New Again: Grease

In June 1978, what has become one of the most successful movie musicals of all time hit the big screen: Grease. Nearly 40 years following the film’s release and 45 years since its Broadway debut, the classic has now been reinvented with Grease: Live! Performed as a live musical on television, the production featured the likes of Julianne Hough, Keke Palmer, and Vanessa Hudgens. Though Grease: Live! could have ended disastrously, it drew 12.2 million viewers (more than four times the collective viewership of the Screen Actors Guild Awards, which aired at the same time) and was met with much acclaim.

The live production’s success spurred us to look back to the beginning. Here, we revisit an article from 1986 with Grease‘s original Musical Director Tom Moore and Film Director Randal Kleiser, wherein they talk about the project that would define the rest of their careers. —Sidney Butler

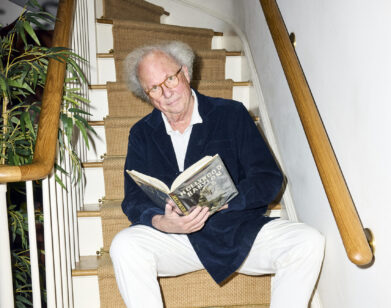

Randal Kleiser

“When I was a boy,” says Randal Kleiser, “Walt Disney was my idol.” At the age of 12, Kleiser spent six months making an animated cartoon and stopped by the gates of Disney Studios to see if he could show Walt his film. “The guard turned me away,” says Kleiser. “I gave up cartoons and started making live-action films.” That some 28 years later Disney Studios produced Kleiser’s Flight of the Navigator—the story of a 12-year-old boy and his spaceship, and the delicate relationship between the boy and his family—is testament not only to Kleiser’s determination but to his talent for making fantasy reality.

Kleiser, probably best known for the film version of the blockbuster Grease and the luscious, if controversial Blue Lagoon and Summer Lovers, has earned the reputation of being a “teenage director” with a perhaps overly romanticized vision of coming of age and teenage sex. It’s a label that Kleiser not only accepts but defends, especially when talking about the other hot directors of the genre, like John Hughes. “I think he has a good beat on the way teenagers really feel. My films are purposefully a little more idealized and bigger than life.”

Kleiser’s own youth may seem a bit idealized; he was reared in the protected environs of upper-class suburbia on Philadelphia’s Main Line, leading what he calls “a very sheltered life.” But his particular sensitivity to the raw emotions and blossoming sexuality of teenagers reflects a fantasy life born of his boyhood summers in Seaside Park, New Jersey. “I remember those as my favorite times—the white hot sand and the water. I’m drawn to places with lush greenery, and to themes of escaping to a placed where there’s too much freedom.” His own high school years are not ones he remembers so idyllically. “I was pretty much rejected in high school. While all the other kids were playing football and joining school activities, I was making 8mm film. It wasn’t until the last week of my senior year, when I showed the school my film, that the kids realized what I had been doing all that time and began to look at me differently.”

Cutting his Hollywood teeth on the popular television series Marcus Welby, M.D. and Family, Kleiser went on to made-for-television movies, directing John Travolta in The Boy in the Plastic Bubble and Ed Asner in The Gathering, the latter earning Kleiser an Emmy nomination for Best Director in 1978. But not until Flight of the Navigator has Kleiser’s big-screen box-office success been matched by critical acclaim.

For the future, “I’d like to try a thriller or murder mystery. I can identify with paranoia pretty easily.” But that’s not to say that Kleiser is turning his back on his faithful younger audience or the beauty and romanticism that are his trademarks. “The two hours the audience gives you should be an uplifting journey. My payoff is when the audience comes out talking, obviously happy and feeling better after a tough day. It sounds phony, but in that respect, I’ve done everything I’ve ever wanted.”

