Novelist Dennis Cooper thinks the kids are alright

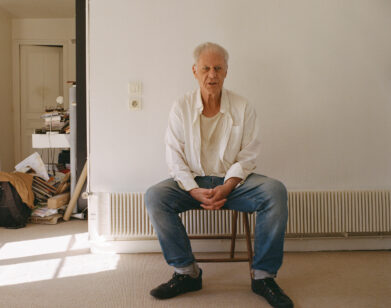

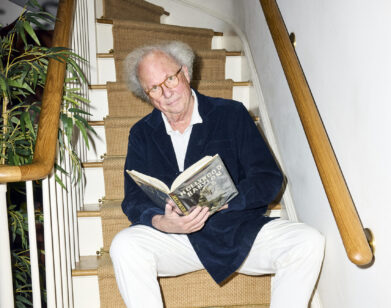

DENNIS COOPER, LEFT, WITH COLLABORATOR ZAC FARLEY

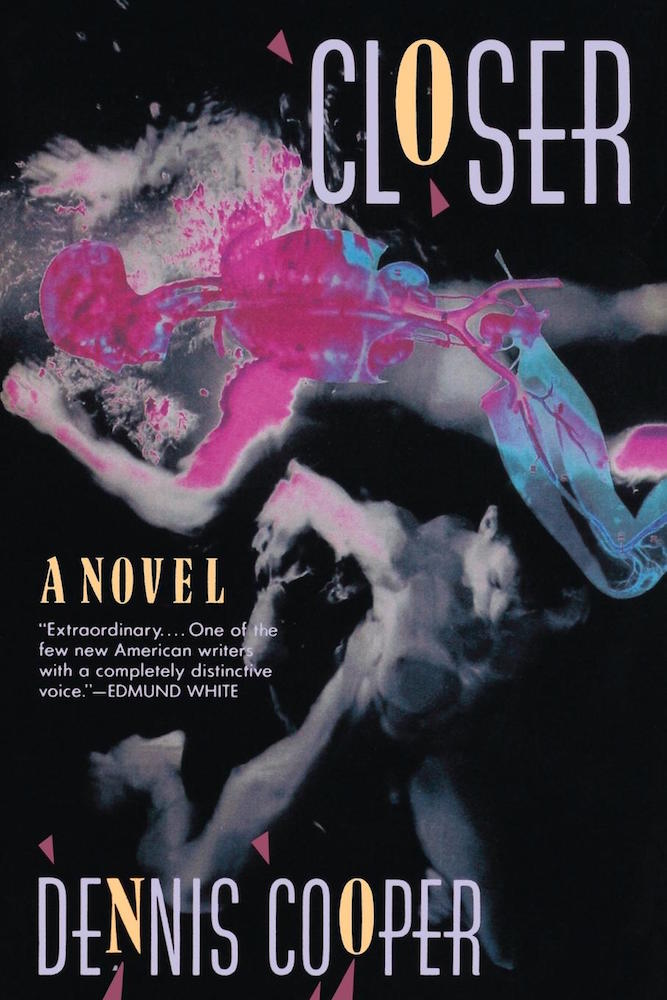

The first Dennis Cooper novel I read was The Sluts [2007], his chronicle of a young male prostitute’s brutal life as told through comments on an online message board. Unfortunately for the author, I couldn’t put the book down, and finished it right there in the store without buying it. Fortunately for him, I bought three more of his books on the spot.

Cooper’s literary legacy began with the George Miles cycle, a series of five books published between 1989 and 2000 that revolve around an alluring, passive young man who sparks overwhelming emotions in the people he meets. The fictional Miles is modeled off a real person of the same name, who Cooper befriended in ninth grade, and had a brief affair with more than a decade later.

Early readers were shocked by Cooper’s unblinking portrayals of deviancy. Pedophiles, necrophiles, cannibals, drug addicts, and various combinations of the above lurk throughout his books. But Cooper didn’t become one of his generation’s most essential voices just by depicting extreme behavior. Rather, it’s because he twists cruel and delicate things together into an incandescent lattice, tracing sadism and teen angst with the same tender brush. He’s drawn to the nuclear isotope of obsession that fuels them both. A typical Cooper protagonist might escape from a snuff filmmaker’s dungeon only to spend the rest of his day arguing with friends about bands, or sulking in his room over a crush.

