AFTER HOURS

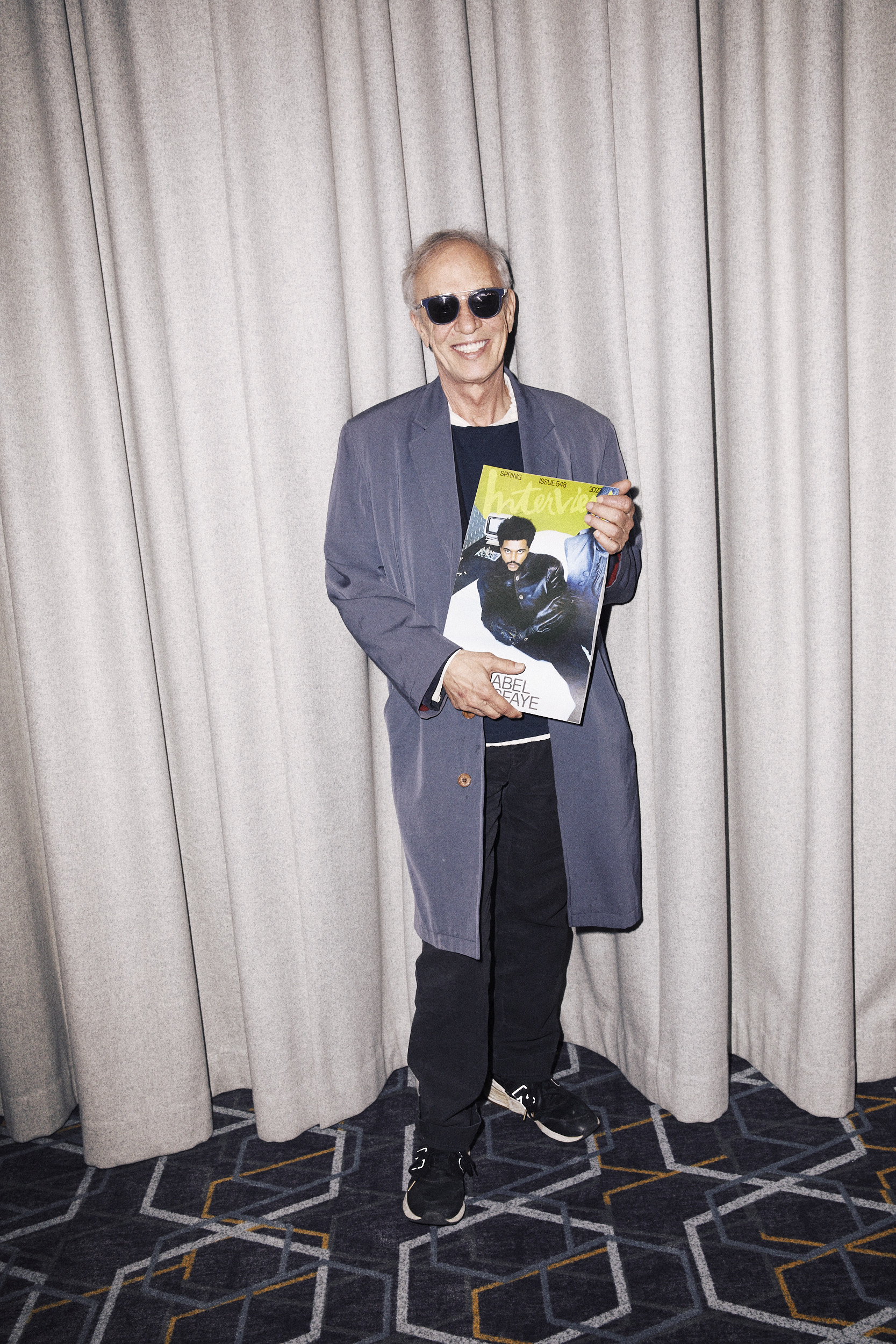

Peter Gatien Is the King of Clubs Forever

Last week, New York legend Peter Gatien, often referred to as the “king of clubs,” appeared on a panel hosted by the NYC Office of Nightlife at the Responsible Hospitality Institute’s 2023 Sociable City Summit with our editor-in-chief Mel Ottenberg. Gatien, who in the 80s and 90s owned and operated a cluster of the city’s hottest destinations, including Limelight and The Tunnel, got candid with Mel about the glory days of clubbing, the importance of catering to a gay crowd, and the scourge of the Giuliani administration. Their talk, edited lightly for clarity, appears below.

