required reading

Jonathan Franzen Is Battle-Ready for the End of the World

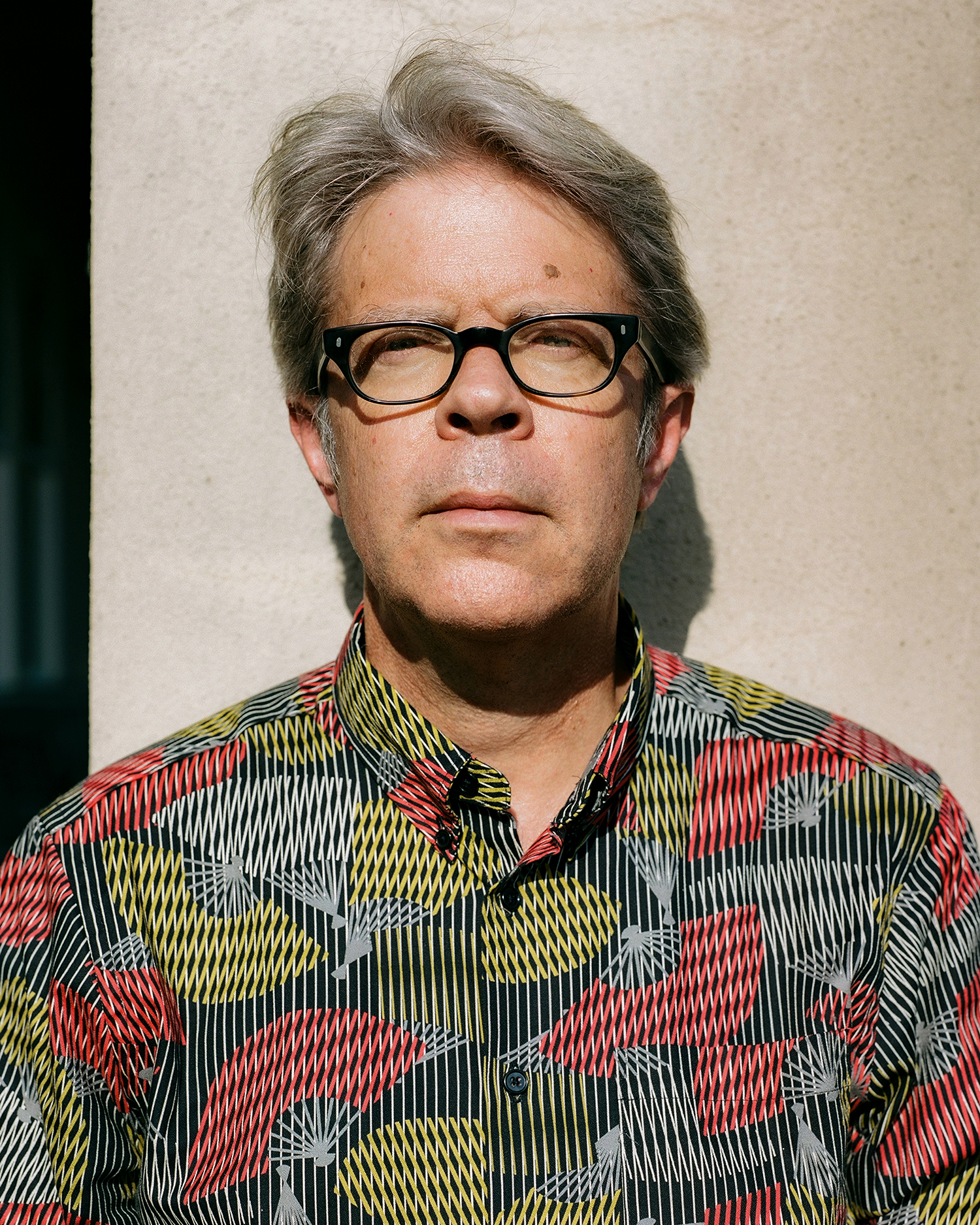

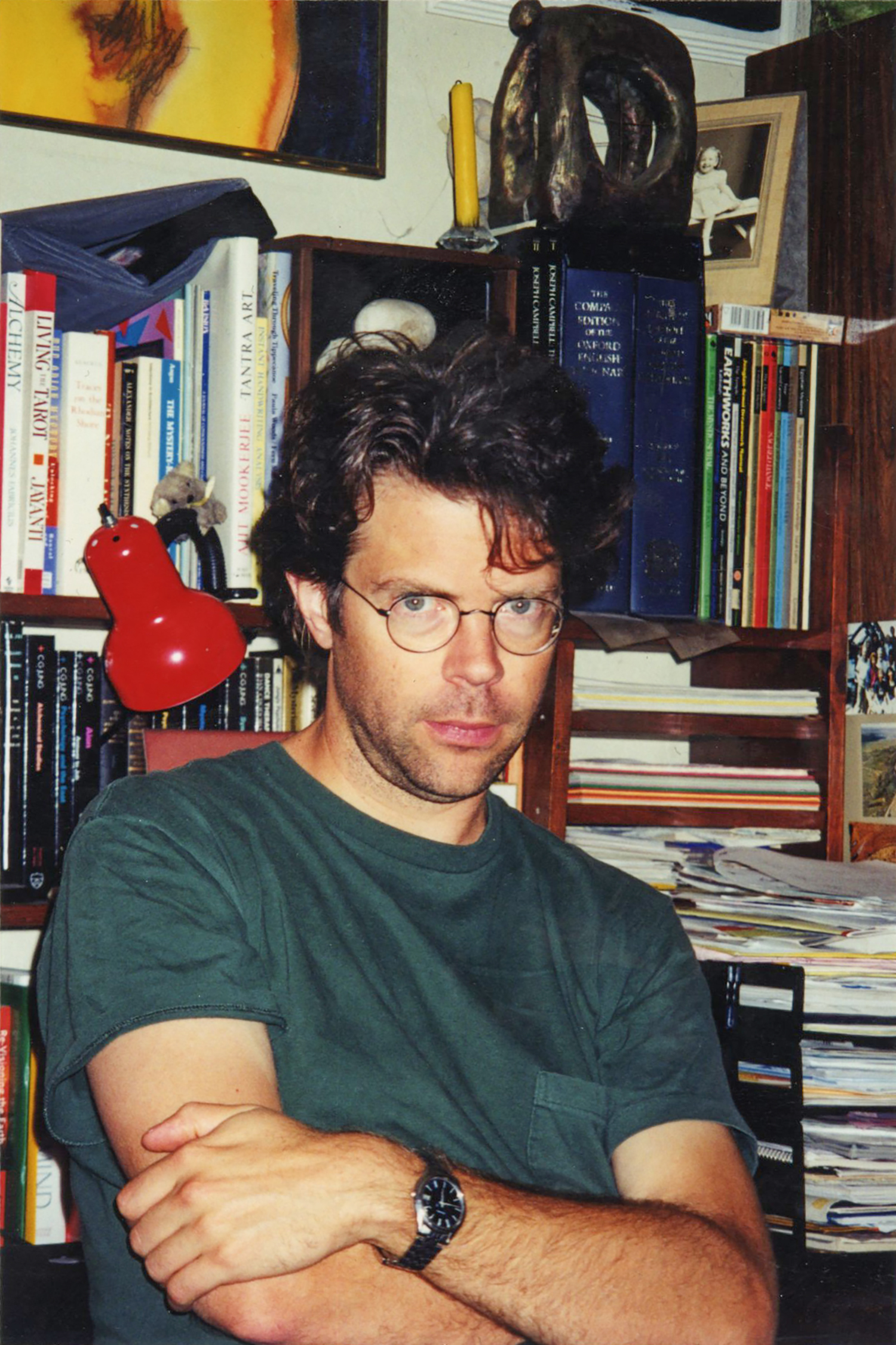

“I grew up in the middle of the country in the middle of the golden age of the American middle class,” Jonathan Franzen wrote in a 2006 autobiographical essay. While so much cultural pioneering of this new century has been centered on expanding the borders and peripheries of what constitutes the national character, the 62-year-old writer who was born in Illinois and grew up in the suburbs of St. Louis—a writer who excels in capturing that vivid, queasy American middle from which he hails—arguably remains the most vital fiction writer of our times. Franzen’s third novel, 2001’s The Corrections, has become the cornerstone of literary wit and style. Since that book catapulted him to fame, Franzen has continued to chart the wry, delirious struggle of American fulfillment in a series of brilliant, broad-canvas novels, while regularly delivering essayistic dispatches on various obsessions (birdwatching, German modernist novelists, ecological Armageddon).

