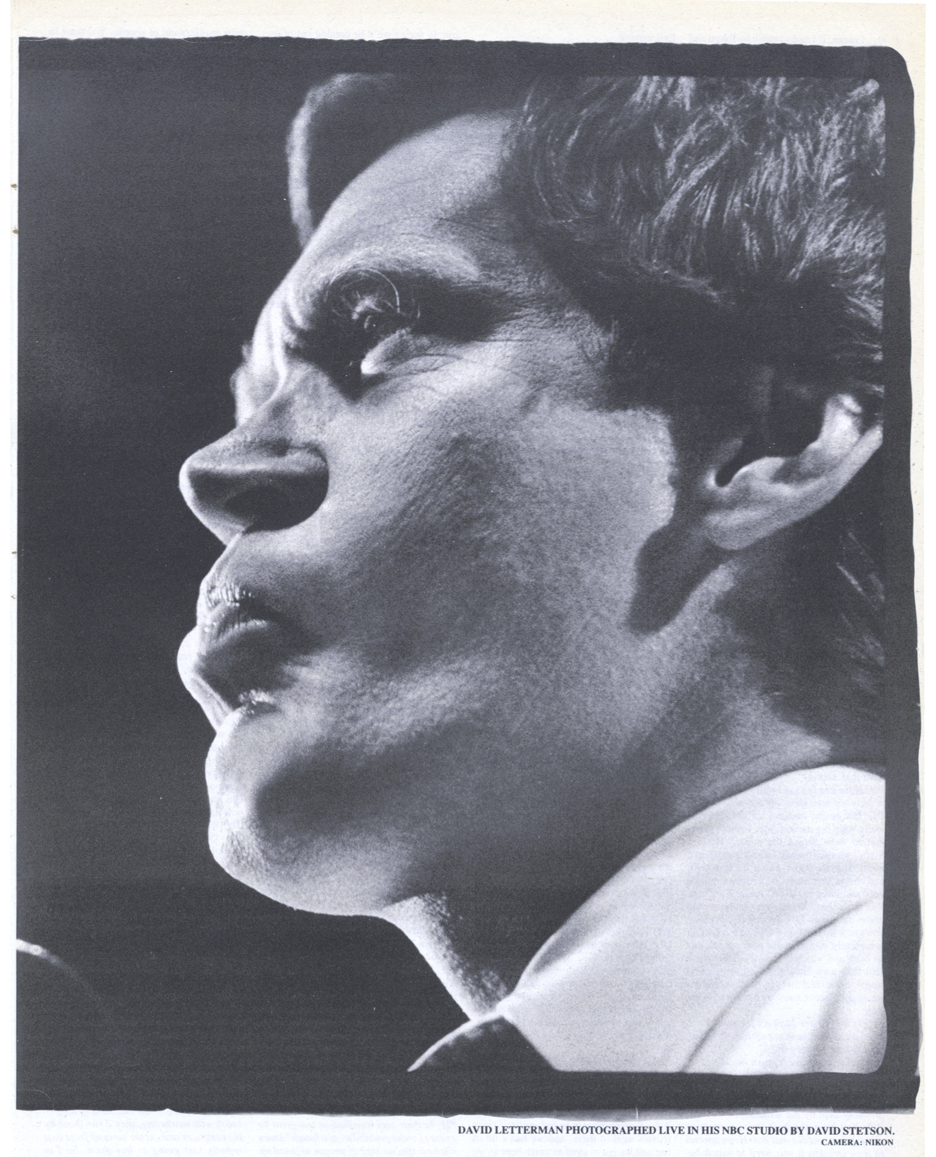

New Again: David Letterman

In 1984, David Letterman was three years into his residency at NBC in the prime Late Night slot—the one that Jimmy Fallon recently handed down to Seth Meyers. This was before he was passed over for Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show gig when the NBC execs chose Jay Leno as Carson’s successor, before the infamous televised feud emerged between Letterman and Leno, and before Letterman became a fully-fledged household name. Then, he was just Dave, rowdy, young, late night talk show host and former stand-up comedian with a penchant for gag segments.

