New Again: Rob Lowe

Comedy Central’s “Roast of Rob Lowe,” which aired on Labor Day, has been a subject of chatter since last week—primarily due to Ann Coulter’s confusing presence. While the conservative commentator was the subject of a brutal, arguably appropriate comic bashing, there were plenty of jokes leveled at Lowe. A repeat topic of the evening was his 1988 sex tape scandal, and as this advertisement evidences, Lowe wasn’t afraid of poking fun at his past. We’ve come to know him as an adaptable actor, one who’s particularly practiced when it comes to the tricky territory of comedy within drama, and vice versa.

And so today, we look back at Lowe’s feature in the March 1990 issue of Interview. The extensive Q&A was conducted only two years following the scandal, which he speaks about candidly, in addition to addressing his relationships with celebrity, beauty, privacy, and women.

Rob Lowe

By Mike Sager

Rob Lowe’s remarkable good looks—chiseled jaw, piercing blue eyes—have helped him become a movie heartthrob in the tradition of Cary Grant and Robert Redford.

As a young boy in Dayton, Ohio, Lowe saw the stage musical Oliver! And decided he wanted to be an actor. At eight he was playing child roles on local TV, on radio, and onstage in summer stock and college theater. When he was twelve, his mother married her third husband, a Malibu psychiatrist. In Malibu, Lowe redoubled his efforts, taking the two-hour bus trip into Hollywood after school several times a week, auditioning, interviewing with agents, and hoping to get discovered. His friends included the brothers Emilio Estevez and Charlie Sheen, with whom he made home movies.

Following his TV appearances in two ABC Afterschool Specials and in the short-lived series A New Kind of Family, Lowe got his big break in Francis Ford Coppola’s feature film The Outsiders (he skipped his high-school graduation because it conflicted with the shooting schedule). He then played major parts in the movies Class, Oxford Blues, The Hotel New Hampshire, St. Elmo’s Fire, About Last Night, and Masquerade. In 1987 he received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actor with his portrayal of a mentally retarded man in Square Dance. In a cast that included veterans Jason Robards and Jane Alexander, Lowe’s was “the most arresting performance” according to New York Times critic Vincent Canby.

Now twenty-five, Lowe has appeared on-screen with such beauties as Nastassja Kinski, Demi Moore, Jacqueline Bisset, and Amanda Pays. And although he claims to be shy with women, he is said to have been romantically involved with Princess Stephanie of Monaco, actress Melissa Gilbert, and former National Security Council secretary Fawn Hill.

Last spring, a civil suit against Lowe was filed in Fulton County, Georgia, alleging that, while attending the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta in July 1988, Lowe “used his celebrity status as an inducement to females to engage in sexual intercourse, sodomy, and multiple-party sexual activity for his immediate sexual gratification, and for the purpose of making pornographic films of these activities.” The suit was brought by the mother of Jan Parsons, who was sixteen on the night that she and her girlfriend Tara Seburt, twenty-two, met Lowe at a nightspot called Club Rio.

Soon after, the Fulton County District attorney was investigating the criminal allegations. If charged with sexually exploiting a minor to produce pornography, Lowe could have faced a maximum of twenty years in prison and a $100,000 fine. Though charges were never brought, a storm of lurid publicity arose from the lawsuit and from Lowe’s video home movie, the relevant segment of which, seven minutes long, shows the two girls having sex together. Now, on the eve of the release of his new movie, Bad Influence, in which he co-stars with James Spader, Lowe talks about beauty, mistakes, lessons, and the devil in us all.

MIKE SAGER: Aside from a short interview on the Today show, you haven’t talked about the incident in Atlanta. Let’s start from the beginning. You’d been out campaigning for how long before the convention?

ROB LOWE: I started campaigning after the convention. I wanted to wait to see who the nominee was. I didn’t want to blow my effectiveness working for somebody who wasn’t going to win the nomination. And also, frankly, I had been doing two films up to that point and was kind of behind on the candidates. I really used that time in Atlanta to learn more about Governor Dukakis.

SAGER: What was the mood in Atlanta.

LOWE: Conventions are, by nature, a party. I mean, that’s why people become delegates. They come from all over the world to exercise their democratic rights and to party. But the group I was with wasn’t there to party; we were there to observe. There were lots of functions to go to.

SAGER: Who were you hanging out with?