In 2018, he moved from New York City to Santa Cruz, California. Over the years, there have been occasional rumors that Franzen had decided to stop writing novels. Thankfully, he has instead been hard at work on his current masterpiece, the first volume in a trilogy that spans three generations. This fall’s Crossroads delves into the emotional, spiritual, and material lives of the Hildebrandt family in early-’70s suburban Illinois. It is, without a doubt—sentence after glorious, unbridled sentence—an epic of the heart and mind. It brims with so much Franzenean energy and detail that I predict a slew of dissertations by the century’s end on Franzen’s descriptions of weather. And yet turning the pages, you can feel the scorch on your fingertips of each character burning with wants and desires and demons, in their pursuit of those mythic American values of gratification and goodness. Franzen has long been a friend and fan of the novelist, television writer, and playwright Theresa Rebeck. They met through Franzen’s “spouse-equivalent,” the writer Kathryn Chetkovich, and share, according to Franzen, “a feminist sensibility and a love of 19th-century novels.” Plus, when Franzen and Chetkovich were moving out of their Upper East Side apartment, Rebeck’s son, a newcomer to New York, was the lucky beneficiary of their leftover furniture. Here, Franzen and Rebeck discuss the meaning and madness of literature in an all but hopeless world. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

THERESA REBECK: I’m so glad to do this. It makes me feel like, “Oh, yeah, I’m not dead.” Just because we’ve all been so isolated, especially those of us who work in the theater.

JONATHAN FRANZEN: I live with a theater person, so I’m well aware.

REBECK: It’s been a psychic horror show not knowing what’s going to happen. But this will cheer me up. Before we talk about your novel, I wanted to ask about your essays. Do you see yourself as an essayist? Is part of your journey as a writer to lay out commentary as an observer of our culture?

FRANZEN: Not initially. I just wanted to be a novelist. And I really took to heart, “Show, don’t tell.” I thought it was a betrayal of the novel to actually say what I meant. But I am a person with opinions, and I do pay attention to the contemporary world. In hindsight, there was a deformingly large amount of stuff in my second novel, Strong Motion, that was more essayistic, more opinion-based, than purely about the characters. When I somewhat unexpectedly began writing essays for The New Yorker, which I did largely to make money, because I had zero money in the ’90s, it quickly revealed itself to be a way to take the pressure off the novels. It became an outlet for my opinions and for a certain analytical intelligence that will only take you so far in fiction.

REBECK: I see your essayistic voice in Crossroads, in the extraordinary flights of questioning, and in your positing intellectual and spiritual possibilities, which aren’t usually addressed in fiction.

FRANZEN: Except the difference there is that I don’t have a dog in that fight. I’m just trying to represent what a character might be trying to figure out. Whereas, in nonfiction, I really do back a dog. I get angry about something. I feel something is not being properly understood or talked about in the culture at large, and I want to correct that. It’s not like I check my intelligence at the door when I start writing a novel. It’s just that the valence is different.

REBECK: It’s not just cultural observations that you touch upon. Last night I read your beautiful essay about Edith Wharton. Are there other writers out there that you’d like to write about?

FRANZEN: One motive behind an essay is a sense of grievance. Throughout my career, I’ve had a grievance with the neglect of great women writers, ones who aren’t canonical. I’ve written about Alice Munro, and about Christina Stead. And Wharton, too. Even though Wharton has a great academic rep, I still didn’t think she was being given her due. In the master narrative of American literature, she’s this absolutely key figure. Fitzgerald gets most of the attention, but Fitzgerald came out of Wharton, especially The Custom of the Country. I’m such a lazy person—even with writing novels, I feel it’s more of a compulsion than any particular testament to my work ethic—and so, to actually write about a figure, I have to feel that the figure is misunderstood or underappreciated.

