Paul Lisicky’s Memoir “Later” is a Love Letter to Provincetown

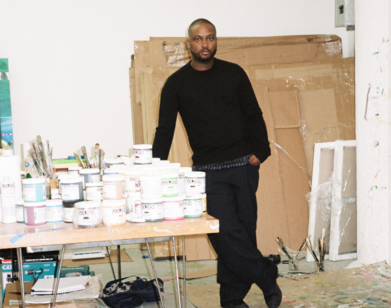

Paul photographed in Provincetown in 1992 by CA Robinson.

The subtitle of Paul Lisicky’s new—and electrifyingly visceral—memoir Later is “My Life at the Edge of the World.” In the 21st Century, there are a lot fewer edges of the world for queer life than there used to be. The edge is the margin, the sideline, the area just beyond the camera’s central focus, where the exciting magic, experimentation, art, and alternative thinking takes place. For Lisicky, the edge of the world is Provincetown (or “Town,” as the author calls it), the seaside hamlet on the northern tip of Cape Cod that has long been a haven for both artists and gay men. The author arrived in the early ’90s, a man in the prime of his early thirties awarded a writing fellowship, curious as much about the larger world as the various uses of his sexuality, physicality, and creative impulses. Of course, alongside all of the energy and excitement of youth, is the dark reality of AIDS, and even at the edge of world—especially here—those deep, long shadows threaten to overtake the sun. Lisicky’s memoir is less a coming-of-age than a coming-to-terms, and he cleverly divides up the text into short meditations on sex, loneliness, ambition, heartbreak, and hope. Unblinkered honesty is part of the book’s appeal (“Hurt is my biggest drug,” the author writes, “even though I don’t often say that to myself. It’s always so tempting to go there, to get that surge, that fix. What else out there, aside from sex, makes me feel more alive from the inside out?”). But the book’s biggest achievement is Lisicky’s rare talent for soaring high with his prose without ever feeling he’s lost touch with the ground. There’s a lot of poetry going on in these Provincetown musings, and a lot of love and pain. I spoke with the beloved 60-year-old New York writer about the importance of finding the world’s edge.

———

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Most of us have a city or town that we found when were young that developed into a love affair and that even after we move away. Later seems like a book devoted to your love affair with Provincetown.

PAUL LISICKY: I loved Provincetown. And when I was a younger person, I longed for Provincetown on so many different levels. It wasn’t just because it was a queer community; it was also because it’s a place where you could be an artist. Most of the places I lived in always had something lacking. So it was the right place for me to be, especially at that point in my life.

BOLLEN: So often when you think of queer communities, it tends to be in an urban metropolis. What’s special about Provincetown is that it’s so remote and fused with raw nature.

LISICKY: The fact that it was hard to reach intensified its aura. And even though it wasn’t an urban place, it was urban enough. There were plenty of people who’d migrated there from the East Village or Boston and brought a sense of urbanity to small-town culture. So Provincetown was fed from multiple sources. And it wasn’t snapped off and precious. It felt alive and active.

BOLLEN: When did you start working on this book?

LISICKY: I had started a version in 2015 that was in past tense. It was linear, chronological, and after about 100 pages, it started to feel too resolved and distant, and had a little bit of that manufactured wisdom that I’m really wary of. So I put it aside. Then I came back to it later and tried to mess it up a little bit. I switched it into the present to create some sense of immediacy. And I started introducing some shorter sections that weren’t so much narrative time as poetic time. I feel like in each of these short sections, the stakes are high. They’re moments of transformation. But really as soon as I sat down and wrote one memory, I was surprised by how many I could conjure up. I think that’s because I remember that segment of my life with more clarity than any other passage since. And I think that has a lot to do with living so close to death and illness. It wasn’t an abstraction. It was present in the community.

