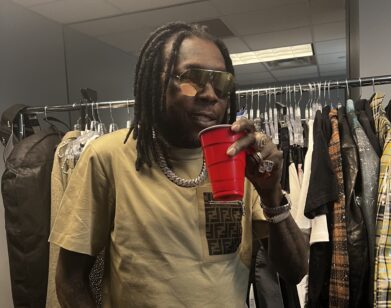

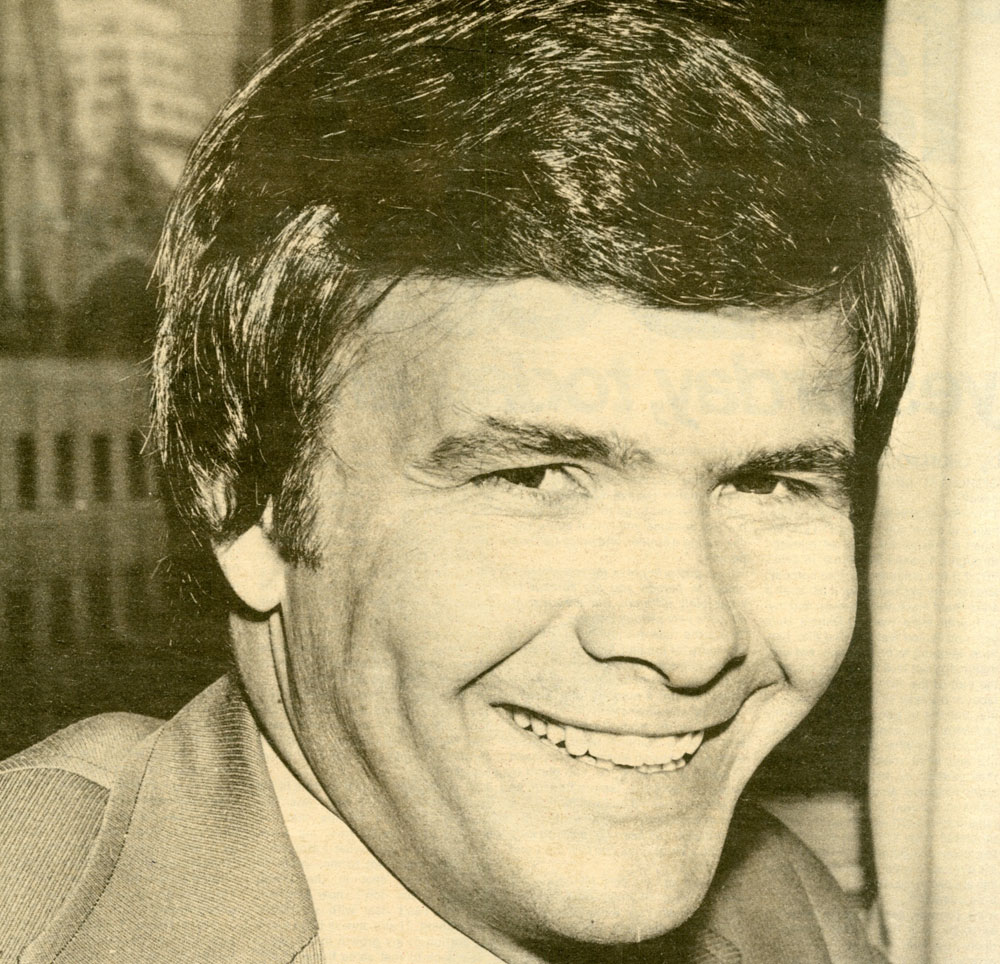

New Again: Tom Brokaw

One of America’s most trusted, recognizable newsmen, Tom Brokaw, famously ended his 22-year run hosting NBC Nightly News in 2004 with an understated, “I’ll see you along the way.” Last week, he released a memoir, A Lucky Life Interrupted: A Memoir of Hope. In the book, Brokaw details his experience from the moment he was diagnosed with blood cancer three years ago through the recovery process that followed. Brokaw, now 75, also delves into historic events he reported on over the years: the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, and Watergate, just to name a few. In honor of the release of the journalist’s memoir—and the many years he has spent broadcasting from New York’s studios to America’s living rooms—we decided to revisit an Interview article from 1976, the year Brokaw began hosting The Today Show on NBC, which he would continue for the next five years. —Haley Weiss

Tom Brokaw Today!

By Gale Lopez

On Monday, August 30th, Tom Brokaw began his new job as host of America’s oldest wake-up program, The Today Show. I met with him at NBC, Rockefeller Plaza in New York on Thursday, September 2nd. Tom Brokaw was sitting behind his desk in his cert green office, a typewriter on his right, exuding a wonderful, casual confidence that made it look all right.

