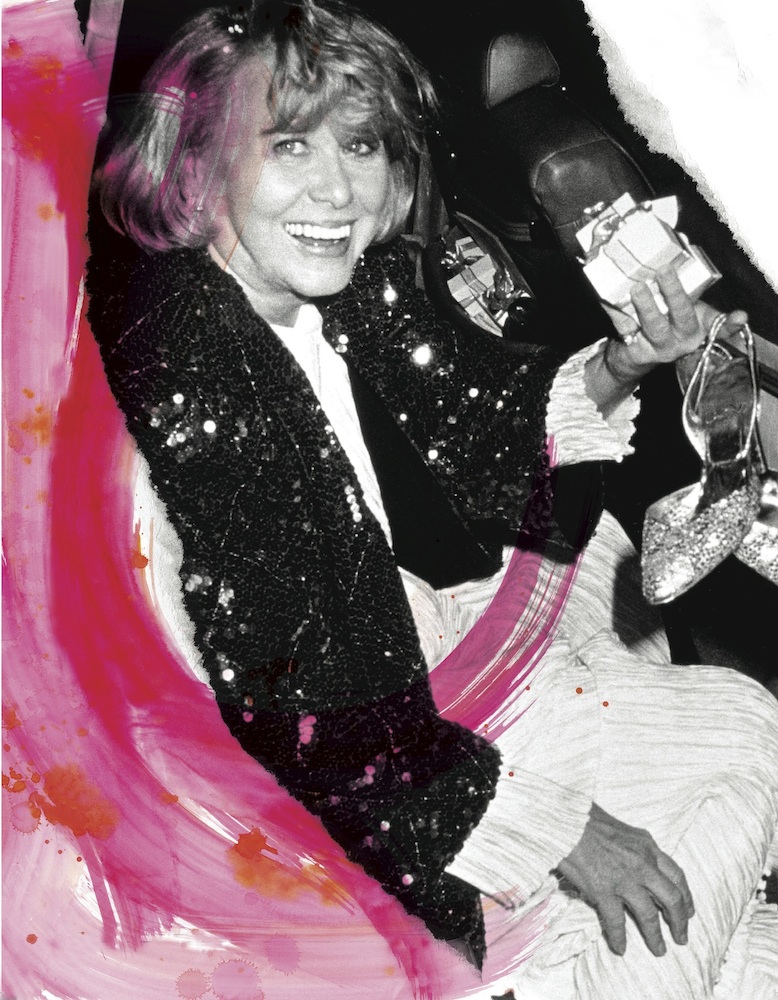

Liz Smith

There are always two classes: the rich and the poor. Celebrity came to the people standing in the street, looking at the king passing by. But America didn’t really have any celebrities. Not true ones . . . And then movie stars started being made. Liz Smith

We tell ourselves stories in order to live, right? But why do we tell ourselves stories about how others live? Why do we gossip, in other words, and why do we love it so? Boy, do we ever love it.

By my supremely unscientific and utterly random estimate, 38 percent of the internet and television is just that—reports on the lives of others, famous others, whether actors, musicians, perfume designers, game-show contestants, or just plain “personalities.” But even before the advent of the dial-up modem, and far before social-media channels turned celebrities into their own best press agents, gossip journalism was a thing that people practiced. It was a trade, and there was no better craftsperson, and none more beloved, than Liz Smith.

At the very height of her career, Smith’s daily column reporting the skinny on the lives of the rich and famous was syndicated in about 60 national papers and read by somewhere between 30 and 50 million people every day. Compare that with The New York Times‘s 57 million unique website visitors monthly for scale. At the time, Smith was estimated to be making a million dollars a year and was herself up there in the firmament with the stars upon whom she was reporting.

