New Again: Patti Smith

Earlier this week, iconic musician, visual artist, and New York Times best-selling author Patti Smith released her second memoir, M Train. The first, Just Kids (2010), won a National Book Award for nonfiction and fulfilled a 20-year-old promise to ex-lover and best friend, the late photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. While Just Kids conveys the emotional highs and deep, deep lows of Smith’s relationship with Mapplethorpe (until his death in 1989 from complications with AIDS), M Train brings readers on a journey to different “stations”—a metaphor to represent various locations that the artist considers pivotal points in her personal and creative life. Not only is Smith releasing M Train this month, but this year also marks the 40th anniversary of her seminal album Horses and it has been announced that Just Kids will be turned into a mini series (in 2011 the rumors were a feature film).

To celebrate the 68-year-old’s ongoing success, here we present an interview with Smith from February 1976, when she was just 29 years-old. As her second time being featured in Interview, the artist was interviewed by the late model, actress, and designer Maxime de la Falaise, who helped to nurture Mapplethorpe’s career, despite an affair he had with her husband at the time, John McKendry—all of which is recounted in Just Kids. —Kira Harada-Stone

Patti Smith

By Maxime de la Falaise McKendry

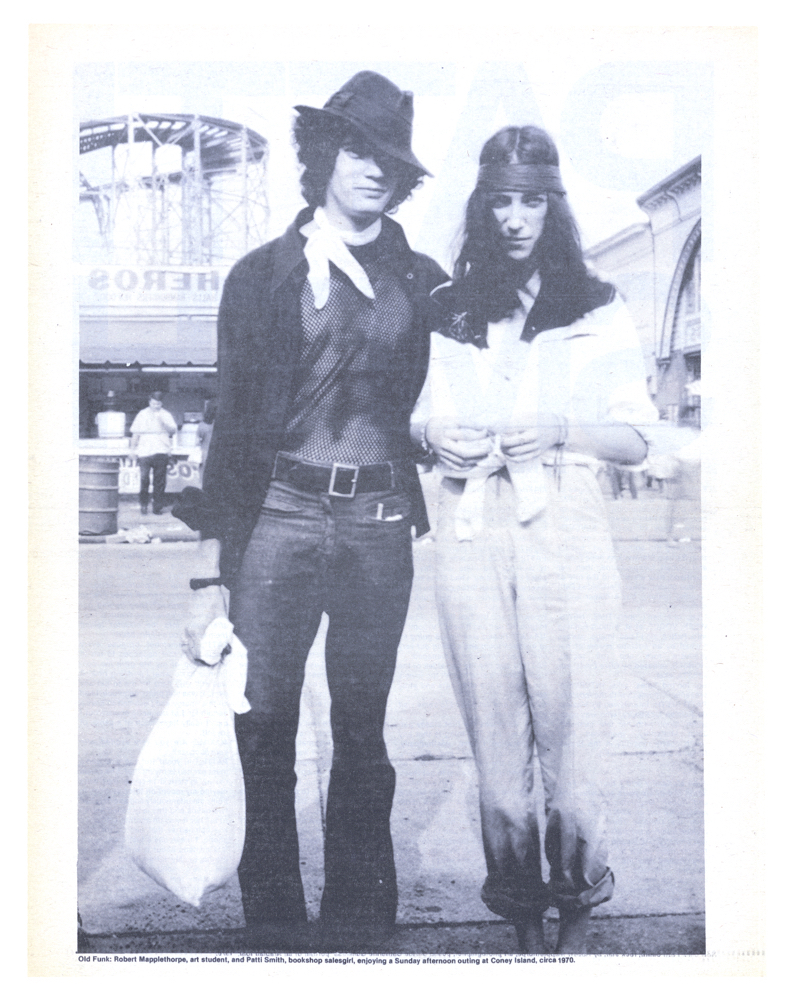

Patti Smith first graced the pages of Interview way-back-when in 1972. Glenn O’Brien ecstatically noted the appearance of Patti’s latest very-limited-edition book of poems Seventh Heaven (“$1 at better stores”), describing the authoress as “badder than Barbara Stanwyck as Belle Starr,” and Robert Mapplethorpe, then her boyfriend, now elevated to the role of official photographer, Polaroided Patti wearing nothing but a diaper and a dishtowel. Now, one can’t open Times, Newsweek, Vogue, et al. without running into Patti’s ain’t-I-bad image, always framed by an ecstatic review of her premiere rock ‘n’ roll record, Horses, released by Clive Davis’s hot Artista label. So, for old times’ sake, Interview presents poetess-with-the-mostest, Patti Smith, interviewed by Maxime de Falaise McKendry, who way-back-when, along with her late husband, John McKendry, sponsored Patti Smith poetry readings in the British Colonial drawing room.

