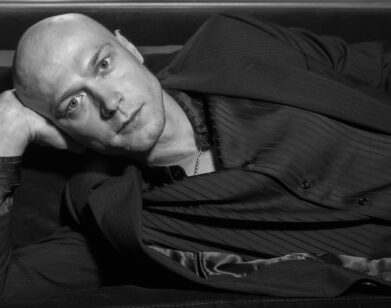

Johnny Flynn

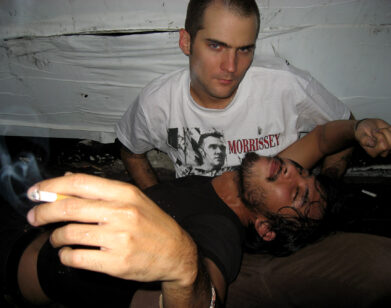

JOHNNY FLYNN AT UNTITLED MOTORCYCLES IN LONDON, APRIL 2017. PHOTOS: IAKOVOS KALAITZAKIS. STLYING: MARIANNA FRANNAIS. GROOMING: LEE MACHIN FOR CAREN AGENCY. STYLING ASSISTANTS: PAULA SZUMINSKA AND HELANA LUKO.

A popular myth exists about Albert Einstein: before he became one of the most celebrated intellectuals in the world, the German-born physicist was a poor student. It’s not entirely true—he always excelled in his preferred subjects—but elements of it are. Ron Howard‘s Genius, a new National Geographic miniseries, explores some of Einstein’s contradictions. Following Einstein’s professional and personal evolution from his youth in Munich to his early interactions with the Nazi party in the 1930s, the series shows him failing his entrance examination to Zurich Polytechnic as a teenager, and philandering with his secretary as a celebrated professor. At the height of his fame, Einstein is played by Geoffrey Rush; as a young man, he is played by British actor and musician Johnny Flynn.

Though Flynn is perhaps better known as a musician—on Monday, he released his fourth album, Sillion, via Transgressive Records—he always intended to become an actor. After leaving school at 18, he studied acting at Webber Douglas alongside Paul Anderson, Rupert Friend, and Tom Mison. In recent years, the 34-year-old has acted onstage at the Royal Court (in Bruce Norris’s The Low Road, 2013, and Martin McDonagh’s Hangman, 2015), on screen in indie films such as Olivier Assayas‘s Clouds of Sils Maria, and on television in the Netflix comedy series Lovesick (formerly Scrotal Recall), which has been renewed for a third season.

EMMA BROWN: How did you get involved with Genius? Was it a pretty normal process—your agent sends you an email?

JOHNNY FLYNN: I got an email detailing the project and it struck me as almost comically good—a series about Einstein being piloted by Ron Howard and produced by his company. I didn’t put myself on tape. I thought it was too good. I sometimes self-edit when it comes to auditions and go, “They’re not going to cast me so I’m not going to do it.” It just seemed unfeasible that anyone could turn me into Albert Einstein. So I missed the deadline. Then I told my friend that I was doing this other series with in Glasgow, and she was like, “You idiot. You have to do it.” Luckily, they still hadn’t found someone for the part, and the next thing I knew I was talking to Ron on Skype. What really got me excited was hearing his impressions of Einstein. He was quite humble in his approach; he didn’t have very set answers to who this guy was. He wanted to go on the exploration with the actor and ask these questions together. I went in and did a screen test, but I know from hearing their stories that they were wondering how they could turn me into Einstein. They talked to some makeup designers and they seemed confident. I had to wear various prosthetic pieces and dye my hair and wear contact lenses and stuff like that. I think until I saw it all together, I didn’t really believe that it could be done. I feel very lucky that they believed I could do it.

BROWN: To be fair, I have no idea what young Einstein looked like. I only have an image of older Einstein.

