Larry Kramer Is Still the Angriest Gay Man in the World

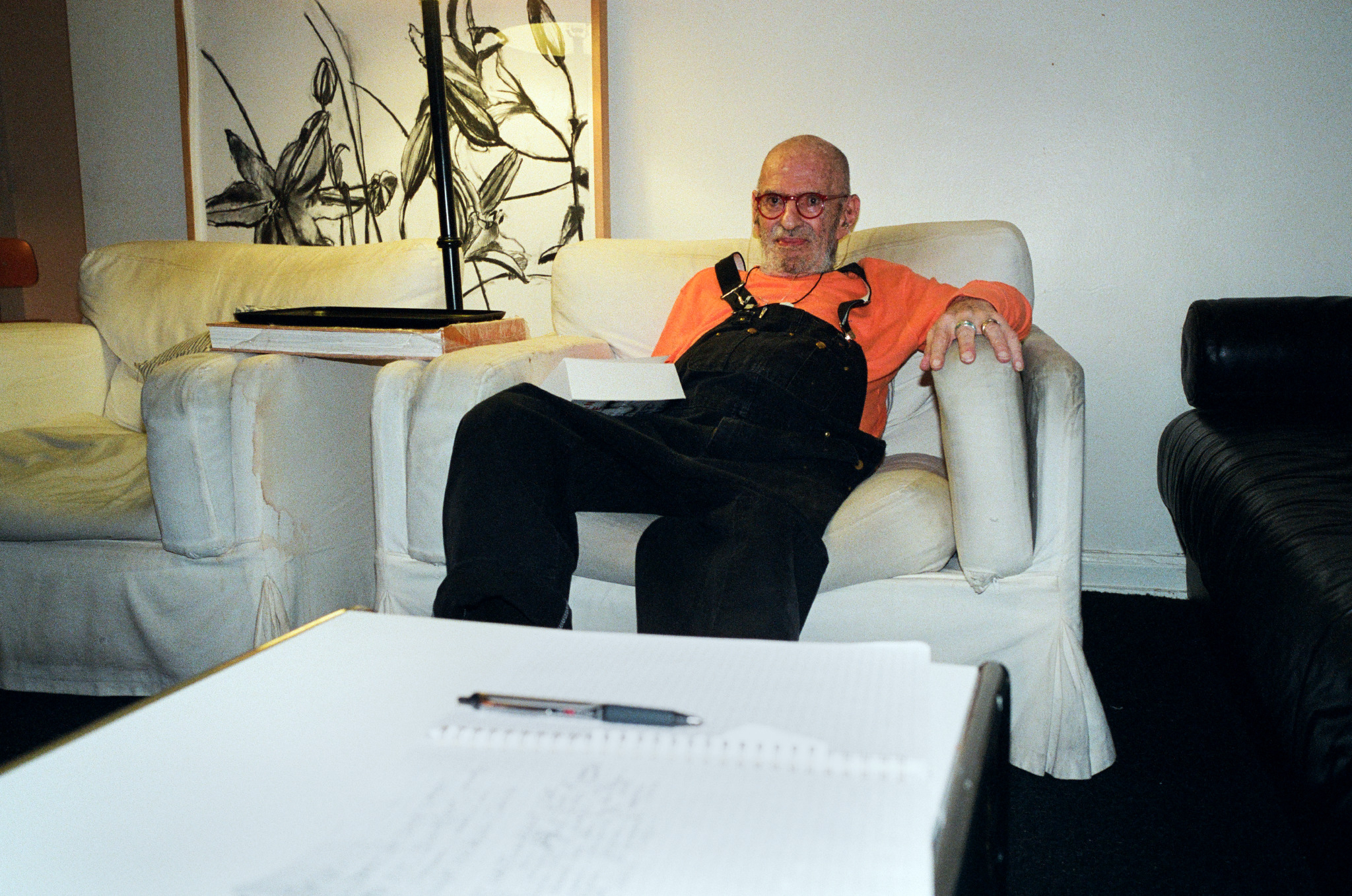

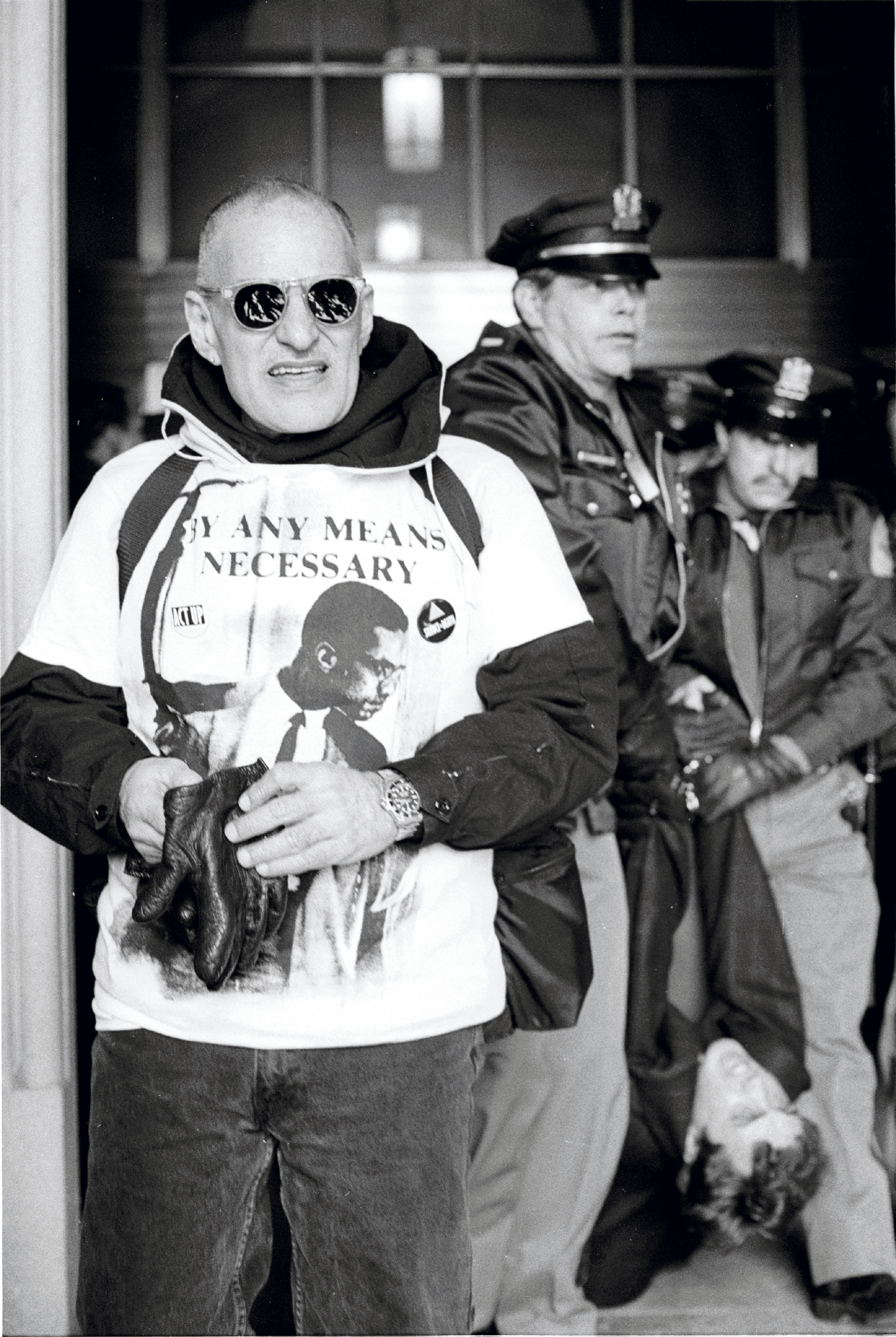

“Nobody lives,” we’re told toward the conclusion of The American People, Volume 2: The Brutality of Fact. “In the end that is the short and simple. Nobody lives. Talbott is sick. Norman is sick. Cal is sick. Hobart is sick. Mark B. is sick. Randolph is sick. Manolo is sick. Frank is sick. Robert G. is sick. Ted is sick. Myron is sick. Alfred is sick. There are more, overwhelmingly more. I can’t recall all their names. My memory is sick.” No writer has been able to chronicle the horrible, maddening, delirious depths of the AIDS epidemic in America like the 84-year-old activist, writer, and gay icon Larry Kramer. For him, it is not his memory that is sick, but the country itself—particularly its conscience. The longtime New Yorker has spent most of his life standing up, shouting from the top of his