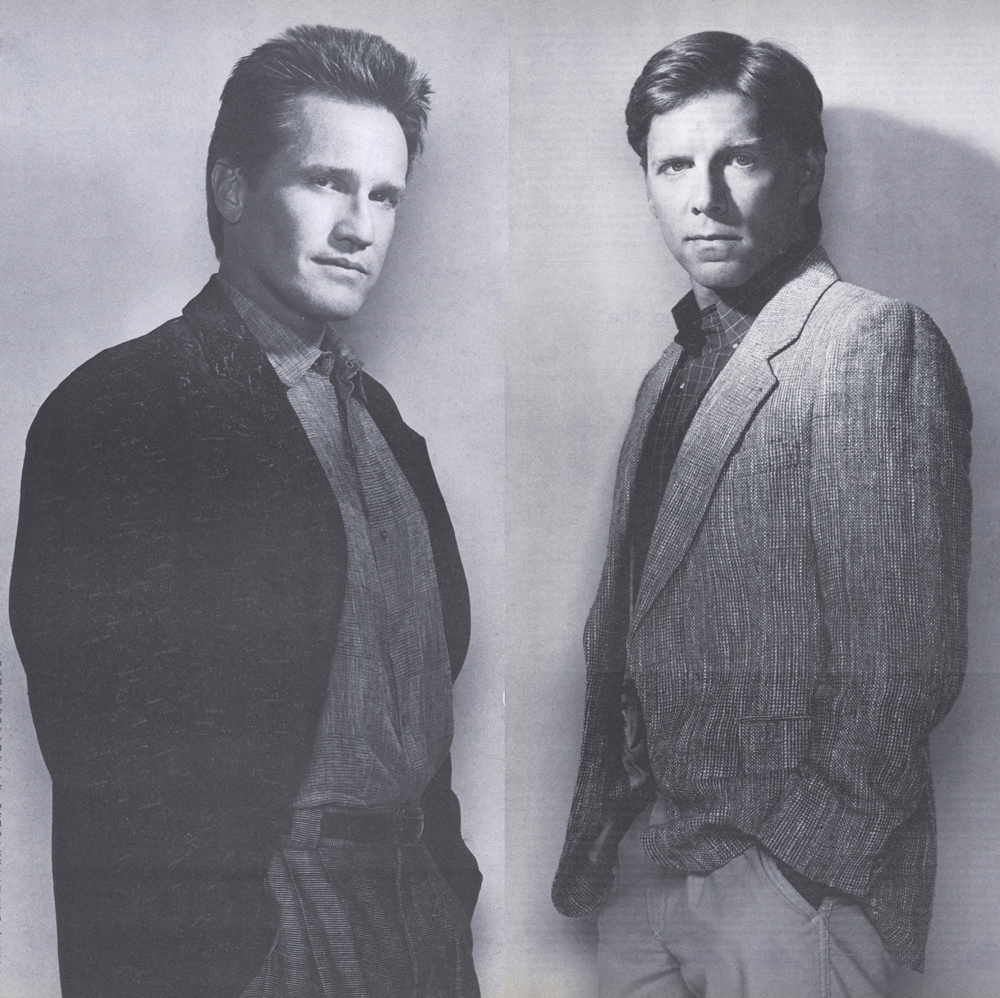

Tom Moore

Before this year Tom Moore was, without question, one of Hollywood’s great untapped resources. Well-known for his work on Broadway and throughout the country, the 39-year-old director had long been a victim of the film industry’s tacit belief that if it doesn’t happen on a screen, it doesn’t exist. Now all that has changed with the completion of Moore’s first feature, the film adaptation of Marsha Norman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama ‘night, Mother (starring Sissy Spacek and Anne Bancroft), which opened to excellent reviews last month.

Moore’s personal story began rather simply. Born in Mississippi and raised in the Midwest, he had directed nothing more than a 10-minute play as a student at Purdue when he was accepted into Yale Drama School’s prestigious Master Director’s Program. “I still don’t know how it happened,” says Moore now. “I’ve had a charmed life and these amazing things keep happening unexpectedly.” The next turning point came immediately after graduation, when producers Ken Waissman and Maxine Fox took a chance on the first time director to help them develop a teen musical for Broadway. Moore drastically reworked the show’s structure and is largely responsible for making Grease the second longest-running musical in Broadway history (recently deposed from the number one spot by A Chorus Line). With points in the property, the director quickly became prosperous and was hailed as the Golden Boy of American theater. Then came the crash. Producer Allan Carr bought the film rights and passed over Moore as director in favor of Randal Kleiser, a decision which Moore—after eight years to reconsider—now recognizes as valid. “The film was, first and foremost Allan Carr’s vision. Still, it’s hard watching all your work being used and not sharing the credit—although I did share financially, which saved my feelings to a great extent.”

From 1972 on, Moore continued to hone his directing skills on Broadway (Over Here, Division Street, The Octet Bridge Club) and around the country at the Old Globe, American Conservatory Theater, Arena Stage and the Guthrie and Mark Taper Forum, now his primary theatrical base in Los Angeles. Still, a film career eluded him. Moore tried television but found the breakneck pace too limiting. So when Marsha Norman (whose play Getting Out won an Obie in 1979) presented Moore with the script for a two-woman drama called ‘night, Mother, he recognized not only a great literary talent (Moore compares her work to Chekhov’s), but also a reflection of his own darkly comic Southern vision. With Ann Pitoniak and Kathy Bates cast as mother and daughter caught in a hilarious, ultimately fatal domestic web, ‘night, Mother dominated Broadway for a year, won the Pulitzer for Norman and fixed another feather in Moore’s theatrical cap.

The play’s path to the big screen was not so easy. “The machinations of getting anything done in Hollywood are just as horrible as anyone ever dreamed,” says the director. “The project clearly needed a star in order to happen.” Even with Spacek’s name attached, however, it took a year and a half of studio turnabouts, executive changes and renegings for ‘night, Mother to find a home with the unexpected production team of Aaron Spelling (as the first feature under his independent banner) and Universal Pictures. In danger again of losing out to a big-name director, Moore was saved by Marsha Norman, who insisted on his being hired. “If this hadn’t happened, I would have missed my chance, period,” says Moore with some relief. With stars and crew agreeing to work for fractions of their normal salaries, ‘night, Mother was shot for an unheard of budget of $3 million, and the result is a two-woman tour de force somewhere between Tennessee Williams and Ingmar Bergman. “People who want to see great acting will come to see this movie,” says Moore of his formidable cast. As for the difficult subject matter ‘night, Mother‘s appeal for Middle America seems questionable. “It’s not depressing, it’s cathartic,” the director says of the final gunshot. His own career, in any case, is finally off with a bang.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE OCTOBER 1986 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs on Wednesdays. For more, click here.