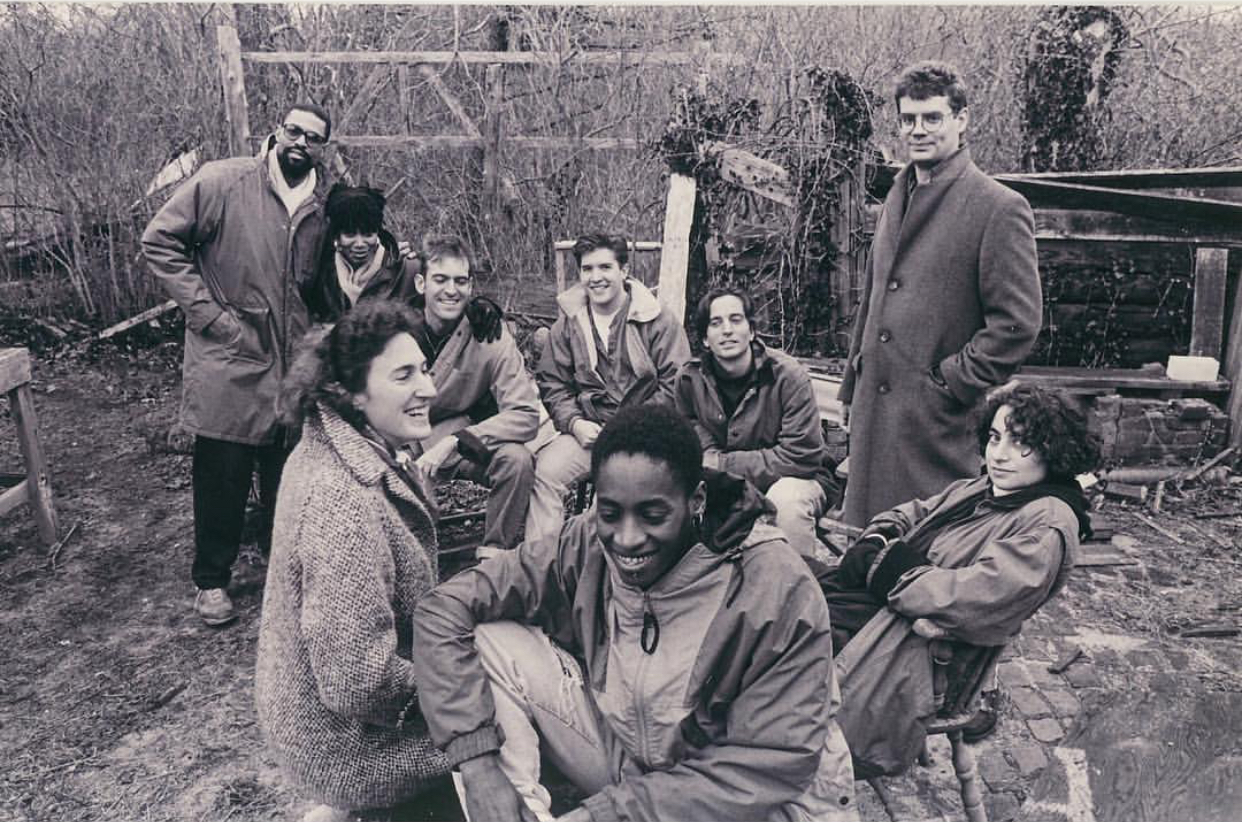

Paul Lisicky (back row, third from left) with the Fine Arts Work Center Writing Fellows in 1991. Photo by CA Robinson.

BOLLEN: I’m interested in that idea of “manufactured wisdom.” What kind of wisdom were you throwing on this narrative that didn’t seem to fit right?

LISICKY: I think there was a tendency towards something that felt—this sounds like a pretentious word to use—aphoristic, by which I mean I was universalizing about certain experiences and making statements that were totalizing. And I really didn’t want to write the official book of queer life in Provincetown in the early 1990s. I wanted to give some room for the possibility of other stories. I didn’t want to own it. And it took me a long time to arrive at that, because everyone has their own Provincetown. And everyone speaks about it in a very personal, mythic fashion. Mine is just one particular account.

