, it’s possible, but for very brief moments. For the length of time it takes to shoot a scene.

BROWN: Did you consult any of your ballerina friends from the Professional Children’s School when you were preparing to play Alex?

VACK: I took ballet for two years in high school and then in college on and off, and I went back into class. I’m nowhere near good enough to be a professional, but it’s great to be in that environment. The discipline is so impressive. And just being in class and forcing your body into those positions, that’s enough.

BROWN: Are you the one doing all of the flips in Washington Square Park then?

VACK: Yeah. That is mostly me; I worked a lot with Kelly Devine, who is the choreographer. We had a lot of fun and worked very hard on those dances.

BROWN: Since the full season of Transparent came out, Amazon seems like a much more legitimate source of original content. When you signed on to be in Mozart, were you at all apprehensive?

VACK: My feeling was, “This is the future.” And what’s great about a place like Amazon is they really give the creators of their shows freedom, and there is less limitations imposed on them creatively than when you’re making a conventional network show. I was actually very optimistic about and excited by the fact that it was going to be on Amazon. That never really worried me.

BROWN: You’re sort of removed from a lot of the other, older characters on the show. Did you get to interact with Malcolm McDowell or Gael Garcia Bernal?

VACK: No, at least not in this season. But Malcolm is so cool. I’ve met him. Jason Schwartzman and Gael Garcia Bernal are so nice. They’re, like, faultless individuals.

BROWN: You mentioned you’re a filmmaker, what kind of films do you make?

VACK: I made a short last year called Send that played at South by Southwest and AFI fest and about a dozen other festivals. Then I’m developing a feature that’s sort of a conceptual continuation of that film that I hope to go into production with soon.

BROWN: You were also in a movie at South by Southwest this year.

VACK: Yeah, I was in two films there: I Believe in Unicorns and Fort Tilden, both of which should, hopefully, have some life in the world. They’re great films.

BROWN: I saw I Believe in Unicorns. It was intense. Your character…

VACK: Is not so nice.

BROWN: One actor recently told me that you need to like the character you play, even if they are a horrible person. Do you feel that way?

VACK: Yeah, I actually agree. I think you should identify with your character, but plenty of people like themselves and hate themselves. You just have to find out what’s truthful for the person you’re playing. When people talk about that, I think what they’re saying is that as an actor, as Peter, you don’t want to make a judgment that comes from your worldview about the character. Your judgments should be coming from the place of the character, and within that space, yeah, sure, you could love or hate yourself or whatever you think is most appropriate. But when you see a movie, and you are removed, then I feel like it’s totally fine to have judgments about the person you played. Then you’re seeing it as an objective audience member. Like, when I was in I Believe in Unicorns, I didn’t really think about how I was coming off, because I didn’t think that character would. But then as Peter watching, I was like, “Oh yeah. That guy’s not so nice. At times he’s really kind of a schmuck.”

BROWN: Can you remove yourself from your character when you’re watching your own work?

VACK: It really depends. Because when you’re watching yourself work, you’re not really an audience member for yourself. Even being confronted by your own image can be jarring sometimes. The experience of making a movie or a television show is this really full one, and sometimes you see it and even if it’s a great piece of work, it’s not the experience—it’s almost sad because it reminds you of something that isn’t anymore. Seeing a movie you’re in is nothing like seeing a movie you’re not in.

BROWN: You have a few films coming up as well. You’re in The Road, a short directed by Hannah Fidell, who did A Teacher.

VACK: Yeah, she’s a good friend of mine and someone I admire a lot. I guess it was last year, she called me and said, “I want to make this short film because I’m about to direct a feature.” It was her and her friend Carson Mell, who’s a fantastic writer, and then her friend Andrew [Droz], who’s a great DP. We got together and made this improv road trip movie and had a blast. Then she had a small role for me in her feature [6 Years], that obviously I said yes to. We shot that in Austin. I’m excited to see it. It’s going to be good. I play an unsavory character in that one too though.

BROWN: Thanks. I’m warned. How did you meet Hannah to begin with?

VACK: I feel like we’ve been friends for so long, but we actually just have the same agent and we got put together for a general meeting and then hit it off. [Those meetings] usually feel much more like business, and that one felt like hanging out. That’s what you want it to be. I just did my friend’s film—this guy Harrison Atkins who’s a great filmmaker. He just makes movies with all his friends, and I think that’s all what we’re striving for—to feel like we’re among friends and people who care about each other. I’d like to think that good work comes from that—from a sort of loving and friendly environment.

BROWN: What about Nancy Meyers’ new movie, The Intern?

VACK: I have a couple of lines in that movie. Just a couple, but it was very fun. A couple of lines with Anne Hathaway.

BROWN: Are you her random boy toy?

VACK: Not exactly. [laughs] In that film Anne Hathaway runs a fashion blog and I play a tech advisor. I hope I make it into the film. I say something about the interface of what we’re working on and then I get sent out of the room and I never come back. But it was fun. Nancy Meyers makes great films.

BROWN: With something like that, because you have had quite a few significant roles, is there any part that would be too small? Or is it more, “if the project is good I’ll do it”?

VACK: It’s usually if the project’s good, I’ll do it. It’s always nice to have a large role, but if it’s a great small part, those can be so much fun. Size is less important than quality, always.

BROWN: In terms of your long-term ambitions, do you want to do acting as well as filmmaking?

VACK: Yeah, in a way I see them as almost the same thing. One informs the other. What’s nice about writing and making films is that being able to see a film from the outside—from the inception through production and then completion—just informs what you’re doing when you’re an actor. And when you’re an actor, it informs the decisions you make when you’re making a film. It’s using two different sides of your personality.

BROWN: What’s something that you learned as a filmmaker and then applied to acting?

VACK: I was really able to confirm something that I knew on some level before I’d made a film. The best actors know how to really relax. Because in film, a lot of the decisions are made in the editing room, so when you’re trying to guide your performance too much—always it’s a push and pull because you can’t be too relaxed. Too relaxed and it’s like, “What are you doing?” Too tense and it’s not good either. [You need to] know that you are just one piece in this puzzle and let that be freeing and liberating instead of making you feel lost. If you feel like you’re working with good people, you give them your humanity and just let it happen. You would almost think it would be the opposite, but making a film sort of made me freer in my acting.

BROWN: Have you ever been in a situation where you don’t entirely trust the people you’re working with and you want to protect your performance?

VACK: Yeah, and we just hope we’re not in those situations so often. But there’s nothing you can do. If you’re in something and you feel like it’s not going well, what can you do about that? It’s out of your hands. No matter what you do, you’re not going to fix that as an actor.

THE FIRST SEASON OF MOZART IN THE JUNGLE IS NOW AVAILABLE TO STREAM VIA AMAZON PRIME INSTANT VIDEO.