Leslie Odom Jr and the Relevance of 1776

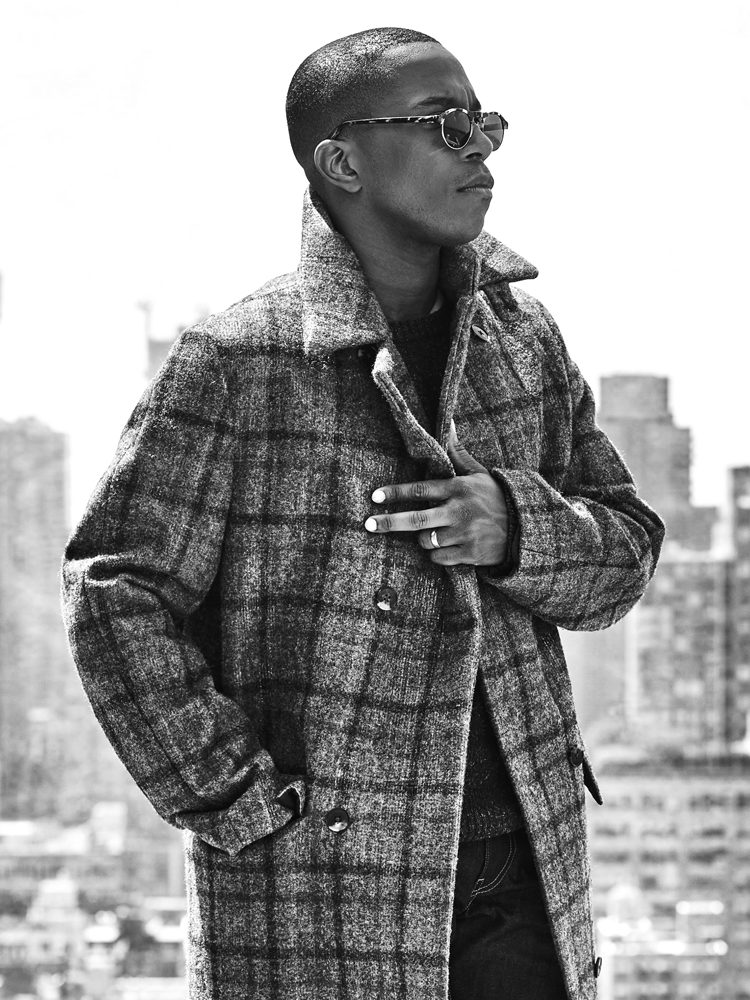

LESLIE ODOM JR. IN NEW YORK, AUGUST 2015. PHOTOS: JAMES RYANG. STYLING: MAC HUELSTER. GROOMING: SCOTT MCMAHAN FOR TOM FORD MEN AT KATE RYAN.

“The only reason to keep talking about history is if you are juxtaposing it with the world that we live in today, if you are learning something about our world by looking at the way they shaped their world,” explains actor and singer Leslie Odom Jr. “That’s what Lin[-Manuel Miranda] has done,” he continues. “He’s making the Founding Fathers hip-hop heads. He’s making the Founding Fathers as hot-headed and sexual and dynamic as Notorious B.I.G., Meek Mill, and Drake… Our show is not about 1776. Our show is about 2015.”

It is a Monday afternoon in Manhattan, and Odom is alert and articulate. Later tonight, the 34-year-old Philadelphia native will resume the role of former Vice President Aaron Burr in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s new musical Hamilton. Yesterday, he was in the recording studio working on the show’s cast album. The day before was a two-show day. There is little time for Odom to relax; after a rave New York Times review (and rave might be an understatement), every performance is packed, with the likes of President Obama, Vice President Biden, Denzel Washington, J.J. Abrams, Meryl Streep, and Dick Cheney sitting in the orchestra.

Told through a mix of hip-hop numbers and classical show tunes, Hamilton follows founding father Alexander Hamilton from his adolescence as an orphan in the Caribbean, through the American Revolution, to his eventual death in a duel. The protagonists are famous dead white men—George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, the Marquis de Lafayette, James Madison—played by a predominantly non-white cast. Aaron Burr is a particularly important character, both the show’s antagonist and, as the narrator, the audience’s closest ally.

Six years in the making, Hamilton premiered earlier this year at The Public before being transferred to the Richard Rogers Theatre on Broadway. In 2009, fresh from the success of In the Heights, Miranda performed Hamilton‘s opening number (Burr’s number) at the White House, and the lyrics are largely unchanged.

EMMA BROWN: Were you always going to play Aaron Burr, or were you considered for another part?