When Pat Hackett interviewed Letterman for Interview’s September 1984 issue, Letterman was inviting then-promising young newcomers Howard Stern and Jerry Seinfeld on his show, combating nerves when meeting Bob Dylan, and taking cues from former girlfriend and original head writer, Merrill Markoe. On the edge of a career about to explode, Letterman dismissed the idea that his unique brand of comedy would ever catch on commercially, “that ain’t gonna happen.”

It’ll be Letterman’s 67th birthday on Saturday, officially 30 years since that interview, and the late night fixture has announced his plan to retire from nightly network comedy. Though the Letterman we see today is a much more polished, established personality who wears suits and counts Julia Roberts as a close personal friend, he’ll leave his show at CBS much the same way that he entered it at NBC in 1982: still rattling off his Top 10 at the start of each show, and with Paul Shaffer by his side. —Kenzi Abou-Sabe

David Letterman

By Pat Hackett

“From New York City, the birthplace of dress slacks… Where the cabs are yellow and the drivers aren’t… It’s Late Night with David Letterman, And now, here he is… NBC Employee of the Month… a man who likes to have a beer with his roadies now and then… David! Letterman!”

Dave enters the set with the infallible beat of Mr. Paul Shaffer’s band behind him. He scans the studio audience and determines, “We’ve assembled a lovely group of humans here.” He turns to his announcer, “And what do we have for them, Bill? That’s right! They’re all going home in a brand new Plymouth Horizon!” Letterman fills the hour time slot following The Tonight Show, and fills it, he points out, “dirt cheap,” with such low-budget features as “Small Town News,” “Bad Phone Calls,” “Brushes with Greatness,” “Stupid Pet Tricks,” “Stupid Human Tricks,” “Viewer Mail,” and “Dropping Stuff Off A Five-Story Building.” And now, if you’re anything like Dave finds he is, and you “just, can’t get, enough, Celebrity Information…”

PAT HACKETT: I’d always assumed you did a lot of editing to get your show as sharp as it is, but then when I went to a taping a few months ago, I was surprised later that night to see that the show ran with absolutely no editing at all.

DAVID LETTERMAN: We very rarely edit. Other than just audio bleeps, which we do all the time, I would guess we’ve done less than half-a-dozen edits in two-and-a-half years.

HACKETT: Do you watch the show at home at night?

LETTERMAN: No. If I feel something’s gone badly, I’ll watch the tape immediately after the show. But not at home.

HACKETT: What vintage TV shows did you look at for inspiration?

LETTERMAN: We looked at some early Steve Allen shows and some really early Ernie Kovacs—a two-hour show he did from Philadelphia in the morning. It was on some sort of a limited network—four or five Eastern cities. One thing the shows we liked all had in common was a casual kind of liveliness, an un-slick, see-the-camera-cable/see-the-mistakes kind of thing. See, what we try to do is pure Television. We’re at opposite ends of the scale from Dynasty. We go into the studio, use the cameras, invite people in—we do a television show. Whereas what most other people do is produce things to be shown on television, but they’re not Television—they’re dramas, comedies, musicals, whatever. They’re at the slick end of things and we’re at the bargain basement end.

HACKETT: Your show is heavily music-oriented. Paul Shaffer’s band is prime, the musical guests are great. So I’m curious about exactly what your own taste range is in rock-‘n’-roll. Let me put it this way: which death hit you hardest—Buddy Holly, Elvis, Jim Morrison, or John Lennon?

LETTERMAN: Well, it was Lennon, obviously. I fell in that generation. You know, my sister’s four years older than I am and probably would say Elvis.

HACKETT: But I’m a little younger than you, and still it was Elvis that really put me away.