lungs, blocking doors, and naming names for the purpose of saving lives. After clocking time as a burgeoning Hollywood screenwriter in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Kramer returned to Manhattan, and so began one of the most radical, trailblazing careers in American letters. In 1978, he wrote the controversial gay-life novel Faggots, incendiary for its frankness even among its own community. When AIDS began to devastate that very community in the early 1980s, largely due to the cruel indifference of the culture at large, Kramer penned a play, his third, that soared and raged and howled about the suffering and losses of this new disease while the politicians looked away and the medical experts wringed their hands. The Normal Heart is a bellwether work in its power of art and provocation. By the time it came out, Kramer had already co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis and, in 1987, he took his anger and defiance to the streets with the formation of ACT UP. The heroism of that movement, with its strategies for civil disobedience, has not been matched to this day.

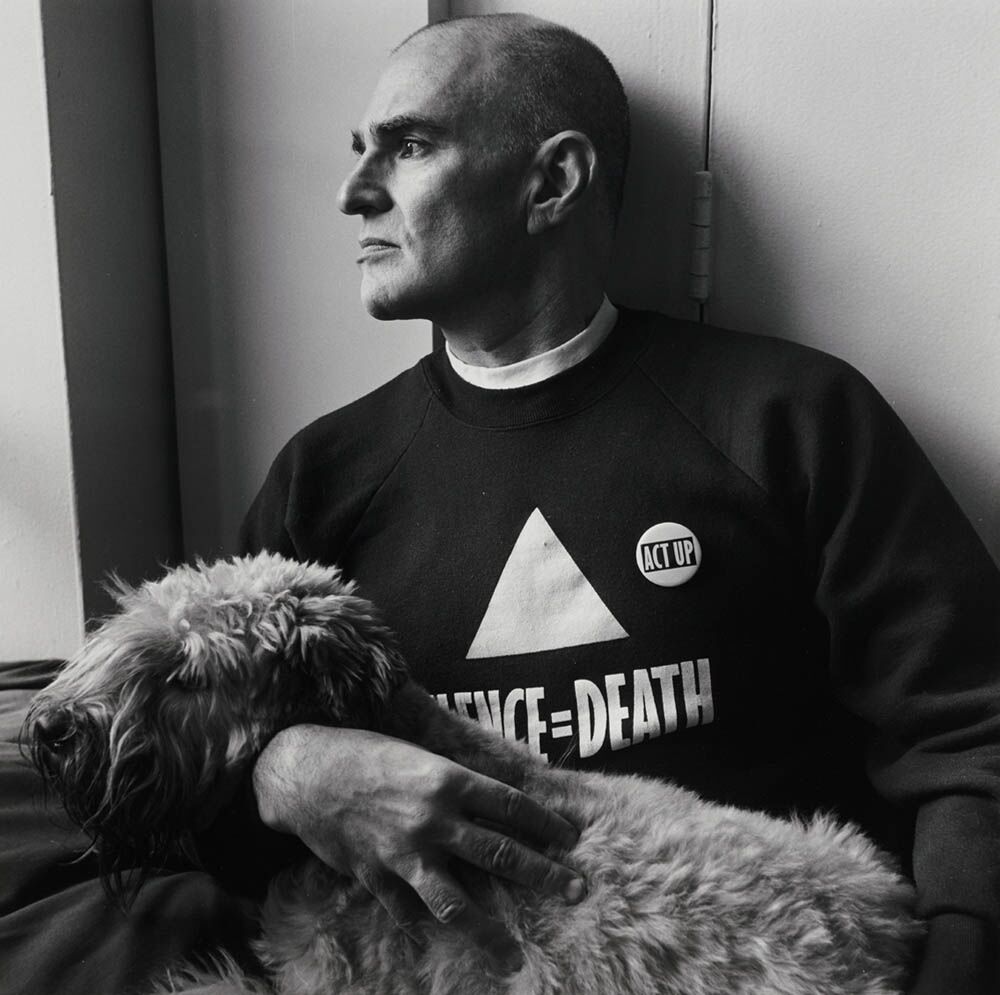

When Kramer finds an enemy, good luck to that person. His battles have been legendary, his willingness to engage profound. And he’s not done yet. This January, Kramer is publishing The Brutality of Fact, the second volume of his novelistic meta-work The American People, in which the author has taken it upon himself to amend American history from its delusional straight domain with the willful insertion of high-spirited gayness. The first volume, published in 2015, finds the founding father (and, according to Kramer, the homosexual war hero) George Washington gracing its cover. This one bears the face of Kramer himself. It picks up the plot in “postwar America,” although, we quickly realize, we have never been without war. One still rages on.

