Matthew Specktor’s Sense of Agency

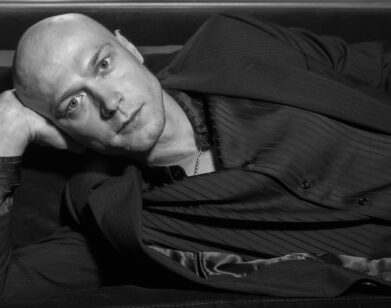

ABOVE: MATTHEW SPECKTOR. IMAGE COURTESY OF JANE PERSKY

In Matthew Specktor’s American Dream Machine, Los Angeles rightfully rises as the pop-culture-colored mammoth that it is—all velvet violet and martini green. Specktor, author of the novels That Summertime Sound and The Sting, knows a thing or two about Hollywood—his father is one of the senior agents at CAA and had the pleasure of guiding Marlon Brando through some of his tumultuous career.

Beau Rosenwald arrives in Los Angeles in 1962. He is overweight, unkempt, and profane, but by the late 1970s, he’s a founding partner at the most successful talent agency in Hollywood: American Dream Machine. We follow Beau and his son Nate, two generations of men, as they move through the luxurious Los Angeles landscape spanning four decades. A sweeping narrative revolving around boys and their fathers, movies and those who make them, and the highs of winning and the lows of loss—American Dream Machine is a story of those who are not always worthy of power.

In a concierge lounge overlooking a snowed-in Boston, we sat down with Matthew Specktor to discuss sadistic storytellers, Mad Men, Raging Bulls, and the complications of dealing in secrets.

JENNIFER SKY: It is quite a tableau that you’ve built in American Dream Machine. The era runs from the martini heavy 1950s to the Guns ‘N Roses ’90s. That has led me to think of it as Mad Men set in Hollywood. Is that something you set out to do?

MATTHEW SPECKTOR: Not exactly. I’d never seen Mad Men at the time I started writing, and all of my models were literary. But I knew the book was going to reflect different periods, that it needed to capture the vapors of old old Hollywood and run well beyond the Raging Bulls era. The ’90s were a time when not just the movie business, but every aspect of American life, became a lot more corporate. There’s a line in Jonathan Franzen’s essay “Perchance to Dream” about how “the rich lateral dramas of local manners have been replaced by a single vertical drama, that of commercial generality.” I wanted to examine that great homogenizing force that came in during the ’90s, since Hollywood seemed a place where it was particularly active.

SKY: Secrecy is one of the themes of this book. The person we see is not necessarily the person they truly are—whether it’s a business-partner relationship or the friendship between three guys, everyone is withholding the truth. Was that something that was complicated to keep a hold of as an author?

SPECKTOR: Sure. But I also think that’s an elemental aspect of fiction. Good fiction necessarily encompasses our limited understandings of one another, and of ourselves. Henry James’ entire career was predicated on that, and I think it’s what fiction is for: to illuminate that gap between our secret selves and our more visible and apparent ones. It was hard in this book because it’s long, and there were a lot of people—a lot of selves, and so a lot of secrets—to keep track of throughout.

SKY: These characters ran Hollywood; they also led larger-than-life lives. We are never without drama pulling us forward. Did you envision them as characters in their own movie?

SPECKTOR: Not really. Much as this book is “about” the motion picture industry, I never thought of it as cinematic. It’s rich in story, there’s a lot of plot in it, which isn’t always something I privilege in my writing. But the central character in this book, Beau, is very large, both literally and figuratively. I knew his life was going to encompass massive gains and unspeakable losses because that seems to be true of people in Hollywood, and of the representative figures in American life. We’re a culture that’s obsessed with people who make and who squander ridiculous amounts of wealth, which seemed an obsession well worth interrogating in a novel. That probably accounts for what some have called the book’s “sweeping” feel, but I don’t know that I set out to be cinematic. I wouldn’t know how to do that in a novel, specifically.

SKY: Yet you were a screenwriter.

SPECKTOR: I was and I am. But I’ve always felt that the basic unit of writing fiction is the sentence, and the basic unit of the screenplay is the scene. I like writing sentences. It’s tactile and exciting. Whereas working at the level of the scene is a more cerebral pleasure. It’s rewarding, but it’s not nearly the same thing.

SKY: You grew up surrounding by the film business. Your father was an agent, your mother was a screenwriter, you’ve worked in production. Was American Dream Machine inspired by true life?