Cooper has never limited himself to fiction. For one thing, he’s a relentless blogger: his website, updated daily, catalogs his vast array of interests, from experimental film and literature to detailed updates on new theme park rides and round-ups of young men advertising themselves as slaves on fetish sites. Cooper is also a prolific critic, poet, and even a modern dance composer.

Most recently, he’s turned to the screen, collaborating with the visual artist Zac Farley on a movie titled Like Cattle Towards Glow [2015]. “Dennis and I met about six years ago and became friends,” recalls Farley over email. “We’re pretty like-minded and have neighboring sets of interests in theme parks, literature, and art. We’re both attached to creating an access to incommunicable and confused emotions—particularly in teenagers.”

Now, the pair have released a stunning new film titled Permanent Green Light [2018], about a disabled French teen named Roman, and his attempts to disappear completely by blowing himself up. Roman and his friends float through their blank suburban town, living messily and dying gracefully. They project totemic meaning onto suicide vests, pinatas, and minimalist electronic music. The film’s dream logic “presents a world and a set of characters that appear wholly realistic,” Farley explains, “but whose freedom to digress in their feelings, imaginative leaps, and actions is as otherworldly as science-fiction.”

Cooper grew up in California, and has spent much of his life there. Several years ago he moved to Paris, but he still keeps an apartment in Los Angeles. That’s where I caught up with him over the phone a few weeks ago, as he prepared to catch a flight around the world.

MARCUS: How are you doing?

COOPER: Okay, I have to fly back to Paris today so I’m a little, pre-flight, whatever that thing that happens to you when you have to take a flight.

MARCUS: Yeah, a mixture of fear and revulsion.

COOPER: It’s like dread of the jet lag, because it’s 9 hours and the jet lag is horrible, so it’s mostly about that.

MARCUS: What’s up with you living in both Paris and Los Angeles?

COOPER: I’m mostly in Paris, I’m there like 90 percent of the time. I still have my place here so I come back here once in a while or when there’s a reason to, but mostly I live in Paris.

MARCUS: So why did you decide to start making movies?

COOPER: My collaborator, Zac Farley, we met six years ago and we had this really similar sensibility and so we started doing projects together right away, different kinds of projects. And then the opportunity came to make the first film and it was so do-it-yourself, like $40,000 dollars to make the whole film and everything, and we thought, let’s just do it. We just liked doing it so much that we decided to make a real film, and we got a producer, and now making films with him is sort of the main thing I’m doing. I’ve always really loved films, I just didn’t ever have the equipment or talent to do a film by myself.

MARCUS: Are there limitations that you start to feel with literature after a while, that aren’t there when it comes to making a film or writing a script?

COOPER: They’re really, really, really different. I just felt like I got sick of writing, I mean I still write, but it’s very different to write a book because everything in the entire book is in the script, in the text. The text creates images in the head, and then readers make the movie and see all the visuals and decide what everyone looks like and what everything looks like. But it’s really different to write something where it’s going to be visualized, where people are going to know what the characters look like, they’re going to know what the places look like. It’s really different which is what’s exciting about it, because you give up a lot of control in a way, and also the viewer doesn’t have as much room to move. The viewer has to take what’s there and work with what’s there. It’s super exciting to work in this way where I don’t have to create every tiny detail of what’s going to happen.

MARCUS: How involved are you in framing the shots and the cinematography?

COOPER: That’s Zac’s strong suit and writing is one of my strong suits. Everything is completely collaborative. He generally has a sense in his head of how to visualize it, but we talk about everything and I’ll tell him my ideas. Before the actual shooting, it’s collaborative but with him being the boss, because he’s better at it than I am. But when we actually shoot it, I’m there and I’m working on the set and everything.

MARCUS: I was thinking about the character Roman, he shares certain similarities with other central figures from your books, like George Miles. On the one hand, he’s similar because he has these mysterious motivations, and his friends are in love with him, but he’s a bit more driven and active than Miles, who’s generally passive. What were you thinking about when you put this character together?

