really good grades

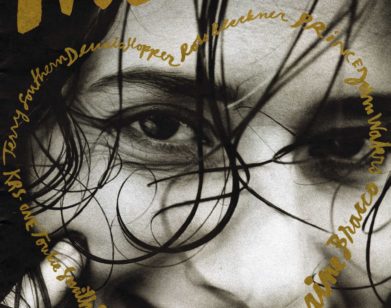

Nathan Fielder and Louis Theroux Teach a Masterclass on the Art of Awkward

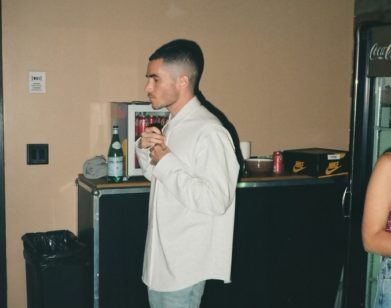

All Clothing and Holocaust Awareness by Summit Ice.

How to describe the work of Nathan Fielder? Even he, the salt–and–pepper–haired beau ideal of cult comedy, can’t quite put his finger on it. “Man,” he says, “after doing four years of a TV show, you’d think I’d be better at explaining what it is.” Allow us to try. Fielder—as he reminded us at the beginning of each episode of Comedy Central’s Nathan for You—“graduated from one of Canada’s top business schools with really good grades,” before going on to create and star in the wildly popular satirical reality series that found him lending real small businesses a mostly unhelpful hand. (In the show’s pilot, he convinces a frozen yogurt shop to sell a “poo” flavor, insisting the notoriety will attract customers.) As Fielder’s schemes become increasingly outlandish—advertising a pet store on the gravestones of a pet cemetery; creating a soundproof “sex box” so that parents can keep children in their hotel room while they get busy—the show takes on a surprising layer of humanism, forging earnest connections as Fielder fumbles his way through this competitive world.

Continuing his tradition of helping the masses with second-rate advice, Fielder is releasing a new comedy-reality series for HBO called How To with John Wilson. As the show’s executive producer, he will be handing over hosting duties to the titular documentary filmmaker, though fans will recognize the Fielderian stamp with episodes such as “How to Make Small Talk,” “How to Put Up Scaffolding,” and “How to Make the Perfect Risotto.” Following that, Fielder is taking his expertise to Showtime, where he will partner with the Safdie brothers on The Curse, a half-hour comedy that centers on a fictional HGTV show rattled by a mysterious curse. It’s the uncanny, meta manipulation of the reality television format that we’ve come to expect from Fielder, who has taken some notes from the cheeky British documentary filmmaker Louis Theroux, the face of programs including Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends, Louis and the Nazis, and My Scientology Movie. On a recent fall afternoon from his home in Los Angeles, this is Nathan for Interview. —SARAH NECHAMKIN

———

NATHAN FIELDER: Hi, Louis.

LOUIS THEROUX: Can you see me? I can see myself, but I can’t see anyone else.

FIELDER: Would you prefer to see me?

THEROUX: I’d like to see you, but I don’t want to rock the boat.

FIELDER: Thank you for chatting with me. It’s always a pleasure to talk with you.

THEROUX: Well, that’s nice of you to say, and it’s always a pleasure and an honor to speak to you. I’m such a big fan, as I think you know. The last time we spoke was in London and I’d had a couple of martinis, and I have a horrible recollection of making some joke about your Canadian accent. Afterwards, my wife Nancy said, “What is wrong with you?” But sometimes when I’m talking to people I admire, I get a bit silly. Apologies if I in any way caused you unnecessary embarrassment.

FIELDER: No apologies necessary, because I also recall that I tried to imitate your voice, and I’m sure I did a terrible job at that. But I remember Nancy saying that I got a few of your mannerisms right, and that really made me feel good. I’m not really a trained mimic.

THEROUX: I recall the mannerisms. I always get the impression that Nancy—if I may use a tennis analogy—makes line calls in favor of whoever’s my opponent, in a social sense. Maybe that speaks more about my own thin skin.

FIELDER: I think people do that with me, too. I’ve noticed that people will take other people’s sides.

THEROUX: It’s a wife’s job, in some ways, to know when to deflate you, and then, on rare occasions, to know when to pump you back up. That sounded like a kind of phallic image.