BOLLEN: That’s very generous of you as a writer. I think most writers, when picking a place, want to own it. They want to write the definitive work set there. There’s a horrible colonist in writers to own the locale. I’m impressed that you were willing to check that impulse.

LISICKY: I’ve been on the ferry or walked down the street enough times to hear someone explaining his Provincetown to a new arrival, and they’re totally getting it wrong, and being annoyed with that person. And yet I keep my mouth shut and respect that person’s attachment [Laughs].

BOLLEN: There are some potent forces doing battle in this book—and sometimes within the same sentence. On one hand, there’s a great sense of life and youth and freedom and desire. And right at the same time, there’s death and finitude and suffering and fear of catching a disease.

LISICKY: Those contradictory forces felt like a life machine, for lack of a better metaphor. I mean, I never felt more awake and present. And I don’t mean to idealize it because a horrible illness was happening in the midst of that experience. I did feel like every day I was up against the possibility of an ending, up against the possibility of not seeing that checker in the grocery store on Thursday. Or someone who’d been in good health suddenly coming down with pneumonia. There was a tremendous sense of on-the-spot-ness about those days.

BOLLEN: At one point in the book, you talk about how today there’s something of a morbid nostalgia for the 1980s and early ’90s, romanticizing or fetishizing that era of AIDS in a way that really negates the utter of horror of it.

LISICKY: Yeah. You see it in fashion everywhere. But all of those voluminous clothes and bright colors, that was all in resistance to wasting and illness and despair. And maybe, for example, Billie Eilish‘s clothes make a lot of sense for these times. For us it was a lot of big clothing, like armor covering the body.

BOLLEN: You do manage to get some of the eccentric, idiosyncratic characters of Provincetown onto the page.

LISICKY: The community there really drew me to that place. I’d always thought of myself as a loner, the kind of person who had a few really close friends but was tremendously uncomfortable and incapacitated in groups. But when I got to Provincetown, I felt relaxed and welcomed and eager to be with people. I still remember those early walks in town, down the street, and how my stance was different. And I wanted to get some of those major figures of that time down.

BOLLEN: In this memoir and in your last one [The Narrow Door], you write about your most intimate relationships, often at their most intimate moments. I’m curious, when you write about someone, whether they are living or dead, does it change your relationship to them?

LISICKY: I’m sure it does. Because it’s usually the case when I start to examine someone, I start to see why I was drawn to them. In the case of my ex, whose name is Noah in the book, I didn’t realize how important it was for me to hold his hand in public. And to summon that up taught me something about our time together.

FAWC Fellows 92-93 (Paul Lisicky is fifth from the left.) Photo by Joel Meyerowitz.

BOLLEN: You started Later on a scene with your mother. And you end it with the passing of your father. I was struck that you bookended this moment of freedom with reflections on your parents.

LISICKY: They felt really present to me during those years. And to them, I’d done something rebellious by leaving the community of my family behind. I think on a certain level it was experienced by them as a betrayal. And even though they loved me, it was an ongoing negotiation, often on a daily basis. Mom was scared that I was going to get HIV and that she’d lose me. And I thought it would be a mistake to undervalue or disrespect that worry on her part. She was someone who’d lost so many people in her life that it was in her DNA to worry. My parents chilled out a lot after those years, and by the time I was with my ex, Mark, we would socialize together and visit them in Florida and it was like something huge had shifted. But those Provincetown years were a transitional point in our relationship. My freedom scared them because it must have summoned up their own problems, their own particular situations about attachment and loyalty.

BOLLEN: Tell me about the title. Why did you name it Later?

LISICKY: The temptation was to pick something super-poetic, and I thought no. I wanted it to seem offhand and not laborious. In retrospect, I think it refers to the last years of bohemia. It was the last years before protease inhibitors became available and accessible. And it was the last years before the internet where people had only each other to make up a community. Right after this period, the global LGBTQ culture arose, and it was branded and commercialized and it became a different thing. It was really the last days of an era.