The actor Ellen Barkin first met Kramer in 1995 when they both appeared on a talk show. Barkin went on to star in the 2011 Broadway revival of The Normal Heart, for which she won a Tony Award, and the two have been good friends ever since. Late last October, Barkin stopped by Kramer’s apartment off Washington Square Park to talk to the famously angry activist about fights both old and new. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

ELLEN BARKIN: Since I did your play in 2011, my life has changed, my world has changed, and my response to the world had changed. That’s because of you. I re-watched the documentary Larry Kramer in Love and Anger [2015] last night and when George C. Wolfe says something like, “One person said no, and then another, and that’s how you make change, and that’s how you start a revolution,” I thought, that’s the lesson of Larry Kramer to me. It’s one person making a difference. That’s you, fighting, and out of that came a revolution and the salvation of hundreds of millions of lives. You also brought back an art form sadly missing. When I was doing that play, I felt like I’d never do anything more important.

LARRY KRAMER: You were brilliant in the play.

BARKIN: Well, that’s the Larry Kramer effect. So here is my question: There’s a Senegalese filmmaker named Ousmane Sembène who was asked if his anger and his rage got in the way of his art. He paused, looked at the interviewer, and said, “My rage is my art. My rage is my freedom.” Is that true for you?

KRAMER: I don’t know. It just seems to be a part of me. I had a terrible childhood as my father and I fought all the time, so I was used to fighting back.

BARKIN: You were a shy boy. How did you have the strength to fight your bully of a dad?

KRAMER: That’s a very good question. He called me a sissy and it made me mad. I don’t know where anger comes from, but I find it a very positive emotion.

BARKIN: As do I.

KRAMER: People pay more attention to you. That’s the lesson I learned early on with Gay Men’s Health Crisis—you get paid more attention if you’re loud and obnoxious. Otherwise, you’re just another person. I slowly started getting more and more angry and came to be known as the angriest gay man in the world.

BARKIN: But you were angry before. You were angry when you wrote Faggots. You were angry when you wrote The Normal Heart. I identify with that anger. I didn’t have to reach deeply for my character’s righteous indignation and sense of injustice. It’s in everything you write and every move you make. So what now, Larry? Look where we are now.

KRAMER: There are different opinions about where we are in terms of AIDS. It’s still awful, in terms of the gay world. So I’ve written another play to go with the last Ned Weeks play [The Normal Heart], in which Ned feels that he’s failed.

BARKIN: And I know you feel that, even though you should understand the enormity of your success. You did save the lives of millions of people. But, yes, millions of people are still dying. I was reading a piece where Kevin Sessums wrote that being gay is a sacred part of who Larry Kramer is.

KRAMER: I love being gay, and I love gay people. I think we’re better in positive ways. I think we’re more talented as a population. I think we’re better friends with each other. I think we’re just a very special people and I see that we’re wasted as a people partly because of our own fault of not fighting back.

BARKIN: What should the 30- to 40-year-old gay communities be doing?

KRAMER: We were doing it quite well for a while. I started ACT UP, which was probably one of the most successful grassroots organizations that ever came into existence. All these drugs that are out there are really out there because of what we did, our small army of very frightened, angry men, mostly young, who were terrified of death and who were anxious to fight back and think of ways to get the message out. We forced those drug companies to listen. And now those drugs cost a fortune. Most people can’t afford them, so we’re back to the mess again. People are still getting infected. People can’t afford the drugs if they don’t have some kind of insurance, and so, in a way, everything we fought for has been—

BARKIN: Don’t say it’s all for naught.

KRAMER: It’s not for naught, but it’s not what we’re capable of doing. We’re wonderful people. Realize it. Be proud. Be supportive. Love each other and fight for each other. But we’re not good fighters. The gay population doesn’t have any political power.