LOWE: Tom Hayden, Ally Sheedy, Alec Baldwin, Ed Asner, Ed Begley Jr., Judd Nelson—that community in Hollywood that’s pretty connected with the social issues. It’s pretty much always the same people.

SAGER: How did it feel to be at the convention? Did you feel you were part of the American political process in motion?

LOWE: At that point I felt purely like an observer. I didn’t feel like part of the process, or that I had any purpose there other than just to absorb. Later, when I was on the road campaigning, I felt more representative of the Democratic Party. In Atlanta I was a private citizen. I wasn’t there representing the party or Dukakis.

SAGER: So on July 16 you flew in from Paris.

LOWE: Right. I was very jet-lagged, I was real tired, and I’d had a couple of drinks, more than a couple. It was in the opening days of the convention.

SAGER: On Sunday evening, July 17th you went to a party given by Ted Turner; then you went to Club Rio.

LOWE: I remember going to the club and being surprised because I was carded at the door. I think most people know I’m over twenty-one, but I was carded at the door. So when it came out that the girl I met there was sixteen, I was shocked.

SAGER: You went in. They put your party in a private room, just off the dance floor.

LOWE: It was private, but instead of a door it had one of those velvet ropes.

SAGER: Were you conscious of being in Atlanta—a place that doesn’t get a lot of celebrities—and being in the public eye?

LOWE: The thing is, I like to go out as if I were an accountant, a doctor, a gas-station guy. I don’t like to let my celebrity interfere with me living my life. I like to meet people, I like to talk to people. I enjoy experiencing life. Being a celebrity can really stand in the way of that. I try not to let it, but that night in particular was a crazy night; people were really, you know, doing their thing.

SAGER: Which is what?

LOWE: They’re buying you drinks, they’re talking to you, they’re not letting you have a lot of privacy.

SAGER: What do they want to talk to you about, usually?

LOWE: Mostly people are interested in how somebody becomes an actor. And then, if they’ve had a couple of drinks, they want to know what Demi Moore’s like or whatever. I mean, I don’t mind people asking that at all, but when you’ve answered it five times… I meet so many people. I want to be genuine and open with everyone, because when I was young and just starting out, I remember I was around people who were successful, and I thought that some were kind of cool or off-putting to their fans. It always really bothered me. So I think I may sometimes go too far out of my way. What happened in Atlanta is a good example

SAGER: How about Jan and Tara? Do you remember how you met them that night?

LOWE: I met a lot of girls, but I very specifically remember meeting Jan, because she was very pretty and she seemed very nice, and she kept walking back and forth past the room. You know, by the seventh pass you notice somebody.

SAGER: Do you remember what she was wearing?

LOWE: No, not really. I was introduced to both girls, and they both seemed interesting or whatever, as people I wanted to know.

SAGER: So you partied, you left the club, you went to the hotel. Now, let’s fast-forward a bit. The thing people really want to know is: Why did he make a videotape?

LOWE: It was just one of those quirky, sort of naughty, sort of wild, sort of, you know, drunken things that people will do from time to time. It’s just one of those things.

SAGER: Was making videotapes of private sex something ongoing at the time in Hollywood? Is it something that people were doing? A fad?

LOWE: I had people come up to me on the street afterward and say, “Hey, you know, I do it all the time. The difference is you got caught.” So without a question, people do it. You think people didn’t Polaroid each other fifteen years ago, when that was the new technology? People should be allowed to do whatever they want in the privacy of their own home or their own hotel room. When people consent to do something, they should be able to do whatever they want.

SAGER: But one of the real problems—the reason for the legal troubles—is that one person was underage. You had no idea at the time that she was sixteen?

LOWE: Absolutely not. How would I?

SAGER: The other real problem was the tape. Were you awake when they left with the tape? What did you think when you found the tape was gone? Or did you give them the tape?

LOWE: You know, we’re starting to go into that area that the lawyers told me not to talk about, purely because there’s the civil suit still in court. Because the legal process is incredibly slow, there are certain things that I just can’t talk about.

SAGER: What was your reaction when you were notified that the mother of the sixteen-year-old was suing you?

LOWE: I felt like I’d been taken. I felt like something I thought was private was now threatening to become public unless I paid an exorbitant amount of money to somebody, and that made me angry. And when I’m angry I’m an incredibly tough person, because I don’t get angry easily.

SAGER: Did you ever believe that something like this could happen? And do you find yourself a bit more guarded these days? What did you feel?