LETTERMAN: I was not a big Elvis fan in the beginning. But right after that—the girl groups and Motown and the Beach Boys and then the Beatles–that was it for me. Those elements. The first song that I remember really hitting me was “He’s So

HACKETT: So ’63 was your rock-‘n’-roll-awakening… Now I have a complaint: because I’m a big Dylan fan, I object to his appearing on your show and just singing, not talking. It was too disappointing. I’d rather not have it at all.

LETTERMAN: Yeah, I know what you mean. It would’ve been great if the guy had at least said, “Where can I get a hot meal at a fair price?” But… I was so nervous that he was even in the building, let alone on the show! And for two days it was negotiations–“He’ll do this, but he won’t do that,” and finally about an hour before the taping they said, “He’s thought about it and he doesn’t want to talk.” So what could we do? We didn’t want to jeopardize the whole thing.

HACKETT: Well, if Bob’s any kind of man he’ll come back and favor us with a few words or do a “Stupid Human Trick.” I was just reading the Rolling Stone interview with him, and for some curious reason it goes on and on grilling Dylan on how he feels about abortion! And so Dave, maybe we should know how you feel about prayer in the public schools? Racial quotas? Yes? No

LETTERMAN: My political position is that I’m happy to be alive and in North America.

HACKETT: On of the most popular segments on the show is “Stupid Pet Tricks.” And I could see that you really loved the dog who could go to the store, buy a six-pack, and carry home the beer and the change in his mouth.

LETTERMAN: Oh yeah, that was great, great. I like the animals more than the people, sometimes. But what you have to understand there is that somebody taught him how to do that. So what are we looking at? The result of 90 days of intensive training? Here’s a guy who’s spending his life teaching his dog how to buy him beer!

HACKETT: Do your own dogs know any “Stupid Pet Tricks”?

LETTERMAN: No… Well, actually, yeah. They each know one trick. My girlfriend Merrill Markoe,” Stupid Pet Tricks” was her idea—she was the head writer on the show for about a year—and we have two dogs, Bob and Stan. Bob and I sound the same when we eat potato chips. That’s Bob’s trick. And Stan’s trick is that if you read him a list of TV comediennes he’ll only get excited when you reach the name “Lucille Ball.” The key word there is, of course, “ball.” He loves to play ball.

HACKETT: The phone calls you make on the air are so trouble-free. Do the people you call know in advance? Or are they just all so cool?

LETTERMAN: We do arrange things in advance. Otherwise the whole show would be dialing and arguing with operators. We’ll read an item about somebody in, say, Montana that looks interesting, and our staff will call them the day before and ask if they wouldn’t mind talking to us on the air. The person may or may not know what it’s going to be about. Then that afternoon we’ll call and say, “It’s going to happen in a couple of hours,” and then minutes before the show we’ll call again and say, “It’s coming up in a minute, so keep your line clear for us.” Stuff like that. It used to be that you could just pick up the phone on the air and call anybody. Steve Allen used to do that. But because of his show, the rule was made that you had to use an intermittent beep sound while you talked, but they did away with that. Now you just have to get the approval of the person you’ll be talking to.

HACKETT: That’s interesting.

LETTERMAN: Just barely, I’m afraid.

HACKETT: No, it is! Everybody wonders about all this.

LETTERMAN: What you do find when you make these calls is that people handle themselves with a great deal of poise. That’s always reassuring to me for some reason, when you get someone on the phone and he just comes to life telling you about things out there in Montana. It makes you feel good about the country, somehow.

HACKETT: I loved that time when you called five random people in South America and asked them if they had any Julio Iglesias records—to find out if he was as big there as he claims he is.

LETTERMAN: Well, in that case, we only told them that we were an American television show and that we wanted to ask them a question and that the question wouldn’t be obscene. Depending on your feelings about Julio. We try to keep the calls as raw as possible.

HACKETT: Do you still go around to the comedy clubs?

LETTERMAN: I haven’t been in a long time, but members of the staff go all the time. When I was in L.A. that’s what I did every night for five years—go to the Comedy Store and work on stand-up. But then I just got tired of it. It was high school. You graduate and you don’t hang around anymore.

HACKETT: You said once that Jay Leno was a big influence on you.

