The Accidental Objectivist: Nick Gaetano

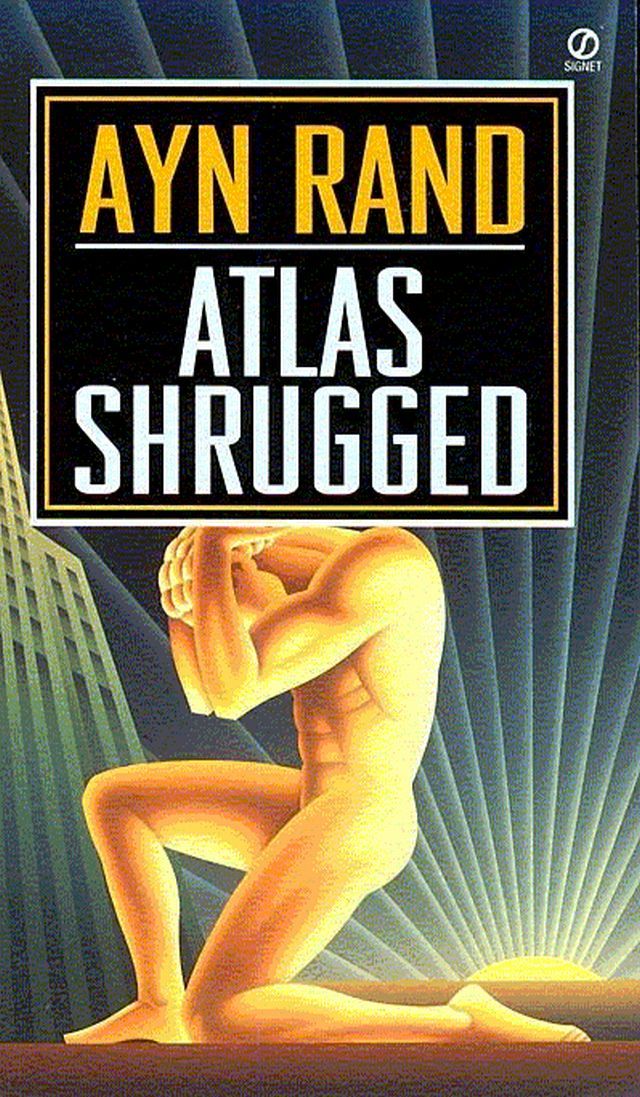

In 1981, a commission to design the 25th anniversary cover of Russian-born novelist and pop philosopher Ayn Rand’s collected works—10 books in all—was a welcome commission for the 37-year-old artist and illustrator Nick Gaetano. He had no idea that his illustrations, bold, heroic art-deco figures and images, would transcend mere covers, that they would forever intertwine Rand’s ideologies and his own.

The Laguna Beach-based Gaetano is also an award-winning artist, illustrator, and photographer whose work is in the collections of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian. He’s created covers for F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tom Wolfe, Dominick Dunne, H. P. Lovecraft, Agatha Christie, among many others. As an illustrator, he is best known for his distinctive Art Deco style, but Gaetano’s paintings tend toward the abstract. Cy Twombly is a recognizable influence. A recent series features fluid spills of black paint on plastic sheets. Gaetano has exhibited widely, most recently at Roberts & Tilton and the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art.

As Gaetano’s nephew, I’ve known his work far longer than I’ve known Rand’s. When I was young, what awed me about my uncle was how art pervaded every aspect of his life, from his spiky blue hair to his airy house to the musique concrète he listened to while he worked. His world could scarcely have been more different from Rand’s ideal of coldly rational Objectivism, and indeed from my own straitlaced side of the family. Yet, over the years I’ve come across countless Ayn Rand devotees who have spoken of Nick Gaetano and his artwork as powerful extensions of Rand’s philosophy.

How could it be, I wondered, that my uncle’s uncompromising life as an artist could translate into Rand’s uncompromising passion for ideology? How did he manage, despite the chasm between them, to craft the perfect visual complement for her work?

CHRISTOPHER HEBERT: Could you start by discussing how you came to be involved with Ayn Rand and her books?

