New Again: Anita Loos

Last week, Vanessa Hudgens stepped into the spotlight as Gigi on the opening night of the Broadway hit musical of the same name. Originally a novella by French writer Colette, Gigi focuses on the coming-of-age of a young Parisian girl at the turn of the 20th century. Hudgens inherited this role from a long line of female icons, including Audrey Hepburn and Leslie Caron, but Gigi‘s legacy began with Anita Loos and her 1951 Broadway adaption of the story. This week, we revive Loos’s spirit with a 1972 interview that explores her career, her travels, and her boyish hairstyle that took Paris by storm. —Johanna Li

Anita Loos: Gentlemen Prefer Genius

By Glenn O’Brien and Lillian Gerard

Not all the grand, glamorous ladies of Hollywood worked in front of the cameras. The great Hollywood studios of the ’30s were somewhat unique in that the only thing that mattered there was talent and a talented lady was right at home in a world that was not just a man’s world. One of the most talented ladies was Anita Loos who, though she was beautiful enough to stand out at the studio with more stars than heaven, was bright enough to shine behind the scenes as a top scriptwriter and studio executive.

Miss Loos was discovered by D.W. Griffith and began her career as a title writer. She was soon turning out scripts for Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. And by the time that movies learned to talk, she was one of the screen’s top writers. Irving Thalberg, the legendary mind behind MGM, discovered that this lady knew how to make a movie move so well that instead of assigning her one script, he assigned her everything, so that she spent the greater part of her 18 years at Hollywood’s top studio as the script doctor, a job which saved hundreds of movies from box office and artistic oblivion.

