Mona Awad, Author of “Bunny,” Is Kind of Terrified of Bunnies

The bunny is perhaps the singular most versatile mammalian image in modern culture: one of innocence, one of sex, one of lateness, one of sheer horror. In Mona Awad’s new novel, Bunny (out today from Penguin) the figure embodies all of that, blown up—literally—and melded into male fantasy. The novel is set at a fictional, idyllic college campus in New England among a particular group of well-coiffed MFA writing students who nibble on mini cupcakes and call one another “Bunny.” Following the cardinal logic of a teen movie à la Heathers, a cynical outsider, Samantha, is drawn by magnetic force to the allure of the Bunnies, gradually ensorcelled by their “creative workshops,” in which they transform real, live bunnies into real, live men—complete with brooding, blue-eyed gazes and Proust.

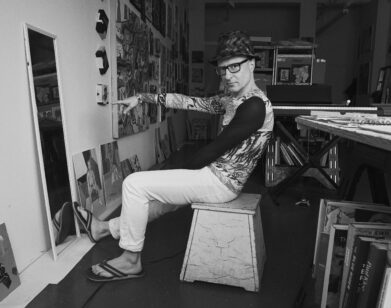

“The Bunnies are so hyper-feminine,” Awad tells me over an appropriately quaint miniature cortado. “There’s always been to me something kind of horrific about that. It’s a monster that I’ll never be able to resist.” The Boston-based author, who also wrote 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, plays delicately with feminine cliches and the oft-hollow pretenses of the graduate collegiate world. Her incisive humor and razor-sharp writing, punctuated with references to postmodern literary theory and the whole range of the emoji keyboard, melds the current with the surreal, the twee with the violent. It’s no wonder the book has already been optioned by AMC to become a TV series. Below, Awad and I dissect the bunny, in all its varied symbolism, and the persistent cultural fascination with the female clique. (And Tim Riggins).

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: The Bunnies are obviously the central force of the novel. What are the roots and cultural influences behind them as a collective unit?

MONA AWAD: Definitely Heathers, and all those teen movies that cultivate that sort of insider/outsider dynamic. Like The Craft, where there’s an insider clique of witches. And Mean Girls, of course. I was doing an MFA, and then I went on to do a Ph.D in Creative Writing. It just seemed like there was a lot in that world that had the potential for horror. I always thought that I would write a great horror novel, just kind of blowing some of the stuff that is part of MFA culture. Samantha [the protagonist] is pretty fucked up. She is kind of like the classic outsider, but she’s lonely and that makes her very susceptible prey to the Bunnies. So, she becomes an insider halfway through the book, and then she experiences that shift, which really changes her.

NECHAMKIN: That’s a classic paradigm of teen clique movies—you have Winona Ryder in Heathers, Lindsay Lohan in Mean Girls…

AWAD: It’s kind of like grad school meets teen movie, or grad school as teen movie. Even though it is a very adult world, there are so many elements of it that feel like high school. It’s so insular. You have your own language. You’re kind of being taken care of, especially if you go to a program that’s paid for. It’s like this separate kind of cloistered existence, and you’re kind of forced into intimacy with each other pretty quickly.

NECHAMKIN: The Bunnies are coded so specifically. They’re extremely intellectual and pretentious but also sort of infantile, even preppy. Was there anyone you had met that you lifted those characters from?

AWAD: I think that combination is very common in the graduate world, at least in the MFA world. It’s kind of funny to observe. The town in which it takes place is kind of like Providence, but not Providence. And Providence has these monstrous undercurrents to it and has a really interesting literary history.

NECHAMKIN: Groups of friends, particularly groups of women, have become such a source of fascination in the culture. Do you think there’s something specific about our conception of female groups in particular that lends itself to drama or even horror? What happens when women come together?

AWAD: The dynamic between women can be so layered. There’s the potential for great connection, but there’s also a lot of potential for alienation. I think especially, too, with the concept of the feminine informing them. The Bunnies are so hyper-feminine. They’re so cute. There’s always been to me something kind of horrific about that. It’s a monster that I’ll never be able to resist. You never know where you stand in those dynamics—that’s what’s so scary about a clique, though that might also be what is so exciting about it. Samantha knows where she stands when she’s outside of it, but she doesn’t know where she stands when she’s inside. That’s more disorienting—and frightening.

