GREEK LIFE

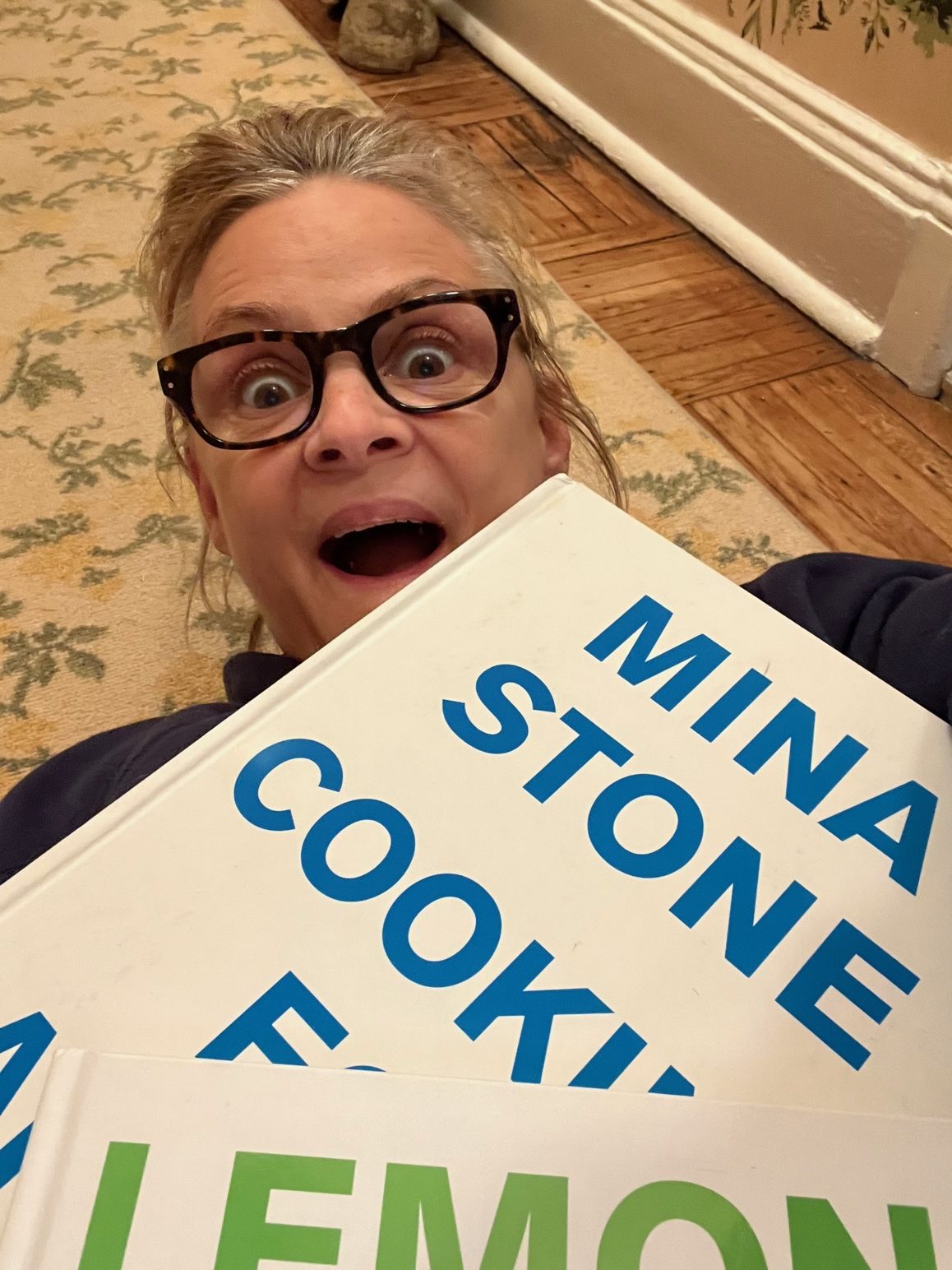

Mina Stone and Amy Sedaris Have A Big, Fat, Greek Chat

In a sparse, light-filled room on the ground floor of the former schoolhouse that houses MoMA PS1, you can find chef and writer Mina Stone at the helm of her eponymous taverna, Mina’s. The menu couldn’t be more different from traditional museum café offerings, which have historically elicited the same sort of ire from patrons that 90’s stand-ups levied towards airplane food. At Mina’s, museumgoers can expect Mediterranean small plates like fenugreek and sumac-dusted bread studded with golden raisins paired with a sharp, savory beet tzatziki. The stark walls and minimalist design call to mind both the whitewashed Cycladic seaside and a chic downtown gallery, both places in which Stone would feel at home. After all, Mina’s seems to be the perfect intersection of Stone’s cooking philosophy, decoded in her two books—2015’s Cooking for Artists and her most recent Lemon, Love & Olive Oil.