NICK GAETANO: The books were all published by Penguin, and the art director there was George Cornell. I had worked with him on a lot of projects; we’d just finished up a series of astrology books. We had a good working relationship, and he said he had this new project, and would I be interested. The only thing I knew about Ayn Rand at the time was The Fountainhead, because I’d seen the movie. And I liked the film because I liked Gary Cooper. So I said, sure.

HEBERT: But you hadn’t read any of the books. Did you read them once you got the commission?

GAETANO: Usually when you do a cover, either you talk to the art director on the phone and they give you some idea of what the book is about, or they give you a synopsis—maybe three or four pages. With this project, I wasn’t dealing with just the publisher; the Ayn Rand Institute was also involved, and they insisted that I read all the books.

HEBERT: What did you think of them?

GAETANO: I liked The Fountainhead. I liked Anthem. I liked We The Living. I liked one or two of the stories in Early Ayn Rand. There were parts of Atlas Shrugged that I liked, but it’s three or four times longer than it needs to be. When we got into things like Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal and Philosophy: Who Needs It I was just bored—it was just the same things re-said in different ways.

HEBERT: People have very strong reactions to her books. She’s a champion of laissez-faire capitalism, a committed opponent of collectivism and the state. She had strong ideas about everything from art to religion to homosexuality, and a lot of people see her books as vehicles for these ideas, particularly because her characters deliver speeches about them. For some people, this seems to be what makes her work so powerful; for others, it’s what makes the books repellent. What did you make of her philosophy?

GAETANO: I had friends who were anarchists that liked her work. When I read The Fountainhead, I didn’t see it as pro-capitalism; I thought it was against capitalism, because the people that were involved in destroying Howard Roark’s dream were all rich, greedy bastards. I was more involved with the personalities of the people in the books than I was in the ideas. Rand was really anti-communist, but that made sense, because she was from Russia and she’d had a really hard time there. I was sympathetic to that. And capitalism wasn’t as vile then as it is today—partly, I guess, because I wasn’t really aware of what was going on.

HEBERT: So, you’re saying you were even able to read into The Fountainhead your own ideas, even though they were contrary to hers?

GAETANO: Exactly. And then I happened to read a review in the New York Times about how Ayn Rand would have had the brown shirts marching down Fifth Avenue—that she was a fascist. It was a surprise to me, because I never saw that.

HEBERT: What makes the Ayn Rand covers stand out so is the distinctive, bold Art Deco figures. You really succeeded in creating a signature brand identity; there’s no mistaking them for belonging anywhere but on her books. Did the art director or the Ayn Rand Institute present you with an idea of what they wanted?

GAETANO: Not at all. It came from my interest in Art Deco. I love that kind of design—that heroic, idealized body and structure. I didn’t want to do the books with a cover that was just the story in the books. I wanted them to be more symbolic. What I liked about The Fountainhead was the character Howard Roark, an architect who was inspired and had imagination—an idea, a vision. The people in my life that I have the most respect for are artists, musicians, film directors, writers—people with vision. To me, that’s heroic. That’s what I wanted the covers to convey. I started out with Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead; these guys are naked and statuesque, like Greek gods. I meant for them to be icons.

HEBERT: Which is exactly what they’ve become. And it seems Rand herself had something similar in mind. She wrote of The Fountainhead, for instance, as being “stylized to a heroic scale.” She never meant for her characters to be “average people” or especially human. She felt normal human failings would have made them “unreal, false—silly.” But when you say you meant for them to be icons, they were icons of things you saw in the books, not necessarily the icons Rand intended?

GAETANO: Totally. I saw the Fountainhead as idealistic, not capitalistic. I saw the capitalists as the enemy. My heroic figure was a guy who had a vision and the strength to make it real. For Atlas Shrugged, I just picked the figure of Atlas as a reference and made him heroic—an image that symbolized ideals in a general way.

I didn’t think about Rand when I did the work. I just tried to make covers that had strength for me, not her.

HEBERT: One of the things that seems to draws people to Ayn Rand is her fierceness, her moral toughness, the strength of her convictions, the clarity of her views. Do you think they see that strength and toughness and clarify in your designs as well?