NECHAMKIN: There’s definitely a tension there, of being unsure of your own place within the group, always trying to stick to the rules.

AWAD: Yes, that they invented.

NECHAMKIN: On Wednesdays, we wear…

AWAD: Exactly.

NECHAMKIN: Have you been in a clique yourself?

AWAD: I did have a bit of a group in high school, but it felt like we were very much our own individuals. I remember in high school seeing cliques that I was like, “Oh my god, they hurt my ears. Just being near these people, I can’t take it.”

NECHAMKIN: There’s a point during the book in which the girls start literally transforming bunnies into men. Where did that come from?

AWAD: They’re artists, right? So I knew they had to do something magical. I knew they had to make something. Besides teen movies, the other thing that influenced me was the fairy tale. I was thinking a lot about transformation, and about the horror in fairy tales, about desire and fear and how that comes into play when you’re in that environment. So, Beauty and the Beast was kind of where I got the bunny to man thing. There are a million variations of Beauty and the Beast, and there’s actually one called The Hare’s Bride, about a beast groom who’s a rabbit.

NECHAMKIN: Is that where the rabbit motif came from? Or was there a more general fascination with rabbits and bunnies?

AWAD: I’ve always been fascinated by bunnies, because they’re just so culturally loaded, especially for women. It’s something that I’ve heard people call each other.

NECHAMKIN: Really? I’m not sure I’ve ever heard that.

AWAD: Oh yeah, yeah. I heard people call each other that in my MFA program. Actually, I’m just realizing now that my parents called me that, which is really weird to think about. The language of it, that word, was just completely irresistible to me. Because the word bunny, it’s so sweet. But because of all these movies as well, there’s a lot of horror associated with rabbits.

NECHAMKIN: Which movies?

AWAD: There’s that crazy horror movie called Night of the Lepus. It’s about these rabbits that terrorize a town. It’s really scary. Or just think about all those horrific pictures of the Easter Bunny. The Easter Bunny is frightening. It’s a monstrous bunny in a suit. There’s Donnie Darko. When you start thinking about it, they’re everywhere. And then for women, there’s obviously the Playboy Bunnies. The interesting thing about the bunny is that it can assume male characteristics or masculine characteristics, but also feminine characteristics. It’s associated with both genders, both kinds of presentations.

NECHAMKIN: Because ultimately, the bunnies are turning into men.

AWAD: Yeah, and bunnies multiply. Creepily multiply. They’re so cute, but there’s so many of them. It just felt perfect.

NECHAMKIN: And yet, you quite literally blow them up.

AWAD: I know, I know, that was hard. I was kind of like, “Am I really going to do this to a poor bunny?” Apparently yes.

NECHAMKIN: I was looking up bunnies on PetFinder earlier to see if I want to maybe adopt one as a pet. But seeing the white ones with the red eyes in particular…

AWAD: See what I mean? There’s a horrific quality to them. Even Dürer’s “Young Hare”—there’s something very sinister about that rabbit, as beautiful as it is.

NECHAMKIN: If you were to create your own ideal male fantasy out of a bunny, what kind would you create?

AWAD: Tim Riggins. And he’s in the book. The whole thing was a reflection on these women’s own anxieties around romance and where they may get those notions. There’s a chefarpenter bunny. He can’t decide if he wants to be a chef or a carpenter, so he’s a chefarpenter. I was just playing with the desire for cliches, and having those men reflect those cliches back.

NECHAMKIN: You told me the book has already been optioned by AMC to become a TV show. If it were up to you, who would you cast as the characters?

AWAD: Bill Skarsgård as Max because he’s Pennywise and he can do that smile that’s really frightening. Saoirse Ronan, Dakota Fanning, Brie Larson. I feel like Shailene Woodley would do something interesting with Samantha.

NECHAMKIN: The word “borny” comes up a couple times in the book. I’m so curious where that came from. It’s the most amazing term for such a specific feeling.

AWAD: I wrote “bored horny” at first and I thought that was perfect, but I was like, there probably is a borny. I thought maybe I could just invent it. But I looked it up, and sure enough, it’s on Urban Dictionary. I hadn’t heard it, but I guess people are using it. I feel like absolutely a grad student would feel that way. They would be borny, for sure.