REBECK: If Fitzgerald comes out of Wharton, who do you come out of?

FRANZEN: I came out of the German moderns, because that’s what I studied in college. I was totally taken with Kafka and Rilke but also Thomas Mann, somewhat grudgingly, and Karl Kraus. I ended up being more of a Mann-like writer in spite of myself. What else do I come out of? Gosh, children’s books, the sci-fi I read as a teenager. Who knows?

REBECK: I love that there’s an influence of sci-fi in there.

FRANZEN: But all the novels I read as a young person, even the sci-fi, were realist in their conventions. They relied on techniques that began in the 18th century and really became an art form in the 19th century, beginning with Balzac and Austen. Then I encountered modernism. I have a naturally synthetic personality. I like to resolve differences, or at least keep two sides of an argument present at the same time. So, in my own mind, I feel like a fundamentally 19th-century writer whose life was changed by modernism.

REBECK: What are the three novels that you’ve read the most?

FRANZEN: Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and, probably the most, Harriet the Spy.

REBECK: I’ve read Harriet the Spy so many times! How many times are we talking?

FRANZEN: Eight.

REBECK: How many times have you read Middlemarch?

FRANZEN: Twice.

REBECK: I ask because you and I have had an argument about Middlemarch in the past. But we don’t have to revisit that.

FRANZEN: It’s a fine novel, Theresa.

REBECK: I have a few bird questions and there’s no one else I can ask. First, when did you become fascinated by birds?

FRANZEN: About 20 years ago. I came late to it. The only thing I didn’t come late to was writing novels. I came late to tennis, so I missed half a life—the way more athletic half of my life, But, yeah, I didn’t get to misspend my teens, twenties, and thirties as a birder. It only started in my forties.

REBECK: Are you one of those people who makes lists of all the birds you’ve seen?

FRANZEN: Oh my god, yes.

REBECK: How many birds have you seen?

FRANZEN: About 4,800 species, globally. I’m hoping at some point in my life to get to half the world’s bird species, and there are about 11,000 of them, so I’m getting there.

REBECK: You wrote very beautifully about seeing the emperor penguin and the king penguins. Is there another bird that was a very exciting experience for you?

FRANZEN: Kathy gives me a hard time about my penchant for saying, “This is my favorite bird.” She says, “You have 600 favorite birds.” And it’s true. Bird species are like people. Each of them has a very distinct personality and a distinct set of behaviors. And as much as I love one as I’m looking at it, then I go and I meet the next species. You don’t just love one person.

REBECK: Do you obsessively watch bird videos on Netflix or Instagram?

FRANZEN: No.

REBECK: I do. They’re so great.

FRANZEN: People email me so many links, they’re a plague.

REBECK: I’ve seen some really beautiful birds on there. There’s one—well, I’m not going to send it to you, but it changed my life, watching this little bird. You once told me that you like more humble birds. But I really like the crazy, vivid, nutty birds like the ones in New Guinea.

FRANZEN: You just sent me your new play, and I’m thinking, I’m the novelist who loves the quiet little brown birds. Your characters are the loud birds with the over-the-top plumage.

REBECK: Well, sometimes, for the stage, you’ve got to be a little louder. Let’s get to Crossroads, which is a large novel in its own right, and yet is the first of three parts, right?

FRANZEN: Theoretically, yes.

REBECK: How do you begin a task like that? Do you wander around with people talking to you inside your head? What do you do?

FRANZEN: I began by thinking I was writing one book, and it just turned into something larger. But where does a book come from? My novels all come from things in a drawer. My first novel, The Twenty-Seventh City, came from a thing I had in the drawer, a ten-minute scene I’d written in a playwriting workshop in college, which was the only writing workshop I ever took. Did you know that I started out intending to be a playwright?

REBECK: No. All I can say is you made a wise choice. It’s rough being a playwright.