FIELDER: Well, it seems like you have a very clear idea of your wife’s job.

THEROUX: Good. Let’s talk about the big picture. You’ve got a new series that you’re exec-ing, and congratulations on that. I imagine most people who read Interview have a good idea of who you are and what you do, but for that lost soul who’s not been exposed to your work, how would you describe what it is that you do?

FIELDER: I will admit that one of the things I’m worst at is describing what I do. I made a show that was a comedy documentary series that involved real people, where I was helping businesses… Man, after doing four years of a TV show, you’d think I’d be better at explain- ing what it is. Can you help me out a little bit?

THEROUX: I’m about to. It may be a condition of your doing the kind of work that you do that you can’t express it too exactly, because if you defined it too precisely, maybe that would destroy something. And I can’t put it any better than that. We do know, as you say at the beginning of every episode—and I checked this on Wikipedia—that you studied business, or business management, or business… What did you study?

FIELDER: I ended up getting a Bachelor of Commerce degree, mostly because I felt like I tried everything else and that would be a good general education. But then, immediately after I got it, I went into doing comedy, and [the producer of the Canadian comedy series This Hour Has 22 Minutes] Michael Donovan hired me to do these correspondent pieces with real people. I had never done anything with real people before, but this was the job I was put in, and I was forced to figure out what to do and how to be interesting in that context. And then Nathan for You kind of evolved from there. I thought, “Well, business school was kind of absurd and uncomfortable, so I’ll satirize what I was taught on the show.”

THEROUX: It sounds like Michael Donovan might have occupied a similar place in your career that Michael Moore did in mine, that in embryo, you were working on short-form segments that you would then develop and expand on. Can you remember any of the pieces you did that you were proud of, or that you felt helped you understand what you could do?

FIELDER: Well, it was interesting because the show was screened every week for a live audience in Halifax, Nova Scotia. A lot of the people who would come out would be generally on the older side—50, 60-plus. So, in a weird way, I was almost conditioned to make stuff that would appeal to elderly people. Because it was screened for an audience, I noticed that people would laugh at things when the camera was on me that I didn’t intend to be a joke. At first, it’s humiliating to have people laugh at you when you’re not trying to be funny, but then you’re kind of like, “Oh, I guess these aspects of me are funny.” And then you weave that into how you approach things. Obviously, I can write jokes, but the moments I was always trying to chase were those that were inexplicably funny because they were human.

THEROUX: I just recently realized I’ve been doing this for 25 years, and in lockdown, I made a bunch of episodes that recapped some of my best moments. But looking back, it was striking to see what a tool I was. I don’t know if they use that term in America. I was kind of a dipshit. But what wasn’t clear to me was whether that was an obstacle or part of my gift. Sometimes, awkwardness or bits of transparent social hypocrisy can be very funny.

FIELDER: Yes. But when I watch you, I find you to be incredibly charming. Whenever I encounter someone who doesn’t know your work, I say, “He’s a tall, very affable British man who over the course of these documentaries is very good at narrowing in on the hypocrisy within people.” Are you offended by that description, or are you delighted?

THEROUX: I’m not offended by anything that can bring more eyes to the programs that I make. And I think that’s a reasonable characterization. But I’m going to reboot the conversation toward you.

FIELDER: Well, my tendency is going to always be to reboot toward you, because even though I feel the need to do these things sometimes to get attention for projects, I don’t like talking about myself.

THEROUX: Just to remind people, arguably your greatest hit, in terms of virality, was that you improved a business by modeling it after Starbucks, realizing that you could sail close to the wind on copyrights and make it look just like a Starbucks, as long as everything was “dumb.”

FIELDER: Yes, that’s right.

THEROUX: It was a brilliant idea. Before it was revealed as a segment for Nathan for You, some people thought that Banksy, the British street artist, was behind Dumb Starbucks.

FIELDER: I mean, they were selling the cups that we gave out. We handed out copies and people would list the cups on eBay for $500. When I came out and said it was me, there were a ton of cameras that came because they thought it would be this big event. It was kind of amazing because I gave this silly speech after, and I could see the disappointment on all the reporters’ faces. They kind of slunk down with their cameras and walked away while I was talking because they were expecting something grander, or a political statement, and unfortunately there wasn’t any. At that time, the news was so desperate for content that stories like that could actually happen. Now, I don’t know if stuff like that would get as much attention.