FLYNN: Yeah, there’s some grace in that. That’s the whole thing with the show, [it’s] a challenge to find out who the young guy was, not just the wild-haired professor that we think of. When I started looking at pictures and reading accounts of him as a young man, I realized he was not at all what I’d imagined. He was kind of rakish and incredibly charming and might have come across as slightly arrogant or aloof, but I think it was a confidence in his ideas. When he was in his early 20s, people hadn’t really listened to him yet, so he was kind of this unproven genius with what were then pretty outlandish ideas about space and time and light, and these big principles of the universe.

BROWN: I was really intrigued by his relationship with Marie in the first episode. They seemed like such a nice couple and then he just left her.

FLYNN: Well, yeah. He did things that, unfortunately, a lot of young people—young men, especially—do. He behaved badly at times. But in his defense, if you compare it to the way relationships work nowadays, you wouldn’t necessarily expect to stay with the person you met when you were 17. You’d have your first love and that would maybe fall apart when you went off to college, and that’s kind of what happened with him. What’s interesting is he was discovering that the universe wasn’t absolute in terms of time and space, and he was maybe applying some of that non-absoluteness to his personal relationships, which had slightly unfortunate consequences.

BROWN: Did you interact with Geoffrey Rush at all and discuss the character? Or were you completely separate because you didn’t share any scenes?

FLYNN: We were very collaborative, actually. We were introduced by Ron on email, and then we spoke on Skype a lot. There was a time when he was in London early on in the process before he’d started filming, and I hadn’t done very much, and we did a load of physical workshops together—exercises where we walked around in a circle trying to match each other’s gait. Then we interviewed each other as young to old, and we had the same dialect coach, who was very good at working with us on rhythm. Then we took over. [Geoffrey] had done this before—he’d shared a character with another actor—in that film Shine [1996], which he was so incredible in. He shared some of the things that they’d done that had worked, and he was very generous and open-hearted with his process. We watched each other do scenes and a huge part of it for me was hooking up with him.

BROWN: What is Ron Howard like as a director? Does he give you lots of notes?

FLYNN: He’s very particular, but I think he’s very sensitive to actors because he was an actor. He would see what my impulse was and what I was doing, and he would build on that. He’s really fantastic collaborator. Obviously he’s incredibly experienced and has a great vision for how things can work. There were shots on the day where I kind of thought, “I have no idea how they can use this,” or, “I haven’t done anything like this before,” and then I’d see it in the final cut and it’s an invaluable part of the storytelling in lens that you wouldn’t think to get. I was so impressed by him. He’s a very humble, sweet guy. We’ve just been hanging out at SXSW.

BROWN: I know that you’re a musician as well as an actor. Does one come before the other?

FLYNN: It depends on what I’ve been doing less of. The thing I’ve been doing less of is always the thing I’m striving for to redress the balance. I really need them both as creative outlets. It’s great being an actor and being part of a play or a film where there’s usually quite a big group of people who are collaborating, and your job is really to fit in and share that energy. With music, because I write the songs, it’s a broader, more abstract process. Touring with my band is a big part of what I’ve been doing the last 10 or 12 years, and that’s band of brothers and sisters—literally, my sister is in the band. They’re both integral parts of my existence.

I’ve always identified as an actor. That’s what I set out to do. My father was an actor, both of my older brothers are actors, my younger sister is an actress. For me, that’s my job, that’s my craft. But then all through school and through drama school, I was gigging and running nights and playing in bands and I just didn’t want to let that go. It’s been a good retreat when things haven’t worked out or haven’t been as flowing in the acting business. Sometimes you feel like there’s only a certain type of part available to you, or you just get fed up of being thrown against a wall and doing the whole audition thing. For me, it’s great to know that there’s this other thing that I can bury myself in and feel free. Especially for actresses, I think, it’s really hard being a young actor. There are a lot of people investing in what you look like and how you are and how you behave. It can get pretty grim. When I was young and unable to dictate how I wanted to do things, being able to retreat into music was a really good thing for me.