Though she now says that she never confused herself for one of them, she was often her subjects’ greatest champion and even protector. When, in the early ’60s, an unnamed woman came forth threatening to sell information that would have outed Smith’s friend Rock Hudson, Smith counter-blackmailed, giving over to Hudson information that would have been damning to the woman. When, shortly after they married in 1964, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, then the most famous people on the planet, would give interviews to no one else, they invited Smith into their inner sanctum for a series of articles, most of them in Cosmopolitan, that made the writer into a star. When Marlon Brando couldn’t figure out how to get his girlfriend Elaine Stritch to sleep with him, he called his pal Smith to ask for help. Hillary Clinton, Diane Sawyer, Mike Wallace, Barbara Walters, and former Texas Governor Ann Richards have been longtime friends. Lee Radziwill and Donald Trump, archenemies.

In acquiring her nickname, “The Grande Dame of Dish,” Smith has, over the course of her 92 years on this earth, played with the best of them, taken shots at the rest of them, and written about them all. As an activist, accidental feminist, and LGBT icon, Smith has, since her film-fanatical childhood in Fort Worth through to her best-selling memoir of 2000, Natural Blonde, and right up to the present, lived a life worthy of her storytelling.

For nearly 20 years, my dad, David Wallace, was Smith’s West Coast correspondent, reporting tidbits he’d scooped up in Los Angeles. So gossip, in my household, is like a currency, and Smith, the World Bank. In early June, I sat down with her at a Tex-Mex restaurant in Murray Hill to borrow a few of the golden tales in her stores.

CHRIS WALLACE: The first cover story I wrote, in 2005, was about Lindsay Lohan. And just as I was going to meet her, my dad called me and said, “Remember, celebrities are not your friends.” Later I thought, “Well, that’s ridiculous advice.” And you, certainly, have not lived your life as if celebrities weren’t your friends.

LIZ SMITH: Well, I wasn’t a very good gossip writer.

WALLACE: There are millions of people who would disagree with you.

SMITH: I have the instincts of a real journalist, so occasionally, if I felt strongly about something, I would kind of go after it. But I’ve made a lot of friends during interviews. In fact, the last time I was in Hollywood, I saw Lindsay Lohan from across the room, and she screamed my name. She said, “You’re the only person who’s never written anything nasty about me.” And I said, “I don’t know anything nasty about you.” I said, “Come over here, you should meet somebody I’m with.” And I took her over and introduced her to Barbara Walters. So the rest was history.

WALLACE: You’ve had these remarkable friendships. And I feel like people are such operators now. There’s a brand of journalist, if that’s what it is, who befriends celebrities as a way of ingratiating themselves …

SMITH: I can’t see how that would work. I would think their sincerity would be ratted out pretty quickly. That’s like being friendly with Annie Leibovitz. She’s going to take the pictures she wants to take, because she’s a bigger star than they are. And she always gets something great. I made friends with Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, and a lot of people. And I thought it was to my advantage. I always had something to write about.

WALLACE: Did you get to know them through work?

SMITH: I went to interview them not long after they were married. And they were making The Sandpiper [1965] in Paris. I took Richard a clipping of an article about Liz comparing the men she’d been with, and he was just blown away by that. When Liz came in, he sort of ordered her, “Sit down, you’re going to like this person.” And I ended up traveling with them all over the world. I had a good time. I used to have a good time.

WALLACE: I think you’re still having a good time.

SMITH: I knew I wasn’t going to win a Pulitzer Prize.

WALLACE: Yet.

SMITH: But I had a lot of real scoops. And they made me some enemies. The Judith Campbell Exner romance with President Kennedy—her abortion—and things like that. Things like David Begelman forging the $10,000 to Cliff Robertson—that Columbia Pictures mess.

WALLACE: That was a time where people had enemies, which seems terribly glamorous to me. I wish I had enemies. Do you have particular stories you think of as triumphs?

SMITH: Taylor and Burton, that was a real triumph. I went to Paris and Rome and New York and Hollywood with them. I went Paris twice. I went to Leningrad, to see her.

WALLACE: You were embedded.

SMITH: And I was with Richard for the last interview he gave. They were divorced. They came here and did Private Lives together. Weren’t married to each other. Whether about work or romance, there was always something to write about them. She was a real star and had been all of her life. He was a frustrated intellectual. He wanted to talk about Dylan Thomas and literature. But he wanted to be bigger than Olivier. So he was frustrated because marrying her just put him in another category.

