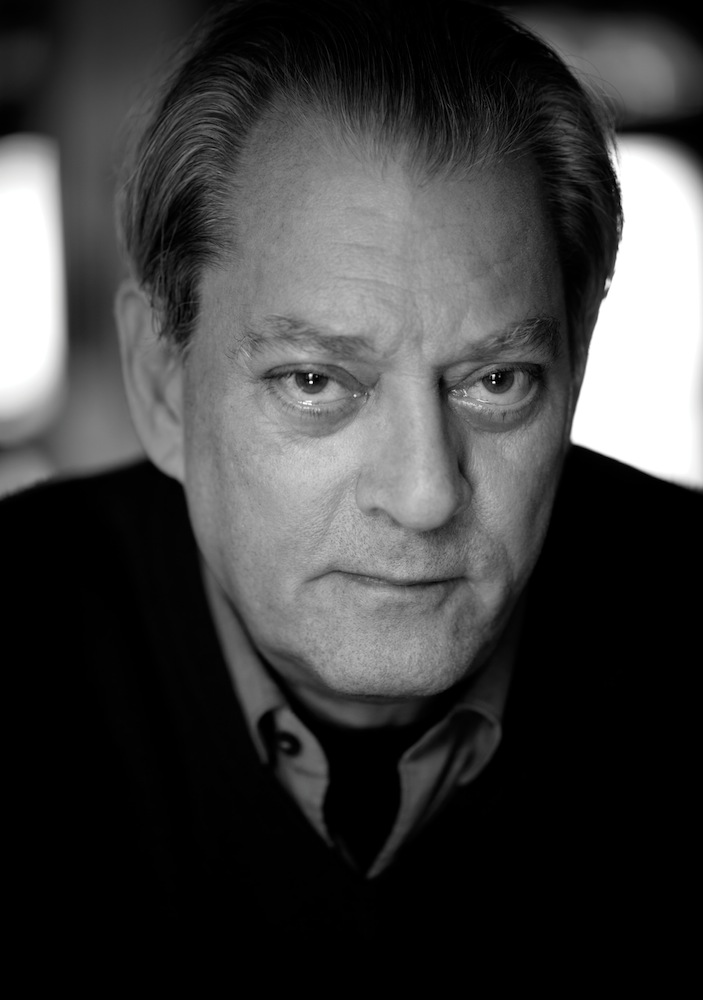

Paul Auster

“Is this Paul Auster?” asked the voice. “I would like to speak to Mr. Paul Auster.”

When I called Paul Auster up at his house to ask if he’d be willing to be featured in Interview, I was tempted to open with this dialogue. For the uninitiated, it comes from the first pages of Auster’s 1985 meta-masterpiece City of Glass in his New York Trilogy, where a mistaken late-night phone call asking for the author/detective leads the protagonist into a maze of shifting identities and herrings that are all the same shade of red. In the course of a literary career spanning more than 30 books, the 70-year-old novelist has become America’s foremost experimenter in the boundaries and limits of fiction, authorship, form, and the very notion that the traditional narrative arcs are sound bridges to transcendence. Or to recast that last sentence as a positive, Auster offers an entirely new direction on what fiction and writing can do, new possibilities (often, a mise en abyme of fictions inside fictions inside fictions or terrific Geryon-like creations fused from fiction, autobiography, and historical record). Auster’s books seem to contain detectives without a crime, or crimes with detectives, missing persons who are right in front of you, or characters that—to steal a line from his ingenious 1992 novel Leviathan—are as mysterious, seductive, and unknowable as “a hole in the universe.” Auster is often described as a master gamesman, a sort of literary chess wizard, but make no mistake, his cleverness does not stick a foot in front of the beauty and momentum of his prose. Over the years, Auster’s vast inventiveness has also led to a number of fascinating collaborations—from author J.M. Coetzee to artist Sophie Calle—and even a second career as a four-time feature filmmaker.

