Mark Pellington and the Shape of Modern Film

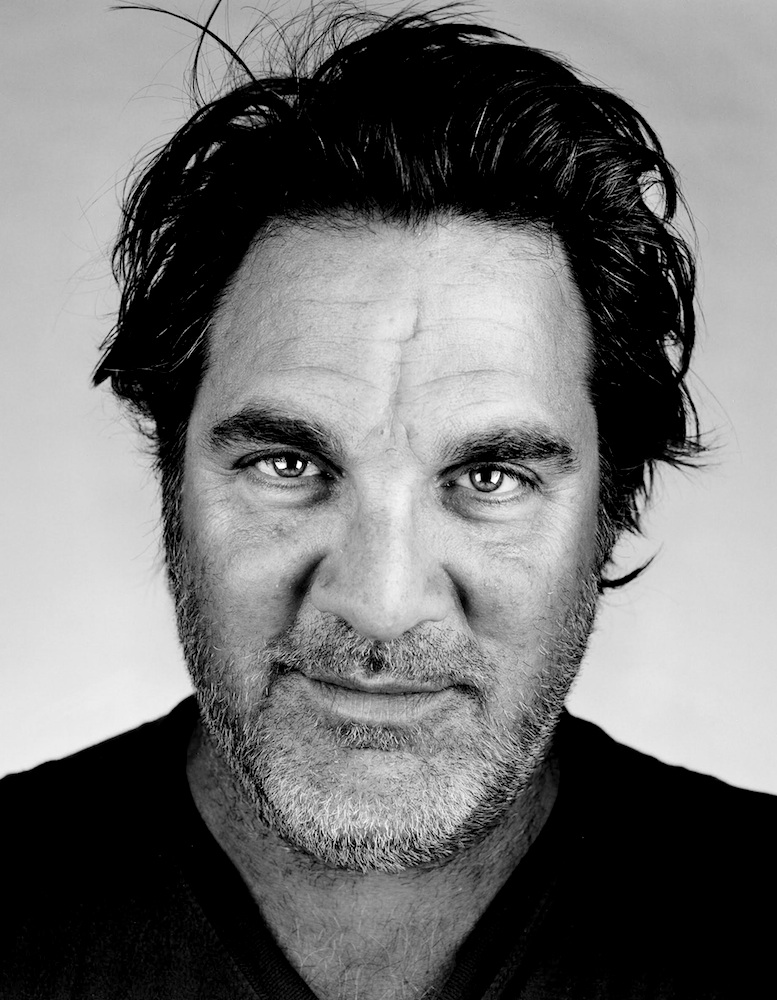

ABOVE: MARK PELLINGTON. PHOTO COURTESY OF MATT SAKATANI ROE.

Raised in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of a professional NFL player, Mark Pellington began as a production assistant at MTV in the mid-’80s. On his days off, he started making music videos for a few of the bands he was friends with. Fast forward five years, and his rapid-cut, collage-like videos such as Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy” and Public Enemy’s “Shut ‘Em Down” were defining the aesthetic of MTV at its most relevant moment. More high profile artists followed: INXS, Bruce Springsteen, Nine Inch Nails, The Flaming Lips, Kings of Leon, Foo Fighters, and, more recently, Kid Rock, Demi Lovato, Michael Jackson, and Linkin Park.

In the ’90s, Pellington expanded into music documentaries and narrative features starring household names like Rachel Weisz (Going All the Way, 1997), Jeff Bridges (Arlington Road, 1999), Richard Geere (The Mothman Prophecies, 2002), Luke Wilson (Henry Poole is Here, 2008), and Rob Lowe (I Melt With You, 2011). Today, Pellington often combines mediums: his most recent project, a short for the New York-based band The Indecent fronted by triplets Emily, Madeline, and Bo Brout out later this month, begins as an extremely personal documentary about the band’s former nanny. Shot in black and white and interspersed with old color footage of the triplets as children, The Hands that Shaped Me begins with calm voiceover memories before transitioning into an angst-y music video. The actor Giovanni Ribisi, whom Pellington met through Jesse Dylan’s production company Wondros, serves as the video’s cinematographer.

Here, Pellington talks to his friend, the filmmaker and playwright Neil LaBute.

The Hands That Shaped Me Trailer from Mark Pellington on Vimeo.

NEIL LABUTE: We might as well begin at the beginning. I met you at Sundance in 1997.