BROWN: Do you feel like you grew up in an acting world? Did you ever go to set when you were little?

FLYNN: I did a little bit. My dad was an actor, but he was out of work quite a lot when I was a kid. Things were quite dry. So I felt like he was always around, and we had this pretty idyllic life living in the country. I wasn’t so familiar with being on set, but the times that I did go, or when I went backstage when he was doing a play, what I got from it was this magical world of storytelling. It was very alluring, this thing of being behind the curtain—not in the audience, but where the story was told from. I immediately got a sense of, “This is what I want to do.” Especially with the stage stuff, I got a huge thrill from that, and I’m still addicted to that sense of walking through the stage door of a theater.

BROWN: Were your parents happy when you told them you wanted to be an actor?

FLYNN: My dad really tried to stop me. He wasn’t happy at all. I think because it had been pretty touch-and-go with paying our rent when I was a kid, we really didn’t have any money. He died when I was 18, so just as I was leaving school and launching into adult life, I turned around and said I was going to be an actor and was applying for drama school. He was like, head-in-hands, because he was going to leave soon and he didn’t want to feel like I was going to be in any trouble. But you just can’t stop a kid from following their heart. I got my place at drama school just before he died, and I think he was okay with that. He wrote me a letter—because I got a place at a university to do English as well, and he would’ve preferred that. He made that known. He was also a bit dismissive of the drama school I was going to. He was like, “If you’re really serious about it, you’ll get into RADA,” which is where he went. But I was really happy at Webber Douglas. He didn’t know what he was talking about, really.

BROWN: Well, Webber Douglas is bit grittier in style, right?

FLYNN: It was more real. RADA’s obviously great, and I’ve got a lot of friends that went to the college, but Webber Douglas, they didn’t have fancy facilities, there weren’t hundreds of classrooms. We were rehearsing in church halls and running around this area of London where the school was spread out amongst all these civic buildings and churches. The teachers were free to teach whatever course they had developed over the years and they were all these really interesting characters. I think I just got a much better training there than I would’ve anywhere else. It was made up of individuals, and they weren’t trying to wipe people clean and start from scratch. It wasn’t like boot camp in that way. It was celebrating individuality, which is nice. A lot of great comedians and comic actors have come out of there. There was a great physical theater side of the course and amazing movement teacher. I loved it.

BROWN: One of the actors I really like who went to Webber Douglas is Paul Anderson, who’s in Peaky Blinders.

FLYNN: He’s a very good friend of mine. He graduated at the same time as me. He’s a character. I did a play last year and I actually based my character on him. He came to see it and we had this night out and I was telling him that I based it on him. I think he was pleased…

BROWN: He’s definitely done that to other people. When we did a piece on him he said his voice in Legend was based on a friend’s, so he can’t complain.

FLYNN: My voice in this play was literally a rip-off of him, so that’s good. It comes around.

BROWN: You mentioned earlier that you started playing music while you were at school.

FLYNN: I was a music scholar at school. I studied violin and trumpet, and I sang in the choirs. I had to do it, which is almost why I wanted to be an actor—when they were doing school plays, I couldn’t go to rehearsals because I had to do orchestra practice. By the time I was 18, I was really gunning for it.

BROWN: Do you still play the violin and trumpet often? I know you play the guitar as well.

FLYNN: Yeah, a little bit. I got to play the violin in Genius. I play some cool Bach Partitas. Most of the violin playing I do now, I play on my own songs, but I’ve also scored some TV and films, which is usually me just noodling and layering things up. It’s not like Bach or Mozart, but that’s what I studied, so I had a few lessons with a guy out in Prague where we were filming and I dusted off the Bach. I’m thrilled to have restarted it. My way into playing in bands when I was at college was through the violin. I’d be the token violin player.

GENIUS AIRS TUESDAY NIGHTS ON NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC. SILLION (TRANSGRESSIVE) IS OUT NOW.