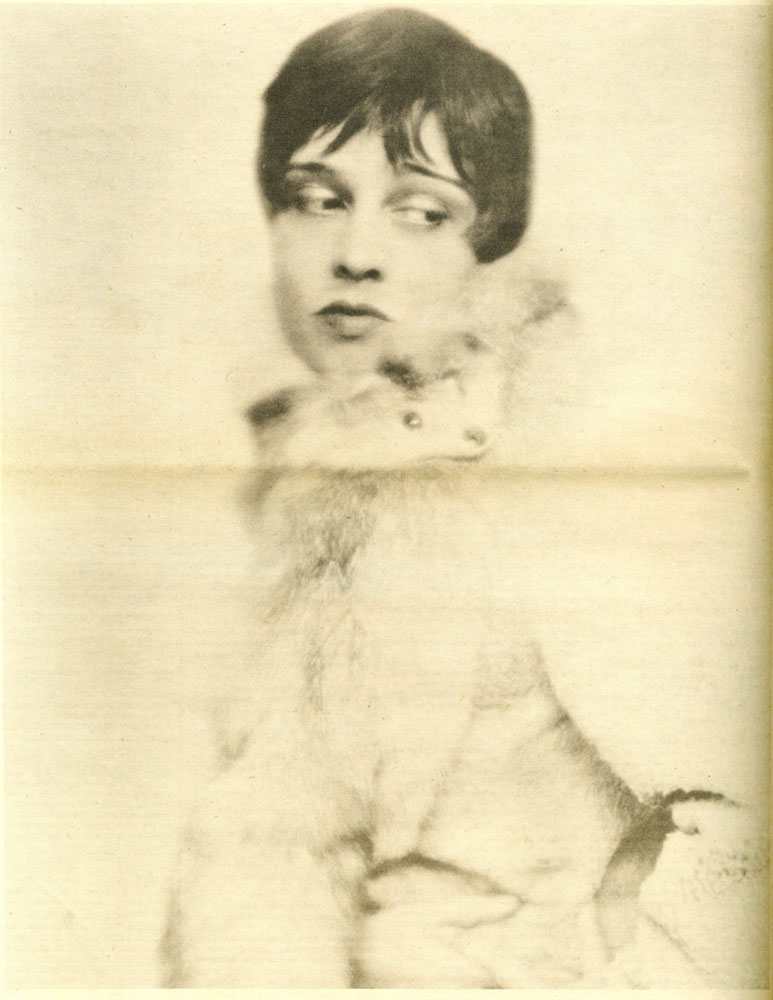

Miss Loos now lives in New York in a comfortably beautiful apartment near Carnegie Hall with her adopted daughter, a promising young dancer. She is surprisingly short but when seated in her little girl-sized rocking chair, her lovely legs propel her back and forth in time with her lively chatter and bright laughter. Although the accompanying picture was taken when MGM was in flower, Miss Loos is still very much a beauty in bloom. And when you leave her she leaves you laughing.

GLENN O’BRIEN: You’ve just written a book with Helen Hayes. What’s it about?

ANITA LOOS: It’s just about New York…the way it was when we were girls, the way it is now and the way we think it should be.

O’BRIEN: You speculate on the future?

LOOS: A little bit because the future’s right here in your lap.

O’BRIEN: How did you collaborate on the book?

LOOS: We had a hard time at the beginning because we’re two very different persons. Helen’s a do-gooder and I’m a do-no-gooder. She’s an optimist and I’m not. But we’ve been friends since the time we were girls and we’ve been through so much together…our girlhood here in New York when she was in show business and I was in the movies, then Hollywood when we were both at MGM. I was there for 18 years and she was there off and on. Then in recent years, we’ve gotten to see more of each other than ever. So we finally decided that this business of knocking New York is very unsophisticated and naïve. We’ve lived so much in Europe and we have so many European friends, and every European we know absolutely adores New York, can’t understand what there is wrong with it. And every New Yorker has gotten in this rut of repeating the old clichés as if New York were the only place in the world that has been beset by civilization. So Helen said to me one day, “Why don’t we write a book and try to open up New York to New Yorkers?” So we went to work and did it. And it took two years but it was such fun because we met people that we would never run into in our ordinary way of life. We had the most remarkable adventures. We spent one of the best days I’ve ever known on a garbage scow taking garbage down the river to Staten Island. We found out things about the way people live here that didn’t come into our way of life at all. For instance, those little Moran tugs that push all the ocean liners into the docks and push all the garbage to Staten Island, they’re the only place I know in New York where three times a day they have fresh bread baked on the premises. Each one has a chef and a kitchen the size of a table but I’ve never had such food. It’s like Dinty Moore’s in the old days! These men live eight days on the boat and eight days off. Another great thing that we discovered was that odors don’t cross the water. It could have been loaded with Chanel No. 5 but you can’t smell a thing until they dock. Then you smell it. And these garbage men were just divine! One of them was so good looking Helen and I immediately said, “He should be in the movies!” So we finally got to talking with him, he was tall and blond, and Helen said, “Do you like your work?” He said, “Yes, I love it. It’s out of doors. It’s great.” And they were skipping around and attaching this barge to a dock as if they were ballet dancers. And Helen asked him what he did on his eight days off and he said, “I drive a hack in front of the Plaza Hotel.” So I said, “Did you ever think of going in the movies?” And he said, “No, I’ve seen them in the park driving around. I don’t want to spend half of my life waiting for a little bit of action. I’d rather be out making it myself.” We really had a thorough education. We met probably the handsomest man in New York running a barber college. And going into the New York of the future, you can just see from the buildings what they’re preparing for. I don’t like them, but Helen adores steel and glass buildings.

O’BRIEN: Well she lives in the country, doesn’t she?

LOOS: Oh she lives in the country. And you know everyone says New York is the most dangerous place in the world to live. While Helen and I were working on the book, her house in Nyack was robbed of everything. And my other great friend Paulette Goddard has a chateau in Switzerland and day before yesterday thieves just wiped out everything. Here I am in New York, so far doing all right.

O’BRIEN: You said you went to a barber college in your travels. It reminded me that I was told you set the style in Hollywood of short hair.