LOWE: I felt betrayed. Half of the anger was at myself, for putting myself in a position where I could get taken advantage of. Then there was, not anger, actually more of a hurt, that people’s motives aren’t always what they seem.

It would have been very easy at that point to really close off. To look at every person I ever met in the street, or in a store, or whoever sent me a drink, or wanted to talk to me or shake my hand—it would have been very easy to close off to them and to look at everybody real suspiciously and go, “Oh, they just want X or Y.” But I made a conscious effort not to let that happen to me.

I can’t help but be a little more gun-shy and wary about people. Contrary to popular belief, I don’t go out very much. When I do go out, a lot of times it’ll be to something like a heavyweight fight, and I’ll be photographed, so that people have this conception that I go out a lot. The fact is, I have a great home and I like to have people come up. I meet enough people just doing my grocery shopping; I don’t need to go out and meet any more people. My life is really based around my house and my friends and my family at the moment, and has been for a while now. There was a period in my life where I went out a lot and I had a really good time. But that period is over.

SAGER: Maybe the incident in Atlanta helped put it to an end?

LOWE: It was ending anyway, but that certainly slammed the door on it.

SAGER: When the news first hit, what was the reaction you experienced?

LOWE: I don’t want to go into names, but I felt like I had been able to attend my own funeral and listen to all the nice things people had to say about me.

SAGER: And were there nice things mostly?

LOWE: I sent out 250 handwritten thank-yous to people who called me or wrote me or whatever—a lot of them people I didn’t even think I knew that well. I have yet to get a negative reaction from anybody in public. Which is not to say the minute I walk past them they’re not giving me the finger. That could be.

SAGER: Was the reaction from other Hollywood men “Welcome to the club, kid”?

LOWE: Exactly.

SAGER: How does it feel to be in that position.

LOWE: Well, I think that in today’s world the right to privacy and freedom of the press are set on a collision course. Whether you’re a presidential front-runner, or an Academy Award-winning actor, or head of a TV ministry, if you stay in the public eye long enough they’re going to try and find a scandal. Anyone who’s lived their life to the fullest extent has a scandal buried somewhere. And anybody who doesn’t have a scandal I have no interest in meeting because they haven’t lived their lives. I mean, you show me someone who’s led a perfect life and I’ll show you a dullard.

It’s sad if you think about it. What kind of person would run for president of the United States in today’s political climate? It would have to be somebody who’s never really been drunk in public, who’s never had an affair, who never shoplifted when they were a little boy, who never had any sort of counseling at all. I just don’t know how you go through your life meeting people, experiencing everything you can, trying to absorb, and not make some of those mistakes. It’s impossible. Plus, you wouldn’t want somebody in office who hasn’t experienced life. People forget, I was twenty-four years old when this thing happened. It would be a little different if I was thirty-four years old, you know what I mean?

SAGER: When this whole thing hit the press, did you close yourself up somewhere?

LOWE: In my house. There were four television crews in my street twenty-four hours a day. They wouldn’t step in my driveway, because I would have them arrested. I couldn’t leave the house, because if they photographed me, then that would have given them an excuse to put something on the news, even if I was just driving my car. They’d ring my buzzer and wake me up at six in the morning and say, “Rob, can we have an interview?” So my friends would come up and bring food and movies. And the press would film each person coming and going.

SAGER: The media furnace must be fed.

LOWE: Then, about four months later, it changed. When you first read about it, it was like I’d been tried and found guilty. But I was never charged with anything; I don’t know if people know that, but I never was. So when the investigation was dropped, people got the idea: “Oh, well, maybe we overreacted a little bit.” Then I got what I call “the sympathetic media.” All of a sudden the crews are back in my driveway. The phone rings and this woman says, “Rob, this is Sandy So-and-so from A Current Affair. We’d just like to tell you that all of our viewers still love you, and we want to know how you’re dealing with everything and your new movie is going.” All of a sudden, she’s the friendliest person in the world. Three months ago they would have lynched me if I’d walked out; now I look through the surveillance monitor and I see this camera crew outside, and they’ve got boxes of lox, cream cheese, donuts, coffee. They’re gesticulating at the boxes and then at their stomachs, like: “Let’s come in and sit around and have brunch and talk.”

It was so absurd I had to think, Is this my life? Is this really what’s happened to me? They even hired a Rob Lowe lookalike to run around outside my house. And they filmed that and then put it on the show, which is supposedly news. What do they call it?