The former brought together recipes from her time as a chef working closely with the NYC art scene, most notably at the Red Hook studio of the artist Urs Fischer, with whom she collaborated on the book’s design and illustrations. For Lemon, Love & Olive Oil, Stone turns inward, weaving together Greek recipes, techniques, and stories passed down from her grandmother. What both of Stone’s own cookbooks share is a love for simple, artfully prepared food. So simple, even, that one recipe includes little more than the instructions for frying an egg, Greek style, in olive oil. Stone has found a kindred spirit in comedian Amy Sedaris, an unconventional cooking star and fellow olive oil enthusiast, who she sat down with for a conversation on all things Greek—from the best feta in New York to the subtleties of Hellenic hospitality.

———

AMY SEDARIS: Hey, Mina. You look really nice. What’s that behind you? I love your little knife rack. And cookbooks. That looks cute. This is your kitchen, I assume.

MINA STONE: There you are!

SEDARIS: There’s my book! [Laughs]

STONE: And that [painting] is the view from my grandma’s living room, which was outside, in Greece.

SEDARIS: I really like where you have it. It’s kind of crooked, and that’s really nice. Look at us, having a chit-chat. I’ll start off by saying, I got that feta cheese you recommended.

STONE: The Arahova one? What’d you think?

SEDARIS: Yeah. I like the other one more. The one that starts with a D.

STONE: Dodoni.

SEDARIS: I like the Dodoni. The other one was a little too salty for my liking.

STONE: Did you buy it in the plastic container?

SEDARIS: No. Fresh from Titan in Astoria. That grocery store.

STONE: And you still didn’t like it? Because when I get it and it’s in the plastic thing, I also think it tastes too salty. But when I get it from Titan, from those barrels, it’s really delicious.

SEDARIS: So I’m a big fan of your cookbooks, as you know. They’re so simple that even I can understand. I like looking and reading cookbooks, I very seldom follow a recipe. I kind of make what I make. Once in a while I’ll try something new, but I just have a hard time following recipes. But yours are really easy and the ingredients are so simple. I was like, “Who is this Mina?” We have a mutual friend, Adam Selman, and he’s like, “Oh my God, she’s a friend of mine.” We like picking recipes from your book and making them.

STONE: That makes me so happy. I was thinking as you were talking that when someone cooks a lot and they entertain a lot, which I know you do, I think that you end up using a cookbook as a source of inspiration, not to follow any recipes. You want to look at a cookbook because you’re like, “Oh, I could add that to my repertoire.”

SEDARIS: Right. Did you go to Greek church on Christmas?

STONE: I did not. My mother’s not religious at all. It is a huge part of her identity. She was a leftist, rising up against the dictatorship in Greece in the 70s. She really backed away from anything church-related. Much to my chagrin as a kid, because I wanted so bad to be a part of some Greek community in the United States.

SEDARIS: We went to Greek church, the one on 74th Street. My brother, David [Sedaris], said, “Do you want to go to the service on Christmas Eve?” And we were all like, “What?” We were always made to go to church. But it’s so different from our church. It put our church to shame. I don’t know the name of it, but it’s a megachurch. You know the one?

STONE: I do.

SEDARIS: It was thrilling. In North Carolina, ours almost looks like a high school production of something, a little bit tattered. But what I like about it is that all the icons that we grew up with are still there and some of the Greek people are still alive. It’s so homey. You have the blood-red carpet, and all the candles going, and incense. I just love the smell of Greek candles. The beeswax candles. I always have them in my apartment. And when you blow them out, it’s just that smell of Greek church.

STONE: It is a really nice smell.

SEDARIS: God. Nothing’s better.

STONE: It’s true. Your dad was the Greek one, right?

SEDARIS: Yes, my mom wasn’t Greek. The Greek church didn’t really accept her right away. But the women were very open, and that’s where she learned a lot of Greek cooking. She cooked a lot of Greek food, and we celebrated the Greek holidays, and our Greek grandmother lived with us growing up. It’s blurry to me. It seemed like 35 years, but it might have been just two.

STONE: Where were they from in Greece?

SEDARIS: This tiny village called Apidea.

STONE: Where was your mom from?

