‘Dildos in the Sky’: Kate Wagner of McMansion Hell On Our Return to the Tackiest Era of All Time

To converse with Kate Wagner is to incur an explosion of architectural history, tidily wrapped in Marxist thought and neatly tied with the biting strings of Twitter-friendly snark. Though she may not be a household name quite yet, Wagner — a frequent contributor to sites like Curbed and The Baffler — is the brain-force behind McMansion Hell, a blog whose sharp, bite-sized cultural commentary has managed to cut through the cluttered panoply that is the “take economy” of the late internet and earn a cult following in the process. Wagner’s blog, which she launched before earning her Masters in Audio Science at Johns Hopkins, uses photos of McMansions — those oversize gaudy mainstays of American suburbia — to unleash an incisive commentary that roasts their complex rooflines, asymmetrical windows, and excessive columns, organized by the logic of a meme. Interview caught up with Wagner the morning after she delivered a sold-out talk at NYU to discuss our cultural return to early-aughts aesthetics and the politics of tackiness — from farmhouse kitchens to Paris Hilton’s exposed navel to the McMansion-y faux-populism and HardiePlank-thin facade of Donald Trump.

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: Did you grow up in McMansionville?

KATE WAGNER: I grew up in a small town in North Carolina. There were McMansions around in the wealthy parts of the county, and I was always fascinated with them because they were always so massive and strange-looking. They took a normal house and exploded it. They bulldozed the woods next to my house growing up to build a big, ugly house. I had a little bit of spite behind the idea, but I always found them interesting.

NECHAMKIN: And the socio-political implications of them.

WAGNER: The architecture of conspicuous consumption and the isolation. The houses are so far away from pretty much anything. You have to drive fifteen minutes to get a gallon of milk at Walmart. They’re just completely car-dependent most of the time. I always found them to be fascinating portraits of American culture. They kind of embody the isolationist American idea of This is my plot of land, and the power that comes with that. It’s about taking the architecture of the normal suburban house to new expanses: Look at how much suburban house I have, and you don’t. So you have these monumental elements to the architecture. Huge foyers, with huge chandeliers and huge staircases, giant emerald-like kitchens, like they’re on the cooking channel or whatever. You have these spaces for entertaining that just completely isolate different parts of the house from one another that are rarely used, statistically-speaking. It’s aspirational. It’s the dream house built for the parties that you’ll never have. You see all those HGTV shows where it’s all about how to paint your walls so you can sell your house for a thousand more dollars. It’s the consuming of the home as a commodity itself. I think that is a very backwards way of thinking about what architectural space does for us. The act of conspicuous consumption is so divorced from the act of actual dwelling. If people actually designed their homes for living, they would be a lot smaller and cozier. There wouldn’t be farmhouse sinks and gray walls everywhere.

NECHAMKIN: How do you find the worst offenders?

WAGNER: I have a method of searching real-estate websites. It’s gotten a lot harder. You know how, when you’re in the shower and the water is hot, but you have to keep making it hotter because you get adjusted to it? That’s how it is with the ugliness of McMansions. It takes months to find them sometimes. You can’t just do normal ugly anymore. They have to be atrocious.

NECHAMKIN: Is there specific period in time you associate with the McMansion?

WAGNER: As far as the actual evolution of what we call the McMansion, meaning these large suburban houses that are built using contemporary materials, there’s a correlation between liberalizations in mortgage laws and things that were done in the 1970s to stimulate home buying and construction during the oil crisis. These changes essentially enabled people to borrow more money at varying interest rates. There was a lot of financial deregulation that had happened to encourage people to build bigger and more houses because the construction industry had stagnated. With the financial culture of the Reagan-era — the 1980s culture of excess and consumption and big hair and what not — we started to see a kind of expansiveness of neoliberal policy on the financial sector.