WALLACE: I wonder if that appealed to him, that you were willing to tell his story.

SMITH: He never complained about anything I wrote. She did, sometimes. One time when I went to meet her, and I hadn’t seen her for about a year—this is the kind of mindset she had—she said, “Liz, why did you write that thing about Mike Nichols and Mia Farrow, meeting in Rome? I asked you not to write that.” I said, “Elizabeth, I don’t remember you asking me. It seemed so harmless.” Which it was. But the fact is she had remembered something she had said to me a year before. I thought that was extraordinary. And she used to always say, “You like Richard better anyway.”

WALLACE: Was there a competitiveness there? Did she feel threatened?

SMITH: Oh never. Not by me. She felt plenty threatened by many other women.

WALLACE: Nowadays we say, “Stars are just like us.” And here’s Elizabeth Taylor, the most titanic movie star in the world, the most beautiful person on the planet, being insecure.

SMITH: They were just like us. If you had everybody jumping at you and taking pictures through your bathroom window, or pictures of your baby, you’d sort of despise the public too. And it’s worse now. The paparazzi has become so aggressive. And the internet has changed everything. There are no exclusives. There are no big stars. Tell me who wrote the Caitlyn Jenner story. The average person starting to read that has never heard about him. They don’t give a shit. They might if my name was on it. Someone would.

WALLACE: How has celebrity changed in your life?

SMITH: There are always two classes: the rich and the poor. Celebrity came to the people standing in the street, looking at the king passing by. But America didn’t really have any celebrities. Not true ones. They had Washington, Jefferson, and Ben Franklin. But that was different. I think [Charles] Lindbergh was the first real American celebrity. And then movie stars started being made. So people wanted to touch and know these people they idolize.

WALLACE: And what is that, wanting to know the lives of others?

SMITH: Well, I think anybody—almost anybody except some intellectual with his head up his ass—would look up to a beautiful woman and a handsome man. I would say it’s looking at your betters. That sounds so snobbish, but that’s what it is. It’s looking at people who are different from you. They don’t lead ordinary lives. But as Elizabeth always said, “First they build you up, and then they tear you down.” She was a little cynical, because she had been a star since she was 10. She died not knowing what it was like not to be her. And she certainly lived a life that people were amazed by.

WALLACE: She was like an Olympian. Am I being overly romantic if I look back at those who came before and hold them in a higher regard—Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, and John Huston are my favorites. Maybe because they were so incredibly quotable, and charismatic. But are they different than the stars now?

SMITH: Well, here’s the thing: In your life, you’ve actually taken a class on this. Because you’ve seen the movies, you’ve read the books. Look what the movies did for literature. Far From the Madding Crowd [1967], Doctor Zhivago [1965] … Celebrity has helped things to last. We think we know a lot about Gauguin because there’s a fabulous movie about him. And van Gogh—I mean, Kirk Douglas. Not to say that it’s accurate, but all biography—which is what films are—gives you an impression. Isn’t your impression of the French Revolution pretty much …?

WALLACE: Based on La Marseillaise [1937]?

SMITH: Yes, and maybe …? I can’t think. The problem with getting old is the names and titles escape you. You may still know how to make an atom bomb, but you can’t remember the assistant’s first name.

WALLACE: What was the first thing that drew you into this sort of mythic world of celebrity?

SMITH: I was always a big movie fan. I was a big Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movie fan. I went to the movies every Saturday with my brothers—with a dime—and stayed all day seeing the movie over and over. So I felt I owned Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. And as silly as that was, you know, working for Mike Wallace was a big transition for me. He loved me from the start and made all kinds of things available. I was meeting Mrs. Roosevelt, escorting her in to be interviewed by him. I observed him when he wasn’t him. And in spite of all of his toughness he laid on, it was an act. Because he was a great journalist and wanted to get the story, he was relentless where that was concerned. But where people were concerned, he was an old softy. And he made a lot of things possible for me. When I got such a good reputation at CBS Radio working for him, NBC hired me. I worked a long time before I got a column. And I only got a column because the New York Daily News was desperate. They had three columnists. They all died within a period of 18 months.