LETTERMAN: That’s true. He’s a real cynic, and he can cut right to the core of why something’s stupid and show you why it’s just so funny that it’s that way. He and I got to L.A. about the same time, although he’d been doing stand-up a few years before that, and when I saw him I thought, “Oh, yeah. This is the way it ought to be done.” We had a guy on last night, Jerry Seinfeld, who’s also very good, very smart. I like them because they’re observational.

HACKETT: What about the older guys as influences? Like Lenny Bruce, say.

LETTERMAN: He made no impact directly on me. I guess Lenny had less exposure where I was, in Indianapolis, than he did in places like New York and Chicago. The first comedy records I bought were Bob Newhart and Jonathan Winters and later the Smothers Brothers.

HACKETT: Did your time here at NBC—in this great building in Rockefeller Center—overlap with any of the original Saturday Night Live period?

LETTERMAN: No. We went on the air in June and they had done their last show in May. So I missed all of those people. It is a great building, though, isn’t it? Physically, it’s a kick just to walk around in it every day.

HACKETT: Those Saturday Night Live people were truly big talents, of course, and like everybody else I loved them, but the one thing I don’t care for is that they dish it out, but they never dish it out to themselves. I mean, if they’re going to go so far as to make jokes about the girl who’s been in a coma for years—saying that moss was growing on the north side of her head or something—then when Belushi died, where were all the gross jokes? Instead they were so reverent, they said, “We’ve lost a fine man.”

LETTERMAN: I know what you’re saying, that if you’re going to ridicule, it should be across the board. Well, we do make fun of people a lot on our show, I guess, and I’m sure I’d be the first to get bristle if somebody was making fun of me like that. …But it’s… You do it and you know you shouldn’t do it, but… I don’t know. It’s human nature, I guess, to try and get away with it.

HACKETT: To me, though, your show dishes it out in a milder way. It’s like an undercurrent of ridicule, but mixed with an odd sort of appreciation. You think, “He must like these guests, because who else would get them on television?” I mean, maybe you only appreciate them because they are ridiculous or eccentric, but at least it’s appreciation. Otherwise they’d be ignored.

LETTERMAN: A lot of the stuff isn’t even intentional. We used to get a lot of heat from people who said we were making fun of foreigners, but it’s just that when you go out inot New York City to talk to small business owners, you don’t find many Americans anymore. All the retail shop owners are brand-new Asians, Arabs, whatever, and to me what they do is amazing. I mean, if I had to move to Tokyo and open up my own show store… Jeez, can you imagine going to Cairo and saying, “Yeah, I think I’ll open up a gift shop…” They get the inventory and they earn the language and they get right to work.

HACKETT: What did the ancient “letter-men” do for a living? Mailmen? Sign-painters? Scholars…?

LETTERMAN: Not scholars, surely. Jeez, I don’t know. Maybe they helped Gutenberg set his movable type.

HACKETT: When people get successful and their disposable income starts to soar, they start having “collections.” They go antiquing and art collecting and they find all these outlets for their mad money. What do you do with yours?

LETTERMAN: Jeez, I don’t know. I don’t live high in any regard. But let me just say that I do give plenty of money to charity so people won’t scream, “That asshole!” But, jeez, I don’t spend my money on anything much. I wish I could spend it on travel, and I guess I could, but I don’t, so… I’m reading this William Shirer book now. When he was fired from the Chicago Tribune he and his wife took a year off and lived in a tiny little fishing village on the coast of Spain. North of Barcelona. Now, doesn’t that sound like just a keen thing to do for a year? The whole notion is really appealing.

HACKETT: But do you think you could really do it?

LETTERMAN: I don’t know. I find that I enjoy myself on vacations, so that’s a start… “Stop The Presses! He Enjoys Vacations!”

HACKETT: The writers and artists and prop people on your show conceive some great quasi-modern consumer inventions like toasters for croutons and rotating granola dispensers for hikers. Do you think that if you were back in the old days that you could survive without the refinements of civilization, like on the open range?