LESLIE ODOM JR.: The first time they asked me to come in they asked me to read Burr. I had seen [a reading of] the show [at Wesleyan], so I knew what it was. I knew what the potential was. It was just a fight because there’s never any guarantee with a reading or workshop. I did probably five or six readings and workshops over two years, and you never know if you are going to be invited back. I just kept letting them know after every time that I loved the project, I loved the part, and that if they were happy with me in the role, I’d love to keep doing it. I didn’t want my intentions to be a secret because when you want something, you’ve got let them know.

BROWN: I heard that you turned down a television role to do Hamilton.

ODOM: When I turned down the TV show, I had a lot of people that were saying, “You should get something in your contract that says you are going to move to Broadway.” I turned down the TV show for the run at The Public. I was just following my instincts, just following my gut. It felt, in a strange way, like I was walking down the aisle with this show, kind of like my wedding. There is no pre-nup; nobody’s hands are tied. I wanted to walk down the aisle the same way that I did on my wedding day, just two people with their eyes open who are making a commitment to continue being in a relationship with each other. This show was so important to Lin and [the director] Tommy [Kail], and it was so important to me, I just wanted us all, every step of the way, to keep checking in with each other: “Is this still cool? Am I still the one you want to commit to? Great, then let’s keep walking forward.” That’s what we did and it feels honest. Nobody was forced into it.

BROWN: What came first, acting or singing? Or were you a musical theater kid?

ODOM: No, I wasn’t a musical theater kid at all. First, it was singing in church—that’s my foundation. When this feels the best, it feels like worship. There is a muse at work; there is an inspiration that is directly connected to church. Then [came] school plays and stuff like that, but I had no awareness of Broadway or musical theater as a job or genre until I was a teenager.

BROWN: Did you study theater in college?

ODOM: I did. I studied at Carnegie Mellon. I went there with a bunch of really, really talented kids. Josh Gad was in my class. Katy Mixon. Griffin Matthews. Josh Groban—he ended up leaving to become a huge star, but he was in our class in freshman year. I remember Josh was this nerdy kid in a turtleneck with a voice from heaven.

BROWN: When did you get your Equity Card?

ODOM: I got my Equity Card with my Broadway debut when I did Rent. I was in high school and I came to New York to do that show.

BROWN: How did you end up in Rent as a 17-year-old?

ODOM: I never intended to do it as a 17-year-old, but they were in Philadelphia on tour and they had an open cattle call, which they advertised on the radio and in the papers. I went to the cattle call thinking that, because I had never done anything like that before, it would take years—and it does for a lot of people. I just assumed that it would take six, seven, eight years, but I knew that’s where I wanted to be. When I was standing on a Broadway stage four months later, nobody was more shocked than me. I couldn’t believe it.

BROWN: Had you graduated?

ODOM: I was a senior in high school. I was a little ahead academically so I could take some time off and I finished school when I got back.

BROWN: Being in the chorus of Rent must be quite grueling.

ODOM: Not at 17. At 17, what’s grueling? My grandmother lived in Jamaica, Queens, which might as well have been Jamaica the island because it was an hour commute from her house to work every day. I didn’t even feel it. On a two-show day, I would go back and forth. I can’t imagine doing that now; I live a 15-minute walk from work now and on two-show days, there is no way I am taking that 15-minute walk. I am taking a nap in between shows. But when I was 17, I would take a bus to the last stop on the E train, and the E all the way to Times Square. It was such a surreal experience. I didn’t feel anything then. The only thing I did feel was I went right from community theater and singing in church to Broadway—there were no in between stops—and so it was a little challenging emotionally because I didn’t understand the professional theater. I didn’t understand the people didn’t go out and bowl every night after the show or hang out at people’s houses—that people had families and they came to work and left. I was the new kid—literally—in town and kind of alone because a lot of those people had been doing the show already. You’re not building a show with these people, and so that was tricky. I totally understand it now but that was the hardest part.

BROWN: Now that you have been doing Hamilton for some time and you’ve got another year to go, do you feel you get something new out of every performance?

ODOM: Well, this show, the reason why I had to do it is because I could sense from my early experiences with it that it was going to make me a better actor and a better person. It makes me a better actor because there are a lot of bad habits that you develop. Hamilton is a masterpiece. Lin doesn’t say that, that’s coming from me. I recognize it as a masterpiece. I have never worked on a masterpiece before. A lot of the material that I’ve done, quite frankly, it’s paid the bills, but it’s subpar material. People are doing the best they can within the constructs of television and how political and sterile that kind of environment can be. There are a lot of tricks you can develop to make that stuff seem better than it is, and none of that stuff works on Hamilton. Those tricks go out the window when you are confronted with a masterpiece. It forces you to develop a more honest, pure way of communicating the material. That’s when you can see what you’re made of as an artist; that’s when you really see what your talent is and what you are capable of.