———

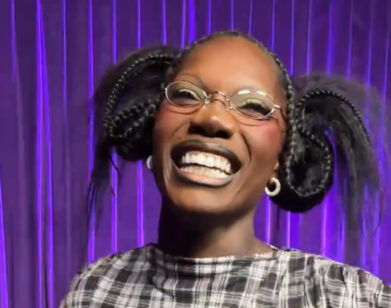

MEL OTTENBERG: Thank you so much for asking me to interview Peter Gatien, legend, icon, true king of clubs for New York and beyond. It’s a pleasure to have you here, Peter.

PETER GATIEN: It’s so much fun being in New York. It’s a great city. I miss it.

OTTENBERG: We miss you. How was the trip here?

GATIEN: I never jet through customs, but this time it went really smoothly. And it’s gotten better over the years. I got a waiver probably eight, nine years ago that allowed me to come back. In the beginning, it was always in secondary, and now it’s smoother than it used to be.

OTTENBERG: Before I get into what I wanted to ask you, I’m curious. When you come and you have this rush of emotion and memory about New York, what are the things club-wise that you’re thinking of?

GATIEN: I gotta get my licks in when I can. I’m reading The Washington Post this morning and they’re talking about Dominion Voting Systems and their next target is Rudy Giuliani. I break out into like, “Oh my god!” It reinforces karma. And he deserves worse.

OTTENBERG: Big round of applause for that.

GATIEN: I come in the city, it’s just the energy in New York, everything from the retail, the clothing, everything is around here, the energy and the creativity. And it’s well beyond Manhattan. Now, I think, 20 years ago, you never even thought of going to Brooklyn.Three, four years ago, before COVID, I got a fair amount of calls wanting to see what I thought of a different space or whatever and I explored the Brooklyn scene and I gotta tell you, I was really impressed. Especially places like House of Yes. There’s some places that are really getting it. One thing I loved about what we did in the 90s, especially in the ’80s also, is we really put a lot of energy into getting a diverse crowd. And I think a lot of it has evolved now where everybody looks the same in a lot of clubs. That whole bottle service, whatever, probably makes a lot of money for clubs. But I think we were much more egalitarian in our day than you are now. You you didn’t have to pop $250 or $500 for a bottle or a table or whatever. In fact, you had a better chance of getting into the clubs if you were creative with your clothes. You had a much better chance of getting in than somebody who’s pulling up in a limousine. Just the way it was.

OTTENBERG: Let’s go back to the beginning of you in New York, which is 40 years ago exactly, right?

GATIEN: Yeah, I moved here in ’83.

OTTENGERG: And opening Limelight was easy or hard?

GATIEN: Well, navigating anything in New York City is really difficult from the billing department, to complying with CFOs and whatever. This is probably hard to believe for most of you because you’re younger, when we opened Limelight, literally, big box stores like Bed Bath and Beyond, those were abandoned buildings. There was nothing there. The whole of 20th Street was all light manufacturing. There were no restaurants, so it was really an oasis. I mean, there was Sixth Avenue. But New York was…

OTTENBERG: Desolate at night.

GATIEN: Yeah, it was more raw. It just was. 16 years old, I remember reading about Times Square dying. First time going to New York, visiting Times Square. Yeah, there was a rawness to it, but there was certainly a lot of charm to it back then, too. Back then, a lot of staff was just on Avenue A, B, and C. It was affordable.

OTTENBERG: Did it hit right away?

GATIEN: In my experience anyway, they hit right away, or you’re in deep shit. I guess a lot of people are in the business who certainly understand, but a lot of people think you open your doors, you have a terrific sound system, and doors are smoking, people get in. It doesn’t work that way, man. You have to work it. You have to go to events. So we put a lot of energy in a real diverse crowd, which meant different interests, different invites, even for the same night, targeting different crowds, whether it’s a literature crowd or art crowd or whatever, and then you do special parties. You want to get a Mick Jagger or somebody’s birthday party, this or that, getting Page Six. And that was your marketing, [because] we didn’t advertise, there was no radio or anything like that. We never did that mass media stuff.

OTTENBERG: So one of the big parts of your jobs was knowing who the coolest people were. Hiring them from other places and getting them to do their thing, right?