SPECKTOR: In its substance and setting, yes. In its narrative, not so much. My father is indeed a talent agent. He represents actors and directors, but a man less like Beau is difficult to imagine. He’s very urbane and gentle. Still, there’s a lot of real life in this book. Aside from the Hollywood figures who appear as themselves, there’s a tremendous amount of material history. None of the major figures in the book are modeled on any particular people—at all—but the whole thing was shot on location, so to speak. The rooms, playgrounds, clubs, restaurants, office towers. Those places are captured as faithfully as I could manage. I wanted to memorialize a lot of Los Angeles history, for sure.

SKY: It does seem like a love note to Los Angeles. LA is a big character.

SPECKTOR: It’s meant to be. I think that’s good that it carries that quality, it certainly felt that way while I was writing it. I grew up with such mixed feelings about LA, but I do love it, and I feel like the brighter aspects of this place tend to get short shrift in fiction and in film. I grew up lectured by Woody Allen, for example, that LA was absurd, worthy of ridicule and contempt. Most people seem to describe Los Angeles as elementally despicable, or as someplace that requires an apology.

SKY: As somebody who spent 12 years in Los Angeles, I really enjoyed reading about those places. It’s similar to Sex and the City—you romanticized Los Angeles, and I’m not saying you make it better than it is. You make it as is, as I remember.

SPECKTOR: I think that’s how it is. This is an excellent city. People don’t seem to have a problem with a romanticized New York, in fact that’s almost all they ever do, in some sense, is romanticize that place. Los Angeles deserves the same courtesy.

SKY: Nate is our narrator. He has a complicated relationship with his dad. Do you think Nate ever finds the place he truly belongs?

SPECKTOR: That’s a good question, and a personal one. I thought of Nate as an autobiographical stand-in, but also a highly distorted one. He’s no more “me” than his near namesake, Nathan Zuckerman, is Philip Roth. But he partakes of my qualities, and shares quite a few of my own questions. He seems to indicate at the end that he’s arrived at such a place, but I’m not sure I believe him.

SKY: Beau is a great anti-hero. He is sympathetic; at the same time he is deplorable. How did you do that; how did you pull it off?

SPECKTOR: Well, Beau certainly says and does some deeply objectionable things throughout the book. He has some bestial qualities and occasional breakdowns in etiquette, but he’s also extremely honorable. I never thought of him as a monster. I thought of him as a grotesque, and at the same time felt like this could be the essence of his humanity. He’s a little accursed in who he is, but so is anybody. I think we all feel a little burdened by ourselves, no matter who we are. What was important to me was to get a character who had a real range of personality, who could withstand terrible suffering and then turn around and act with great kindness, as well as total insensitivity. Hollywood is famous for breeding monsters, and having worked in the business, I’ve known a lot of them. But only intermittently have I ever found them monstrous. They have many other qualities.

SKY: I recently read A Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford. To me that story is about upper-class society in the early 20th century and how bored they were, so they got into trouble. American Dream Machine is about a different type of upper-class society getting into trouble.

SPECKTOR: I’m glad you had mentioned that. A Good Soldier is one of my favorite novels, for various reasons. But the class question is a good one, because it’s not always easy to empathize with privileged people. Of course we can—I just read Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose books, and those are mesmerizing—but I was very conscious in writing this book that the people in it are insanely privileged. Particularly the younger generation—Nate and Severin and their friends are all young Hollywood wastrels, and so telling their story offered an interesting challenge. I think I’m pretty hard on them. Nate, the narrator, is hard on himself for those things. The characters are hard on each other, they know how privileged they are. The book tries not to be asleep at the switch that way. But also, there’s a fantasy we share in this country—or perhaps it’s just human nature to think so—that success will erase our problems. We seem to believe this no matter how many times we’re advised to the contrary. But it’s never what happens, and it’s certainly not what happens to anyone in this book. This book suggests that success is as large a problem as failure, perhaps larger for the people who are unlucky enough to achieve it. I’ve observed that up close all my life, and it seemed worth thinking about within the system of this novel.

SKY: “American Dream Machine,” that’s a freakin’ name.

SPECKTOR: That name cracks me up. I had it very early in the process, I had it in two pages. I kinda thought, “Oh, it’ll be about this agency, and that’s what the agency will be called.” Then I thought, Jesus, that’s a loud title. It sounded a little silly to me, kind of like a hot-rod magazine or something, but I thought, it’s all right, this book will be a little loud too.

AMERICAN DREAM MACHINE IS OUT NOW. BUY THE BOOK HERE.