Another pervasive notion is that Paul Auster is more celebrated in Europe—particularly France, where he spent a few years after college—than the United States. No question, he’s immensely influential in Paris, which has always championed our more transgressive writers. America may be less vocal in its reverence, but Auster is nevertheless considered one the most hallowed living writers, perhaps only less glorified because he still seems to be at the top of his game. His latest novel, 4 3 2 1 (Henry Holt), might well be his sprawling American opus. Here, Auster again disrupts conventional structures to deliver the four simultaneous lives of one Archie Ferguson, the New Jersey-born, white, Jewish male protagonist who enters Earth in 1947 as the son of a large-appliance salesman and an erstwhile photographer’s assistant (not bad odds, all things considered). From there, the trajectories of the four different Fergusons shoot out (and occasionally knock together) like billiard balls on a table with only one pocket (death). Harnessing the history of mid-20th-century America (from the Kennedy assassination to the protests at Columbia University and beyond), 4 3 2 1 is an investigation of the manifold influences that shape and determine an individual life: those coming-of-age forces like financial, social, and familial atmospherics along with their invisible, apolitical colleagues like coincidence, chance, and luck. Over the duration of this astonishing novel, some Fergusons fare better than others, some get their heart broken, some win, some fall. Or as Ferguson-4 realizes early on, “Everything solid for a time, and then the sun comes up one morning and the world begins to melt.”

Auster continues to write gorgeously about the city he calls home (“dear, dirty, devouring New York,” he writes in 4 3 2 1, “the capital of human faces, the horizontal Babel of human tongues”). He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, the equally brilliant writer Siri Hustvedt. He does not use a computer, a cellphone, or e-mail. And for a novelist who has blurred and complicated identity arguably more than any other in the past 50 years, he is incredibly warm and magnetic to speak with—even to a relative stranger like myself on the other end of the phone. Needless to say, I did not try the City of Glass quote on him and he agreed to the Interview piece. To find out more about the nonfictional Paul Auster, we asked his longtime friend, filmmaker Wim Wenders to give him a call from Berlin. Wenders was just getting over a cold. —Christopher Bollen

PAUL AUSTER: How are you feeling? Are you any better?

WIM WENDERS: I am a little better, yes. I was under the weather, but I’m slowly coming out of it. It’s a pleasure talking to you, so I consider that a part of the healing process. Are you home?

AUSTER: I’m home. I’m sitting in the living room in a big, cozy green chair. I’m trying to be as comfortable as possible. Where are you?

WENDERS: I’m in my editing room. It’s relatively comfortable. I have a chaise lounge in front of me. I can always go over there and lie on it. Now, when 4 3 2 1 comes out in Germany, how is the poor German translator going to cope with it?

AUSTER: Well, they told me, and I’m amazed, that they hired a team of four translators to work on it.

WENDERS: Like the Bible, it’s also a team.

AUSTER: Exactly. [both laugh]

WENDERS: Donata [Wenders’s wife] and I have a big bookshelf, which we call the fence. Last night I went over to it and realized you fill three bookshelves in that thing! Three entire shelves are only you! Your novels, essay books, memoirs, translations. It dawned on me: you must be one of the most prolific writers on the planet.

AUSTER: [laughs] I don’t really think so. I have written a lot. If you do this for so many years, the piles are bound to grow. I’ve been writing seriously ever since I was 15 or 16 years old. We’re talking about more than 50 years. It’s hard to believe.

WENDERS: You actually started when you were 15?

AUSTER: Yeah. But you’re about a year older than I am, and I can’t begin to count how many films you’ve made and how many books you’ve published. I have a big shelf of books by you.

WENDERS: I hope it’s not bending. Today movies can fit in such small spaces. I have a few of my movies on a stick. There’s your life’s work on a bloody stick.

AUSTER: I suppose you can do that with books, too. I hate reading digital books. I don’t enjoy the experience. I like smelling the paper, turning the pages. I think the book as we’ve always known it is an efficient technology.

WENDERS: I heard that Trump said even smelling a book makes him feel tired.

AUSTER: [both laugh] I don’t think he’s ever read one.

WENDERS: I want to ask you, where do you start? The most important question for me when I begin working on a film is where to start. For a book, what makes you convinced there is a story that is worthwhile?

AUSTER: Generally, I don’t want to do things. I feel lazy and unmotivated. It’s only when an idea grabs hold of me and I can’t get rid of it, when I try not to think about it and yet it’s ambushing me all the time. I’m thrown up against a wall. The idea is saying to me, “You have to pay attention to me because I am going to be the future of your life for the next year or two or five.” Then I submit. I get into it. It’s something that becomes so necessary to me that I can’t live without doing that project. That’s how it begins. A book, at the same time, also has to do with what I call a buzz in the head. It’s a certain kind of music that I start hearing. It’s the music of the language, but it’s also the music of the story. I have to live with that music for a while before I can put any words on the page. I think that’s because I have to get my body as much as my mind accustomed to the music of writing that particular book. It really is a mysterious feeling.