LOOS: Well actually I did. I’d been trying to change my hairstyle and I’d discovered that my best feature was the shape of my head. So I went to a hairdresser and said, “Just cut it off so it shows my skull.” So he said, “It’s your order, don’t blame me for what happens.” He did it. I had it wind blown in the front and like a man’s in the back. Then I went to Paris and one of the first things I did was go to Lanvin to a fashion show. And I was sitting there with Norma and Constance Talmadge and a woman came up to me and said, “Madame Lanvin would like to see you.” We were three little girls from New York who’d never been to Paris before and I had no idea how Madame Lanvin would know who I was or what. So I went into her office and she said, “Where did you get that haircut?” I said, “In New York,” and she said, “Would you mind if I have one of the mannequins copy it?” I said, “No, go ahead.” So she said for one of the mannequins and her sketch artist and they sketched my head and the next day, that girl was in the Lanvin fashion show with this hairdo. The first wind blown bob. And it went over Paris like a tidal wave. It was shown every day in the Lanvin show and one night, I went to the opening night of the Diaghalev ballet with Nijinsky. And there I was, a little kid from New York, walking down the aisle and everybody turned to look at this hairdo. And at the same time Irene Castle was dancing at the Café de Paris and she’d cut her hair in a pageboy, so the two of us got together in Paris and started a wave.

O’BRIEN: I’ve seen pictures of you from the peak years of MGM and I could never understand why they didn’t draft you into being a movie star.

LOOS: I was born in the theatre. My father was a small time impresario on the West Coast and I was acting from the age of 7, but I started to write when I was 12 and by the time I was 14 I was making more money than I was acting. So I said, “Heck with that!” I wasn’t a very good actress anyway.

O’BRIEN: Didn’t Irving Thalberg ever twist your arm and tell you that you could do it?

LOOS: No, he was so glad to have a joke writer around the place. Joke writers were scarce and actresses were dime a dozen. He needed gags for those films. Griffith tried to make an actress of me. I was an actress when I first met him. He wanted to put me right into the movies, but at that time, my mother wouldn’t let me. She said, “You’re doing alright writing. Don’t press your luck!”

O’BRIEN: Did you start out as part of the New York literary scene?

LOOS: No, I was born in California. I never came to New York until I was writing films for Douglas Fairbanks. He brought me to New York for the first time. We all hated it in California. In those days we had to spend four days on the train to get there. We’d take our two-week vacation and spend eight days on the train just for a few days in New York. I only came here to live after Irving Thalberg died. I had spent 18 years writing there and when Irving died, I knew the jig was up. I said to myself, “This is the end of Hollywood movies.” I tried to leave immediately but I couldn’t because my contract had two years to go, so during that time, I wrote a play for Helen Hayes. Then I came to New York and I’ve never left. I very seldom go back to Hollywood.

O’BRIEN: How did you get the idea for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes? Was that a true story?

LOOS: Apparently it was a true situation. Otherwise it wouldn’t have been such a success. I was a great admirer H.L. Mencken’s and he was a good friend of mine. So I wrote the first chapter just as a joke because he had fallen for this silly little blonde. Just to kid him I wrote this chapter. I was writing movies at the time and never thought of it being a book or even being printed. I wrote it on the train going out to Hollywood with this blonde who’d made such a hit with Mencken. He wasn’t on board. Well, about six months later, I was in New York and I took down my suitcase and found this thing. So I sent it to Mencken as a joke. He read it and sent it back to me and said, “I think this is worth printing, but you’ve done a terrible thing. Do you know that you’ve made fun of sex? That is very un-American of you.” He said, “I couldn’t print it in the Monthly,” which he was running then “Because we have very pious readership. I think it should go in some woman’s magazine where it can get lost in the ads.” He said, “Send it to Harper’s Bazaar.” And I did and Harper’s really liked it and they got this illustrator Ralph Barton to illustrate it and then the most amazing thing happened. The second issue of Bazaar sold out the day it reached the stands. Suddenly liquor companies wanted to advertise in Harper’s Bazaar. And cigar companies. By the time it had finished in six monthly issues, Harper’s Bazaar had quadrupled its circulation.