GAETANO: What I liked about Art Deco was playing with shapes—making strong shapes and putting them together, making it graphic and clear and almost architectural. I don’t like fussy shit. So maybe that worked for these books in a way that was more connected to the reader than I realized or planned.

HEBERT: So, just as readers see in the books the things they want to see, they do the same when they look at your covers?

GAETANO: I see heroism as creative. I know that capitalism is their church, but I don’t know what their vision of heroism is. When you get a project like this, you have to try to distill some kind of visual direction that gives meaning to the cover.

HEBERT: Ayn Rand had particular ideas about aesthetics, too. She was a believer in romantic realism—art in which everything is warm and positive and beautiful and there’s never a note of disharmony. She felt such art made life “more beautiful and interesting than it actually is, yet give[s] it all the reality, and even a more convincing reality than that of our everyday existence. Life, not as it is, but as it could be and should be.” Do you feel like your design aesthetic was a good match for the content of the books?

GAETANO: I thought her aesthetic ideas where shit—appalling. They amounted to state art. Freedom was fine in commerce, but art had to meet her criteria.

HEBERT: There’s a website about objectivist art that has an entry on you. It discusses you and your work in the context of objectivism and the degree to which your work is or is not purely objectivist.

GAETANO: And what do they think?

HEBERT: It says your “Art Deco-influenced works are the only pieces that can be said to contain objectivist ideas. This consists mainly of sharp edges and an attempt at a positive portrayal of humanity rendered with bold colors.” In general, though, the entry isn’t very flattering. For instance, it says “the lack of solid principles held by The Fountainhead‘s Peter Keating and the same lack of solid principles held by Nick Gaetano are embarrassingly similar.” You’re also criticized here for inaccurately depicting anatomy. “For instance the abdomen muscles on the figure from the cover of The Romantic Manifesto. This is either a failure to learn anatomy, or worse, disregarding the knowledge in lieu of incorrectness with the belief that incorrectness is somehow better than correctness.”

GAETANO: I would totally agree with that: incorrectness is better than correctness. I knew that Ayn Rand would hate my work. She hated anything abstract and not literal. I’m totally the opposite. If her ideas had influenced the covers, I never would have been picked. She would have insisted on romantic realism.

HEBERT: In the late ’90s, the United States Postal Service commissioned you to create a stamp to commemorate Ayn Rand as part of their Literary Arts stamp series. I read an interview with one of the guys who gave you that commission. He tells the story of seeing some of your artwork in an in-flight magazine, and that was when they decided you would be perfect for the Rand stamp. What’s especially fascinating is that he says they had no idea you’d done the illustrations for the books. That means they’d independently come to the same conclusion as a lot of other people—that your aesthetics were perfect for Ayn Rand. The guy, Terry McCaffrey, is quoted as saying, “Rand’s family later told us that they would not have had accepted any other illustrator because they felt Gaetano embodied Rand’s aesthetics and philosophy.”

GAETANO: Weird. Over the years, just about every comment I’ve gotten is how much her readers love the covers and how perfect they are for the books. There’s a guy who emailed me last week—he’s buying my cover on his books. He’s not buying any of the new ones that are out now—he’s actually looking for my covers. When the new ones first came out, I got a lot of emails from people that were just outraged. And that’s nice; I’m happy it worked out that way, but she and the cover art are not very important to me.

HEBERT: As an artist, you probably dream of that kind of connection—to have people really drawn to your work; to have it really resonate. As a writer I certainly do. But is it strange that something that means so little to you means so much to other people?

GAETANO: I’m not really an illustrator anymore, but when I was it was cool to see my books at Barnes & Noble, my illustrations on Time magazine or in the New York Times. I did a few movie posters that I really liked. I did Blow Up and Tron; it was great to see them. I did one for Lee Marvin’s Point Blank that was painted on Broadway, maybe eleven stories high. I thought it was really cool. I agree with you about having people drawn to my work. I like it, but the Rand books are work that I’m not really involved with, so it’s sort of distant. I’ve done a lot of work I really liked, and a lot of work that was just work and is better forgotten. If people were as connected to my paintings, I’d be really happy. Then I could just keep making more. The Ayn Rand people like my work because they are part of her church. I’m not into religion.