GATIEN: Not necessarily. When I got here, the benchmark was Studio 54. But Studio 54, at that point, had their troubles in about 1980, ‘81. What I called it was the era of miles of neon chrome spinning wheels had been done to death, and there’s no way I thought, “Okay, I’m gonna come to New York, I’m going to have more spinning wheels than Studio 54 did,” or “I’m gonna have more chrome or neon.” That’s not going to work.

OTTENGERG: It wasn’t cool anymore.

GATIEN: It wasn’t going to be cool in three years. If one club has 10 spinning wheels, you have 20, big deal. So I just thought art and architecture were the way to go. And my instructions to the real estate person had been, “Please find me a church,” something architecturally interesting. High ceilings, obviously. And lo and behold, the church was a drug rehab center and a woman had gotten in trouble. And she had paid $600,000. She’s asking $1,600,000. I looked at the building, didn’t negotiate. I didn’t say like, “Take 1.595.” It was like, “Where do I sign?” You know, churches are perfect in that they have high ceilings, architecture is incredible, and a lot of doors. So to comply with CFOs and that kind of stuff, it helps.

OTTENBERG: You talk in your book about the real sad mid-80s when AIDS was really at its peak, when you really didn’t know how you were getting it. What kept it alive at that point? Because you really explode around ‘88 and then into the 90s. What kept it going?

GATIEN: Basically, I always felt that the gay crowd continued with so much energy on any given night that we always tried to have an event. There would always be at least 20% gay crowd. And they created Interview. They came with the costumes, they were on the dance floor. Not that the streets were boring, but the gays were much more inspiring. There’s no other way of putting it. So by ‘85, I remember having the staff, healthy, good-looking guys, and then three weeks later, they looked like Tom Hanks from Philadelphia. I mean, it hit that quickly. We got to know those people. It really hurt. It really hurt. So anyway, at that point, we went after, quite frankly, the bridge and tunnel crowd. There was just no gay activity. New York and San Francisco got hit the hardest by far. Chicago hadn’t, and London hadn’t. And that’s when I decided to take the show on the road, so to speak. So we did London and Chicago back in 85, ‘86, give or take. But we had to develop a base of tourists. We were always good for 400 people, 400 Monday, 400 Tuesday. Maybe 600 on Wednesday, 5-600 on Thursday, and more on tourists. We had everybody from Jack Nicholson to Tina Turner. Pearl Jam. I mean, we had a lot of stuff going on back then, so we developed a reputation that allowed us to survive.

OTTENBERG: And then Warhol died, and everyone said downtown was dead, downtown was over. That’s when everything really started pumping for you.

GATIEN: When ‘85, ‘86 hit, that’s when there was a real cold reality that people were scared. It looks like nobody knew how they got it back then, whether it was dirty glass or a kiss or whatever. So no, I did my stuff in London and in Chicago. And then in the early 90s, Palladium was, I don’t want to say really hurting, but the owners didn’t really want it anymore. And they basically gave me the place for free. And Tunnel was shut down at that point and we tripled the size of it. And then in ‘93, ‘94 you had Clubs USA. [In the] 90s, there was a revival and then people figured, “Okay, you don’t get AIDS from a dirty glass.” And I think the gay community probably curved its promiscuous [activity] a little bit also.

OTTENGERG: When you had four hot clubs running at the same time, and you’re working 16 hour days, were you loving it?

GATIEN: You love it because you hate it so much. Compared to the kids watching Ed Sullivan, you see the guy with the plates, spinning them, and you’d have to run from one pole to the other. Well, that was me on steroids. And you’ve gotta understand the diversity. We were doing, give or take, 28 parties a week, which meant printing invitations, designing invitations, distributing invitations. I didn’t have outside promoters, but for the majority of my staff I was their only employer. I remember going to Sunday Night at Tunnel one night and there’s Jay-Z and then going to Limelight and and having Pearl Jam and going to club USA where we used to have a night, I think it was “Bump,” where there’s 3,500 sweaty, pumping, muscle guys in there. It was hotter than hell. And then going to Palladium, we remember doing Broadway Bears where Nathan Lane is hosting. So yeah, it was exciting as hell. Everything from the security to ticket takers to cashiers to bartenders, you gotta keep an eye on all those people. You had systems developed for that kind of stuff. And then cops, especially after Giuliani got in, were a real nuisance. I remember nights where they’d come at 11 o’clock they’d say, “Okay, nobody can come in until we do our inspection.” Hold the door up for an hour-and-a-half, literally 2,000 people. They come out and then give you a ticket for disorderly premises, too many people on the sidewalk. It was that kind of insanity. I don’t want to brag or anything but I was sort of the face of nightlife. But Giuliani was brutal on all of us. I think me, especially. He’s a mean son of a bitch.