COOPER: Yeah, I can see that. The things that make him similar to those other characters are things that I don’t think about, they’re just there because I’m interested in that kind of character. I was thinking more about the differences. Yeah, he’s not passive and I don’t think he cares what other people think, whereas generally with the other characters, they’re entirely driven by wanting to be loved, or wanting people to be attracted to them. I think emotionally he’s very similar in the way he’s discreet about his feelings, and also the way he’s sympathetic, but also we tried very hard not to make him too sympathetic. We didn’t want people to actually care that he killed himself. He’s an archetypal character, that I’m interested in, but if you take out physical attraction, it’s actually pretty different. I don’t think his friends are attracted to him. They think he’s fascinating, or strange, and they’re excited that he could perform this ultimate magic trick.

MARCUS: I’m out on a limb here, but I feel like the politically detached, neutral way of thinking about terrorism in this film seems more French than the typical Fox News, American way of thinking about it.

COOPER: [laughs] Yeah, the terrorism thing is pretty buried. The original inspiration was this kid who was a suicide bomber named Jake Bilardi, he was an Australian kid who ended up joining ISIS. He was in the news and stuff and no one could ever figure out why he did it. There was nothing in his past or in his interests that would make you think he’d join ISIS. He wasn’t religious and he wasn’t political or anything; so the idea that Jake Bilardi did it because he wanted to disappear, he wanted to find this thing that was so huge, had so much meaning that he could just disappear into it, was the inspiration for [Roman]. We aren’t really interested in terrorism; It’s really more about how he wants to be the ultimate magician, and given that he’s not a wealthy boy and he lives in a strange place, he just ends up deciding this is the only way that he could do it given the means he has at his disposal.

MARCUS: One other thing I loved about the film was the strange blank suburban setting. What is this area?

COOPER: It’s Cherbourg, it’s a city on the sea, on the ocean. Cherbourg’s entire identity is wrapped up in being an ocean town, but we erased the ocean from the film so it would have no identity. We were really taken with how empty and depressing but interesting-looking it was. It was this town that existed because of the ocean, that’s all it’s known for, and [we took] the ocean away so that it’s this thing that has no reason for existing.

MARCUS:What is directing actors like for you? It’s so different from writing, obviously.

COOPER: Well,we didn’t want acting. We basically told them not to act. We wanted this deep performance where they exposed as little as possible and then we would find it in their eyes and their faces. It’s extremely interesting collaborating and working with other people when you’re just used to sitting at a desk and writing a book, so I really loved it. And when we shot the film we all lived together in this army base, so we were around each other 24 hours a day.

MARCUS: I love this symmetry in the film between the kid who’s fascinated by unbroken pinatas and then the girl obsessed with unexploded suicide vests. I’m curious what those represented to you. To me it seems like a metaphor for the potential energy of youth, but maybe I’m totally wrong.

COOPER: I see what you mean. I didn’t think about that whatsoever. [laughs] This is all really formal to me and Zac. The connection—he doesn’t want to break his pinatas, the girl doesn’t want to explode her vest—it was more connected to Benjamin wanting to disappear without dying. He wanted his body to be nothing and to disappear and there’d be nothing left. I see what you mean, but I didn’t think about it in those grand terms at all.

MARCUS: Another scene I loved was the one in the club, where the kid is dancing to a strange dance track. So much of your early work focuses on punk and rock; but do you think the electronic scene is now where the transgressive energy is at in music?

COOPER: I only listen to experimental electronic music now. We took this track that’s impossible to dance to, it’s this really harsh, arrhythmic track, and then we had to make our actor figure out how to dance to it. [laughs] You go to this club and they play this song that you couldn’t possibly dance to and he’s the only one dancing, and he somehow wants to figure out a way to connect to that music and make something physical of it.

Personally, I’m not interested in what’s going on in rock right now, at all. It’s very rare that I hear something that’s interesting. It seems like it’s gotten really stuck. It’s an underground thing because it’s very difficult for anything to happen now without it going viral, but this music doesn’t really go viral. It’s still a cult thing. So I suppose if there’s an underground, it’s probably that scene, people like Puce Mary and Yves Tumor.