FRANZEN: I know. I live with one. I knew the roughness even before the pandemic. But my first published work was a short play that I wrote with a friend in high school. For the workshop we had to bring in ten pages every week. You’re 19 years old, so how many amazing things do you have to write a play about? I ended up using something which itself was from a drawer—I took some characters from a play I’d written with two friends the summer before. It was a ridiculous play set in 19th-century India, making fun of the British colonialists. I took a couple of the Indian characters and put them in the kitchen of my parents’ house and had them interact with somebody like my father. Then, later, when I looked in the drawer, I thought, “Hey, you know what? There’s a novel in that.” The thing is, as you try to get novels going, there are a lot of false starts. You try ideas, they don’t work, and they end up in the drawer. But then, when you’re writing the next novel, you say, “Hey, didn’t that thing have five good pages?” And that was the case with Crossroads. I don’t mind telling you this, but I thought I might write a movie screenplay. I had a rom-com idea. It was about a Republican operative who tries to swing an election in Montana in favor of the Republican candidate by funneling money to a Green Party candidate. And of course, he gets involved with this lefty woman, and he can’t tell her what he’s really doing. Cool idea for a rom-com, right? But then I got fed up with the film business and thought, “Why am I writing a film that probably won’t get made? Why don’t I make a novel out of this?” So I wrote 60 pages, and it totally didn’t work. I mean, it was plausible. I can make someone think I’ve got something going, but I knew I didn’t have anything going. So that went into a drawer. Then some time went by, and I met a guy. I won’t say who, I won’t say where, but I met a guy and I thought, “Now that is a novel character.” And so I started to figure out how to put that character in a novel with the 60 pages I had in a drawer. How to create a narrative superstructure that could encompass these very different elements. And then, in terms of Crossroads, there was supposed to be an overture set in the early ’70s. I started writing and realized I’d never written fiction about the ’70s, never written about my experience of religion growing up, and I realized, hey, there’s more than an overture’s worth here.

REBECK: So you make a lot of your decisions when you’re already far down the road.

FRANZEN: I don’t want to read a novel that feels like it’s written from an outline. It’s better to set yourself almost insoluble problems. Like, I want my characters to get to a certain place, and it’s really hard to imagine them going there. So how do I get them there? If it’s an adventure for the writer, it’s going to be an adventure for the reader.

REBECK: I feel like this book is deeply, deeply Midwestern. When you decided to write about your youth and your own experiences with faith, did it feel like it was inevitable that the Midwest would claim it? Because I’m from Ohio and—

FRANZEN: Who would have guessed?

REBECK: Why do you say that?

FRANZEN: It’s all over your work.

REBECK: I do feel that there’s something different about the Midwestern consciousness than, say, the East Coast consciousness. Do you think that equates to a cultural difference?

FRANZEN: I was once challenged by a BBC interviewer to name what was uniquely Midwestern about the Midwest. Everything I would mention, he would say, “But isn’t that also the South? Isn’t that California? What you’re describing could be the north of England.” And I realized afterward that he was right. I think the Midwest is a myth. And, like all myths, it serves its purpose. People like to think there’s something distinctive about the Midwest, but I lived in New York for 25 years, and what is New York full of? Midwesterners. So what does that mean the Midwest is full of? It’s full of potential New Yorkers. I was the kind of Midwesterner who was not going to let other people shove their way onto the subway ahead of me, in spite of being raised as a nice Midwestern boy. Which is probably why I ended up in New York—because nice boys have to wait for the next train. The Midwest is attractive to me for the simple reason that it’s where I spent my childhood. I know what it smells like. I know what the weather is like. I know what the streets look like. I know what the conventions of social behavior are. And the novels that really work for me are ones set in a place that feels like a home. My favorite example is the amazing long stretch of War and Peace that’s set at the Rostovas’ country house in the winter. Apart from Natasha being in some trouble regarding Prince Andrei, not much is going on. There’s a whole lot of, “Now we’re going to go hunting. Now we’re going to go out in the sleigh.” It’s probably my favorite passage in all of fiction. Nothing much is happening, but you feel like you just want to stay there. Even though I’ve never been to Russia, it feels like home. So when I’m working on a novel, I’m looking for a location, a mise-en-scène, that I want to spend time with. It’s not that I have any particular love for the Midwest. I hardly ever go back to the Midwest. It’s that I know how to do it.

REBECK: Your work always feels like it’s got a psychological and a scenic vividness. I wonder if you think about seeing a version of it onscreen? I’ve had my own struggles with Hollywood, but do you speculate about that kind of future for your work?