BARKIN: But now I have an argument to pick with you. Why is the gay male community not standing up more for the #MeToo movement?

KRAMER: The one thing I’ve never been able to answer to my satisfaction is why, at the height of the AIDS horrors in the mid ’90s, every gay man in America was not out there fighting along with the few thousand who were in ACT UP. Why? I couldn’t understand why people weren’t willing to fight to save their own lives? I don’t know why, and that’s what breaks my heart.

BARKIN: It looks to me the fight now is coming from the trans community.

KRAMER: Yeah. But they’re not getting enough support from the non-trans communities.

BARKIN: Did you read the paper today? Somebody at a Trump rally was screaming about “the fag mayor” who is running for president. It’s like it’s happening all over again.

KRAMER: That’s why I’m depressed and blue. It’s happening again. People are still dying. And we don’t have any gay leaders. We don’t have a Gloria Steinem or a Bella Abzug.

Courtesy of Larry Kramer.

BARKIN: Why doesn’t the women’s movement of today have a central figure either? There were dozens of them when I was 15. Nobody has filled that gap. I remember you and I first met when we both happened to be on Charlie Rose. I was so anxious because you were there riling everybody up and I was like, “Oh, now I have to go on, just some idiot actress.” [Laughs] But what you were doing—that was back when you were outing people—was such a revolutionary act and people were scared shitless. Why aren’t we doing that now?

KRAMER: [The theorist] Hannah Arendt has been very influential to me. She was angry at the Jews, even during the war, and thought that they should have their own army to fight back. I was saying that about gays. I looked at ACT UP as an army. Unfortunately, a lot of ACT UP didn’t like the comparison with an army, but we did a lot of those types of things, like Operation Wall Street. But I remember saying to the spokesman, “You don’t have any goals. You just say, Wall Street is terrible. And that’s not enough. You’ve got to fight for something specific.”

BARKIN: That’s what’s happening now, I think. Everybody’s just walking around saying, “We want to be treated better.” It’s not enough. We have to narrow the focus.

KRAMER: Well, you’ve got to do something that you care about personally, passionately, and all my friends were dying. That was good enough. But the minute we got pills, activism stopped. ACT UP self-destructed. They make all these movies about the successes of ACT UP, and it’s not a happy ending because you get the drugs, but that’s not the ending. The ending is everyone turning on each other. People got the drugs and went back to the lives they live, and that’s what got them in trouble in the first place. And, that’s where we are now, I think. Everybody thinks AIDS is all gone as an issue. But we still don’t have a cure.

BARKIN: And the drugs that are out there cost so much money.

KRAMER: You know, the first AIDS drugs are based on research that was funded in the ’60s at the National Institutes of Health under a research grant. And the NIH went into partnership with one big drug company under the belief that it would get the drug out there faster than anyone else. So, in essence, we, the taxpayer, paid for all of that research because we had financed the original doctor’s research. To this day, all these drugs are based on stuff that taxpayers in part have financed.

BARKIN: But we don’t have access to any of it, and it’s $3,000 a pill. Larry, if there were never AIDS, where do you think your activism would have found its home? Or would you have been Larry Kramer, novelist and playwright? I know you didn’t like writing screenplays.

KRAMER: I hated writing screenplays, but I happened to be very good at it. I actually wanted to be—you’re going to laugh—a comedy writer. I wrote a play called Just Say No, which is a farce. It was about the Reagans. It was panned by the New York Times.

BARKIN: So where do you think your art would have gone?

Courtesy of Larry Kramer.

KRAMER: Who knows. I didn’t like writing screenplays, but I had an Oscar nomination. I lived in England all those years. When I came home I decided I wanted to write plays. My first play was called Sissies’ Scrapbook [1973]. It was done at the first Playwrights Horizons, which was, in those days, in a gymnasium in the YWCA. The only reason I was able to live was because my brother had invested the money I made writing a movie called Lost Horizon [1973]. It was terrible but I was paid a fortune.

BARKIN: Look, it allowed you to get down to business.

KRAMER: That’s right. And what was the next move? It was AIDS.

BARKIN: There wasn’t a single movie project from your Hollywood days you liked?