WENDERS: Is the setting part of that initial feeling? Are the stories connected to a specific place from the start?

AUSTER: Siri—who’s studied so much about the human mind—says that memory and the imagination are almost identical. It’s the same place in the brain and the same thing is happening. When you think about your own life, there are no memories without place. You are always situated somewhere. I think the imagination—the narrative imagination at least—situates you in a specific space when you start to think of a story. I often use places I know. I put my characters inside rooms and houses that I’m familiar with—sometimes the houses of my parents or grandparents or previous apartments I’ve lived in.

WENDERS: I’ve read all of your books, so I know all your apartments.

AUSTER: Right! In Winter Journal [2012], I listed every one of them. Even if I don’t talk about the room at any great length, I have the sense that I’m able to see the characters moving around in that specific space.

WENDERS: I have a fantastic memory for places myself. I have the most uncanny memory for hotel rooms, believe it or not. I think I can remember every hotel room I’ve ever stayed in. That is because I have no memory for lots of things—names, God knows what.

AUSTER: You’ve probably stayed in thousands of hotel rooms over the years. It’s funny because I don’t remember hotels at all. I can never even remember the names of hotels I’ve been in.

WENDERS: Has it ever happened that the idea that grabbed you is no longer of interest after sitting down and writing it for a while?

AUSTER: In all the years I’ve been writing novels, it’s happened twice. I’ve started something and gotten into it to some degree—say between 50 and 100 pages of text—and suddenly, number one, I’m no longer interested in the ideas, and, number two, I didn’t know how to do it. I simply couldn’t figure out how to tell the story correctly. There was one aborted project in which I felt the novel was spreading out on either side but I wasn’t able to drive it forward, and therefore, I felt that I was just treading water. Even though sentence by sentence it was perfectly fine, the overall effect was static and boring, and I had to abandon it. Another time—it was The Music of Chance [1990], a book I wrote in the late ’80s—I started the book in the wrong place. I started it too early in the story, if you know what I mean.

WENDERS: You wrote the prequel.

AUSTER: That’s right. [laughs] I wrote about 75 pages and realized that it was all unnecessary, that I had to start it later on. The fact that I had written all that material helped me, though, even if it was scrapped.

WENDERS: In books they don’t have deleted scenes, like with DVDs. You could have your deleted scene in a book as well!

AUSTER: There are scholarly editions of novels in which they do this. Famously, in Great Expectations, Dickens wrote two endings to the book. There was the dark ending and the happy ending.

WENDERS: I read the dark one. I sympathize with sitting down and being in the grip. But the reason I never wrote a novel is that I don’t have what it takes to write characters, so they would all be talking differently. I lack that ability. If I were writing, they would all talk like me, and that’s no good. How do you make a character that isn’t you?

AUSTER: This is where writing and acting meet. I am entering the minds of characters who are very unlike me. And I feel that I’m doing what an actor does when he or she inhabits an imaginary character. Which is why, the four times I’ve worked on movies, I’ve never had a problem talking to actors. I always felt in great harmony with them. It was after those experiences that I realized there’s a similarity between writing fiction and acting. The writer does it with the words on the page, and the actor does it with his body. The effort is the same. This is what the imagination does. You thrust yourself into people you aren’t—the unknown or the different.

WENDERS: And you stay true to them. You don’t betray them. I think that’s the most difficult part of that craft.

AUSTER: One of my books, Mr. Vertigo [1994], was narrated by an ignorant, illiterate boy in the 1920s. It was such a transformation for me to be inside that kid. But it was thrilling at the same time.

WENDERS: It was like a holiday.

AUSTER: Yes! [laughs] Say goodbye to myself for a little while, thank you very much.

WENDERS: Okay, I know once you sit down, there are many kinds of writers—hand-writers and typewriters and computer writers.

AUSTER: I’m a pen-and-paper man. I write everything by hand first—in big notebooks I get in France, because I like one particular French brand, Clairefontaine. For some reason, I’m most comfortable writing on graph paper—quadrille-lined paper with little squares. God knows why I feel most comfortable with that.