FRANZEN: I have a perfect record of failing to put my novels on the screen. I’m rather proud of that record at this point. Serious efforts were made with The Corrections, even more seriously with Purity, and a very fine showrunner is at work on Freedom as we speak. I wish her great success, and yet part of me will be proud if she and the production company fail, because, goddamnit, there should be a place for novels, too. Not everything has to go on the screen. That said, I started out as a playwright, and my experience in writing for television, which I did with both The Corrections and Purity, brought me back to the simple question: What does the character want? In every scene, characters should want things, and ideally, what the various characters want should not be the same.

REBECK: That’s always better.

FRANZEN: It’s always better, right? I feel very at home in television, in part because it’s so much like the serialized novels of the 19th century, but my allegiance is to the printed word.

REBECK: I was very taken with your essay about going to Antarctica. In fact, I was reading part of it to my husband, and he told me I had to stop because he wanted to read the whole thing himself. But the thing that was remarkable to me was that you decided before you went that you weren’t going to take any pictures, because pictures inevitably disappoint, and that’s because they have a frame and there are things that are left out of the frame. And what is beyond the frame is also an enormously important part of the story. I was thinking, that’s what fiction does. It fills in more. I sometimes wonder what happens when we translate the written word to the screen.

FRANZEN: What’s outside the frame in fiction is what the reader brings. As big as the canvas of the screen is visually, it’s not as big and potentially not as rich as the screen of what the reader might imagine. This is what I’m going to say against film in favor of fiction: When I’m reading, the writer is inside my head in a way that a more superficial medium simply cannot achieve. What you do get in a good TV production or a good film is what the actors bring. Some of the work being done by a reader can be done by great actors. The part of me that would love to see something of mine get made is the part that would love to see what actors would do with these lines.

REBECK: I do think what struck me most about Crossroads that I haven’t found in a lot of contemporary fiction is the puzzling over spiritual and moral questions. Was that your intention when you started on the three-part series?

FRANZEN: The overarching series title is “A Key to All Mythologies.” It’s a joke title. And yet I have, at this point in my life, a broad concern for the stories that people tell themselves to keep on living. The novel starts in the early ’70s, when it was still not politically unacceptable to call yourself a Christian. In the ’80s, basically, liberal Christianity began to die. But it was still very much alive in the ’70s. So it made sense to put that particular mythology front and center in the first book. I think all of my characters, throughout my career, have been concerned with what it means to be a good person. “How to live?” is kind of a drumbeat in my work, so I don’t think that’s particularly new. What may have changed is that I’m no longer inclined to make fun of my characters. And it seemed particularly important, given that there’s a backdrop of Christian faith for many of these characters, to simply inhabit their spiritual struggle, rather than commenting on it or having it mean something larger than what it is for that one person. To just be there with the person—that was the endeavor.

REBECK: In your book of essays, you mention that you see the end of the world coming. I think we’ve arrived at it. Do you feel like the end of the world is happening right now?

FRANZEN: Yeah, it’s happening in slow motion, of course. It’s not alien spaceships arriving and obliterating us with powerful energy beams. It’s not a comet hitting the earth. It’s not—so far at least—nuclear Armageddon. It’s a slippage, an escalating series of shocks. And we’re starting to see some of those shocks. It’s not like you’ll be able to point your finger and say, “This is where the world ended.” It’s not even clear that the world will “end.” It’s that something radically different has begun to occur. And it’s driven, in the broad scheme, by the carbon in the atmosphere.

REBECK: I’m going to ask an impossible question. How do you continue to be a moral person while the world is changing so radically?

FRANZEN: I think kindness is an almost transcendent value and one that seems to have been substantially lost in the world of social media. Kindness and everything that kindness entails—listening, respecting, being polite, recognizing other people as other people, rather than as projections of yourself. Will it save the world? Probably not. The world is always in danger of ending. But given that the larger situation of the world is essentially hopeless, it’s important to look for hope in other places. I think hope and kindness are almost always found in the same place. When someone is kind, it gives me hope. And when I have hope, I’m able to be kind. That was a profound although possibly erroneous statement.