WALLACE: And you’ve had one for nearly 50 years.

SMITH: They gave me a chance, because a lot of people, Rex Reed and others, were telling them that I would be good. I think they took a big chance.

WALLACE: And was this the same time that you’re hanging out with Elaine Stritch and Brando?

SMITH: Well, it’s when I met them. I met Elaine because I knew her agent, and the agent said, “You’re going to Chicago, aren’t you? Look up Elaine Stritch.” And so I called Elaine and said, “I’m a friend of Gloria Safier,” and she said, “Come on, come see my show.” And we just became fast friends. And she was easy to be friends with. And she didn’t ask anything. She thought I was funny. She appreciated a joke. And I thought she was supremely talented.

WALLACE: You guys were real pals. Did you ever feel like you were one of them?

SMITH: No, I never felt like I was one of them. But I knew all about them. I mean, anybody who was in show business knew a hundred stories about Marlon, because the stories were outrageous. But, believe me, having known him, and meeting Irene Selznick, who produced A Streetcar Named Desire on the stage … I’ve met important people because I was just at the right place at the right time.

WALLACE: Did you maintain those relationships? You were friends with, say, Barbara Walters for ages.

SMITH: Well, I met her before she was so famous. She was on a show called Not for Women Only. I guess it was about the same time as the Today show. And Barbara and I became real friends. She would invite me to fabulous parties where I’d be sitting next to Benjamin Netanyahu. And he was Israel’s delegate to the UN. Nobody ever dreamed he would become … Whatever he is. He was young then—young and sexy. And then I began to meet people in government. Through Barbara and Diane Sawyer, too. I used to double-date with Diane and Richard Holbrooke. I used to feel sorry for him. We’d be on a double-date, and these two guys wanted to dance with Diane Sawyer. I was generally left at the table, entertaining one of them.

WALLACE: You, the feminist hero, entertaining.

SMITH: I was such a bad feminist; I was so intent and ambitious myself. I had known Gloria Steinem for a long time. She dated a friend of mine that I’d gone to the University of Texas with. She wasn’t a feminist then. So she becomes a big deal, and she tried to recruit me. And I said, “I’m too busy with my own career to worry about that.” And she said, “Liz, you just want to be the only Jew in the club.” And I fell down laughing. I said, “That’s true.” But then I began to see that she was right, that we didn’t get paid. So I ended up working with her. I saw her just the other night. We were at the Lambda Literary Awards, which is a celebration of LGBTQ writing. Gloria is really an incredible person—more dedicated and real and ethical, a thousand times more than me. I was just egotistical and clawing my way to the top.

WALLACE: Which is the only way.

SMITH: Well, yeah. I didn’t have any money, so it was either make a success or go back to Texas. Or get married again and have some guy take care of me. And I’d already been married.

WALLACE: That’s another thing. Do you get any pressure or satisfaction from being a kind of gay icon?

SMITH: No. I’ve been married twice. I like guys. I like girls. And now I’m so old, this doesn’t come up a lot. So you’re safe.

WALLACE: Shucks.

SMITH: You’re very good looking.

WALLACE: So you’re not in love now?

SMITH: No. You get over being in love. Are you married?

WALLACE: I’m not. No.

SMITH: I probably met you when you were a baby at Thanksgiving dinner.

WALLACE: You did. My dad told me that he would call you every day at four o’clock and give you whatever scoop he’d heard from the West Coast.

SMITH: He was good. He would say things to me like, “This is going to happen.” And then I’d say, “Well, how do you know?” I mean, God, it was dangerous knowing him. Your father certainly has done his part in analyzing Hollywood.

WALLACE: Where do scoops come from now? Is it all personal relationships?

SMITH: No, it’s finished. My kind of journalism is over, done with. Because you don’t believe in it. The New York Post just makes up things, sensational things. They had a picture of Sean Penn, who’s not my favorite person, and Charlize Theron, who’s the hottest thing. She’s so beautiful. And he’s standing off, looking at her. And the whole story is on his jealousy, that she was getting all this attention. They don’t know how he felt! And I doubt that he was jealous.