———

John McKendry and I first met Patti Smith five or six years ago when she and Robert Mapplethorpe shared a ramshackle loft on 23rd street not far from Chelsea Hotel. Originally divided into two separate spaces, they had broken a big, jagged hole through the partition, much to the landlord’s fury. Robert had the front area, its amazing neatness seeming almost prim beside the erotic content of his assemblages. Through the gaping hole one stepped into Patti’s quarters: darker than Robert’s, dusty, seemingly full of rags as though nothing really mattered, except the Hermes typewriter and the sheaves of paper on the large, unmade bed.

MAXIME DE LA FALAISE MCKENDRY: Do you remember that funny loft, Patti?

PATTI SMITH: Whenever I pass by I still get a pang. It was the longest home I ever had.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: I always think of you as being in total darkness there.

SMITH: It’s true. One time the electricity was out and there was this long piece I was writing. I had some kind of fever and I had all these candles lit and I was drinking rum and I got drunk and my manuscript caught fire in the typewriter and the first thing I did was grab the rum and it went, “Vroom!”

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Robert was always going into his back room and coming out very chic. I don’t know how he managed.

SMITH: It was like the two sides of the track: Robert’s side had all the jewels and I had all the stray cats and stray boys.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: And John used to come visit you all the time.

SMITH: John was the first classy person I ever met. The thing is that any sophistication I have, aesthetically, comes from Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. In the ’60s I never missed an issue even if I had to steal to get them. I come from a real working class background and I didn’t know anyone sophisticated—except I saw Edie Sedgewick once at the Art Museum in Philly. She had these black leotards and little black pumps and this big ermine cape and all these white dogs and black sunglasses and black eyes. She was classy! That’s what I though about John when I first met him. I could always count on him having silk shirts and a Cartier watch. John really changed us. When we first met him we were completely poverty-stricken. I was selling little drawings here and there and I’d go all day on two jelly donuts and a cup of coffee. I was crazy about John because he always talked about rock ‘n’ roll in the same way he would about Steiglitz or Georgia O’Keefe. I mean, I’m still trying to make people understand that I really equate Mick Jagger and Rimbaud. I’ll do a reading they’ll say, “You’re doing too much rock ‘n’ roll,” and then I’ll sing and they’ll say, “You’re not enough rock ‘n’ roll.” But to me they’re all the same thing. It depends on the rhythm of the moment.

That was one cool thing about John: we could sit and talk about Artaud and Keith Richards in the same breath because anything that was passionate or beautiful seemed to be the same to John. Also, he relaxed me. You probably noticed the way I used to act when we came to your house to dinner. I may have seemed cold or shy but I was really just nervous because I had a really strict upbringing about being with people even just a few years older than myself. We were really taught a dividing line between the kids and the elders. When I first met John I couldn’t relate to anybody. I was about 23 and I’d be flanked between John Richardson and Lily Auchincloss and I couldn’t say anything. I’d just sit there. It’s still hard for me to call Clive Davis, “Clive.” It’s still “Mr. Davis.”

FALAISE MCKENDRY: What about Mick Jagger?

SMITH: He’s not anything yet. I haven’t run into him. The Stones seem like the last ones, the last ones to conquer.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Are you still in love with Rimbaud?

SMITH: Hannibal? Oh, Rimbaud! I love ‘em all, any good-looking guy. But the thing about John was he was a “grown-up” but you know there was no way you could call John grown-up. He relaxed me and then I started to realize that nobody every really grows up. One time he told me stories about when you were in a troupe, a highwire act or something?

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Oh! In Paris when I used to be a clown!

SMITH: That’s right! You used to dress as a ballet dancer and were always having affairs—he had you on a highwire or something?

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Having affairs on a highwire—what a dare devil I must have been! Do you remember when we did one of your first poetry readings in our living room and all those French publishers arrived? They freaked out and left after about five minutes. I ran after them into the elevator telling them about you and Rimbaud!

SMITH: I remember because every single thing that happened to me in that period of my life gave me confidence to do what I’m doing now. It was still very hard for me to get any work. It was still pretty nebulous. I had all this energy and I seemed to have a certain kind of magnetic powers but I didn’t really have much of a sense of myself.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Are you very excited with your success?

SMITH: Oh yeah, but the one who’s most excited is my mother. She called me up hysterical because they were playing my record on three stations in Philly simultaneously and she only had two radios and this lady called her up to tell her it was on another station so she listened to that one on the telephone. I mean she’s just crazy, she’s just ecstatic about it, and that makes me happy. My father hated rock ‘n’ roll. He’s solid, he likes Duke Ellington—real cool, quiet jazz or classical music. He’s a real intellectual. He’s into the elegance of the mind as opposed to the banal sexuality of rock ‘n’ roll. He has real good speech and stuff like that. He’s very Mark Twain-ish. He reads a lot. He knows the Bible by heart. He’s worked at the same factory since I was born, 28, 29 years ago, and when he gets home he spends his time in three blocks. First he gets all these racing forms and tries to beat the system scientifically. Then he works on his UFO studies. And then he goes on to the Bible and traces the scientific fallacies and pornography in the Bible. That was my favorite.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: It gave you a rich soil to grow in.