WENDERS: White or yellow?

AUSTER: White paper with faint blue squares. I write with a fountain pen mostly, sometimes with a pencil. I write paragraph by paragraph. That’s how I build a book. A paragraph to me is a unit of thought and language similar to a line in a poem. I work on a paragraph until it seems more or less finished. At that point, I’ve generally gone through it so many times that I can barely read my writing anymore, which tends to be small. After I’m done with the paragraph, I turn around and type it up on my ancient manual typewriter—a German typewriter, by the way. Olympia.

WENDERS: I know all about your Olympia. I remember that fierce competition between you and Sam Shepard to find out from the other one who was the provider of your ribbons. Sam wasn’t willing to give up his provider, and you weren’t willing to give up yours. [laughs] I was under the impression that it was a matter of life and death.

AUSTER: Well, I did find a new source, and I stocked up. I probably have enough typewriter ribbons to last me the rest of my life. I use them very sparingly. This new book was over 1,100 pages, but I used only three of four ribbons to do it. I type it up so I can look at it clean, and then I start attacking that typed version with more corrections.

WENDERS: You go paragraph by paragraph, and that is how you proceed?

AUSTER: That’s it. I’ve also found that the beginning of a book goes very slowly. It can take me two days to write the first paragraph or the first page. If I can do half a page after eight hours of work, that seems decent to me. I’m happy. But then, as I get deeper into the project, the pace accelerates. You begin to feel more comfortable in the music you’ve established. The thing is, even though I’ve written a lot of books, every project is new. I have to teach myself each time I start a new book how to do it. It’s a great adventure, a process of discovery. It’s not something I’ve mapped out in advance or have any answers to. I only find answers in doing it.

WENDERS: When you read the first paragraphs of a lot of writers, you recognize the formula. Sometimes they live with one formula, and they do good work until the end of their life. Each time I start one of your books, you’ve reinvented the process. There is no recipe for it.

AUSTER: I’m more or less lost all the time. The fact that I’ve written all these other books doesn’t help me with the new one. I feel like a beginner every time.

WENDERS: Experience is a burden. I know that feeling.

AUSTER: The only thing I feel I’ve learned over the years is what happens to me when I run into problems. With every novel, there are times when you’re going to get stuck. You’ll come to a wall. Something you thought was a good idea turns out to be a bad idea, and you’re not quite sure how to proceed after coming to that barrier. When I was younger, I would fall into great despair. I’d say to myself, “The book is done. I’m never going to be able to finish it.” And then, of course, after stewing about it for a week or two-or three or four—I’d find a solution and continue. Now, as an older person, when I come to these moments of so-called crisis, I don’t panic anymore. I say to myself, “If this book needs to be written, it’s already there somehow. I’ll find it. I just have to be patient.”

WENDERS: Are there any other writerly habits you have? Anything else you need besides a writing pad and a typewriter?

AUSTER: Not really. I think that’s pretty much it. I like silence. I don’t listen to music. To me, that’s a big distraction. I tend to get up and walk around the room a lot. I don’t sit in my chair for prolonged periods of time—no more than 15 or 20 minute stretches. Then I have to get up and walk around. In the movement, I find the rhythm I’m talking about. It’s in the body. Just moving around starts to generate words in a way that’s better than when I’m sitting at my desk.

WENDERS: Your body helps you to write.

AUSTER: Absolutely. I feel it’s a physical process.

WENDERS: I know couples that are both bakers or doctors. I’m married to a photographer. Is being married to another writer harder or different than most professions?

AUSTER: Here’s the thing: You and I both agree that Siri is not just a good writer but a genius. I think Siri is the most intelligent, brilliant person I’ve ever known. She has an incredible talent for thinking and absorbing new information, taking on new subjects, going through vast mazes of knowledge, and she has an omnivorous mind. How exciting it’s been for me to watch what she’s been doing all these years we’ve been together—almost 36 years now. I’m eight years older than Siri, which makes us contemporaries, but not quite. We are not competing. We’ve never competed. We have admired what the other is doing, supported what the other is doing, and we’ve always been each other’s first reader.

WENDERS: Oh yes?