KRAMER: I brought Women in Love [1969] to the producer. That was mine. Making Women in Love was not easy, because it had difficult people in it. It had Glenda Jackson and Oliver Reed and Ken Russell.

BARKIN: Ken Russell was the craziest of the crazies.

KRAMER: Yeah, but the film was well received.

BARKIN: It has the greatest homoerotic scene ever, the nude wrestling scene.

KRAMER: I had to fight for that. In London in that time there was a censor.

BARKIN: I don’t know how you got away with that.

KRAMER: I’ll tell you how. The dialogue of that entire scene is word for word from the [D.H. Lawrence] book. I brought the book and said, “Isn’t it stupid to censor it in a movie when the book has been in print since 1920?” John Trevelyan [the censor] gave in.

BARKIN: I remember when I saw first saw that, it was shocking. Oliver Reed spent his whole life talking about what a big dick he had. So when I watched it again, I realized, “Oh, that’s why he was always facing the camera!” He was proud of his prodigious penis.

KRAMER: You want to know why Oliver Reed’s penis looks big on the screen?

BARKIN: Yes, it was a little tumescent. You could tell.

KRAMER: He was afraid that Al [Alan Bates] was bigger, which he was.

BARKIN: I feel sorry for men. It’s very sad.

KRAMER: Oliver Reed was a very strange man. You didn’t know whether he was going to show up with his wife or his mistress. And he was overweight when he was cast, and he was only cast because United Artists had a big movie with him in it, and they would let me use Glenda if I used Oliver, because I wanted Glenda and nobody wanted Glenda in that. She was the stage actress from the Shakespeare Company. She had terrible hair. She had terrible teeth. She had varicose veins that you could hang things on. And we wanted her!

BARKIN: But she was brilliant.

KRAMER: And yet, Ken didn’t want her because he’s such a visual director. His wife was the costumer and Glenda was very hard to dress. In addition, she got pregnant during the movie. Oliver, in the meantime, had drunk himself into a state. I said to him a couple of weeks before we filmed the nude wrestling scene, “Oliver, you’re going to appear naked before your millions of fans and you’re too fat.” Every night, all night long, he sat in the sauna to get in decent shape for that scene. That’s what making a movie was.

BARKIN: I always say you can get actors to do anything. But, let’s go back to politics. What would you say to activists today?

KRAMER: We’ve got to be united. We’ve got to learn how to fight together. We also have to take it one day at a time. That’s what I learned in ACT UP because you’d call a reporter and they’d say they knew nothing about AIDS, so you’d teach them AIDS 101 and then they would say, “Call me back.” And when you’d call them back, that person was no longer there, and you had to start all over.

BARKIN: Tell me about the outing phase. I’m fascinated with that approach to activism, especially with what’s going on now with women and the church. Everybody’s saying names. It’s necessary, right?

KRAMER: Right. I certainly called [Mayor Ed] Koch gay in public.

BARKIN: And you certainly made a lot of people angry by your anger. People don’t want you to rock the boat.

KRAMER: And I was a loudmouth. People would walk across the street to not be near me. People would also thank me for what I was doing, and I would say, “For what? Why aren’t you doing it, too?” And they didn’t like that either.

BARKIN: It’s that lack of focus. People feel lost. Women, Jews, gays, people of color—we’re the disposable ones.

KRAMER: Everybody is disposable.

BARKIN: My Bubby would always say, “Maybe it won’t be the Jews next time. Maybe they’ll come for the gays, they’ll come for the blacks.” And she was right.

KRAMER: She was absolutely right.

BARKIN: So, Lar, you’ve written volume two. Is there going to be a volume three?

KRAMER: No, I’m done. There’s nothing more.

BARKIN: What you’re done is written the history of gay people in America, which really hasn’t been done. It isn’t anywhere.

KRAMER: What pissed me off is that play Hamilton on Broadway. There’s no reference to his being gay. And he was. He and George Washington were lovers. I’m still mad that the guy who wrote the Hamilton biography references all these interactions that Hamilton has, which were obviously gay. And the biographer will write something like, “You’d think he would be gay, but he wasn’t.”

BARKIN: There were gay men all along.

KRAMER: Tell me what you think of volume two. It begins more absorbingly than volume one. It starts in J. Edgar Hoover’s male whorehouse.

This article appears in the winter 2019 issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.