I recognized that Hamilton was offering me the opportunity to be the kind of artist that I’ve always dreamed of being for the first time. Then I also believe that any sort of emotional or social issues that you have in your life show up in your work and vice-versa, so if you find that you are invulnerable in your work, somewhere in your life, you are invulnerable too. A lot of theater actors, when they come to do TV and film, they come up against that thing of, “My work is too big.” That’s something you should investigate in your life too—are you too big for your room? When you come in, is your presence too big? You can be whoever you want to be, but if you are trying to do TV and film, a lot of times you end up working on those things in your life and so Hamilton, too, was offering the opportunity to work on some things in my work that have affected me in my life.

There is a vulnerability that this role requires that turned out to be quite useful in my relationship and my friendships. There is a presence that this show demands to do it right. We create this show new every single night for that audience. Monday night does not care at all that Saturday night’s show was great. They don’t care that we had a great show for Obama. They care that they heard about it, but they want a great show. So there is a presence required, and I am not just doing that at the Richard Rogers; I am doing that from the time I wakeup, noticing things around me from the time I step out of my apartment and start my day in New York City. In that way, the show is such a blessing to me. In addition to doing wonderful things for my career, it’s making some really tangible and I hope long-lasting changes in my life.

BROWN: When I saw the show, Lin wasn’t playing Hamilton. It was still excellent, but does it change the dynamic to be acting opposite a different person once a week?

ODOM: Absolutely. That goes back to that presence thing. This show shouldn’t be the same when Lin’s not in it. We have played the show so many times with Javi [Javier Muñoz] now; he’s part of the family. It doesn’t feel like we’re up there with a stranger. He’s definitely part of our crew, but one of the also great things of playing something that’s well built—Lin and Tommy and Alex [Lacamoire], our orchestrator, have taken great care to design this thing for the long haul—is that it can withstand a cast change, it can withstand if I am a little sick, if I am a little tired. I know that the piece is still going to reach you in your seat if I don’t hit the high note. It’s not about that. It’s not a piece that’s based on high notes or tricks or the virtuosity of our dancers—the emotional impact is still the same in the show because it’s built for that.

Lin did not want to make a show that worked only when he was in it. That is useless. The show needs to last long after all of these brilliant performers leave. What we brought to the table will always be in the DNA of the show, and I am very thankful for that. That’s what you get to leave behind—a certain level of excellence and a certain level of passion that’s always there. When I got to Rent two or three years after they opened, it was still there. The [original cast members] were all gone but the thing that they left was still there in the dressing rooms, in the wood.

BROWN: Do you feel like it’s still important to talk about the Founding Fathers? Their place in contemporary politics sometimes feels very negative because people use them to hold onto these misinterpreted, archaic ideals.

ODOM: Yes. I think we see time and time again that if you don’t know your history you are doomed to repeat it. My wife is half Jewish and it’s a culture, the same way that being black is cultural. We have Seder every year and we tell these stories—some biblical and some just about the history of their family—because the cultural mantra is to never forget because we can never let this happen again. That is the most beautiful and powerful thing. I love it. It’s my favorite holiday that my family has. You need those reminders. We look at what’s happening in this country with civil rights, and a lot of that is because it was such a painful thing to come out of.

Not to blame them, but my parent’s generation, I feel, wanted to shield us from a lot of that. They just wanted us to succeed; their aspirations were honorable and they were understandable—it was a middle class aspiration. My parents were the first generation to go to college from their family. With their children, it was taken for granted that we’d go to college. We could study anything we wanted, but of course we’d go to college. Handing down stories of that pain and those battles that my grandfather had been through, that my great-grandparents and my great-great-grandparents had been through, they didn’t want us to have a legacy of pain and horror. But I think on some level they did a little bit of disservice to our generation, because people don’t feel a responsibility to the legacy. I don’t think we feel enough responsibility to vote because it’s not ingrained in us what price the right to vote came at. The importance of the history can’t be overstated. I love the quote that says, “A man that doesn’t know his history is doomed to be a child for his whole life.” It’s like not remembering what you had for breakfast today. You get to the end of the day and you just have no memory of what’s happened since you woke up. You can’t learn anything from that.

BROWN: What do you want to do after Hamilton?

ODOM: I don’t know. Great roles are limited for everybody. It’s not just a black thing or white thing, but I can only speak as a black actor and roles like this don’t come along often. I hope that there are roles that come along that are as interesting and as nuanced and as special as this one, but I don’t know. It would be painful to go backwards after this. I love TV—the little bit of money that I made in TV allowed me to work Off-Broadway for six months and not be completely destitute. It’s been good to me, but a lot of times when I work on TV there’s a whole lot of stuff that I have to leave at the door. There are a whole lot of things that are in my skill set that TV does not require of me. I just hope that I don’t have to take steps backwards to make a living.

HAMILTON IS CURRENTLY ON AT THE RICHARD ROGERS THEATRE. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE PLAY’S WEBSITE.