MARCUS: You’ve been thinking deeply about the teenage experience for so many years. Obviously there’s core elements of that which are never going to change. But when you look at the lives of young people today, what are some things you feel are exciting or depressing as compared to 20, 30 years ago?

COOPER: I don’t think it’s that different. The obvious thing is the Internet and social media, but I don’t know, it doesn’t seem really very different to me. I think the social media thing, that there’s a place to expose who you are in this private way but public way, that’s really different. You can actually be a complete weirdo and find people that’ll like you. Where, before, it was a very private thing. Everything is public now. So the things that happened in my older books would just be implausible now, because those things would immediately be seen, heard about, judged, reported, talked about. But I don’t know, it’s a funny time. I was really thrilled by what happened with the Parkland kids. I really hate how people don’t respect teenagers, that’s been one of my main things my whole life. Especially lately, there’s this idea that all they do is look at their cellphones, and they don’t care about anything, and they don’t have a real life and they’re hypnotized by the Internet. To see kids who are incredibly articulate and incredibly smart and driven, thats been really exciting, because it presents this alternate image of what teenagers are like. I have a lot of friends who are younger and I don’t really sense much difference, it’s just the utilities they use.

MARCUS: So, I love your blog.

COOPER: Thank you.

MARCUS: You’ve always been fascinated by the Internet and the way that people exist on it, and I think some people might argue that the Internet nowadays is a more sanitized than it once was, especially with regard to the message board culture you wrote about in The Sluts. Your blog also feels like a throwback to an earlier, wilder era of the Internet. [Cooper laughs] I’m curious what you think?

COOPER: Yeah, I mean I started it 15 years ago [laughs] and I’m doggedly sticking to the same sort of thing I did then. In a way, the blog is a really archaic thing also because it demands so much time, each post is really long and involved and it’s a lot to look at, and you only have one day to look at it before you get something new. All of that is very much against how the Internet works and I like that about it. It’s this weird project that wants to do this one thing, and people either come or they don’t. I do those escort and slave posts, I mean, there are enclaves where that stuff still goes on. Those are all real things, it’s just that they’re much more hidden, they’re all subscription sites and they’re much more difficult to access. But the kind of thing in The Sluts, that site doesn’t exist anymore but sites that are similar are still there.

MARCUS: That’s fascinating, because when I read The Sluts I was struck, like wow, I don’t know where I’d go online to see anything this crazy.

COOPER: Well, I did exaggerate. [laughs] But there are some slave sites that are pretty intense, I have to say. It’s all fantasy, but they really go out there with their fantasies and what they’re asking for.

MARCUS: That’s all the questions I prepared, but I was wondering—Interview does these quick questionnaires comprised of questions from the the writings of Andy Warhol. Can I ask you a couple?

COOPER: Sure.

MARCUS: Okay, do you dream?

COOPER: I never remember my dreams ever.

MARCUS: Are you a good cook? And if so, what’s your speciality?

COOPER: No, I just put stuff in the microwave.

MARCUS: Showers or baths?

COOPER: Showers.

MARCUS: Is there anything you regret not doing?

COOPER: I can think of millions of them. [laughs] This is a boring answer but when I was 15 or 14 or something, my parents were driving down the Sunset Strip and I looked up on the marquee of this club and the Velvet Underground and Nico were playing there that night. I didn’t go and I always have regretted it.

MARCUS: What’s the craziest thing a fan has ever sent you?

COOPER: I don’t get those so much anymore, but I used to get a lot of boys sending me naked pictures with fake blood all over them. “Kill me, kill me,” you know. Whatever. [laughs]

MARCUS: What are you reading right now?

COOPER: I am reading two things. I’m reading Duncan Hannah’s book about his life in the ’70s and ’80s in New York, his memoir. And I am reading a book by this new experimental writer called New Juche. I really like his writing and he has a new book. Phillip Best, he was in [legendary power electronics band] Whitehouse, he has a publishing press.

MARCUS: What do you think about love?

COOPER: Oh, I think it’s the best. But I’m not sure, I sometimes think friendship love is the best, more than romantic love.

MARCUS: Why do you say that?

COOPER: You get more freedom? It’s more trust and respect and you have to give other people room, and you have to have confidence and trust. I like that you would not attach yourself to someone, and become dependent on them.