HEBERT: You said that when you were first doing these you weren’t politically inclined one way or the other. But in the years since, you’ve gotten much more outspoken in ways that mostly don’t align with Ayn Rand. You see yourself as a libertarian, but very much on the left. Are fans disappointed when you tell them you’re not an objectivist?

GAETANO: Yeah. They all expect me to be one of them and it’s weird. I have a few friends on Facebook; they’re my friends because they love Ayn Rand, and they expect me to be this thing that they are politically. There’s a guy in LA that invited me to a party on greed.

HEBERT: A party on greed?

GAETANO: Yeah, I think they were also going to show a film about Milton Friedman, the economist who talked about how greed is really good. I’m like, oh sure, I mean, I’m really gonna go to that!

HEBERT: Did you ever respond to him and tell him what your politics actually are?

GAETANO: He knows from what I post that my politics are totally opposed to his. To me it’s very obvious how flawed capitalism is and how vile greed is. Ayn Rand’s sacred capitalism is creating a police state. I suppose she would be happy about that. It’s really the same as communism: power rests in the hands of very few. This is what I think, but her fans don’t see who I really am; they just love what I did for Ayn Rand. I’m like an actor that plays a character in a movie and then is stuck being that character forever. That’s the thing that I don’t understand the most: why they just assume because I did the covers that I’m one of them—that I believe everything they believe. It’s just crazy to me. I’ve never been able to figure it out. I’ve done a lot of book covers, but I never had people so sure I was one of them.

HEBERT: What’s the weirdest response you ever got?

GAETANO: I think in maybe 1998, I got a call from a guy in San Francisco. He had seen Atlas in an airport bookstore, bought it, and wanted me to design a Statue of Responsibility for San Francisco Bay. He had a site picked out. I spent weeks working on a digital painting and did a clay maquette; he flew me to San Francisco and New York; we had a big dinner in New York to raise money for the statue. That’s as far as it went. I’ve also had a few emails from guys asking me if they can do Atlas as a tattoo. Another guy wanted me to do a painting of Ayn Rand on his boat.

HEBERT: And then of course there’s the Atlas Shrugged feature film, which was just released on video. Did you have any involvement in that?

GAETANO: They contacted the gallery in Napa that sells my Ayn Rand prints. They were talking to them about using my work for the film and apparently it went on quite a while. I don’t know what happened or why they decided not to, but they didn’t.

HEBERT: But have you seen any of the promotional images? The film poster, for instance, of the iconic, heroic, glowing Atlas? It’s pretty reminiscent of yours.

GAETANO: It’s pretty shitty. They might have been just too cheap to redo it. It was a low budget deal.

HEBERT: You still sell prints of the cover designs. I also saw that the original paintings, which you sold in the ’80s, were resold in 2002 for a pretty hefty price.

GAETANO: I sold the originals to two guys, one in California and one from Santa Fe. The California guy bought Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead and maybe one or two others. The other guy bought everything else. I sold them all for about $5,000 apiece. Then the guy in LA sold what he had in an auction for $118,000. I didn’t get a penny of that.

HEBERT: Who are some of the writers you love?

GAETANO: When I was in my twenties, it was the great Russian writers. Later, writers like D.T. Suzuki and William S. Burroughs; Henry Miller is awesome. Alan Watts, James Joyce. Words can be fucking amazing: words can be fire; words can be ice. But Ayn Rand never moved me; not one inch.

HEBERT: Did you ever hear about the survey the Library of Congress and the Book of the Month Club conducted in 1991, asking which books have made the most difference in peoples’ lives?

GAETANO: No.

HEBERT: The Bible came in first, naturally. Atlas Shrugged came in second.

GAETANO: After I did the stamp, I did a phone interview with a guy from Australia. He was an Ayn Rand fan, and it was amazing to me the things this guy could quote. I’ve talked to other people, like the Ayn Rand Institute people, that could quote pages from her books—it’s just completely insane to me. To them it’s reading the Bible. I’m totally impressed on the one hand that people are that passionate about it, and on the other it’s totally fucked up.

Christopher Hebert is the author of the novel The Boiling Season.