SAGER: Tabloid journalism. Infotainment.

LOWE: That’s it. The scary thing is, you can laugh about it, but it’s scary. Kids are growing up and they don’t know the difference between fact and fiction. The line is getting blurry. I can handle it, you know; I’m a big boy. And the entertainment industry has always been crazy. But the problem is, it spills over into some very serious issues, in politics and real newsworthy stuff.

SAGER: A lot of people think that your involvement in the incident didn’t hurt your career. They say it kind of gave you teeth as an actor and as a public persona.

LOWE: Well, as far as the way people perceive me in my career, I don’t know, because I really make a point of never worrying, or trying not to worry, about the way I’m perceived. You’ll go crazy otherwise. But I will tell you that I’d been committed to do Bad Influence for about four months before the Atlanta story broke. And when it broke, I was about two weeks away from rehearsals. What I had to go through definitely made the performance. It would have been a much different performance had this not happened.

SAGER: Let’s talk about the film. Bad Influence. Produced by Steve Tisch, directed by Curtis Hanson, due at local theaters in March. Can you tell us what it’s about, who do you play, all that?

LOWE: I hate this question—how to make your film sound terrible in one sentence. Bad Influence is about what happens when a person doesn’t face the fact that there is good and evil in each of us, and that you can easily be led to the dark side.

SAGER: What’s your part?

LOWE: My character’s name is Alex, and he’s the bad influence. He forces James Spader, who plays Michael, this upscale yuppie, to reexamine his life. He shows Michael that there is more to life than work, work, work, and having the right car, and the right date, and the right things, the right stuff.

SAGER: And so Alex shows Michael the dark side of the world?

LOWE: Alex introduces Michael to the dark side of himself. Alex is a seducer. He’s a manipulator—

SAGER: A champion of the human urge.

LOWE: Absolutely. Alex basically has no morals. He does whatever suits the occasion and follows his whims, and the only thing that really upsets Alex is people who pretend to be something they’re not, people who are hypocrites. The only thing that you can say about Alex: he is an evil character, he has no morals, but he is honest to himself.

SAGER: So you took the role, and several months later the Atlanta stuff came to light. Did you ever think seriously that you would lose the part or that your career would be over as a result of this thing?

LOWE: My only concern was that I didn’t want to be distracted from doing the work necessary to create this character. This was my first movie in two years. I was really ready to go. And it was fortunate that I was working when this whole thing blew up. It’s part of your job as an actor to put your personal problems behind you and work. Good actors can do that.

SAGER: How did Rob and his Atlanta troubles translate into Alex and his bad influence?

LOWE: I just funneled any stress or any anger or any hurt that I was feeling—I just funneled it into the performance. And, you know, I don’t think I would have been able to give the performance that I gave without this happening to me.

SAGER: Did you have a new roguish feeling to draw on? For a while you were, as they say in the newspapers, an alleged perpetrator.

LOWE: One result that I felt it important to be brazen about what Alex is, and not to back away from it.

SAGER: It seems to me that you have strong feelings about what happened in Atlanta.

LOWE: Yeah, exactly. What people do in their private lives is their business, and shouldn’t be anybody else’s business. And for people to judge people on that… What does the Bible say? Let he who is without sin cast the first stone. Alex has this speech at the end of the movie about being hypocritical. And I guess I put all my frustration and anger and rage into that. Because what this movie says, and what I believe, is that everybody is naughty, everybody is good. Everybody is God. Everybody is the devil. And if you don’t realize you have both parts, that’s what really causes problems.

SAGER: Do you think it’s important to indulge the devil in ourselves?

LOWE: I think you have to. Absolutely. Anything that is stifled will eventually ferment or explode.

SAGER: In other words, everybody needs to party, everybody needs to let loose sometimes.

LOWE: Obviously you don’t want to do it in the way Alex does in Bad Influence, or even in the way that I have in the past. But there are times and places for everything. It’s human nature.

SAGER: You talk about right to privacy and that kind of thing. How responsible do you think you are, as an actor, to be a role model?

LOWE: It doesn’t make you any less of a potential role model to say, “Look, I’ve made these mistakes, and I still make mistakes from time to time.” I don’t think you have to be perfect to be a role model. In fact, as I’ve said, you show me a perfect person and I’ll show you somebody who has lived a very closed life.