LETTERMAN: No. I’d be one of the first to go down. Although I do think that if I were in some kind of prison, that I could break out. I have that notion.

HACKETT: Have any big stars that you’ve wanted to have on your show eluded you?

LETTERMAN: Not really, because we don’t necessarily want big names. See, I would guess that to most shows the name “Howard Stern” wouldn’t sound like a big catch as a guest. But we had Howard on last night and he has an attitude, he’s ready to go, he gets audience reaction. Andy Kaufman was like that. Whenever Andy would come on it was like a vacation, because you knew he had taken care of everything completely, so you could pretty much just sit back and watch it. Pee-wee Herman is also that way. He’s unbelievably professional. So we feel that you do not automatically get a better guest by having a bigger star.

HACKETT: Is the “Viewer Mail” all for real?

LETTERMAN: Oh, yeah. Those are absolutely letters people have written to us.

HACKETT: Do you get much mash mail?

LETTERMAN: I don’t know. The mail is all handled by the people who do the “Viewer Mail,” and I think if I get any really hot mash mail it’s probably kept by the writers.

HACKETT: You have the best writing on your show. When you did that Bob Hope special in New Orleans it was hard to watch because you had to say such awful lines that were—

LETTERMAN: Stop! Let’s not even talk about that. On to something else. Pleeease. I thought I was over it…

HACKETT: Sorry. How did your show wind up with Carson’s company?

LETTERMAN: Johnny Carson in one of his contract negotiations with NBC got approval of whatever show followed his Tonight Show. So that manifests itself in a production credit. But the only contract is that they have a man who’s a liaison between the two shows who makes sure there’s not a duplication of guests.

HACKETT: On your official bio you listed Viva Las Vegas as your favorite movie. However, on the air you blurted out a recommendation to go see Terms of Endearment.

LETTERMAN: Oh, yeah. Although my girlfriend walked out of the theater, upset that she’d spent her money on it. And I’ve heard other people who’ve read the book say that it’s “cheap emotional manipulation.” But see, that’s all I’m lookin’ for, is cheap emotional manipulation. I was sobbing.

HACKETT: Did you cry? Really?

LETTERMAN: Oh, just embarrassingly. I left the theater and felt melancholy for days, and afterwards I thought, “This is great. I feel so much better.” So to me, that’s worth the price of a ticket. I heard Pauline Kael whining away on some radio show about The Natural, saying it’s an old-fashioned movie for people who don’t go to the movies very often. But again, I loved it. Again, not having read the book. It’s a universal fantasy. You’re watchin’ a ball game and you’re 37 years old and you say to yourself, “You know, I bettcha with a coupla days’ training I could probably knock one out of the park…” Even when you’re playing Little League, in your mind you’re in the World Series and it’s the bottom of the ninth and there’s a man on second and two outs and all you need is that line drive to score… The Natural just plugged right into those fantasies for me. And I liked that it was so simple you could take it superficially or you could think about the symbolism, and there again, I cried. And again I was happy. Then I heard this Kael woman just whining with such intense disdain in her voice about how awful this movie is, and every reason she gave that she liked Indiana Jones was every reason I liked The Natural. She said it was boyhood fantasies. You see, I’m conscious of people whining because I do it all the time myself. Like Burt Reynolds. I mean here’s a man who’s worth, what? 50 million? And he’s always somewhere whining?

HACKETT: Well he—

LETTERMAN: Yes, I know. He desperately wants a child! Now what is the deal? Burt can’t get a date? Find a girl, Burt. Get outta the house!

HACKETT: It’s the biggest gimmick in the world, this elusive dream of paternity.

LETTERMAN: But see, America loves that. I used to think nobody bought that stuff, but I was so wrong. They love it, they care about it, it’s a great diversion.

HACKETT: Well you could take a lesson from that if you ever want to get huge, huge in the American consciousness.

LETTERMAN: No, that ain’t gonna happen…

HACKETT: Your daily schedule must be packed.