WALLACE: What does it matter, anyway?

SMITH: I mean, I don’t like him. Sue Mengers introduced me to him, and he turned around and ran out of the building, and didn’t even say, “Glad to meet ya,” or “Go fuck yourself.” But I have to defend him from people psychoanalyzing a picture. And that’s destroyed my faith in it all. People don’t believe what they’re reading anymore. Or they’re idiots if they do. So my kind of journalism is finished. I’m still writing columns five days a week. But I write philosophies, I write about movies. I don’t write gossip. I don’t get any gossip! If somebody like you would give me something, I might think it over, because I believe that you’re kosher.

WALLACE: Celebrities have really taken control of their image management now. If anyone’s gossiping about them, it’s they who are initiating it.

SMITH: Absolutely. And they understand better than anybody what they have to go through. Look at Gwyneth Paltrow, who I don’t particularly like. She was rejected after she won the Oscar because she was high-handed or something. She’s never been popular, really. And she’s made a whole career for herself—selling things, putting her name on things, organizing. She’s got a business. She’s probably a multimillionaire. And you can sell anything now. You know, if you and I decide to pick those flowers out there and say that they were grown in the Kardashians’ garden, we could sell them. For a lot of money.

WALLACE: I think image is the real art form these days. The way people protect and project their own image. Fame is the medium, and images are their art. It’s a whole new frontier. I know you’ve sort of softened on the Kardashians—but who do you think does it really well?

SMITH: Helen Mirren. Absolutely fabulous. Tyne Daly. These women are on Broadway right now, and they are just divine. I was with Helen Mirren having dinner the night before 9/11. And she never forgot that. No, there are plenty of actors, actors who are not important anymore, who call me and say they are coming to this or that. And I say to them, “I’m not important anymore.” Everything has changed. Look how much politics has changed—international relations. Governments rise and fall on speculation.

WALLACE: All of which makes me appreciate how the Caitlyn Jenner story was managed.

SMITH: I have made plenty of fun of the Kardashians, but they’ve been so smart that I’m never going to criticize them again. It’s not important enough. They’d have to rob a bank. Considering the pain these transgendered people are in … I met Kim once, at Michael’s. And she was the most fucking beautiful thing. She was just dazzling. And Bruce Jenner was the sexiest thing I have ever seen. When he won the Olympics. He was really my ideal, my masculine ideal. That’s my one regret.

WALLACE: Was there ever an opportunity there?

SMITH: No, never.

WALLACE: Do you have real regrets, things that keep you up at night, that you wish you’d done otherwise?

SMITH: Oh no. I should’ve given my first marriage a better chance. He was a wonderful guy, and I really loved him. But he wanted to run a ranch in Texas, and I wanted to go to New York and be somebody. We remained friendly until he died. I have regrets that I wasn’t smarter. Mike used to say to me, “You gotta get relentlessly tough.” And then he’d laugh and say, “You just can’t, can you?”

WALLACE: You were too nice?

SMITH: Yeah.

WALLACE: Do you think about things like legacy?

SMITH: Only when I talk to people like you. I still get a lot of trouble. People think I shouldn’t say certain things. Because it isn’t really important, what I’m saying, you know? I went through a period of time when these activist gay men were outing me, saying I should come out. I thought that was unreasonable. I wasn’t going to do that; that would have been the end of my career, at that time. So I just said, “Say whatever you want. Call me a dyke. Call me whatever you want to.” And it passed on.

WALLACE: I think we’ve become slightly better, in that regard. It is widely respected that a person’s sexuality, announcing it, is totally up to them. Not that we don’t continue to speculate. But I do love, just as a spectacular stunt, the fake wedding invitation that the publicist Bobby Zarem sent around as a way to out you and your then girlfriend, Iris Love.

