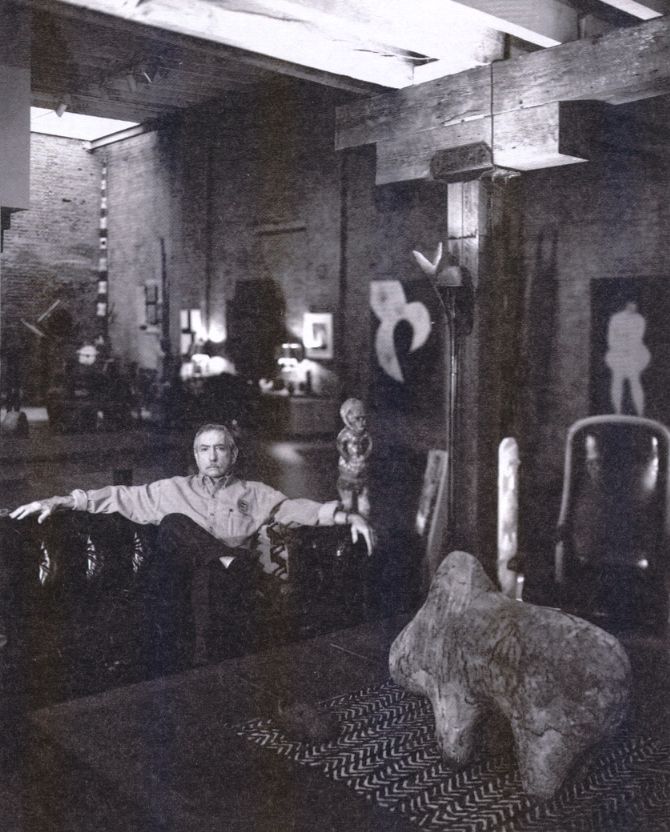

Edward Albee

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

50 years ago last weekend, Edward Albee erected the timelessly tragic characters George and Martha in the Broadway premiere of his world-renowned play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, propelling him toward a career of artfully relaying the human condition on stage. A series of academic expulsions, a premature departure from the home of his adoptive parents, and 32 plays later, Albee has garnered a wealth of recognition, from Pulitzer Prizes to a Tony “Lifetime Achievement” Award, which only chip at his artistic legacy.

On the same day half a lifetime later, an 84-year-old Albee saw Broadway revive the perennially feuding couple once more at the Booth Theatre, with Tracy Letts as George. Here, we revisit Albee’s conversation with Steven Drukman, a young playwright hoping to glean from a thing or two from the seasoned dramatist, which ran in the March 2002 issue of Interview. Albee discusses his plays Occupant (2001) and The Goat or Who is Sylvia? (2002), and counsels Drukman on facing one’s fears and breeding creativity through the unconscious. —Somala Diby

Edward Albee: Who’s Afraid of Controversy? Not This Playwright

by Steven Drukman

Edward Albee is famous for, among other things, writing the most notorious non-winner of the Pulitzer Prize for drama in history: the 1962 play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Pulitzer judge W.D. Maxwell considered the play “filthy,” causing several committee members to resign in protest.) It did no lasting harm to Albee, who eventually went on to win three Pulitzers, anyway—for A Delicate Balance (1967), Seascape (1975) and Three Tall Women (1994)—and who shows no sign of slowing down. His play about sculptor Louise Nevelson, Occupant, has just opened at Off-Broadway’s Signature Theatre (starring Anne Bancroft), and The Goat or Who is Sylvia? opens this month on Broadway, starring Mercedes Ruehl and Bill Pullman.

STEVEN DRUKMAN: The first time we met, I told you I had just finished the first draft of my first play, and you gave me some advice, which I followed.

EDWARD ALBEE: Sorry.

DRUKMAN: It was, “Don’t let your characters be flags in a parade.”

ALBEE: That’s not bad.

DRUKMAN: It’s good advice for a journalist who’s trying to become a playwright, to not impose his voice on the characters. You said, “Let your unconscious seep through.”

ALBEE: Mm hmm. That makes sense.

DRUKMAN: It’s interesting for people to learn about your particular process of writing a play.

ALBEE: It’s very simple. I discover that I am thinking about a play. I am not a person who gets ideas for a play: “Oh wow, wouldn’t it be good to write a play about this.” I write the plays to find out why I’m writing them. I’m aware that I’m “with play” and usually it comes to term. By the time I’ve finished the piece I’ve gotten so involved with the reality of it that I don’t think much about what caused it.

DRUKMAN: I hear characters speaking in my head. Does that happen to you?

ALBEE: Yes. I conduct an experiment to find out how well I know my characters. I will take a walk on the beach and think up some situation that can’t be in the play that I’m planning to write, and for a half hour or so I’ll walk around with my characters, making them improvise dialogue for that situation. And if I can see and hear them exiting three-dimensionally in an improvised situation, that indicates to me I probably know them fairly well, and maybe I can trust them to be in my play.

DRUKMAN: So I would imagine you’d do less rewriting than most playwrights would.

ALBEE: Yes. I wait a long time before I write the play down. I trust my intuition and don’t rewrite very much. Like everybody else I write a little too much and get carried away with the sound of my own voice, but I can cut. And I’ve learned one other important thing: If you have some notion as to where you’re going, and in the middle of the play you find out that it’s changing, trust your intuition.

DRUKMAN: I wonder how that translates to your teaching, because it’s very hard to teach someone to let the unconscious seep out.

ALBEE: I can’t teach anybody to be a playwright. But I can help them think coherently as playwrights, and help push them in the direction of understanding how their creativity should work. That’s all I do. I tell my students, not only should you know everything anybody else has ever written, you should know the bad stuff as well as the good. Because you don’t want to be influenced by the bad stuff. You should also note the history of classical music, since you’re writing stuff that is to be spoken and heard; and since you’re also working with visual images, you should know about painting and sculpture.