O’BRIEN: You should go back to work for them. They could use you.

LOOS: Well everybody’s in trouble now. All the magazines. But then when it was published as a book…I had a beau who worked for Liveright Publishing and he said to me, “Would you like me to get out an edition for you to give your friends as Christmas presents?” I said I thought it would be lovely. Well they put out 1,500 copies and they were gone the day they hit the bookshop. And the second edition was 65,000 copies. It started out as a joke, then a serial, then a book, then it went into a straight play, a musical play, a movie, a musical movie, wallpaper, dress materials…everything.

O’BRIEN: Was the idea of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes stolen by Warner Brothers and put out in the Gold Diggers series?

LOOS: I think so. But everybody started copying it. Now they’re just getting ready to start it out again as a musical.

O’BRIEN: How many movies did you write?

LOOS: I wrote 200 movies that were produced before sound came in. I quit for a while then I came back after sound came in at MGM. I wrote the first picture for Jean Harlow. I stayed at MGM for 18 years, but what happened at MGM was that little by little, I developed into a film doctor. I was working on everybody’s films. I put jokes in everyone’s films. So after the first 12 or so that I wrote, I was more of an executive than a writer.

O’BRIEN: Was Dorothy Parker at MGM at that time?

LOOS: Yes, she was there for a while. Dorothy was lazy. She didn’t like work and she was contemptuous of Hollywood as we all were, except that I was contemptuous in a laughing way, it just amused me. But she didn’t like work and she did an awful lot of stalling. It’s too bad, she should have kept her mind on her job and turned out some movies. None of us considered them the least bit important. To me, the modern cult of old movies is completely unbelievable. D.W. Griffith hated movies. He was only waiting until he could get back to writing poetry and plays. And his poetry was awful and his plays were worse. There he was doing movies that are masterpieces and he had no appreciation of it at all. I wrote a hearty old thing called San Francisco and they must show it about three times a month on the late late show.

O’BRIEN: I saw it three weeks ago for about the fourth time and the same week, it was playing at Theatre 80 St. Marks.

LOOS: I wish I’d known. I’d have gone to see it, because on television they chop it up so.

O’BRIEN: Well in those days, Hollywood was producing almost 500 pictures a year…

LOOS: Well, Thalberg produced 52 pictures a year, and every single one of them was a smash hit. And what people didn’t realize was that those scripts took from two to five years to write. I was on San Francisco for about two years. We weighed every single nuance of every single scene to be sure that it progressed. I don’t think that movies today are a writer’s game. I think they’re a director’s game. I don’t think the written word is important in movies anymore and the really great movies are done by great directors who in many cases write their own scripts. I think it’s gotten to be more of a visual thing than an audible thing.

O’BRIEN: I heard you directed a scene in Red Headed Woman.

LOOS: I did direct a scene in Red Headed Woman. Just for fun. It wasn’t a scene at all. It was a shot of Jean Harlow on a merry-go-round on a pier. It didn’t require much direction. Thalberg’s directors weren’t very good because he made his scripts so clear that anybody could have directed them. Griffith didn’t use a script at all. He’d get out on set and extemporize. He always had a written story and dialogue but he took that and used it as a theme.

O’BRIEN: Did your job become harder when sound came in?

LOOS: It was never hard at all. I never took it that seriously. When I first wrote a sound picture, The Red Headed Woman, I had written stage plays so I was used to writing dialogue. When I told Irving I didn’t think I could make good, he said, “I’ll give you a guide that’ll show you the way.” He had an assistant who showed me the ropes. It wasn’t hard.

O’BRIEN: Was that the picture that Scott Fitzgerald started?

LOOS: Yes, Scott could never write a film. Isn’t that strange?