LETTERMAN: Yeah, I’m having a breakdown. I’m getting sick of it… No, I get up and run every morning in the oppressive heat and humidity because I have the strength of 10 men, and then I drive to work and we have meetings and then rehearsals… But I get ten weeks vacation and it’s not that tough, it’s not like carrying a hod full of bricks, so…

HACKETT: Aside from being a TV weatherman in Indianapolis before you struck out for L.A., what are some other jobs you’ve had?

LETTERMAN: In high school I had a great job at the Atlas Supermarket in Indianapolis. All my friends worked there, and we had a lot of fun and we got to steal as much beer as we could. I worked there for three years sacking groceries and pricing cans and working in the butcher department and checking out groceries. Looking back, it was on of the best jobs I ever had.

HACKETT: You displayed some of your bagging prowess on the show when you challenged the winner of the National Supermarket Bagging Contest to come on and—

LETTERMAN: Yeah, I thumped that kid, didn’t I? Because I’m very good at bagging. I bag groceries every Saturday at my market, and people get annoyed because they think I’m trying to screw somebody out of a tip. But in actuality it’s recreation, that’s all.

HACKETT: Are you nostalgic about anything besides the Atlas Supermarket?

LETTERMAN: In the springtime, especially, I get very nostalgic about going back to Indiana. In spring we’d be coming out of one of these horrible Midwestern winters and school was just about out. And everything there just turns kind of a neon green very early and it smells so great, and it’s just every pleasant association that a kid would have. Even now, I’m hopin’ to go to this weekend. It’s always fun for me to go there.

HACKETT: Your whole family still lives there?

LETTERMAN: Those that are alive, yeah, except my younger sister, who works for the St. Petersburg Times. My mother lives there, and my other sister’s family. So it was not a big family to start with.

HACKETT: On the show the other night one of the guests brought up that your college fraternity was Sigma Chi and you changed the subject really quick.

LETTERMAN: Yeah, I was a Sigma Chi. I am a Sigma Chi. It’s one of those deals where you join it for life. It’s not that I’m embarrassed about it, but it’s just like somebody saying, “Didn’t you play freshman volleyball in high school?” and you say, “Well, yeah, I did, but I’m 37 now, so…” It was fun, it was great social maturation for me—or thwarting of social maturation—but, you know, we’d just drink as much beer as we possibly could and sneak as many girls as we could into the fraternity house, and we’d make fun of the people who lived in dorms, and that was it. For some people a fraternity does become a lifelong center of business contacts. They’ll call you up from Phoenix and say, “Well I was a brother and so on and what do you know about the Henderson account?” It’s a big network for businessmen, but I never really fit into that. I mean, I don’t go to homecoming and I didn’t marry the Sweetheart of Sigma Chi.

HACKETT: But I keep forgetting that you actually did get married in college.

LETTERMAN: Got married when I was 21. I finished my senior year while I was married.

HACKETT: It’s hard—

LETTERMAN: Yeah, it was hard.

HACKETT: I was going to say it’s hard to imagine.

LETTERMAN: It’s hard to imagine, and it was very difficult , also.

HACKETT: So why did you leave Indianapolis with the beautiful springtime?

LETTERMAN: I was too unhappy with myself to stay there. If you’re secure with yourself, then regardless of where you are, you’re happy and you lead a productive life, and have kids and go to Rotary meetings and you have, you know, just a great life. But if you’re insecure like me and millions of other young airheads, you move to Los Angeles and entertain drunks in bars. Or try to.

HACKETT: When you left, was it with the intention of going into stand-up comedy?

LETTERMAN: No. When I left I thought I would be a writer, because it was easier to explain to your family than—”What? You’re going to be a circus performer? What? What’s he doing?” And then I found I didn’t have the patience to be somebody who gets up and really writes. So the quickest way to any kind of reinforcement was working at the Comedy Store—I’d find out immediately if I was funny or not.

HACKETT: Is there any humiliation too great to endure for the possibility of a laugh? Does it take a special kind of person to stand up there and go through that?