SEDARIS: Well, my parents were both from upstate New York, but my mom was English, Welsh, French, that combo platter. I learned cooking from my mom.

STONE: She just dove in and learned all the Greek food.

SEDARIS: My Greek grandmother did a lot of cooking in the house. She made kolokythokeftedes a lot. And I don’t know the name of the dessert, but you fry it. It’s really big, and I think you put cinnamon on it.

STONE: I think they’re called diples.

SEDARIS: But that olive oil cake you made me, that was really good. What’s the name of it?

STONE: Just “olive oil cake.” I didn’t learn it in Greece. It’s not a family recipe. It’s three different recipes combined, and then the sugar cut in half. And it lasts forever.

SEDARIS: So, I haven’t been to your restaurant. Where is your restaurant?

STONE: It’s at MoMA PS1 in Queens.

SEDARIS: Is it a full-on restaurant? Is it open at night, or during the day?

STONE: It’s a full-on restaurant, but it follows museum hours. It’s really for when you go to see the show. Some people come to just eat at the restaurant, but I do think the hours can make it tough sometimes. We’ve got a full menu. We went through a hard time, because we opened right before COVID. But now we’re having a lot of fun there.

SEDARIS: Do you have any favorite Greek restaurants in the city? I haven’t found the perfect Greek restaurant.

STONE: I don’t want to knock anybody’s restaurant, but it’s hard to find good Greek food in New York City, weirdly. This one place we go to in Astoria is called Stamatis. Amy, I think you would like that a lot. If you were to take your whole family, it’s just big tables, good Greek food. All the waiters are Greek.

SEDARIS: Oh, that’s great.

STONE: It’s very endearing to me.

SEDARIS: You bring the wine over, you uncork it, you just put it on the table, you serve it yourself. I love that.

STONE: I think about how that’s informed a lot of my cooking as well.

SEDARIS: Yeah. That’s the style I like. Come-and-get-it mentality. Or you put it in the oven, you walk away, you come back, and it’s ready. I like food like that.

STONE: I was thinking about my Greek heritage a lot recently, because I haven’t been going to Greece as much as I used to. And I was thinking about you, because I was thinking about how important your Greek heritage is to you. And you also don’t travel there, right?

SEDARIS: I’ve been twice, but I haven’t been since ’83.

STONE: Yeah, it’s alive through your family. For me, my Greek heritage was really tied in with going to the country. So I was thinking about how with Greek food, there’s this subtlety to entertaining. So much of Greek food can be made ahead of time and then as a host you can be a pretty chill human being.

SEDARIS: That’s what I like about it. Everything can be eaten at room temperature.

STONE: Yeah.

SEDARIS: I used to entertain a lot. And then I did the book I Like You, and then I stopped entertaining for large groups. Now it’s more one-on-one, maybe a couple people over. Everyone’s got these major food restrictions now. A lot of vegan people, vegetarians. It’s a lot of asking ahead-of-time instead of just coming up with whatever menu you want. I just like to make it easy and not have to ask anybody any questions. Like, “Come for dinner Wednesday.” It’s killed the dinner party in a lot of ways.

STONE: I think that if you go to someone’s house, it’s nice to just eat whatever they serve you.

SEDARIS: Right. I don’t like to bother anybody. I don’t want to have to ask, I just want to do it. So I’ll just have it all, all the options. I’m like, “Okay. Well, they can have some green beans.” Greek green beans are great.

STONE: It’s a great dish, I grew up eating it.

SEDARIS: The only thing I never nailed with Greek cooking is Greek potatoes, with the oil and the lemon and oregano. I just feel like I haven’t practiced with potatoes that much when I’m cooking Greek.

STONE: I never make Greek potatoes either. I think that I failed too many times. It is a really delicious thing when you have it, and it’s really lemony and salty, soaking up some sort of animal broth.

SEDARIS: I’ve only done it a couple times, but making french fries with olive oil is a real extravagance.

STONE: I have a recipe in my book for Greek fried eggs. We fry eggs in a lot of olive oil. And I think it’s so brilliant, because you spoon the hot olive oil on the white, and it cooks the egg perfectly. And I got a lot of pushback for that recipe.

SEDARIS: Really?

STONE: People were like, “This is not a recipe.” And I was like, “I understand that, but it is to me.”

SEDARIS: That’s what I liked about your book. It’s just perfect. Here’s a question. Why did you choose to name your restaurant after yourself?