I’ll be a role model on my terms, but don’t make a role model on your terms. I think of myself as a human being first and foremost, and secondly as a person whose profession is acting. If people want to make that into something more or less, that’s up to them. As far as my work for causes or social issues, that’s something I’m doing as a private citizen. And yeah, I happen to be a movie star, but I’m not saying, “Hey, I’m a role model. Imitate me.”

SAGER: Along the lines of the right to privacy, yesterday we were sitting here talking and there was some guy ring your doorbell, three or four different times.

LOWE: Right.

SAGER: And he ended up huddling outside your door for most of the evening, waiting for you to talk about—what, he wanted money for college? How often does stuff like that happen?

LOWE: I’m sure the guy was perfectly nice and everything else, but it makes me a little nervous that somebody would hike five miles up my canyon and camp outside my door in a T-shirt in the freezing cold for hours and then act kind of strange. You’ve got to be careful about that kind of thing. That’s just being smart. It seems that people’s reactions to me are usually very charged. So I have to watch it.

SAGER: In a Rolling Stone article that I wrote about the Atlanta incident, there is a quote form a woman who’s part of the same club scene as Jan and Tara. The quote runs: “It’s stupid, because America makes such gods out of its matinee idols. Years ago it was Rudolph Valentino, now it’s Rob Lowe. Hollywood puts him up in a sexual position. They market him so that little girls will go to the movies, buy his posters, fantasize about fucking Rob Lowe. So why wouldn’t Jan want to fuck him if she got the chance?”

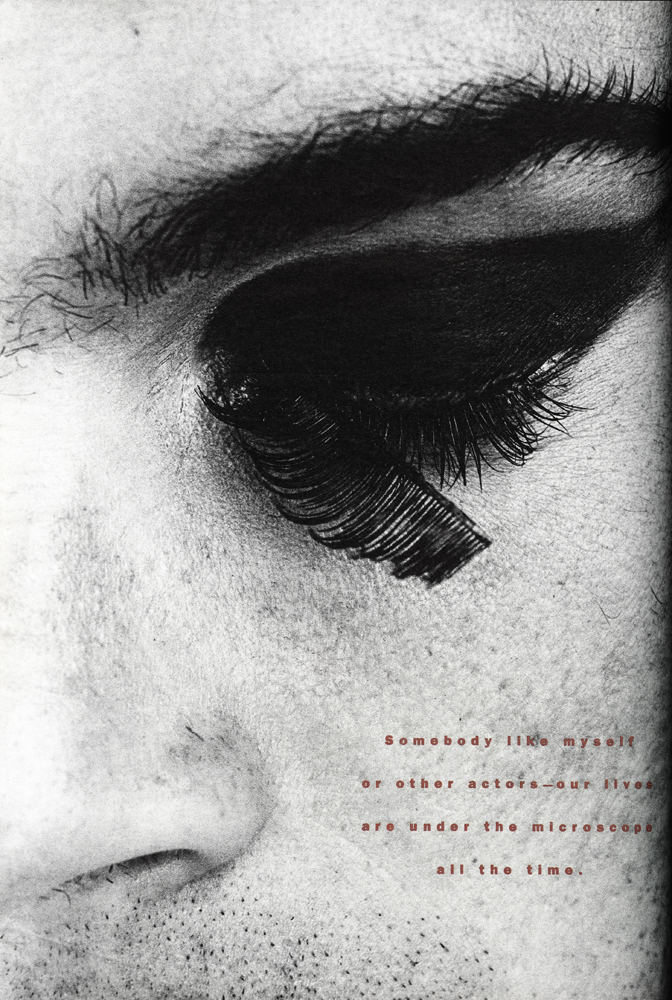

LOWE: Somebody like myself or other actors—our lives are under the microscope all the time. If people are watching me 365 days a year, 360 days they might be bored to tears. And on the other five days, maybe I would qualify as Satan. I mean, take the person reading this article. I’m sure you could pick five days out of the year where they, you know, have done things that they wouldn’t want repeated. The thing is they’re watching me all the time. And they’re not watching everybody else all the time.

SAGER: Supposedly, the crowd that Jan and Tara were part of was into drugs, club crawling, experimenting with lesbianism, threesomes, whatever. I got the impression that those kids were trying to be like Hollywood stars, or at least how they perceive that stars act in Hollywood.