O’BRIEN: Why?

LOOS: Well, sometimes writers of no talent at all can write great acting scenes. Sometimes the very best writers can’t write scenes that come to life and Scott was just one of those. I think he got self-conscious. It was hard for me to understand. He wanted so much to be a movie writer, which was so utterly ridiculous for a man of his talent. The best movies we made on the lot were turned out by Frances Marion who wasn’t a writer at all. She just sat in conferences and made up stores.

O’BRIEN: Who were the other women writers?

LOOS: There was Vicki Baum. Lillian Hellman was there for a while and hated it. I don’t think she ever did much. Sylvia Levine was a fine writer. She’d been a writer of fiction. You know Lillian Gish says all the important films were written by women at that time. She decries the fact that women are not writing more films. She says that’s why films are so bad. But at one time, every important writer was at MGM and only about 10 percent of those writers produced anything. The others they would keep on contract until they discovered they couldn’t produce. But they tried them all. They could afford to. Thalberg had the greatest talent of never producing jealously among writers. There would be 10 writers on a script before it reached the screen, but nobody was disgruntled about it. He always made the plot the villain. It was the plot that was ruining the writing. We never cared.

O’BRIEN: Didn’t Thalberg quite often change the ending when the picture was nearly complete to a happier ending for better box office?

LOOS: He’d made all kinds of changes but most of them came after the previews. Sometimes he’d preview a picture and reshoot three-fourths of it, according to the effect on the audience. He was only licked once. When he tried to make Rasputin into a movie. Nobody could make a script out of that story. When he did get it out, it was a bad picture and he was sued by the Prince and paid out about five million dollars in damages. I suppose it failed because it required too great a writer to handle that subject. It required a Shakespeare or a Goethe and there was nobody on the lot who could come through.

O’BRIEN: Did you write any gags for the Marx Brothers?

LOOS: Yes! The Marx Brothers … that was something wonderful. I remember being sent down to the set one day because they needed a gag. I supplied a line and I think it was Groucho who thought a while and said, “Do you really think this character would say something like that?” As if a Marx Brothers character had any logic. But if a scene bogged down, the call would go out for some fast gags. I wrote The Women practically on the set. They were all ready to shoot when the script came back from the censor with practically every other page blacked out. They had an all star cast that had taken a great time to assemble so they couldn’t put it off to have a rewrite done, so Irving sent for me and said, We’ve got to get some laughs into this.” And they’d cut out all of what they called dirty jokes in those days. They weren’t dirty at all. So I sat on the set and wrote the scenes as Cukor shot them. Movie censorship was terrible in those days. I even knew of a case where a close up of a young mother with her baby had to be reshot because the censor said she didn’t have a wedding ring on her finger. It was The Red Headed Woman that brought on censorship. This girl who was very naughty ended up on top of the world, rich, famous and respected and the ladies clubs cracked down on the film. Because she was never punished.

O’BRIEN: What stars were your buddies?

LOOS: I was always close to Jean Harlow until she died. I did her last picture. And Crawford. I did a good many of Gable’s films. And Douglas Fairbanks before MGM, and Mary Pickford…

O’BRIEN: Did you know Garbo very well?

LOOS: I knew her as well as anyone will ever know Garbo. She is not to be known. One day she’s your best friend, and the next day she doesn’t know you. She’s fey. But she often came to my house in Santa Monica. She’d ring the bell and say, “Is anybody in there?” If there were, she wouldn’t come in. Otherwise, she’d come in and sit for hours. She’s exactly like some beautiful wild animal. If you pay her no attention, the first thing you know, she’s coming around and being very friendly, but if you make one move toward her, then she runs and you’ll never get close to her. But naturally for 18 years, I was right there on the lot with her and seeing a great deal of Aldous Huxley and his wife who were very good friends of Garbo. I knew all of her close friends. In New York, she’s very close to Madeleine Sherwood, Bob Sherwood’s widow. She’ll often drop in on her and do as usual, “Is there anybody here?” And one day, she came in and she was laughing. She had on slacks and a big floppy hat and she said some little boys had stopped her in the street and said, “You’d better look out, lady! You’ll get drafted!” That amused her, which is unusual because she doesn’t have that much sense of humor. She’s has a great sense of fun but she’s not a connoisseur of wit by any means.