LETTERMAN: Well, certainly not “special” in the sense that Mother Theresa is special, but… I have a crude theory that I’m sure is not true, but I base it on the people I was hanging around with night after night. I think it’s either people who did not get enough attention as kids or kids who got way too much who go into comedy.

HACKETT: So did you get too much attention or too little?

LETTERMAN: I got too little. I clearly got too little. But comedians by and large are not fun people to hang around with. They’re dejected and depressed and sullen and nasty and back-biting and jealous, and I’m right in there, I’m included. You don’t want to spend any time with me, either. But they all have that one desire in common—to draw laughter out of people. You want to show that girl in high school who wouldn’t give you the time of day, “Look what I can do in front of 200 people. I can get them to laugh! You wouldn’t go out with me back then, and I was getting Ds in Shop, but…” And I think that’s probably the motivation.

HACKETT: But does that ever really work? Doesn’t it turn out that the girl you couldn’t date is still absorbed with her own world and she doesn’t even know…

LETTERMAN: Oh, absolutely. You’re setting yourself up for—”What? You say you’re on television? Why no, we hadn’t heard.” Sure, absolutely. You can’t win.

HACKETT: You’re more introspective than you seem on TV—not that there’s a lot of time for introspection on national television.

LETTERMAN: It’s because all comedians are preoccupied with one thing and with one thing only-themmm-selllves. It’s a horrible lot in life.

HACKETT: Then what about actors? At least comedians are funny. Actors are comedians without the laughs.

LETTERMAN: Oh, please…actors. I like it when actors go on shows like Entertainment Tonight and talk about how their characters have “grown.” I actually heard one sitcom actress—Carson asked her what was different about her character, and she said, “Well, this year, she’s getting her hair cut.” And I thought, “Yeah! Yeah! Let’s tune in to see that! She’s going to have, what? Shorter hair? Oh, my God!” And she said it like, “We’re really startin’ to get this character pinned down on the hair issue.”

HACKETT: I love it when they say their characters are “rediscovering their own sexuality,” But, uh, have you ever gone for therapy? Sought “professional help”?

LETTERMAN: Yeah, yeah.

HACKETT: Yeah?? Really?

LETTERMAN: Yeah, there were two periods in my life when I went to see a therapist, and it came down to that I would have to consider making massive changes in my personality, and I was reluctant to make those changes, so I said, “Nah, I’m done here, I’m fine now.” So I’m just as screwed up now as I was then.

HACKETT: Were you honest with them?

LETTERMAN: Oh, probably not. It’s like Sunday school. You want ’em to think the best of you.

HACKETT: How does your staff instruct the guests before they go on the show? Because last night one of them said they told him, “Don’t touch Dave.”

LETTERMAN: The guests can touch me all they want. In fact, many are encouraged to do so.

HACKETT: Which ones?

LETTERMAN: Oh, any of ’em. They can all touch me.

HACKETT: How do you feel about all the marketing surveys that’re done today? I ask this because a lot of the stuff on your show—like the segment called Dave’s Record Collection where you dredge up silly albums from the past like Telly Savalas singing, “Try to Remember,” and William Shatner doing a poetic reading of “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds”—all that kind of stuff—today with marketing, they’d run those by the computer and get the news up front that nobody was going to buy them. So I’m thinking that in 20 years, there’s maybe going to be a shortage of things to laugh at. I’m afraid marketing surveys will do away with all the good mistakes.

LETTERMAN: Will they really?

HACKETT: I don’t know. I’m wondering.

LETTERMAN: Well, I was always amazed at the number of Major Entertainment Figures who’d done things that just seemed to be so obviously silly. But then I think of the stuff that I myself have done—not that I’m a Major Entertainment Figure—but I sure did a lot of idiot stuff that could be held up to ridicule. But I think that’s true of anybody. You try something and it doesn’t work out and you say, “Well, I’ll never be doing that again!” But too bad, you’ve done it once and it’s already on record somewhere.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1984 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.