LOWE: And that’s the funny thing: the media have such a strong hand in deciding what people’s perceptions are. They decide what the agenda is going to be, what the issues are. It’s the media that take an isolated incident and make it a deciding factor in a presidential campaign, as opposed to the real issues, like abortion, the homeless, the deficit. The same is true with actors and their lifestyles. The press concentrates on a divorce an actor’s going through and they ignore the good performances he gives, or the causes that he works for. You can’t believe everything you read. It’s never been more true. People have a responsibility, especially with today’s media, to read between the lines. And I’m not talking about reading between he lines of Entertainment Tonight; I’m talking about things that matter, like when you’re reading about an election or the invasion of Panama. Read between the lines, folks, ’cause I’m here to tell you you’re not getting the straight story. Ever. You’re getting variations of the truth, if you’re lucky.

SAGER: Did going through all of this change you?

LOWE: It was a rough year, twenty-five. For the first time you start to sense your own mortality. My grandmother died. We were close. Twenty-five was a milestone. It’s not like I’m worried about gray hairs or losing it on the ball field. But you do get a sense that time goes on.

SAGER: You start feeling like you’re supposed to be carving out a niche for yourself, or—

LOWE: Your interests change. I used to feel that if I spent evenings reading, or watching a film, or just doing nothing up here at the house, I would probably be missing something that was a lot more fun. I don’t have that sense anymore.

SAGER: What do you do around here? Do you hang out by yourself, do you have somebody in, do you usually have a date?

LOWE: I don’t date.

SAGER: I mean an inside date, a hanging date.

LOWE: I don’t bring just anybody here. If I want to get up a basketball game here on my court, for instance, I invite my friends, my buddies I grew up with and went to high school with. The same is true with female dates. This house is like my sanctuary; this is not my public persona.

SAGER: What kind of woman makes it up here? What attracts you?

LOWE: This sounds very California, like some bad Annie Hall parody, but what attracts me is their energy.

SAGER: What kind?

LOWE: They’ve got to have their own agenda, a point of view. It doesn’t even have to be something that I agree with it. I mean, hell, I went out with Fawn Hall. If ever there was somebody that I didn’t disagree with, there’s one.

SAGER: What did you like about her?

LOWE: I was fascinated with the world she came from, and I wanted to know what it was about. She’s a very fascinating, bright woman. We never agreed on anything.

SAGER: Did you discuss politics with her?

LOWE: Oh, yeah. She’s so well versed. Politics: that’s her life. I can talk about how many scene changes there were in Bad Influence and other technical aspects of filming, and she might not necessarily understand, but when she talks about the treaty of 1847 in Nicaragua, I have no idea what she’s talking about.

SAGER: As a regular guy, I’d like to know what it’s like to be incredibly handsome, to have women attracted to you by just your looks. I get the sense that a large percentage of the women who meet you want to go to bed with you. How does that make you feel?

LOWE: In no way would I ever assume when I meet some girl that she wants to sleep with me; that doesn’t enter my mind. I think somebody who did assume that would be such an insufferably arrogant person that you couldn’t be around him.

SAGER: So are you like most people in the sense that you’re sort of pleasantly surprised when somebody says, “I want to go to bed with you”?

LOWE: I don’t know. I never really thought about it, to be honest.

SAGER: Well, not all the questions are supposed to be things you’ve thought about before. So, O.K. Can you talk about yourself in the third person? Can you tell me what is handsome about Rob? What draws people to Rob?

LOWE: If people find me attractive, it would be for reasons that anybody finds anybody attractive. It’s something that comes from within, and it manifests itself physically. You can meet people who are really beautiful. Then, when you see them angry for the first time, all of a sudden they’re not beautiful anymore. They didn’t just step into the other room and have plastic surgery; they’re still the same physically. It’s just that something inside of them has changed. They’re no longer attractive. If people are attracted to me, I like to think it’s because I’m an interesting person, fairly smart, well-rounded, with a good sense of humor. I would like to think that’s what I am. I would like to think people see it.

SAGER: The common wisdom is that handsome people don’t have to rely on the things you just described? How have you managed to overcome your face?

LOWE: Well, I’ve said this a hundred times in interviews. This is me. I didn’t go out and buy my face, right? I mean, if I was starting out and I wanted to be an actor, I wouldn’t have chosen this look, quite honestly.

SAGER: What would you chose?

LOWE: At the moment, the industry’s very into the good-looking, average guy next door who could be, you know, your paperboy.