O’BRIEN: Do you think she was born that way or fame made her so?

LOOS: I think she was born fey. There are people born full of fantasy, overemotional, too sensitive. I think she was always the same. I knew her brother quite well in London. He was a completely different character, very stolid and substantial.

O’BRIEN: Didn’t you introduce her to Stokowski?

LOOS: Yes! That was a bad move on everybody’s part. Stokowski was determined that there was going to be a historic love affair and you know what happened. They went away together and she walked out on him about the second week.

O’BRIEN: Were you friendly with Chaplin?

LOOS: Oh, yes because Paulette Goddard is still one of the best friends I have and out there, she was my closest friend. And she was Mrs. Chaplin at the time. We saw them every week. They would either come up to my house for lunch or I would go up to Charlie’s for dinner.

O’BRIEN: Buster Keaton is becoming more of a legend today.

LOOS: Yes, he’s come into his own. He deserved it from the very beginning. He was never appreciated. When I first went to work at MGM they had just hired Buster as a gagman and the reason they did was out of pity for him. He was down and out and nobody would make any pictures with him and he needed a job so Thalberg gave him a job as a gagman. But he was first recognized in Europe.

O’BRIEN: He was a surrealist before anybody knew about it.

LOOS: He certainly was. And he certainly didn’t know it. Buster was always as fey as he could be, and one reason he was very close to me and that he married the youngest Talmadge girl, Natalie, the one that didn’t act He had two sons by her, who now, work in the technical department in one of the studios. But Buster had no idea he was a great artist. I adored his pictures.

O’BRIEN: Did you know Fatty Arbuckle?

LOOS: I knew him very well. I think he was a really bad comic. His films were only based on the fact that he was fat. He never did anything funny. He wasn’t a comedian at all he was just a fat man. He played it for all it was worth.

O’BRIEN: I was always revolted by his pictures.

LOOS: He was a revolting man. He was a nasty man. He could make a child laugh though.

O’BRIEN: I understand you knew Tallulah.

LOOS: Tallulah was one of my very best friends. I gave Tallulah’s funeral oration at St. Bartholomew’s. After she died, Rex Reed called me up and asked me if I would do it and I said, “But that’s a terrible thing to ask! I’ve never spoken in a church in my life!” But I did it. I was with Tallulah from the time she first showed up in New York, and I was with her in Hollywood when she was with Twentieth Century and I was with her in London when she was acting over there. I knew her up until the time she died.

O’BRIEN: Why didn’t she make more movies? She was such a wonderful star.

LOOS: I don’t know if her movies were successful. I have a feeling that they weren’t. What films have you seen of hers?

O’BRIEN: I think just two. Lifeboat and The Devil in the Deep with Gary Cooper and Charles Laughton in what might have been his first American picture, and Cary Grant who has about two lines.

LOOS: I know that Lifeboat was not a success so it may be that she didn’t catch on. But you know Garbo was not a Hollywood success really. Her pictures never paid off in this country. The money they made was in Europe. They were just trying to get rid of her contract at the time she quit because the war had ended that market.

O’BRIEN: Is that why she quit?

LOOS: No, she quit because she had a terrible picture The Two Faced Woman. Did you ever see that?

O’BRIEN: Yes. It doesn’t seem that terrible, but I guess in terms of her career it was.