AUSTER: I show her everything. She shows me everything. Not a page gets out of this house without it having gone through the other person’s reading. Siri is the best editor, the most astute reader. I don’t think there’s ever been a moment when I haven’t taken her advice.

WENDERS: It’s tough to be married to a genius.

AUSTER: Everyone thinks it’s a problem to be married to someone doing a similar kind of work, but on the contrary, it’s a great help. We each understand the needs of the other. We spend our days in the same house two floors apart. She’s on the top floor, and I’m on the bottom floor of our brownstone in Brooklyn. We don’t talk during the day. Right now as we speak, I’m in the living room and she’s upstairs—two stories up—working on her book. We get together afterwards in the late afternoon or early evening and start living like a normal couple. During the day, silence reigns in the house.

WENDERS: Well, if you had a dog, it’d be louder.

AUSTER: We did have a dog, a beloved dog who’s been dead now for ten years or so. Jack.

WENDERS: I remember Jack very tenderly. Jack was sort of the link between you two. He would go visit one and then the other.

AUSTER: [laughs] That’s right. Of course, we have a daughter together, too, but she was in school when we were doing this. Now she’s all grown up and living on her own.

WENDERS: You’ve switched professions a little bit in your life and made four movies. Didn’t you tell me you once considered going to film school?

AUSTER: Early on, when I was about 20, I got so interested in film that I thought I would try to go to film school in Paris, the same school you wanted to go to.

WENDERS: IDHEC [now known as La Fémis].

AUSTER: Yes. The reason I didn’t pursue it was, fundamentally, that I was so grotesquely shy at that point in my life. I had such difficulty speaking in front of a group of more than two or three people that I thought, “How can I direct a film if I can’t talk in front of others?” I gave up the idea because of my shyness. Now it’s not a problem. I think teaching probably helped me.

WENDERS: Would you consider making another movie? You did Smoke [1995], Blue in the Face [1995], Lulu on the Bridge [1998], and The Inner Life of Martin Frost [2007].

AUSTER: That last experience was a very happy one, I must say. It was made for almost no money, produced by our mutual friend Paulo Branco. We did this on a so-called shoestring budget. I had four actors, three locations. I knew everything was going to be limited. We shot in Portugal because I knew that’s where we could get the support financially. I had a wonderful time with my small crew and enjoyed the process immensely. The film, however, was a flop. It did nothing. Somehow, working for a year and a half straight on that project and to have nobody see it and to be 60 years old at the time, I thought, “Maybe I should stop doing this. I don’t have that much time left, and I’d prefer to use that time writing.” I don’t think I’m going to go back to it, but who knows? Maybe something will change my mind. I know the pleasure you get from making your films. The intense involvement in every aspect: the acting, the camera, the colors, the costumes, even the hair and makeup. Editing is thrilling. Everything to do with films is absorbing—everything but the money part, the business. But I’m deeply glad I’ve had that experience.

WENDERS: I encourage you to go for the next one, but then I realize we are both at the age where we think twice before we start something. The thought sneaks into your mind, “I can’t do a million things anymore like I could when I was younger.” You start making choices.

AUSTER: Right. If the burning idea ever did start rising up inside me and I felt I had to do it, then I’d try.

WENDERS: What is it that you like to watch? If it’s a nice night, you have nothing to do, your writing went well, you’re free to relax, there is no baseball on the television, what is it that you do?

AUSTER: In other words, how do we live our life here beyond work?

WENDERS: What’s left of our lives.

AUSTER: Exactly. The act of writing is so exhausting to me, physically and mentally. I get so tired by the end of a day that I feel as if I’ve been running in a marathon. Less and less do I spend evenings reading, especially while I’m working on a novel. Pretty much what we do every evening—when it’s not baseball season, as you mentioned—is watch a movie or two on TV. Siri and I collapse on the sofa and watch all kinds of films. Generally, we like watching old films. There’s this great television station in America called Turner Classic Movies. It’s really like having a cinematheque in your TV 24 hours a day. In the last few years, we’ve been exposed to scores of American films from the ’30s that we didn’t know about. I think there’s an energy in these Depression-era movies, a new style of acting and way of being in front of the camera that’s exhilarating. People like James Cagney or Edward G. Robinson; these were new kinds of actors. They were not beautiful people, but they had the fire of life inside them. They were so natural. In some of the early ’30s movies, you can see them improvising. They’re making things up in front of your eyes. We love watching the old stuff.