MARK PELLINGTON: Yeah, the nerve-wracking first movie at Sundance [Going All The Way]. You were there [with In the Company of Men]. Vin Diesel was there with his film that he directed Strays. I remember all of us being in this nervous first-timers club. Sundance was really exploding at the point. It wasn’t really the business or media sensation it is now.

LABUTE: Although we were probably hearing that at the time: “Oh, it’s nothing like it was five years ago.” But we were certainly there in that very ’90s explosion of Sundance—how it could power-lift you and your movie to a national exposure. It certainly did for me. I was coming from nothing in terms of making films. My background was entirely theater. You had done all kinds of things in terms of shorter forms. I remember they brought a lot of us together for an article for Premiere Magazine, which now doesn’t even exist. It was all of us in a diner talking with a picture. It was a very mixed group. It always is, I suppose.

PELLINGTON: If you look back at the filmmakers and actors that came out of that, everybody’s navigated their own path. It’s been an interesting journey for me from that first film through present day. I’ve been there four times. The last time, the media had changed so much. The film, I Melt with You (2011) was met with very polarized reactions. It was a very independent, dark [film]. I reached out to you to executive produce, and you turned me on to a great casting director Heidi Levitt, and [it was] very punk rock, running-gun, do-it-yourself. Within three weeks, we got the cast together and said let’s go. Making that singularly changed my life. It taught me to continue to take matters into my own hands. The frustrating part about the film business for me is that you can’t just go make a feature film—I haven’t been able to since I Melt with You. That’s one of the things I wanted to talk to you about, the lower budget features—besides the theater—that you’ve been doing. I think one of the reasons I’ve been making music films and documentaries and music videos is that I just love to keep shooting. What I Melt with You did was freed me up to the idea of continuing to shoot, whether it’s stills or mini-documentaries or poetry films. We have the ability to create. If you wait around for a TV series or a feature film to come together, you could be sitting around for years.

LABUTE: Yeah, we have very different trajectories as you mentioned, and yet we’ve probably learned the same lesson. I am constantly surprised and reassured by the fact that I am still generating a lot of my own work and it’s not waiting for a studio to call or a producer or even my agent. You’ve just got to go make your own fun.

PELLINGTON: I have a film now that I have been working on. An actor I’ve been waiting on for a year just pulled out and said, “You have to wait another year and a half.” This is something I’ve been writing for 20 years, and have actively spent three and a half years financing. I got the money and got final cut; I don’t want to wait a year and a half. It’s not even guaranteed that he will be here in a year and a half. I want to make the movie.

LABUTE: Are you planning to go without that person?

PELLINGTON: I’m going to go get somebody else. There are lots of other guys. To me, the story is more important than the guy. Nobody wanted to touch him and now he is having a little bit of a resurgence. I don’t think that’s the reason—I could never guess the combination of fear, ego, or whatever it is that makes an actor be attached and then pull out. That nature of the business drives me crazy.

LABUTE: I think actors in general have more opportunities placed in front of them. We work with an actor and then we see them a year later when they do ADR and we’re wearing the same clothes. They’re like, “Hey, what have you been doing?” and we are like, “This. I’ve been doing this movie for the whole year,” and they’ve acted in five movies and gone on vacation. So they do get those things thrown in front of them, and they know that their face is going to go on there. Sometimes they hate to be the one that’s raising the money for you. There’s so many things, and so many people whispering in their ears. I understand how they can get caught in the crossfire of “What do I do next?” And as you say, for me, I want to keep working. I don’t want to wait. While this person may be fantastic on screen, I have found—not even the hard way—that that’s the beauty of actors. There is somebody else who can do it, and can do it well. Often after the fact, you go, “Oh, I can’t imagine another person in that part.” But had they not done it, somebody else would have done it, and perhaps done it equally well and certainly differently and in an interesting way.

PELLINGTON: I think what I Melt with You taught me—I remember, I took Steven Soderbergh to lunch and I asked him, “Would you ever put any of your own money into a movie?” And he said, “Absolutely.” And by putting a little bit of my own money into I Melt With You and getting the ball rolling, that’s what gave it the will. He said, “You just have to will it into happening,” and sure enough, that’s what happened. You always think, “I can’t do it for a penny less than X.” [But] too many movies are being made now that shoot for 27 days for under a million dollars that look great. I think if you design it around what resources you can get and you say you’re making it, the actors are more likely to commit when they know it’s real.