LOOS: Yes, she was so sensitive. It really ended her. She said, “I’ve had enough now.” She had all the money in the world. She had all the money they ever paid her. She wouldn’t even pay her agent. Her agent worked for no percent. She was in the hands of Salka Viertel, you know, and Salka decided this was going to be a great story for her and I suppose George (Cukor) just went along with it, because Garbo wanted to do it. She was a headache to the studio. They weren’t sorry to get rid of her. Nobody knew where she lived. They didn’t have a telephone number for her or anything. The only person who could reach her was Salka Viertel, and that’s why they put her on salary at MGM.

O’BRIEN: Do you ever go to the movies now?

LOOS: No, I’m waiting for Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm to come back. No, I’ve seen two movies that I simply adore recently. The Sorrow and the Pity I think is a great, historic movie. I think the technique of that movie, telling a colossal story in close-ups of personalities concerned with it, it’s just about the most staggering technique that has been devised. He must have looked at billions of feet of film. And then I absolutely adored a picture called The Murmur of the Heart. That’s the most intelligent picture of modern life. Its placement of sex is just where it belongs. I loved The Garden of the Finzi Continis too, that was wonderful in a classic way, but The Murmur of the Heart was quite unusual. It’s the best modern film I’ve seen. It treated sex as a joke. After I saw it, I went and looked up Zazie in the Metro, but that’s a little disorganized. I liked it enormously the first time but I didn’t like it so much the second time. But The Murmur of the Heart is so believable, and the whole thing which in this country would be utter, stark tragedy is just laughed off. To my way of thinking it’s the most civilized picture on sex that I’ve ever seen.

O’BRIEN: Have you seen What’s Up Doc?

LOOS: No, I simply loathed The Last Picture Show. I detested it. To like that film you’d have to be abjectly in love with Texans and I am not. I don’t want to know anything about them. I felt the way critics went overboard on that picture and then neglected The Murmur of the Heart made them a lot of yokels.

O’BRIEN: Critics want to discover something and now it’s very popular to discover Americana.

LOOS: And black and white film. I didn’t go to his new picture because I decided never to see anything by that director. And I don’t like diabolism so I stay away from things like Clockwork Orange. I think diabolism is awfully childish. I don’t even want to see The Godfather. I couldn’t stand seeing that horse’s head cut off. I wouldn’t mind if it were Marlon Brando’s.

O’BRIEN: Have you seen The Boyfriend?

LOOS: No, but I want to. I’m sure I’ll love it. There haven’t been girls like Twiggy around for years, not since Carole Lombard and Constance Talmadge.

O’BRIEN: Did you know Carole Lombard well?

LOOS: Oh yes. She was not only a beauty but a great wit. She was extraordinary. She was a lady, one of the very few ladies in Hollywood in those days.

O’BRIEN: I’ve heard some great stories about her pranks.

LOOS: She used to love go to up on Ventura Boulevard and thumb a ride with truck drivers. She was with a truck driver one day and he said, “You know, you look something like that movie actress Carole Lombard,” and she said, “Don’t you dare! Comparing me to that tramp! Stop this truck! I’m getting out!” And I was with her one day when one of the Hollywood’s best-kept men was walking down the street with a very tiny little dog. That was his daily stint, to take the star’s dog out. And she leaned out the window and yelled, “How do you like your work!”

O’BRIEN: What do you think of Women’s Liberation?

LOOS: The two most important executives I knew in the movies were Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish, and they did much better business because of their golden curls and other executives. Mary stacked up the biggest fortune anyone ever made in films and Lillian Gish knew more about lighting and camera technique than any man I know. She did it for herself. I have been done in by both men and women. I don’t have any preference. But I’m afraid they’re giving the gag away. I think women can get a lot further by covering up and going underground than by waving a flag. There was a big group of very beautiful lesbians in Hollywood, quite a number of them. I got dragged to a cocktail party one day and they were all there, done up in chiffon and hats and being very elegant. And in walked Elsa Maxwell in a suit with cuffs and a necktie and one of them said, “Oh look at Elsa! Giving it all away!”

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JULY 1972 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.