SMITH: Oh yeah. Well, I didn’t really care. It was ridiculous. I just hoped poor Mrs. Love didn’t see it. And she never did, or never said anything about it. I was hoping my mother didn’t get one, but I don’t think they knew where she lived. Phil Donohue called me and said, “Liz, this is the worst thing anyone has ever done. Let’s find out who did this and kill him.” And I said, “I know who did it. Bobby Zarem’s desk is full of these things.” I said, “It’ll pass.” I have been such a failure of my love relationships that they came not to interest people too much. I don’t know how you’re not married. You’re very wonderful looking.

WALLACE: Can I quote you on that?

SMITH: Do you have brothers?

WALLACE: No, I’m an only child.

SMITH: Well, I’m an only child now. And an orphan. I have no living relatives except a few nieces and nephews. And now I just don’t give a shit.

WALLACE: [laughs] Did you used to?

SMITH: Yeah, I worried about what they thought. My father once said something so funny to me. I would send my columns home, mail them, and he said, “Do you know all of this shit? Or are you just trying to get rid of it?” I said, “I know it, and I’ve got to get rid of it.”

WALLACE: Well, they are the same thing.

SMITH: You know, I worked for Interview. I wrote a lot of stories for them when Andy Warhol was still involved, with Bob Colacello. And they never wanted to pay me. Andy would say, “Liz, come up to the studio and pick out a piece of art.” And I never did it. I must have been nuts. But sometimes I wouldn’t get paid at all.

WALLACE: So we owe you money is what you’re saying.

SMITH: Yeah. [both laugh] I don’t know how to explain Andy. He was just an observer. He didn’t participate in anything. And when you would be with him at dinner, he wouldn’t really make small talk. He would say, “Great, great. That’s great.” I finally just gave up. He was not active, and he just wanted to know everybody and take pictures of them. He wanted to be invited. Bob was more normal.

WALLACE: I was thinking about Bob’s book about Andy just now when you were talking about Elizabeth Taylor. There’s the great bit in the book where they go visit her in Rome. She seemed to be both intensely aware of her world and in another world entirely.

SMITH: But you know, after she married Richard, her real job became keeping him from sleeping with other women. She really hurt her career because she wouldn’t come back to the United States and wheel and deal and do business and get properties. So she stayed in Europe and made a series of really not very good movies. And then she finally redeemed herself because Mike Nichols talked her into Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? [1966].

WALLACE: Was that the same era that you were hanging out with them? The Cleopatra [1963] era?

SMITH: I didn’t meet them until a year after Cleopatra, when they married. They had just been married.

WALLACE: Oh right, they had been seeing each other in secret on set.

SMITH: And they had a press agent. A benign press agent and nice guy named John Springer. And he kept saying to them, “You should give an interview to Liz. She’s a real human being, and you’ll like her.” So when they gave me the first one, it just made my career, even though it was a sort of kiss-ass. Then I went to Rome to interview them. And then, you know, they just picked me up. I was part of their entourage. I made a lot of money from them and got a lot of prestige, and got a lot of credit I didn’t deserve. We remained friends. Even after they divorced, Richard used to come to New York and call me. He was just dying to talk to an intelligent person, and he made the mistake of thinking I was one.

WALLACE: He may be my favorite movie star of all time. I just rewatched The Spy Who Came in From the Cold [1965], and the movie with the greatest cast ever, The Night of the Iguana [1964].

SMITH: Oh, the greatest! That whole experience … I knew Ava Gardner on and off for years. She was fabulous. She never gave in to anything. She’d just hike up her dress and go to the bathroom in the Ritz hotel lobby, as she did, in Madrid in the ‘60s. She was fantastic.

WALLACE: [laughs] Well, there’s that great story about John Ford giving Ava Gardner grief about being married to Frank Sinatra. He said, “What do you see in that 120-pound schmuck Frank Sinatra?” And she said, “Well, there’s ten pounds of Frank and a 110 pounds of cock.”

SMITH: But, you know, she eventually left him. And he pulled himself together and gave himself quite a career.

WALLACE: Yeah, he did pretty well. So did you.

CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW‘S SENIOR EDITOR.