OTTENBERG: Well, it must be good coming back to New York, knowing that New York really, really, really hates Rudy Giuliani. We fucking hate Giuliani. Maybe we hate Rudy Giuliani more than Donald Trump because I mean, Donald Trump you can laugh at, but with Giuliani, there’s no fun to it. It’s just horrible.

GATIEN: They’re both megalomaniacs, and that’s the problem. I remember doing an interview with the Daily News. If Giuliani had the resources of the President of the United States, with the CIA and the FBI and every other alphabet agency, could you imagine? Just with the New York Police Department, he was beyond Nazi brutal. But anyway, let’s stop talking about that.

OTTENBERG: Okay. So you’ve got four clubs. Let’s say none of this shit happened, did you have plans for New York that didn’t happen?

GATIEN: To be honest with you, I was 43 or 44 when the shit hit the fan. My plans was whether to get into the hotel business, or get into the movie business. I had executive produced A Bronx Tale, executive produced a movie called Faithful. And I met a lot of the big studio guys and said, “These guys aren’t that much smarter than I am.” Not that I thought I was gonna become a studio head, but I knew I could go there. And then I was 44 just like, “Do I want to be up at six o’clock in the morning all the time?” The answer is no. So I had a loose plan of selling. I think I had an offer back then, like $50 million for two of them. But anyway, it didn’t happen.

OTTENBERG: I used to go to Tunnel a lot. I’m trying to remember what Tunnel was like in ’94? Because I was definitely going in ‘94, Friday night.

GATIEN: It was sort of a fashion-oriented night. You remember, we had the library downstairs. So there’s probably about four dance floors in the place. And then obviously, the rooms on the side, you could jump into all the balls. It was a hip night. Your numbers are 3,500 people. It’s hard to get 3,500 reasonably hip people. [Audience laughs]. Those are big numbers.

OTTENBERG: No, I remember. I must have been 19 or 20. It was the summer and we’d go to Tunnel at like 1am, and I’d be like “These people are not right.” And then 6am hits and suddenly out of the blue, everyone started to look great. And I’m like, “Wait a second.” I didn’t know about after hours and shit. So all my friends would leave and I’d be so tired just watching it slowly transform into something else. It was incredible.

GATIEN: Listen, somebody has to pay the freight in the nightclub business. Back then I think we were charging $15 to $20. So it’s mostly tourists and people who want to be part of the Manhattan scene or see it. The way that was orchestrated, in the early part of the night, two or two-thirty was probably 80% straight, 20% gay. And then by three o’clock, four o’clock, all the numbers are inverted. And I have a feeling that’s what you’re talking about now. And I think the more seasoned Manhattanites know the real action starts after one or one-thirty.

OTTENBERG: Yeah. By six, it’s a whole other crowd. But when I was in college, I did not know any better. Alright, we’re almost running out of time. I can talk to you forever because I have many questions for you. But what sage advice can you give this crowd of nightlife people, Peter Gatien, as the king of clubs forever?

GATIEN: Like any organization, your support staff is what will make or break it. It’s just that simple. And if you can try and inspire a loyalty, not that you’re doing God’s work by any means. But especially in New York, you’re doing something that’s gonna become institutionalized in years to come, and you’re part of a culture to make the city so special, and you can have a lot of fun. Everything from management, security, tickets, whatever, [it’s important] that everybody’s pleasant, everybody’s happy. You can’t be rude to people. It is not that world out there. But it’s a complicated business, not to discourage anybody. It’s a complicated business.

OTTENGERG: I was watching your daughter Jen Gatien’s doc last night, Limelight, which I highly recommend to people. It really made me want more from that time, you know what I mean? When you Google Club USA, you don’t see that much. Is there anything coming up in the future where we will get to see more of your legacy?

GATIEN: Nick Pileggi, the guy that wrote Goodfellas, wrote a screenplay and we are developing it and came to the decision that the story was too long to tell in two hours. So we’re in development with the people from Euphoria. And when I say development, I mean development. I don’t mean we’re starting to shoot next week or next month. But we got a few very serious writers [attached] to it. I’m hopeful. It’s a story about New York also, it’s not just about me. Transformation in New York. And I hope that we get it done.

OTTENBERG: To be continued. Peter, thank you for being here.

GATIEN: It was a real pleasure, everybody. Thank you.