DRUKMAN: Tell me about Occupant, your new play about Louise Nevelson.

ALBEE: It is a life story of a girl born in Russia in 1899 named Leah Berliawsky, whose father came to Maine, started a junk store and brought over his family. She realized that she was moved by the arts and started drawing when she was very, very young. Over the years, Leah invented and created and became Louise Nevelson, the sculptor. She made lots of mistakes along the way—a marriage she shouldn’t have made, kids she didn’t want. Then she abandoned all of that and went to Europe, living a hand-to-mouth bohemian existence, going to art schools and being rejected for 35 years or so until finally she became on of the most famous sculptors in America.

DRUKMAN: And she was a friend of yours?

ALBEE: Oh yeah. We knew each other for 25 years or so. I’m interested in how people create themselves. All artists do it. I told a lot of visual artists that I was doing this play and they said, “That fascinates me—how we do that, how we become out art.” I wrote the play in two months.

DRUKMAN: Really?

ALBEE: Yeah. It just sort of flowed beautifully.

DRUKMAN: Now with your other new play, The Goat, I think it was about three years ago when I saw it in your notebook.

ALBEE: I was beginning it then, and I finished it about a year and a half ago. [sigh] What can I tell you about it? It’s one long act, three scenes, four characters and a goat.

DRUKMAN: [laughs] Well, that’s a beginning. You told me it was your most overtly political play.

ALBEE: It’s about the limits of our tolerance; what we will permit ourselves to think about. I saw how we don’t behave properly when Susan Sontag wrote her piece in The New Yorker [after 9/11, in which she tried to play the event in an historical context] and really got castigated. This play relates to that, what we may permit ourselves to think about, and I consider that to be political.

DRUKMAN: So the goat is not a scapegoat.

ALBEE: No. I chose the title The Goat or Who is Sylvia?—the goat is name Sylvia—because I wanted the double goat. There’s a real goat and also a person who becomes a scapegoat. It is a play that seems to be one thing at the beginning, but the chasm opens as we go further into it. And I think it is going to shock and disgust a number of people. With any luck, there will be people standing up, shaking their fists during the performance and throwing things at the stage. I hope so!

DRUKMAN: Oh great. I love plays that cause problems; there are so few of them now. So there’s this question that journalists keep asking you—”What do your plays mean?”

ALBEE: They mean what they say. Any halfway decent work of art has metaphor and resonance and subtext, and no two people receive the same play because no two people bring the same equipment, or willingness to participate, in the play.

DRUKMAN: Do you think you write with the sensibility of someone who was adopted?

ALBEE: Well, being adopted, my allegiances were toward inventing myself, like Nevelson. I didn’t have all sorts of extranea, like family ties. I had to be the first person in my line.

DRUKMAN: But there’s also the idea that no matter how well a person is adjusted to their new family, they are still playing a role.

ALBEE: To treat your own life stuff as subject matter, you mean? Yes, I’ve always liked to think that I can stand off and observe myself in any situation without participating in it.

DRUKMAN: Did you know that disproportionate amounts of adopted people are playwrights?

ALBEE: Really? With you, that’s two of us. [laughs]

DRUKMAN: And Craig Lucas [author of Prelude to a Kiss]. And Richard Foreman [avant-garde director and playwright].

ALBEE: Maybe we’re all from the same parents. [laughs] And we’re probably all bastards, anyway.

DRUKMAN: [laughs] It’s funny how you got this reputation as being a humorless, dour person.

ALBEE: That goes back to the early days when I was far shyer than I am now; when being interviewed, my shyness sort of manifested itself as a kind of surliness. Now I have developed this persona which allows us to have a perfectly nice Interview conversation! [laughs]

DRUKMAN: How did you finally learn to cope with your shyness?

ALBEE: The same way I coped with my fear of flying. I went out to Coney Island one night and went on every single thing that terrified me. The parachute jump, roller coasters—everything that scared me—over and over again.

DRUKMAN: I used to be afraid of flying, too, and I would have to get tanked up on booze before I got on that plane.

ALBEE: I used to do that, too, but now I’ve stopped drinking and can’t do that anymore. [laughs]

DRUKMAN: Drinking must have helped you overcome your shyness.

ALBEE: No, because I was never interviewed drunk. I wasn’t a very happy drunk. I felt the responsibility of telling everybody how they should be living their lives. I found anybody’s hopeless weakness, and I would just zero in on it and publicly humiliate people. I was awful with alcohol.

DRUKMAN: I always strangely admired people who could zero in on someone’s weakness. It shows an insight, at least.

ALBEE: Oh, complete insight, but mercilessness. A little mercy is nice now and again.

DRUKMAN: Can you tell me my one weakness?

ALBEE: One? [laughs] Probably, but they say the true sadist is the person who will not satisfy the masochist.

DRUKMAN: [laughs] Yep, you spotted it! OK, last question: Any advice for young artists?

ALBEE: Well, I always tell my playwriting students that if there’s anything else you can do with your life that will make you happy, give up playwriting.

DRUKMAN: Really?

ALBEE: The economic pressures on the playwright now are worse than they ever were, and what the audience wants is so different from what a serious playwright wants. I exaggerate this, but it’s very tough. The trouble with being a playwright is you’ve really got to know if you’re compromising, you’ve got to know if you’re selling out, got to be able to figure that out. And then you mustn’t end up with terrible regrets of having sold out, because you’ve decided to do it for a buck rather than posterity. It’s a tough racket.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 2002 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.