GALE LOPEZ: Do you like being in New York?

TOM BROKAW: Very much. I’ve always liked it.

LOPEZ: More so than Washington?

BROKAW: No, I don’t think that you can compare the two, the lifestyles are so much different. I like Washington a great deal. I enjoyed living there. But then I’ve enjoyed living almost everywhere I’ve ever been. I just find that it’s a different menu wherever you go.

LOPEZ: But Washington appears to me to be such a provincial kind of town.

BROKAW: That’s a New Yorker’s attitude. One of my attachments to Washington is that I’m a political junkie. I can get a fix there every day and the people that do what I’m most interested in, that is my peers in political reporting, are all there. We can swap tales and compare notes and constantly be assessing and reassessing the political scene. But as for its provincialism, I don’t think that’s any longer true. There’s an enormous influence now in Georgetown, for instance, of younger people, and a lot of interesting places to go. The foreign community is a little stuffy because it’s primarily diplomatic. But I haven’t known it to be provincial.

LOPEZ: Didn’t you start when you were 15 in radio?

BROKAW: Boy disc jockey.

LOPEZ: I wanted to ask you something being at the conventions. I read something in which Richard Wald, the president of NBC News, had said that he thought that the time had come after Vietnam and Watergate for a tougher, more sophisticated kind of show which would appeal to a better informed public. And then he went on to say that you could give the public that sense of getting inside the big story. And I’m quoting here, “The sort of stuff which reporters tell each other over drinks at the bar, but which rarely gets on the air.” Now, can you tell me anything, from either one of the conventions, which didn’t get on the air but which might be kind of juicy?

BROKAW: I think that one of the things that I was really disappointed that we were unable to get on the air is that there was a wonderful character at the Democratic Convention from Boston by the name of Dapper O’Neil.

LOPEZ: Dapper O’Neil?

BROKAW: Dapper O’Neil. An obscure figure who was a right-winger on the Boston City Council. Came here as a Wallace delegate and was determined to get before the audience in some fashion. And he decided that he would use as his vehicle a young man that they nominated as Vice President. And the ‘Dap,’ as he is known to his friends and colleagues in Boston, became suddenly outraged when he found the young man had also lined up to speak for him a practically certifiable nut. A guy who went back to the whole Rockefeller-Zionist conspiracy. I mean the Dap is right out there in the right field, but he didn’t want to be associated with some guy who was off the end of the wall, so to speak. So there was this bizarre caucus going on for about two hours over in the corner between the Dap and these various people, and I was really sad that we couldn’t get it on the air. The Dap is a white-faced Irishman with a roast beef face and a pale green coat and silk shirt and so on, and he had some pal there with kind of Ophthalmologist or 3-D sunglasses that were the biggest coke bottles of glasses I’ve ever seen. The Democratic Convention I think by and large was just pretty dull. At the Republican convention what did not get on air—I think that we probably didn’t adequately convey the strength of passion among those right-wingers who were on the floor—the Conservatives

LOPEZ: The Reaganites.

BROKAW: Yeah. They were really Conservative. The Texas delegation especially. I haven’t had a chance to check this out, but I’m told at the Democratic Convention there were two members of the New Jersey delegation who were determined not to vote for Jimmy Carter. And the Chairman of the delegation was so eager to put up a unified front out of New Jersey, because he thought it would be important for him should Carter win eventually, that he just simply, in true New Jersey fashion, had those delegates removed from the floor.

LOPEZ: I’ve got to talk to you about B.W. Do you know who I’m referring to?

BROKAW: [nods]

LOPEZ: Do you think that the amount of money that she’s being paid in her new position at ABC is a valid salary for a newscaster?

BROKAW: I think it’s very much a matter between Barbara Walters and ABC. I honestly do. If ABC is willing to pay her that and she feels she is worth that much on the market so to speak, then I think she should get it. You know, it’s part of what Republicans and Chamber of Commerce presidents all over this land tell me is the spirit of free enterprise.

LOPEZ: Do you think it’s going to have an effect on the salaries of the rest of you?

BROKAW: I hope so.

LOPEZ: Your eyes are looking ahead.

BROKAW: Well, these are not charitable organizations. If we get large salaries we’re not taking it right out of the hands of widows and orphans. The National Broadcasting Company is in the business of turning a profit. It is not going to sacrifice that profit to pay its various news correspondents, and so on. So if they pay us it will be on the basis of what they can justify economically.

LOPEZ: You were with President Ford in Japan and China, right?

BROKAW: Yes.

LOPEZ: What was it about the Chinese that impressed you the most?

