theater

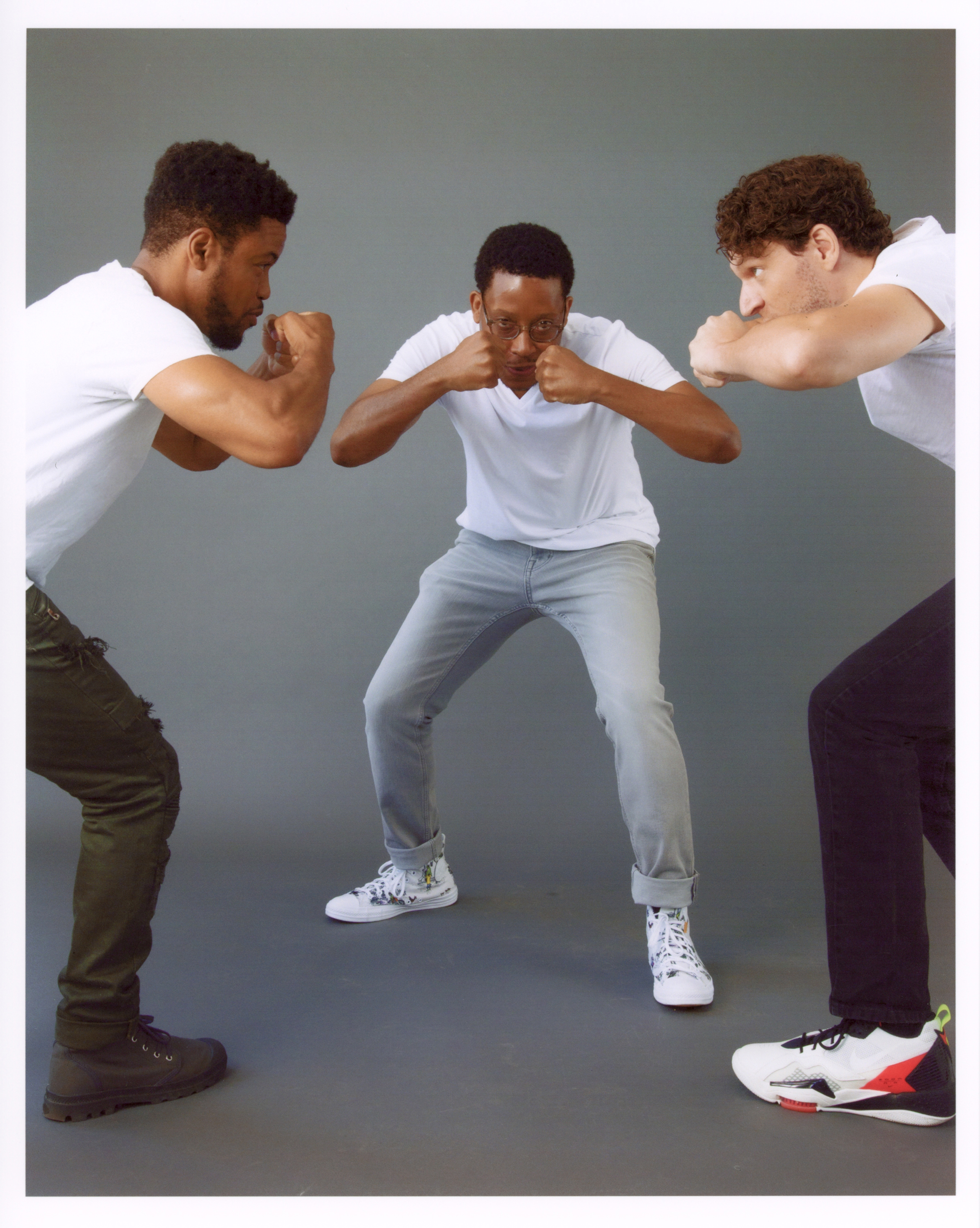

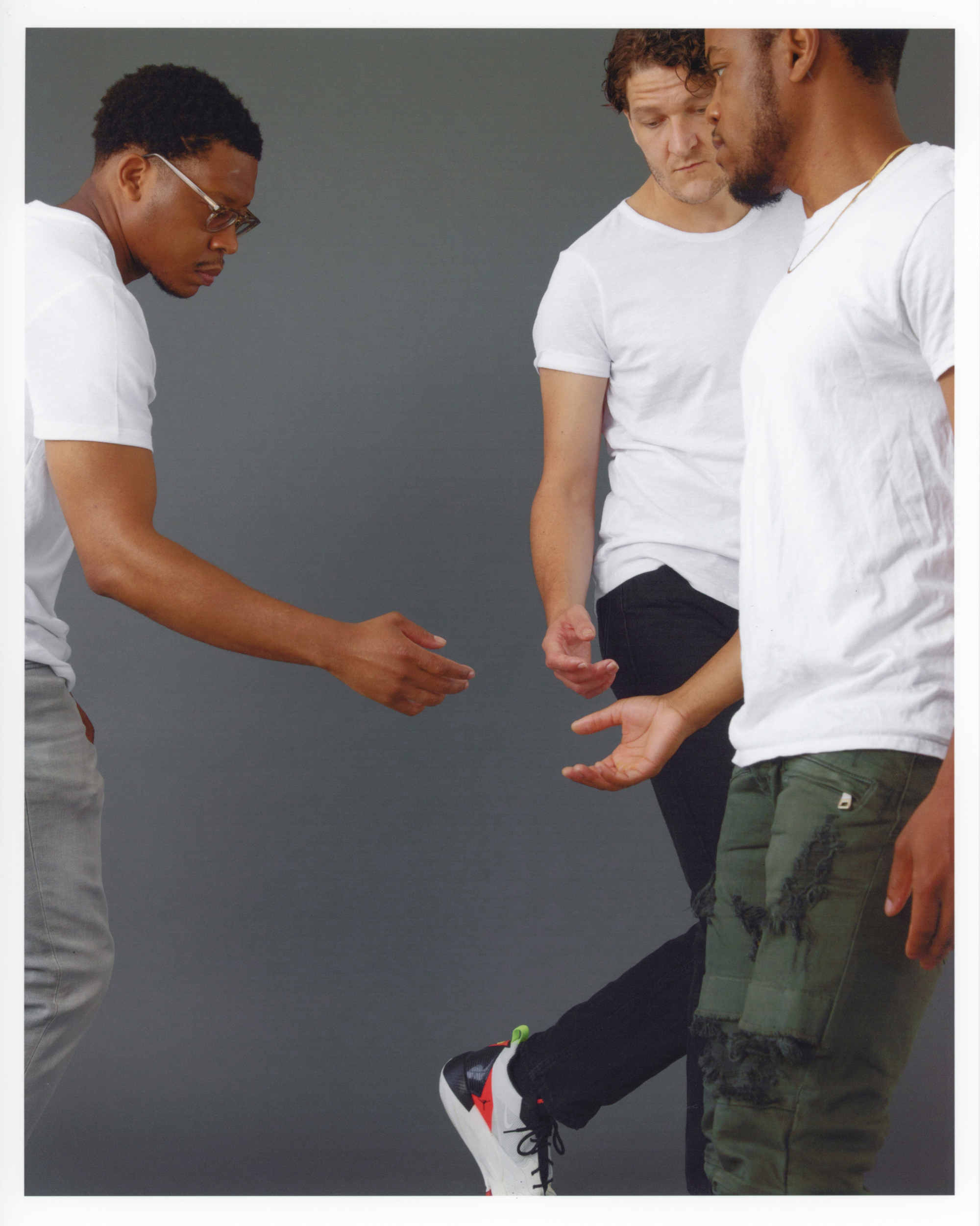

Pass Over Is the Play Leading Broadway Out of Darkness

Art is referred to as timely when it reflects and refracts the issues of the day. But in Antoinette Nwandu’s play Pass Over, timeliness is the message. Premiering at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater Company in 2017 (Spike Lee filmed an early performance and adapted it into a 2018 film), the story is anchored in the relationship between Moses and Kitch, two Black men played in the original production by Jon Michael Hill and Namir Smallwood, who are trapped in the stasis of America’s systemic police violence and the threat it poses to Black life. For the duration of the roughly 85-minute play, the old friends idle on an unnamed street corner, talking freely as an ambient dread lingers and grows. That feeling is justified when a white police officer, originally played by Gabriel Ebert, arrives on the scene.

Drawing from Samuel Beckett’s existentialist masterpiece Waiting for Godot and the Book of Exodus, Nwandu toggles the play’s tone between nihilism and optimism. The dialogue eschews punctuation. Instead, Nwandu relies on line breaks in a way that “leans into the poetry and the jazz of how Black people talk,” says Smallwood. Moses and Kitch repeatedly play “Promised Land Top Ten,” where they fantasize about what they’ll get when they “pass over” to paradise (buttery lobster rolls, a drawer of clean socks). Later, their conversation is cut short by gunfire, and they instinctively drop to the floor. They don’t seek death, but life on the block has prepared them for it.

Earlier this month, Pass Over became the first play to return to Broadway when it began a nine-week run at the August Wilson Theatre featuring the original cast, as well as the director Danya Taymor. And while Nwandu was partially inspired to write Pass Over following the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin, in the wake of last year’s global reckoning with police brutality she felt the time was right to tweak the play’s original ending, which featured the death of a major character. “Danya and Antoinette wanted to keep it in conversation with the world around us,” Hill explains. “It would have to change because our world has changed after some upheaval.”

“We’re going to try to bring the consciousness and awareness of everything that happened in 2020 into the room,” Ebert says. But the changes won’t alter the show’s essence. “They are still under assault for the duration of the play,” Hill says. “So they have to find a way to deal with the threat of death, which is something that underprivileged communities have to deal with and that people are just now starting to realize.” For the cast, this revised, hopeful ending is a blessing. A chance, says Smallwood, “to explore what the other side of freedom can be.”

———

Grooming: Rochelle Walker

Photo Assistant: John Novotny