SAGER: Blue eyes and a broken nose.

LOWE: Yes. Handsome, but not like in the days of Cary Grant or Montgomery Clift or even James Dean. I mean, those were great-looking guys.

SAGER: Do you think you’d be a lot different if you were ugly?

LOWE: You know, people read interviews like this and say, “This guy! Talking about beauty! Jesus Christ!” and they throw the magazine across the room

SAGER: Beauty is part of your life, isn’t it? It’s you. It’s your product.

LOWE: See, it’s interesting to you, but to me it’s totally irrelevant.

SAGER: Still, how does it affect your life to know that in certain arenas you can have whatever you want?

LOWE: I don’t know. The life of a movie actor is certainly unique, and a lot of what you say is true. As much of a mistake as it would be to take that for granted, it would be an equal mistake to deny it. It’s something you have to get used to, something that takes a while to learn to deal with. Atlanta is a perfect example of a time when I didn’t deal with it well.

SAGER: That was one kind of encounter with the way you attract. Tell me about yourself and women.

LOWE: I’ve always found women more interesting than men. In school, I had two or three best guy friends, but mostly if I was just hanging, I’d like to talk to the girls, because they were more interesting. I think they were smarter. I don’t think that women are smarter than men, or that men are smarter than women, but I’ve always enjoyed the company of women.

SAGER: Does being an actor do something to a person?

LOWE: As an actor, you deal in fantasy, imagination, and concentration. Those are your three weapons. Those are your bullets. It’s easy to live in a fantasy world, and that’s why I refuse to live in an isolated environment. I’m not going to stop talking to people who come up to me in an airport. I’m not going to worry about what may be their ulterior motive.

SAGER: A lot of successful men and women are sure that any moment the rest of the world is going to realize they’ve just been faking it all along. Is this true of you?

LOWE: That’s absolutely true. I still keep thinking that it’s all been a cruel joke, that it’s all going to go away. But everybody feels that way. I certainly do, I feel like every movie is definitely the last one that I’ve had my moment; that I’m going to be selling autographs at malls.

SAGER: Last spring and summer you were in the middle of a raging shitstorm. The district attorney was investigating. The allegations were serious. Did you face the possibility that you could go to jail for twenty years or—

LOWE: No, I never did, because I always knew what I happened. I was there. The newspapers, as usual, only knew one side. To me, this was no different from anything else, like I’m marrying Madonna or some other bullshit, you know? I know what happened in Atlanta and I know that, if it came to it, I would tell my side of the story and that would be that.

SAGER: Do you feel you made a mistake?

LOWE: Yes, I made a mistake. I misjudged people. I was careless. I used bad judgment. Those are three big mistakes.

SAGER: Did you—

LOWE: And I take responsibility for those three mistakes. When it happened, people I knew would say, “Rob, you seem to be taking this pretty well.” My attitude was this: I got myself into this mess, so I’m the only person who can get myself out of it. I just had to deal with it.

SAGER: And you dealt with it partly by doing a kind of penance, isn’t that true? After the incident, you and your advisers sat down with the Fulton County district attorney, and it was decided that, even though there’d be no criminal prosecution, a show of good faith on your part would be welcome. So you promised to perform twenty hours or community service. If you were innocent, why did you agree to do this?

LOWE: They had not brought any charges. But I was in the middle of doing this film. The publicity and the accusations were constantly there. They were distracting me from my work. I flew to Atlanta, my father met me there, and we met with the D.A. and worked out a satisfactory way to express my concern over the whole event. We decided I’d do community service once the film was finished. I do community service all the time, anyway.

What was real nice about it was the district attorney allowed me to set it up outside the country, and it was left up to me as to what exactly I wanted to do.

SAGER: Where did you end up going?

LOWE: I went to my hometown, Dayton, Ohio. I went in the men’s correctional and women’s correctional facilities, to a couple of halfway houses, and to detention centers for teenagers and kids.

SAGER: What did you talk about?

LOWE: The basic thing I said is: Just because people will say you have fucked up does not mean you are fucked up. And whether you’re a movie star or doing time in a correctional institute, everybody can have bad judgment, and it’s something you have to address. You learn to go on from it. It shouldn’t stand in your way. You shouldn’t let people continue to throw it in your face. Everybody makes mistakes. It’s the same point that Bad Influence makes. People are human. There’s such a premium today on being perfect. That’s just not the way people are.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.