STONE: I’ll tell you that I didn’t name it. My husband did. Because he was like, “I want it to feel like a Greek mom’s restaurant.” It’s a taverna, like the one I just told you in Astoria. It’s just named after the mom, or the dad, or whoever, and it’s like you’re home.

SEDARIS: What’s your strongest food memory?

STONE: My grandma passed away four years ago, but we were really close. And when I would go visit her in Aegina I would rent a car, and she’d get so excited and she would call me her chauffeur. It was a whole thing we did together. And we would go shopping. Because she didn’t drive, it was always a project for her to get to the grocery store. So when I was there, we just went to the grocery stores every morning. And on our way home we would stop at the bakery and we would get a fresh loaf of semi-sourdough bread. And when we would get back home, I would just break off chunks of it and we would put butter and Greek honey on it. I remember that combination being one of the best things in the world. I want to create a butter and honey cake that tastes like that. It’s not too sweet and it’s not too sugary, it’s that amazing combination of somewhat melted butter and the Greek honey that has a very specific flavor to it. How about you?

SEDARIS: Mine’s more like, “Oh, I liked having fish every Friday night. I liked having a roast every Sunday.” I was really into menu planning when I was little. We had this newspaper and there was a little paper within the paper called the “Mini Page” for kids and it would have all the school lunches. A fantasy of mine is just to have a little hole-in-the-wall, a refrigerator with some drinks and Greek pastries. There was an old grocery store near me. It’s no longer there. But I like that at 6:00, 7:00 at night, there’d be a bunch of men in line at the steam table getting dinners for one.

STONE: It’s very utilitarian, that model. A restaurant for single men. I think I would find myself there. I’m feeling so tired of cooking, weirdly, unless it’s at work. In my own home, I’ve stopped cooking.

SEDARIS: Oh, really? Who’s cooking?

STONE: My husband’s an incredible cook, and also Greek.

SEDARIS: Great.

STONE: I think cooking for fewer people is more stressful than cooking for more people.

SEDARIS: That makes sense.

STONE: Because the cleanup is almost the same. You’re using the same pots and pans.

SEDARIS: What do you put in your Greek salad?

STONE: I make it pretty traditional. I don’t put lettuce, but I do like that version too. I like every variation of a Greek salad. But when I make it at my house, I make it with tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, onions, feta, and then I like putting olives and capers in there.

SEDARIS: I could go for a Greek salad right now.

STONE: Sometimes I forget about the Greek salad, and then I make it.

SEDARIS: Especially when tomatoes are in-season. Nothing’s better than August Greek salad.

STONE: The best.

SEDARIS: With some good bread.

SEDARIS: You know, I always judge a Greek cookbook by their avgolemono soup.

STONE: Funny you bring this up, I realized just recently that I do have some thoughts on it. Wait, what are yours?

SEDARIS: On Christmas Eve we have avgolemono soup and this year my brother’s boyfriend made it. I haven’t made it in a while. I just see who puts flour in it or corn starch in it, how many eggs they use, if they use orzo or if they’re just calling it rice. I’ve seen avgolemono soup a pinkish color.

STONE: Yeah, that’s strange.

SEDARIS: Which I’m not used to. My mom made it so well.

STONE: I’m making it right now. I just turned it on.

SEDARIS: You are? Oh, look at you cutting to a pot. Well, let’s hear your thoughts on avgolemono soup.

STONE: It’s funny. My grandmother and her sisters, she had four sisters, they would judge everybody by how many eggs they used in anything. They would always try to find ways to leave eggs out. I never put flour or corn starch in it. I don’t like it when it’s thick like that. I like it brothy, and I like potatoes in it instead of rice.

SEDARIS: Oh, interesting. We roast the chicken. We don’t put it in the soup, and we use orzo, I want to say three eggs, and chicken broth. My brother’s boyfriend can whip the egg whites, but I use a mixer. That’s how I get it frothy.

STONE: I’ve never tried that. Does it add a lovely consistency to the broth?

SEDARIS: Yeah, but it’s still brothy. It’s not super thick. Unless maybe two days later you can see it thicken up, especially with the orzo in there. And then we serve the chicken on the side, where you can put it in the soup. Oh, that’s a perfect thing to make today.

SEDARIS: That’s funny about the eggs. How many eggs do you use in your spanakopita? True confessions. Come on, Mina.

STONE: I use two.

SEDARIS: Wow.

STONE: How many eggs do you use?

SEDARIS: I use a lot. Five is my guess.

STONE: That’s great. I bet it keeps it together and makes it fluffy.

SEDARIS: Yeah. And then last time I made it, I added some ricotta cheese.