LABUTE: Exactly. I’ve been doing that for 20 years. I’ve come full circle from making a movie in the middle of nowhere that no one knew about or cared about, getting exposure through Sundance and going on to the usual suspects of new directors and Cannes and things like that, getting more money and more money, working with a studio, independence, and then virtually back to myself and making movies. Now, I have made a couple of movies that were even shot quicker than the original movie I did. The last two movies have been financed completely independently. We shot in eight days and 14 days. There is so much you can go out and do on your own if you are willing to.

PELLINGTON: When you said, “Okay, we’re going to make it in 14 days,” or, “We’re going to make it in eight days,” you had 100-page script? A 95-page script?

LABUTE: Yeah, or an 80-page script with a lot of dialogue. We were shooting 10 pages a day. That’s a lot for actors to work on and then go off and learn the next 10 so that they can shoot the next day. You’re asking about as much as you can from the actors. But they jump on because they know they’re on this thing only for eight days and the material is different than the things they’ve been offered. And again, they’ll get more opportunities. Yes, they can go off and do three days on something or a supporting part, and make more money in three days than they will ever on something like this, but actors want to be stretched as well and do creative things. They are taking a chance the same way you are. You are taking a chance together.

PELLINGTON: When you were doing that, and you had raised the money, did you call their agents directly or did you reach out to the actors directly? How did you do that stuff?

LABUTE: Both. One person you don’t know, so you have to do that. The other person you do happen to know, so you can email them. It ends up being a mix. Agents hate that you have relationships with [actors] and can call them and have made friends with them, God forbid, because they want to be that conduit. What else are they if they’re not that gatekeeper between you and the talent? So that often can take much more time than just calling up someone you’ve worked with or a friend and saying, “Hey, what do you think about this idea?” But it’s the same thing for when you do shorts, what we should be steering ourselves towards here. When I first did a couple of shorts within the last few years, it was basically for the very reasons you were saying: I want to be out there more. I actually haven’t, all combined, done that much shooting and so I am going to shoot something that I’ll pay for myself and I’ll have that control that I had 15 years ago, which is making anything I want to make. If I want to make it in black and white, I can. If I want to make it in two days, I can. I can ask friends to do it. It can be an off-beat. It can be a direct address, a monologue directly to the camera. No one is going to tell you “no,” because you paid for it. You are now the studio.

PELLINGTON: I went on the tear about two years ago, and I just started shooting. I shot seven music videos in one year and a 57-minute abstract video [Lone] for an artist named Chelsea Wolfe, which is really four videos tied together with a lot of abstract narrative. It’s like a big Tarkovsky movie. We made it for $50,000; shot in four days. It was beautiful.

LABUTE: Now let me stop you right there and ask, something like that, that’s off the beaten path of music videos or commercials or pilots, where does a piece like that go? That’s an oddity even in the world of oddities.

PELLINGTON: It’s on iTunes. It streams on Fandor. But the lesson learned was, I should have made it 70 minutes or made it a feature. She asked me to make a 10-minute music video for one song. I saw her live and I loved the music. I was itching to shoot something and I thought her music was very cinematic. I said, “Why don’t we make something longer?” I wrote a very loose script. As we shot, we edited it to the length it should be. She and her manager were the studio—they paid for it. As we looked at it, it was, “How do we monetize it? How do you get it out there for larger distribution?”

LABUTE: The good news is there are so many formats these days to go to. That certainly helps I think when you create something like that. There are outlets growing and growing that say, “Yes, we are looking for content. We are looking for something different.” With television or even just on the internet. Now the battle is how original can you make that content.

PELLINGTON: Learning about the system of editors on websites is the same as the gatekeepers at studios. The last year and a half has been a real education—trying to educate myself as a creator to open up more opportunities.

LABUTE: Why do The Hands that Shaped Me rather than just a video for The Indecent?

PELLINGTON: In a way, it’s kind of a beautiful payback. When I was 17 years old and living in Baltimore and a little preppy jock, the only thing that made me different from my preppy jock friends was the fact that I was really into punk rock. I would go to the store in Baltimore and buy these imported records and a magazine from New York called Trouser Press, which was the bible of new wave and punk rock music in the late ’70s. One of the writers, who was a kid and probably only three years older than me, named Tim Sommer, turned me on through his writing to all these bands, both American and English, that I never heard of and it changed my life. It literally pointed me towards coming to New York and working for MTV, and that was the pathway towards me becoming a filmmaker.

LABUTE: You don’t shoot as a cinematographer yourself, do you?

PELLINGTON: No, I always work with a DP.

LABUTE: Your visuals are so strong. Were you a still photographer when you were younger? Where did the great eye for images come from?