WENDERS: Both the film noirs and the comedies?

AUSTER: Yes, all kinds of things. Yesterday, we watched one of the first movies Douglas Sirk made after moving to America. It was called A Scandal in Paris [1946] with George Sanders playing [Eugène-François] Vidocq, the old French criminal turned policeman. It’s a funny, charming movie.

WENDERS: I met [Sirk]. In his old age, he taught at the film school I went to. I had left already, but I met him a couple of times. I actually met him because it was Fassbinder who was completely infatuated with him. Sirk certainly influenced us big time. He was funny and alive and interested. He was probably 80 already. He was a very pleasant man. Has there ever been a movie that inspired you to write something?

AUSTER: Absolutely, there’s no question about it. Sometimes in novels—Ghosts [1986] and Man in the Dark [2008] spring to mind—and in a recent autobiographical book, Report From the Interior [2013], there’s a section devoted to films that made a big impact on me when I was child. The first was The Incredible Shrinking Man [1957], which I saw when I was 10 years old and which utterly changed my life. It opened new ways of thinking about the universe that had never occurred to me until that moment. And then a little later, at 14, I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, a 1932 American film, which also had a tremendous impact on me politically. This film is a powerful piece of work. I’m sure you’ve seen it, right?

WENDERS: Yes. Mervyn LeRoy directed it. I loved it, all those black-and-white film noirs.

AUSTER: They’re very satisfying. Over the years, you and I have had a number of ideas for projects to work on together, but one by one they all fizzled. [laughs]

WENDERS: That’s why we are such good friends!

AUSTER: The first project we had was your idea. You said, “Let’s take the Flitcraft episode from The Maltese Falcon and turn it into a new story.” I worked on it. I wrote a treatment of about 15 or 20 pages—a story we both liked. But then the financing we were hoping for fell through. The project never developed. I had those pages sitting in my desk for years. Then, when I wrote Oracle Night [2003]—12 or 13 years later—I pulled out those pages and used them. They become the story within the story in the novel. Nothing is ever fully lost I guess.

WENDERS: It goes to show. The two of us know each other because I strolled down an avenue in Sydney in 1988 and walked past a bookstore and saw a book called In the Country of Last Things [1987]. I liked the title and the cover. I remember I kept walking and I stopped and realized I couldn’t keep going on. I walked back and acquired the book strictly because of the title. I didn’t know anything about it. I bought the book next to it as well, City of Glass, because this author has a knack for titles. Then I read one in one night and the other the next night, and that was the only letter I ever wrote to an author. I thought, “This is a man I want to meet.” And then we met.

AUSTER: It was the most beautiful letter anyone has ever sent me. You said, “I make films.” You didn’t say, “I’m the world famous Wim Wenders.” “Dear Mr. Auster, I’ve read all your books. I’m sorry there are no more to read at the moment. I make films. Maybe we could work on something together.” That was essentially your letter. Then, when we finally did meet, it was that historic day in Germany in 1990, the day of German reunification.

WENDERS: Ah yes, October 3. Reagan had been in Berlin, and I thought, “I want to get the hell out of here.” I went to Frankfurt to see you at the book fair, no?

AUSTER: That’s right. We had dinner, and it was the beginning—as Humphrey Bogart would have said—of a beautiful friendship.

WENDERS: Everybody came to Berlin that day, and I was the only one who took the flight out. It was an empty plane to Frankfurt. We’ve known each other for 26 years.

AUSTER: That’s right. Time marches on. It’s incredible. I sometimes think of you as a new friend.

WENDERS: You have such good titles. The Music of Chance, The Book of Illusions [2002], Oracle Night. Do you need the title when you start writing?

AUSTER: I can’t begin a project unless I have a title.

WENDERS: You feel relief. I also can’t think without a title.

AUSTER: I need a title. In fact, The Music of Chance was the only book I wrote in which I changed the title. I didn’t know what it was going to be. I had a provisional title taken from a beautiful piano piece by François Couperin called “The Mysterious Barricades.” I knew it was too heavy, too symbolic. I knew I wasn’t going to keep it, but I held on to it for the time being as a working title. I was about halfway into the book and I remember it was a Saturday. I was here in Brooklyn buying some food for the house, and they had that awful canned music blasting in the market, and suddenly “The Music of Chance” popped into my head. I said, “That’s the title of the book.”