THEROUX: There are two main experiences when watching Nathan for You. One is hilarity. The second is a kind of cringe, a sense of embarrassment and awkwardness at how far you’re willing to push some of the ideas. I think your characterization of what I do was fair. You expressed some concern that maybe it would offend me, and now I’m going to be concerned that you might be offended by this, but I’ll say it: At the heart of it, what I see is a sort of artistic ruthlessness. I was recently reading a story about you in The New Yorker by Errol Morris, because you have a huge fan in the esteemed documentary-maker. And he said, in the context of a very complimentary piece, “It could be argued that many of Fielder’s attempts are mean-spirited… This has been a ‘problem’ with Nathan for You, this feeling of discomfort. Should I be watching this? Does it make me into a less- nice person?” And then he says, “Fielder will stop at nothing.”

FIELDER: Wow. You’re good at picking out the one sentence in an otherwise positive article. I think it’s fair. One thing I like about people watching the show is that they can make their own assumptions regarding how it must come about. I don’t like talking too much about the process and all that, because I’ve always liked the experience, as a viewer, of being like, “Should I feel good? Should I feel bad about this? How should I feel?” That’s the feeling that I feel a lot in my life in general, and I think that’s what the show is about. But I also think that sometimes people forget that this is a reality show, and during all these moments there’s a camera crew there. There are producers there. As uncomfortable as things may seem with me in the moment, ultimately this is edited together as a series of moments to tell a story.

THEROUX: For the audience to feel uncomfortable is not necessarily a bad thing. Avoiding awkwardness should not be the aim of comedy, because sometimes awkwardness is the funniest thing. If you own the embarrassment and make yourself okay with it, that’s very empowering. How do you find yourself in day-to-day life dealing with awkwardness?

FIELDER: Well, most social interactions are very uncomfortable for me. The sad thing is, there have been moments in the show when I’m actually trying my best to be charming because I’m like, “Oh, this is a moment where I actually want to get along with the person,” and it still ends up being very uncomfortable. Even when I’m trying my best, it’s not great. Everyone’s attracted to the people with very strong opinions, but I think a lot about the people who actually don’t know what they think, and are easily swayed either way, because I’m one of those people. That’s the zone I like to be in. And it makes sense that you empathize with a lot of the people on the show because most of them are very nice, sweet people. I don’t want anyone to look bad. I want to be the fool.

THEROUX: I think you succeed at that. Now, that sounded like a zinger, but—

FIELDER: You can zing me any time.

THEROUX: I feel like the show arrives at a place of extreme emotion at the end. I don’t want to give too much away. What can you say about it?

FIELDER: When Nathan for You ended, it concluded in a way that felt like a conclusion. Near the end of it, I was starting to feel the constraints, because I started off making it in a different headspace versus where I finished. When you start a show, there’s a lot of expectation associated with it that you’ve built or created. You’re always playing against expectations, because you have a fan base that watches stuff as it goes along and you’re trying to keep things surprising. Do you know the sitcom Roseanne?

THEROUX: Of course.

FIELDER: I watched it when I was a kid, but had never watched the pilot. And it was on Netflix at one point, so I watched the pilot. It was almost like a drama in how grounded the characters were. The tone was really interesting for a sitcom. My memory of it wasn’t like that, and I decided to go from that episode to one of the final ones, to watch what happened there. In one of those episodes, it was almost like a cartoon, where I think Dan’s grandma would sneak up behind the couch with a knife as if she was going to murder him from behind. And then he would turn and she’d act like she was doing something else. It was so cartoonishly over the top, and I think this happens with a lot of shows that go on and on—you keep playing against expectations for so long that you end up at a point where you have to go into total craziness to keep surprising people. On Nathan for You, we had to keep doing something different, because I never wanted us to repeat ourselves. Now, I’m working on new stuff that addresses more accurately where my head’s currently at. Actually, I feel like that was a huge tangent that didn’t answer your question. And I don’t know why I brought up Roseanne.

THEROUX: It was a perfect answer.

This article appears in the Fall 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Makeup: Latoya De’Shaun

Grooming: Frankie Payne using Oribe and Chanel at Opus Beauty

Prop Stylist: Nicole Roosien