PELLINGTON: I learned it. I trusted my instincts. I think it took me many years. I look back at some old videos, and I think I developed it over the years from just doing it over and over again. In this space of making and making, Tim Sommer called me. He had worked with MTV briefly. I knew he was a record producer; I knew he had worked for Atlantic [Records]. He called me out of the blue and said he was working with a really interesting, great band out of New York called The Indecent, three triplets. Would I be interested in doing a video? So I said what I say to everybody who calls me and hits me up, “Send me the music.” And they’re like, “Well, we don’t have a lot of money.” And I said, “Don’t worry about it. I’ve made them for $500, $1,000. If there’s a will, there’s a way. If I like the music, sometimes we can piggyback them on the end of the commercials, which I just did for two videos.” You can find all sorts of things. So Tim sends me the music and I really like it and I really gravitated towards this one song. I said, “Can I talk to Emily,” the singer of the band. She explained that the song and a lot of the music is about the loss of their governess, this guy Patrick Lee, who, with their mother and father, really raised them. This guy was a central figure in their life.

LABUTE: And he is in the color footage?

PELLINGTON: He is in that footage. I thought, “I want to do an autopsy of the governess.” That was the idea that popped into my head. I wanted it to be this cold, clinical observation of the events. In the interim, I met, through a friend at our production company Wondros, Giovanni Ribisi. I had met Giovanni as an actor before, but he was shooting, which I thought was really interesting. So I drove over to Atwater Village, and in Giovanni’s compound, he had a full-blown digital tele-correction suite. He had lights. He had this whole production facility and had been producing and shooting. Some of the stuff that he had been shooting, I was blown away by. I showed him some of Chelsea Wolfe, and he was blown away. We were immediately like, “We’ve got to work together.” So I said, “I’ve got this song, we need to shoot something.” And he goes, “Great.” So we were talking about locations and I looked at his place and it had this silver top on the kitchen and white walls, and I said why don’t we just shoot it here. So the band came out.

LABUTE: So that’s his table that the water is running across?

PELLINGTON: That’s his table. I had a list of props. The band had very much their own style.

LABUTE: You mean in terms of the way they dress and all that?

PELLINGTON: Yeah. Maddie and Emily, I think they’re really cool looking. And Emily had this idea of a straight jacket. They are just such engaging, great kids. They came over to my house. We just sat and talked about who they were and Patrick. I had asked them to get some footage for me of him. There was nothing planned. I’ve been making videos in the last couple of years completely intuitively: I get the cast, some props, locations, and I kind of discover it as I shoot it. Some of them are ambitious and some of them are Linkin Park, but I don’t want to know; I don’t want to engineer or plan it. I want it to tell me what it should be as I make it. So with The Indecent, I knew I wanted them to sing and do some performance, because I thought they looked cool. We shot all of them—kind of like a photo shoot. We did moving photo shoots and performances and abstract imagery. As we did it, I said there are two things here: a small documentary music film, and then we could pull in at the end and let the catharsis be the video itself.

LABUTE: Which is the shape of the piece now. But you didn’t feel that, necessarily, until you were shooting? That there might be two things there?

PELLINGTON: I knew when I interviewed them. I felt in the interview with them, they only went to a certain place and they were only comfortable going to a certain place and that told me the limits. I’m a director; I thought, “Maybe this is a longer documentary about this governess, and I’m going to see as I interview them and explore with them what it’s about.” I knew it was about grief, and I personally was very connected to anything to do with grief.

LABUTE: I wanted to ask you about that, how much of that you brought into this knowing their story.

PELLINGTON: My wife died over 10 years ago, and every music video I’ve made in the last 10 years has been, in some way, shape, or form, processing for me. As I interviewed these kids about this guy, they were very protective of each other. I felt that if I really, really pushed them and if I tried to dig deeper on the interview level, something else would have come out. I said let it come out in the music; let it come out in the performance. Let her anger or her frustration—

LABUTE: It’s so imputed in her voice, in her vocal quality. I didn’t know the band before this, but just the way that she sings has so much of that energy in it. It’s really provocative in that way.

PELLINGTON: That was a song from the beginning. [Emily] has many different hats that she wears as a poet, as a writer. She fronts two other bands. I think The Indecent is just one of her outlets for her music. They are all really intelligent, very close-knit. Their mother does a lot of fascinating stuff in neuroscience. They are a really unique tribe.

NEIL LABUTE IS AN AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR, SCREENWRITER, AND PLAYWRIGHT. FOR MORE ON MARK PELLINGTON, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.