WENDERS: It flew to you.

AUSTER: Also, I have to say, 4 3 2 1 had a different title to begin with, a title I would have been happy to live with, which was simply Ferguson, the name of the main character. About a year and a half into writing the book, a terrible thing happened in a town called Ferguson, Missouri, where a policeman shot and killed a young, unarmed black man. If I were to publish a book in the United States today called Ferguson, everyone would assume I was talking about that dreadful incident. So I came up with a new title, which I think I prefer in the end.

WENDERS: New York is your city. In music it was Lou Reed’s city, and in literature it’s your city. What if you had been born in Chicago?

AUSTER: I would have been a different writer. I would have written about a different place. All writers, all filmmakers are devoted to the place they know best. Places form us; it goes without saying. It’s hard to imagine myself writing about Chicago, but if I had been born in Chicago, it would seem very natural.

WENDERS: 4 3 2 1 is a very big. I myself would humbly call it your big American novel. Were you intimidated when you realized what you were up to with this one?

AUSTER: No, I wasn’t intimidated at all. I felt that I’d been preparing all my life to write this book. I’m glad I’ve lived long enough to finish. 4 3 2 1 took me three years to write. To me, that seems incredibly fast. I was overwhelmed by how the thing kept pushing along and the pages kept piling up. Of course, I didn’t do anything else—I didn’t travel, I didn’t do interviews, I didn’t do readings. I just sat in my room every day for three years and wrote. I wasn’t intimidated. I was exhilarated.

WENDERS: How did you keep all these narratives organized? Did you have a wall with little notes?

AUSTER: No, not really. It was all in my head. Once I had the idea, the book seemed to generate itself. Each chapter is like a small, separate work. I would start each new chapter with a general sense of what I wanted to put in there, but I kept finding new things as I was writing. There were also dozens of other characters and situations that I eliminated to keep it as spare as I could. I know the book is an elephant, but I hope it’s a sprinting elephant.

WENDERS: You brought your whole life as a kid into it. I guess, in many ways, it’s autobiographically inclined, but so is all writing.

AUSTER: The book does echo many things about my life, but there are very few actual autobiographical experiences in it. I can give you one. Somewhere right around the middle, when Ferguson-4 is 14 years old, he plays in a basketball game in Newark, and there’s a near race riot. That game actually happened, and we did win in triple overtime on a half-court shot at the buzzer. Nearly everyone in the gym tried to beat us up, and we had to run out of there. It was quite an experience. [Wenders laughs] There’s also a part when Ferguson-4’s friend from summer camp dies. That’s based on something that really did happen to me. It’s different in the novel—a completely different cause of death. When I was 14, I was with a group of boys at a camp, and we were on a hike. We got stuck in the woods during a terrible electric storm—very intense lightning and thunder. We were crawling single file under a barbed wire fence to get to a clearing, and when the boy directly in front of me passed under the barbed wire, lightning hit the fence and he was electrocuted—killed on the spot. I was no more than six inches away from him. That changed my life. That one moment taught me that anything can happen at any moment. This is the source of the book. The death of that boy. I’ve been haunted by this event for more than 50 years.

WENDERS: Isn’t that the thing about fiction? It’s a way to protect and preserve these things better than with a nonfictional context. I sometimes feel fiction is the ideal preservation for real memories. Fiction is such a good place to keep things.

AUSTER: Yes. I agree because it lives on most vividly in the mind of the reader. Once you finish a book, it doesn’t belong to you anymore. You’re giving it to other people. If something in what a writer writes can excite the imagination and the feelings of the reader, then that reader carries it around forever. Nothing is more vivid than good fiction.

WENDERS: I’m so glad we got this chance to talk. We have been friends for so long.

AUSTER: Yes. I was thinking about those famous last words supposedly said by Goethe on his deathbed, “More light!” “Mehr Licht!” What he should have said was, “More life.”

WENDERS: [laughs] It’s highly debatable if that’s what he really said. But, yes, that is what he should have said.

AUSTER: Yes, for the both of us: more life.

WIM WENDERS IS AN AWARD-WINNING FILMMAKER, WHOSE UPCOMING FILM, SUBMERGENCE, FEATURES ALICIA VIKANDER AND JAMES McAVOY.