SMITH: Exactly, because I was real religious when I was young. I wanted to be a missionary. I was a Jehovah’s Witness for a long time and I was always going out to preach. I must have been so pathetic because I was so skinny. I had these Brownie socks. I was real proud of the Brownie logo. I wasn’t even a Brownie. I just got them—hot Brownie socks! And this little brown and white checkered dress with smocking. And I’d had scarlet fever and I’d lost most of my hair. I just had little tufts, and my mother was always trying to hide it by putting these huge plaid ribbons on my head. I’d go out every Saturday and take my Watchtowers and Awakes! because I was real serious about it. I had this idea that the coolest thing that could happen to you was talking with God. My father was always talking about God, and I idolized my father, so I’d spend hours trying to have mental telepathy with God.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: As a stage towards God you could always aim for being President. Rock ‘n’ roll songs would be better than presidential speeches. What would you do if you woke tomorrow morning and by some mischance you were President of the United States?

SMITH: First thing I’d do would be to abolish organized religion. I’d break up the power of the Mormons in Utah. Then I’d get a Cabinet together. I think I’d make Lenny Kaye, my lead guitar, an ambassador to try and patch up relations with Jamaica, and then have some long talks with Bob Marley and see if we couldn’t open up Rastafarianism so that it is not a racial religion because I think it’s a great religion. It has dope and rock ‘n’ roll—what a great religion! I realize that people need something to believe in.

I mean, I always used to seek it from religion and then it just wasn’t satisfying enough, so I moved to art and that really peaked when I met Robert. I was really very psychotic when I met him. I was still very young with totally maniac energy and really self-destructive. I was around 19, and he was a real flower-child with real long curly hair and raggedy clothes and no shoes and so shy he’d never talk to anyone. That was when we really fell in love, about 10 years ago. And I used to cry. He taught me how to put all my madness in a form because I was so emotional, so shaky, and my metabolism was so high. He forced me to pour into work because he really worked night and day. He’d be up all night working on art. And I worked at Scribner’s and then we’d rest and eat and then we’d be up ’til around four doing art. And then I’d get up the next day and go to work. We were really just like a little art factory but it really re-oriented by energy.

We were living in this real hole in Brooklyn for a long time but then it got really dangerous. It was near Pratt Institute and some of our friends got shot and we were looking for a new horizon. I was really interested in finding out what I was going to do in art because my drawings had got to a certain point where I felt I wasn’t really interested. So I started to take photographs. The writer Alain Robbe-Grillet was a great influence on me—I read Snapshots and I liked the way he’d frame things. But anyone would get a headache from looking at my photographs because what I did was just take a corner of something and frame it. But as photographs, they didn’t really make it. I didn’t know what to do. I was writing words on my drawings and Robert loved the little poems on my drawings. He made me recite them to him.

By then I saved some money and I went to Paris because that was the dream—to go to Paris and study art. And that’s when I got disillusioned with art. Carting all these piles of paper, all this crap around, I couldn’t be free. I couldn’t be impulsive which is what the whole beauty of being a traveler is about. With all my art to carry around, it was like having a kid. I started thinking what could happen with my art and I realized that the biggest thing that could is that it winds up in a museum. It’s like finding a rare animal and putting it in the zoo. I started resenting how much art robs from life. I’d go to a party and I couldn’t enjoy myself, even sexually. All I could think was how I was going to reinvent the experience into a piece of art. So I just chucked it. It was terribly painful. I was so used to doing art that my fingers were like albino spiders. So it was just natural for me to go to a typewriter and write poetry.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: And now you write songs. Do you find a difference now between a poem and song, between words that are to be silently and others that are to be sung?

SMITH: Well I used to divide them up. I used to write more noticeably rhythmical poems that were like rock ‘n’ roll songs. I was just starting to use the typewriter and the only way I could relate to it was to think of it as some sort of instrument and I’d put on Stones songs or something I’d try to write my poems in a certain rhythm. I had my rock ‘n’ roll stuff for performing and my denser stuff for writing. But now it’s like what I said when we were talking about John: I don’t separate anything anymore. All the traumas I went through separating art from writing don’t exist anymore. That’s why I love being in rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a whole life thing. You’re not a rock ‘n’ roll person four hours a day or even when you’re on stage. It’s become the rhythm of your whole life. I go to Sutters to buy some coffee and everybody relates to me in a different way.

FALAISE MCKENDRY: Are people coming at you a lot in the street?

SMITH: All over the place. They stop their cars. I like it because mostly they say stuff like, “Good luck” or “Knock ’em dead honey!”—you know, older ladies and stuff like that. It’s never happened to me like this. I went away for three weeks when my record came out and I come back and it’s a whole new… Oh, I was all over the place! I think it’s no accident that I’m in rock ‘n’ roll. First it was religion, and then it was art, but what I’ve always tried to do is to express the highest point of me, and rock ‘n’ roll is the first and the most open form created by our generation. The cool thing about it is that you get the power, you get the rhythm; you can be taken over sexually, you can be taken over cerebrally; it’s great to look at—it’s a package deal.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE FEBRUARY 1976 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.