With architecture culture, there was postmodernism. It was an indication of disconnected and ironically composed buildings made of different architectural elements from the past. Disney World architecture, essentially. Cartoonish buildings from architects like Michael Graves, Robert Stern, Robert Venturi. It was the last time that a movement that had happened in big architecture trickled down to developers and commercial architecture. Malls are very postmodern. It’s weird because there’s no political skepticism of postmodernism, which I feel is timely. That idea that popular is whatever is being bought is kind of a strange idea.

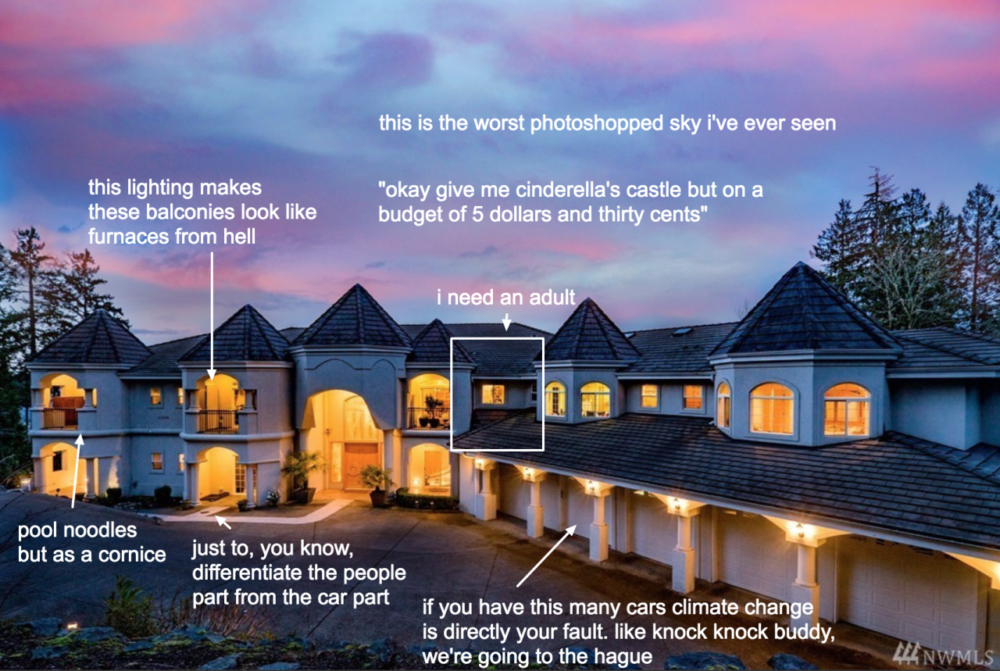

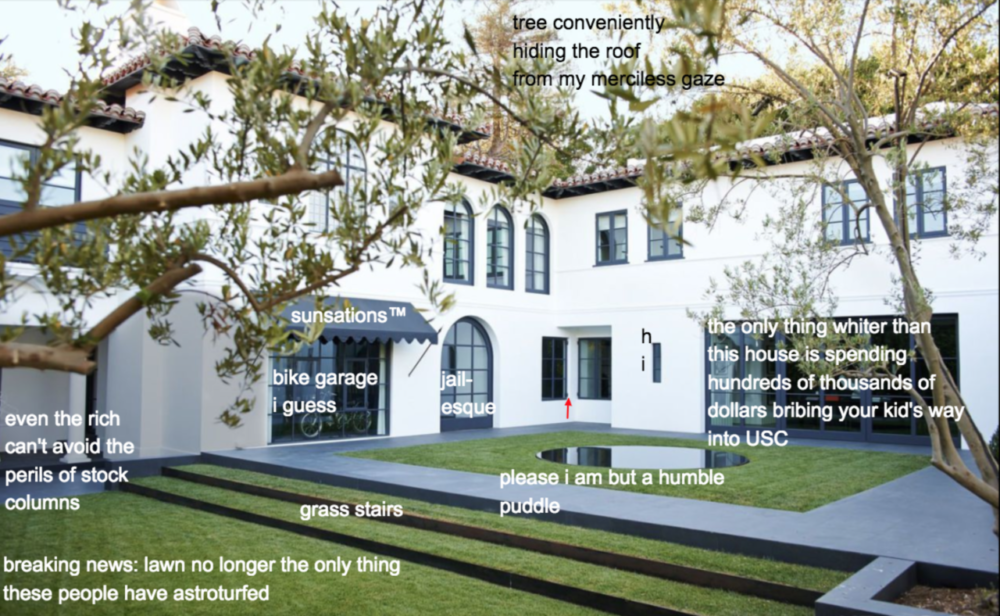

A McMansion Hell post featuring the “Spanish Colonial” house of Lori Loughlin and Massimo Giannulli, who “paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to secure their Instagram influencer daughter a spot at USC.”

NECHAMKIN: Do you think there’s a parallel phenomenon happening in cities?

WAGNER: Those big empty apartments in Hudson Yards that cost billions of dollars for millionaires to own are McMansions in the sky. Honestly, I hate Hudson Yards. It’s just stupid looking. It’s like a bunch of dildos in the sky. The architecture may change and the urbanism may be different, but the idea of projecting wealth is the same. It’s all about the value of the property or how much it’s worth. Everything in New York now is a Chase bank or a Starbucks.

NECHAMKIN: It was hard to find a place to meet for this interview around Union Square that wasn’t a chain.

WAGNER: Now there’s a Nutella store. What the fuck are you going to sell in there besides Nutella? You’ve spent all that money on Manhattan real-estate to sell hazelnut spread?

NECHAMKIN: Every store in New York is starting to look the same. It feels like the urban version of the mass HGTV-ification of the home is a push towards another extreme: stark minimalism.