STONE: I just learned something from you, which is that I have a deeply-seated hangup with eggs from my family that does not belong to myself at all. And I should just use more eggs.

SEDARIS: See? I’m here to help.

STONE: I got lazy about it. I was like, “Well, whip one into the soup.”

SEDARIS: Greeks aren’t so easy to give up a recipe. They leave something major out of it.

STONE: I thought of you, because one of my good friends collected all of her family recipes, and she photocopied them and put them into this spiral-bound book. She gave a copy to me, and it felt like a huge honor for exactly what you’re describing. Because I’m like, “Is that really what the recipe is, or are you leaving out half of the instructions?”

SEDARIS: Well, it’s your thing. It’s also like teaching Adam how to make spanakopita. It’s great, but that’s also my little party trick. You have a wine [at Mina’s] too, right?

STONE: Oh, yes, I gave you some of that wine. It’s just from a vineyard we really like, and we imported X number of bottles. And we can put our own label on it, which my husband designed.

SEDARIS: That’s fun.

STONE: Greek natural wine, which is just standard in Greece in big plastic bottles, was not readily available here. But now, I think it’s having its day in the sun.

SEDARIS: I agree.

STONE: I mean, the Greeks have been making it since the beginning of time. And they have all these cool techniques that I’m just learning about. It’s really interesting. I want to go on a whole wine tour of Greece.

SEDARIS: That sounds fun. So, are you working on another cookbook right now?

STONE: I thought about it. I started compiling things and I was like, “I am not ready. I’ll know when the time is.” Because as you know, it’s a massive undertaking. I can’t even really believe so many books and cookbooks exist in the world in the first place.

SEDARIS: For me, the hard part was, first, my books aren’t going to teach you how to do everything. I’ll be like, “Take a roasted chicken.” I’m not going to teach you how to roast a chicken. But a lot of it was still describing, like, cutting a potato. It hurt my brain to describe techniques. You just figure it out.

STONE: That is a really hard part of it, because you’re basically doing technical writing for every single thing that you cook, and what’s inherent in your head isn’t to the person reading it.

SEDARIS: Sometimes I think about doing a small Greek cookbook. Just my favorite recipes. But it’s still a big undertaking. [I Like You] was more of a visual book. Photography and sets. It made it a lot harder than it had to be, but that’s the part I liked.

STONE: And it really works.

SEDARIS: Now it’s so filthy. The pages of my cookbooks are stained, and I love that. That’s how I can find the recipe.

STONE: Cookbooks, for me, are journals. They capture a period of time, and I don’t think enough time has passed for me. I would love the “Greatest Hits of Greek Cooking” cookbook.

SEDARIS: Basic, easy, uncomplicated.

STONE: I hope you do make that book.

SEDARIS: We’ll see. I actually want it for myself, just so it’s in one spot.

STONE: Right.

SEDARIS: After my mom died, I took all the recipes, put them together, and made a cover out of construction paper. I stitched a cross on it. Just so everybody had mom’s recipes.

STONE: Oh, that’s so cool, Amy. That’s a real cookbook.

SEDARIS: Are you kidding? Your cookbooks are real cookbooks.

STONE: Just a collection of the food your mother and grandmother cooked for your whole family, that’s so cool. Three generations in a self-binded book.

SEDARIS: Everybody keeps it alive. That’s why I liked going to church on Christmas Eve. Growing up, the service was in Greek, and none of us could speak Greek. So, we could make up our own religion. But visually, we all walked away with the same thing. It was just so beautiful.

STONE: I feel the same way. I’m creating my own traditions too, as time goes on.

SEDARIS: I love that. I should make some Greek meatballs now. If I had a date and they were coming to my house, I liked making them. Because who else was going to make that for you?

STONE: Nobody. That is so impressive. I’ve never been able to do it.

SEDARIS: Oh, really?

STONE: Yeah. I need to try again. I would do them with my grandma and I would just fail. Maybe it’s the eggs.

SEDARIS: Back to the eggs. I love that that’s what you’ve learned from this conversation, your issue with eggs. You’ve got to get past that, Mina.

STONE: Yeah, I know. [Laughs] This has really just been a therapy session in the end.

SEDARIS: Next time you do go to Greece, I’ll beg you to bring back some of that good dye for Greek Easter eggs. Because I’ll buy it at the International Foods on 9th Avenue, but they don’t get the stuff they used to get. I’ve got a couple packets stashed, but I want that blood-red dye.

STONE: I will happily get that for you.