BROKAW: The kind of community cultural discipline of the Chinese. The ability of the society to move almost as one. And the almost religious fervor with which they are devoted to Chairman Mao. I came away really deeply struck by the devotion to Chairman Mao. I may not have been able to read it accurately, but I really believe it’s more than just a political movement or a revolution, that there is the basis of a religion there of sorts. Whether that can be sustained, we’ll see.

LOPEZ: Are you going to be doing any of the feature interviews that Barbara Walters became so renowned for?

BROKAW: You mean the big interviews.

LOPEZ: The big interviews, like maybe with Amy Carter, or—

BROKAW: Well, not Amy Carter.

LOPEZ: Or the Shah of Iran?

BROKAW: I thought we had a rather good beginning when we had Jimmy Carter on. Sure we’ll want to interview the newsmakers.

LOPEZ: In early ’73, the shows ratings hit a peak of 5.9 and then dropped to a near all-time low of 2.7 in July of this year. How do you see your role as host improving that and what specific changes will there be in the show’s format to boost the ratings?

BROKAW: Ratings to me are a little like the Chinese Government. I don’t fully understand what makes a rating go. I don’t know what makes the American television audience respond to one person and not t another. There very seldom are great differences between many television personalities.

LOPEZ: You were also the NBC White House correspondent during Watergate.

BROKAW: Right.

LOPEZ: What do you think is the overall effect that Watergate has had on American journalism?

BROKAW: I think first of all, for a time at least, it made society more fully appreciative of the role of the press. That was important because it was coming right off the Agnew attacks on the press and on the electronic media in the country. And there was disenchantment with what we were doing and there was a suspicion about what our motives were. I think Watergate helped repair that, and for that I am grateful. I see now some backsliding in the public’s attitude toward the press. People do not like to have their favorite myths of idols challenged and as a rule I think that the public does not like bad news. And much of what they hear on our programs they interpret as bad news because it’s change. And that’s what news is, and we’re all creatures of habit, we’re not very happy with it. As far as reporters are concerned, I think it may have been a sharp reminder of the need for a kind of constant vigilance. And that there is nothing like long hours and shoe leather for getting a good story, that you cannot do it in what came to be too quickly the conventional practices. Woodward and Bernstein tracked that story down like a couple of detectives, and were tireless about it. Washington tends to be full of too many traps. I think reporters there do a lot of attending news briefings and news conferences expecting to get the real news out of those relatively sterile environments. But you’ve got to deal with the obscure people as well as the names.

LOPEZ: I’ve heard a lot of people, especially Europeans, who say that Watergate was a whole ploy on the part of Katharine Graham.

BROKAW: Nonsense.

GALE: And that she is really the main power now and how can a newspaper govern America. What do you think of this, is it as absurd as it appears to be to me?

BROKAW: I think it enhances the reputation of The Washington Pot considerably. But you’re only as good as your last story in journalism, even when you’re as powerful as Katharine Graham.

LOPEZ: But did she, in effect, put out Nixon?

BROKAW: She stuck with the story, that’s right. But it was not Katharine Graham who convinced those members of the Judiciary Committee that they should vote impeachment. Nor was it Katharine Graham who told Richard Nixon what to say into those tape recording devices. That’s what undid the president. It wasn’t any kind of trick. He undid himself and the Congress put finally the sufficient pressure on him to drive him out of office.

LOPEZ: Is there such a thing as a scoop in reporting on television?

BROKAW: Sure. I don’t think it’s so much a scoop anymore, we call it a break on a story because it’s all turned over so quickly. If I go on the air at 6:30, the wires pick it up by 7:15, and it’s all over the country in various other publications, and on various other electronic outlets. But you can own a story.

LOPEZ: Have you ever owned one?

BROKAW: One of the early breaks that I had on a story was that they were continuing their practice of organizing reaction to the President’s speeches.

LOPEZ: With Ford they were doing that?

BROKAW: No, no, with Nixon. They were sending out telegrams and I had copies of the memoranda. They were sending out telegrams and phone calls from the White House to organizations like the National Chamber of Commerce and the Handicapped Veterans of War or something like that, in which they were just giving them instructions about the President’s going to speak tomorrow night, we’re expecting so many telegrams form you saying you thought it was a wonderful speech, please try to have them here and that kind of thing, this whole orchestration from the White House. And I had that story pretty well in hand for a while.

LOPEZ: Do you have any of your own theories on the Legionnaires’ disease?

BROKAW: No, I don’t know. I mean, it’s a peculiar virus. I think it demonstrates to us once again how little we know about the world in which we live.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN INTERVIEW’S OCTOBER 1976 ISSUE.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.