WAGNER: All white, Instagram-tile floors, brass lamps. It’s weirdly Scandinavian but also very American in that there’s something very clinical about it. I’ve been to Scandinavia, and there’s a warmth to the places there that these omit. It doesn’t feel so prescribed. I think the trend has something to do with asceticism from post-recession life — this idea of having nothing. It’s weird because a couple of years ago everyone was talking about maximalism. They’d have velvet curtains and huge Turkish rugs and weird Moroccan crafts in their house. I’m here for it. All those houses look like the interior of your dream college professor’s house. Now, everything is white and there’s three succulents in a room. It’s definitely an urban thing, but on HGTV too, color is verboten in a way that is really sad. It used to be taupe. Gray was too depressing. Now, everything is gray.

NECHAMKIN: Though if everything comes back again, do you think there will be a shift, a new level of interest in this ironic, yet uncynical, aesthetic return to the early-aughts? Leaning into the tacky?

WAGNER: It’s just like what happened five years ago with the nineties. Every generation gets buying power at a certain age, and they’re drawn to things they remember from childhood. For me, it was a traumatizing time because I was in middle school, and my parents couldn’t afford Abercrombie & Fitch, so I got bullied. I always feel like that era embodied the worst of American consumption culture. It was the Hummer-era. Literally like, I’m rich fuck you.

NECHAMKIN: You have Lindsay Lohan and The Hills back on TV.

WAGNER: It was so superficial. To bring it back is just absurd. We have a relationship with this idea of a really dark future and, in 2006, everyone was like, I’m just going to keep getting richer, and nothing bad is going to happen. It’s a complete abandonment of the forward-thinkingness we’re moving toward.

NECHAMKIN: It almost feels like we’ve given up because we’ve hit rock bottom. Where is there to go now, except to the past, where things also sucked?

WAGNER: Trump is the embodiment of that 2006 culture because it was kind of like the reiteration of the 1980s — excessive personal consumption, having big drapes, giant bathtubs, and gold toilets. There’s almost an uninterrupted blur from the 1980s all the way through to the recession — the same aesthetics and the same ideas of what are meant to have made it. Trump is the McMansion of people.